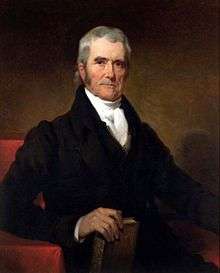

William Cushing

| William Cushing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

In office September 27, 1789 – September 13, 1810 | |

| Nominated by | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Story |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

March 1, 1732 Scituate, Massachusetts Bay, British America |

| Died |

September 13, 1810 (aged 78) Scituate, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Religion | Unitarianism |

| Signature |

|

William Cushing (March 1, 1732 – September 13, 1810) was one of the original six Associate Justices of the United States Supreme Court, from its inception to his death. He was the longest-serving of the Court's original members, sitting on the bench for 21 years. Had he accepted George Washington's appointment, he would have become the third Chief Justice of the United States. He was also the last judge in the United States to wear a full wig (Court dress).[1][2]

Early life and education

Cushing was born in Scituate, Massachusetts, on March 1, 1732. The Cushing family had a long history in the area, settling Hingham in 1638. Cushing's father John Cushing (1695-1778) was a provincial magistrate who in 1747 became an associate justice of the Superior Court of Judicature, the province's high court. William Cushing's grandfather John Cushing (1662-1737/38) was also a superior court judge and member of the governor's council.[3]

Cushing's mother, Mary Cotton Cushing, was a daughter of Josiah Cotton (1679/80-1756). They were descended from Rev. John Cotton, the great 17th century Puritan theologian. Josiah Cotton and Richard Fitzgerald, a teacher at a local Latin school, were responsible for young Cushing's early education.[4]

Cushing graduated from Harvard College in 1751 and became a member of the bar of Boston in 1755. After briefly practicing law in Scituate, he moved to Pownalborough (present-day Dresden, Maine, then part of Massachusetts), and became the first practicing attorney in the province's eastern district (as Maine was then known). In 1762 he was called to become a barrister, again the first in Maine. He practiced law until 1772, when he was appointed by Governor Thomas Hutchinson to replace his father (who had resigned) on the Superior Court bench.

Career

Not long after his tenure on the Massachusetts bench began, a controversy arose over revelations that court judges were to be paid by crown funds from London rather than by an appropriation of the provincial assembly. Cushing did not express any opinion on the matter, but declined the crown payment in preference to a provincial appropriation.

After the American Revolutionary War broke out in April 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress (which exercised de facto control over the province outside besieged Boston), sought to reorganize the courts to remove the trappings of British sovereignty. Consequently, it essentially dissolved the Superior Court and reformed it in November 1775. Of all its justices, Cushing was the only one retained.

The congress offered the seat of Chief Justice first to John Adams, but he never sat, and resigned the post in 1776. The provincial congress appointed Cushing to be the court's first sitting Chief Justice in 1777. He was a charter member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1780).[5] He would sit as Massachusetts Chief Justice until 1789, during which period the court ruled in 1783 that slavery was irreconcilable with the new state constitution, and it was ended in the state.

Massachusetts chief justice

In 1783, Cushing presided over a series of cases involving Quock Walker, a slave who filed a freedom suit based on the language of the new state constitution. In Commonwealth v. Jennison, Cushing stated the following principles, in his charge to the jury:

As to the doctrine of slavery and the right of Christians to hold Africans in perpetual servitude, and sell and treat them as we do our horses and cattle, that (it is true) has been heretofore countenanced by the Province Laws formerly, but nowhere is it expressly enacted or established. It has been a usage -- a usage which took its origin from the practice of some of the European nations, and the regulations of British government respecting the then Colonies, for the benefit of trade and wealth. But whatever sentiments have formerly prevailed in this particular or slid in upon us by the example of others, a different idea has taken place with the people of America, more favorable to the natural rights of mankind, and to that natural, innate desire of Liberty, with which Heaven (without regard to color, complexion, or shape of noses-features) has inspired all the human race. And upon this ground our Constitution of Government, by which the people of this Commonwealth have solemnly bound themselves, sets out with declaring that all men are born free and equal -- and that every subject is entitled to liberty, and to have it guarded by the laws, as well as life and property -- and in short is totally repugnant to the idea of being born slaves. This being the case, I think the idea of slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct and Constitution; and there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational creature, unless his liberty is forfeited by some criminal conduct or given up by personal consent or contract ...[6]

This was taken to mean that slavery was incompatible with the state constitution ratified in 1779, and that slavery was therefore ended in the state.[7][8] The case relied on a 1781 freedom suit brought by slave Elizabeth Freeman (Mum Bett), also known as Mum Bett, on the same grounds; a Massachusetts county court ruled in her favor in 1781.

