Where the Sidewalk Ends (film)

| Where the Sidewalk Ends | |

|---|---|

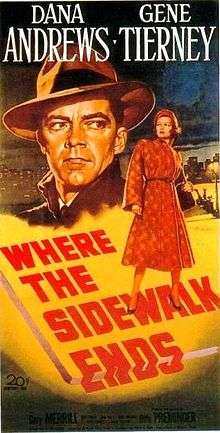

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Otto Preminger |

| Produced by | Otto Preminger |

| Screenplay by | Ben Hecht |

| Story by | |

| Based on |

Night Cry 1948 novel by William L. Stuart |

| Starring |

Dana Andrews Gene Tierney |

| Music by | Cyril Mockridge |

| Cinematography | Joseph LaShelle |

| Edited by | Louis Loeffler |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1 million[1] |

Where the Sidewalk Ends is a 1950 American film noir directed and produced by Otto Preminger.[2][3] The screenplay for the film was written by Ben Hecht, and adapted by Robert E. Kent, Frank P. Rosenberg, and Victor Trivas. The screenplay and adaptations were based on the novel Night Cry by William L. Stuart. The film stars Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney.

The film narrative concerns ruthless and cynical Mark Dixon (Dana Andrews), a metropolitan police detective, who despises all criminals because his father had been one. Considered a classic of the film noir genre, the brand of violence shown in the film, "lurking below urban society", is an important noir motif.[4]

Plot

New York City 16th Precinct Police Detective Dixon (Dana Andrews), who has been demoted by his superiors for his heavy-handed tactics, subjects murder suspect and gambler Ken Paine (Craig Stevens) to the third degree – he strikes the drunken Paine in self-defense and accidentally kills him. Paine, however, had a silver plate in his head, a fine war record, and newspaper friends. Dixon then dumps Paine's body in the river, and is later assigned to find his killer.

Dixon tries to place the blame on an old gangster enemy, Tommy Scalise (Gary Merrill), but inadvertently puts cab driver Jiggs Taylor (Tom Tully) under suspicion instead. Having fallen in love with Jiggs' daughter and Paine's estranged wife, Morgan Taylor-Paine (Gene Tierney), Dixon tries to clear the cabbie without implicating himself, but ultimately becomes tangled in a web of his own creation. The 16th Precinct commander and Dixon's boss, newly promoted Detective Lt. Thomas (Karl Malden), are convinced that Morgan's father is the killer.

Dixon continues to find a way to stop Jiggs from being found guilty of murdering Paine, and also tries to redeem himself. In an attempt to move the evidence away from Morgan's father and blame Scalise, Dixon comes face to face with the gangster and his cronies. A shoot-out leaves Dixon wounded, but the police arrive to arrest Scalise and his mob. Jiggs is finally cleared of the charges. At the end Dixon reassesses his life and decides to confess. He is satisfied that Morgan believes in him regardless of the outcome.

Cast

- Dana Andrews as Detective Sgt. Mark Dixon

- Gene Tierney as Morgan Taylor-Paine

- Gary Merrill as Tommy Scalise

- Bert Freed as Detective Sgt. Paul Klein (Dixon's partner)

- Tom Tully as Jiggs Taylor, Morgan's father

- Karl Malden as Detective Lt. Thomas

- Ruth Donnelly as Martha, owner of Martha's Cafe

- Craig Stevens as Ken Paine

Background

This is the last film that Otto Preminger would make as a director-for-hire for Twentieth Century Fox in the 1940s. The series includes Laura, which also stars Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews, Whirlpool, and Fallen Angel.[5]

Filming locations

The film was entirely shot in New York: New York City and Washington Heights, Manhattan.

Reception

Critical response

Most critics compare the film unfavorably to Preminger's earlier film Laura which used much of the same talent as this film. According to film writers, this film, a grittier noir, does succeed in showing a darker side of police similar to the film noirs that follow it.

The New York Times film critic, Bosley Crowther, while thinking the script was too far-fetched, liked the way the dialogue was written, and the acting as well. He wrote, "...the plausibility of the script by Ben Hecht, an old hand with station houses and sleazy underworldlings, is open to question on several counts. Not so, however, his pungent dialogue and unfolding of the plot, which Otto Preminger, who guided the same stars through Laura several seasons back, has taken to like a duck to water and kept clipping along crisply till the fadeout."[6]

The staff at Variety magazine praised the direction of the film. They wrote, "Otto Preminger, director, does an excellent job of pacing the story and of building sympathy for Andrews."[7]

Noir analysis

According to Boris Trbic, scriptwriter and media instructor, Where the Sidewalk Ends reflects a specific phase in the development of the film noir style. The large film production companies in the early 1950s backed away from the social-problem drama, and instead made "low-budget and low-risk thrillers" such as: Panic in the Streets, No Way Out, this film, and others. As such, they avoided the "wrath of conservative critics and social watchdogs."[8]

Preservation

The Academy Film Archive preserved Where the Sidewalk Ends in 2004.[9]

References

- ↑ Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century-Fox: A Corporate and Financial History Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 p 223

- ↑ Variety film review; June 28, 1950, page 6.

- ↑ Harrison's Reports film review; July 1, 1950, page 102.

- ↑ Silver, Alain, and Elizabeth Ward, eds. Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style, film noir analysis by Carl Mecek, page 310, 3rd edition, 1992. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5.

- ↑ Otto Preminger at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley. The New York Times, film review, July 8, 1950. Last accessed: February 1, 2008.

- ↑ Variety. Staff film review, January 1, 1950.

- ↑ Trbic, Boris. Senses of Cinema, 2000.

- ↑ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

External links

- Where the Sidewalk Ends at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Where the Sidewalk Ends at the Internet Movie Database

- Where the Sidewalk Ends at AllMovie

- Where the Sidewalk Ends at the TCM Movie Database

- Where the Sidewalk Ends trailer on YouTube

Streaming audio

- Where the Sidewalk Ends "Night Cry", radio adaptation of original source material for Suspense show—1948