During Shays' Rebellion (1786–87), Cushing ensured that court sessions continued, despite the aggressive protests of the armed rebels, and later presided over their trials. A year later, in 1788, he served as vice president of the Massachusetts convention, which narrowly ratified the United States Constitution.[9]

Supreme Court appointment

When George Washington became President of the United States, Cushing was among Washington's first choices for Supreme Court justices. He was nominated on September 24, 1789, and confirmed by the Senate two days later. Washington signed Cushing's commission on September 27. Although Cushing became Washington's longest serving Supreme Court appointment, only 19 of his decisions appear in the case reporters, mainly due to frequent travels and failing health, as well as the incompleteness of the case reports of the era. He generally held a nationalist view typically in line with the views of the Federalist Party, and often disagreed with Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans. His two most important decisions were probably Chisholm v. Georgia and Ware v. Hylton, which regarded intrastate suits and the supremacy of treaties.

Cushing administered the oath of office at Washington's second inauguration as president.

Nomination for Chief Justice

When John Jay resigned from the Court in 1795, Washington faced the task of appointing a new Chief Justice. Washington appointed John Rutledge on July 1, 1795 during a Senate recess, during which time Rutledge served by recess appointment. On December 15, 1795, during the Senate's next session, it rejected Rutledge's nomination.

Washington subsequently nominated Cushing on January 26, 1796; the Senate unanimously confirmed the nomination. An unverified story tells of a diplomatic dinner party the night of the Senate's confirmation vote, where Washington gave Cushing accolades as the Chief Justice of the United States, asking Cushing to sit in the seat to Washington's right, much to Cushing's surprise.[10] The following day, Washington signed and dispatched Cushing's commission.

Cushing received his commission on January 27, but returned it to Washington on February 2, declining appointment.[11] An error in the rough minutes of the Court on February 3 and 4, 1796 lists Cushing as Chief Justice, although this entry was later crossed out. This error can be explained by the text of the Judiciary Act of 1789,[12] which allowed for the Court to hear cases with a quorum of only four justices; that is, the Chief Justice need not always be present for the Court to conduct business. As Cushing was the most senior Associate Justice present on those dates, he would have been expected to serve as the presiding justice, directing the Court's business.

Washington then nominated Oliver Ellsworth to be Chief Justice, transmitting the nomination to the Senate in a March 3 message stating that Ellsworth would replace "William Cushing, resigned."[13] Subsequent histories of the Court have not counted Cushing as Chief Justice, but instead report that he declined the appointment. Had Cushing accepted promotion to Chief Justice and then resigned, he would have had to leave the court entirely; accepting the appointment would have implicitly required Cushing to resign his place as Associate Justice. That he continued on the Court as an Associate Justice for years afterward lends weight to the assertion that Cushing declined promotion. Additionally, Cushing's February 2 letter explicitly stated his return of the commission for Chief Justice, and his desire to retain his seat as Associate Justice.[11]

Later life and death

In 1810, Cushing died in his hometown of Scituate, Massachusetts. He is buried in a small cemetery there which is also a state park. His wife preferred that he be buried at the Norwell Congregational Church, but he insisted on being buried in Scituate.[14]

See also

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Ellsworth Court

Notes

- ↑ Flanders, Henry (1875). William Cushing. Oliver Ellsworth. John Marshall. J. Cockcroft. p. 37.

- ↑ Schwartz, Bernard. A History of the Supreme Court. Oxford University Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Perry, James R. (1985). The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800. Columbia University Press. p. 26.

- ↑ Cushman, Clare (Dec 11, 2012). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–2012. CQ Press. p. 9.

- ↑ "Charter of Incorporation of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ Harper, Douglass. Emancipation in Massachusetts (2003) Slavery in the North. Retrieved 2010-05-22

- ↑ "Massachusetts Constitution, Judicial Review, and Slavery - The Quock Walker Case". mass.gov. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- ↑ Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 114

- ↑ Michael Lariens, "William Cushing Biography".

- ↑ Flanders, Henry (1875). The Lives and Times of The Chief Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. 2. New York, NY: James Cockcroft. p. 46.

- 1 2 Marcus & Perry, pg. 103.

- ↑ 1 Stat. 73

- ↑ Marcus & Perry, pg. 120.

- ↑ William Cushing memorial at Find a Grave.

References

- Marcus, Maeva; Perry, James R., eds. (1985). The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800. 1. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Ross E. Davies: "William Cushing, Chief Justice of the United States", University of Toledo Law Review, Vol. 37, No. 3, Spring 2006

- Tony Mauro: "The Chief Justice Who Wasn't There", Legal Times (September 19, 2005)

- Rugg, Arthur (December 1920). "William Cushing". The Yale Law Journal (Vol. 30, No. 2). JSTOR 787099. (Rugg was chief justice of the Massachusetts SJC when he wrote this biographical sketch.)

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

- Michael Lariens, William Cushing Biography.

- Oyez, U.S. Supreme Court media, William Cushing Biography.

- Supreme Court Historical Society, William Cushing.

- William Cushing at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Peter Oliver |

Associate Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court of Judicature 1772–1777 |

Succeeded by David Sewall |

| Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court 1777–1789 |

Succeeded by Nathaniel Sargent | |

| New seat | Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1790–1810 |

Succeeded by Joseph Story |

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||