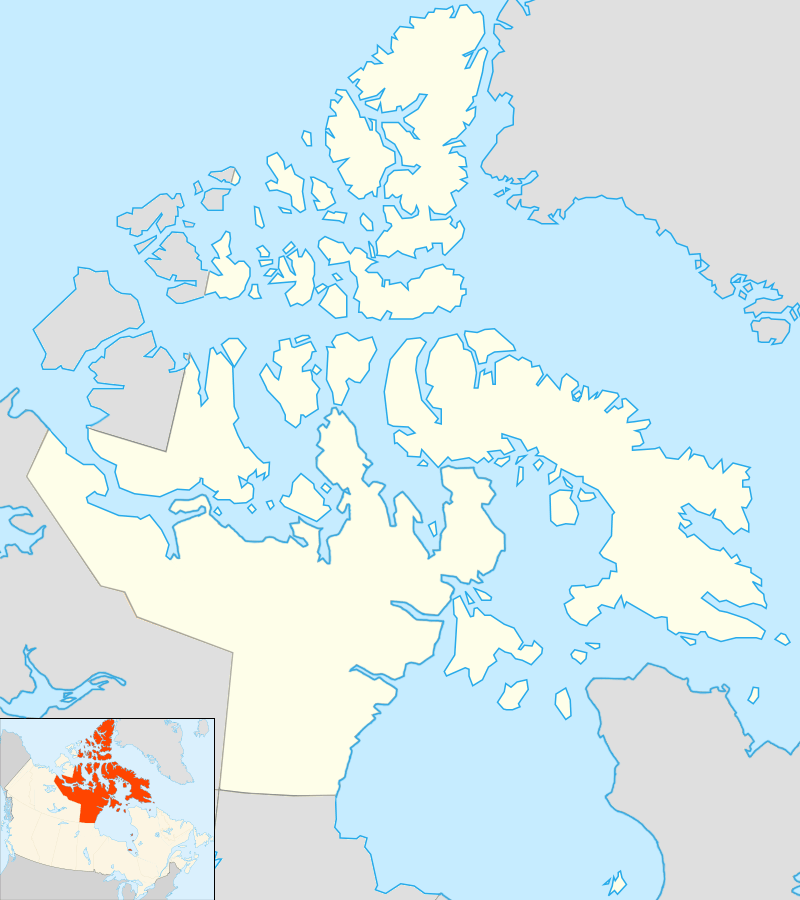

Whale Cove, Nunavut

| Whale Cove ᑎᑭᕋᕐᔪᐊᖅ Tikirarjuaq | |

|---|---|

| |

Whale Cove | |

| Coordinates: 62°10′22″N 092°34′46″W / 62.17278°N 92.57944°WCoordinates: 62°10′22″N 092°34′46″W / 62.17278°N 92.57944°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Territory | Nunavut |

| Region | Kivalliq Region |

| Electoral district | Arviat North-Whale Cove |

| Government[1][2] | |

| • Type | Hamlet Council |

| • Mayor | Stanley Adjuk Sr. |

| • Senior Administrative Officer | Paul Kaludjak |

| • MLA | George Kuksuk |

| Area[3] | |

| • Total | 283.65 km2 (109.52 sq mi) |

| Elevation[4] | 40 m (130 ft) |

| Population (2006)[3] | |

| • Total | 250 |

| • Density | 0.88/km2 (2.3/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| Canadian Postal code | X0C 0J0 |

| Area code(s) | 867 |

| Website | whalecove.ca |

Whale Cove (ᑎᑭᕋᕐᔪᐊᖅ in Inuktitut syllabics) (Tikiraqjuaq, meaning "long point"), is a hamlet located 45 mi (72 km) south of Rankin Inlet, 100 mi (161 km) north of Arviat, in Kivalliq Region, Nunavut, Canada, on the western shore of Hudson Bay.

The community is named for the many beluga whales which congregate off the coast. Many of the inhabitants hunt these whales every fall and use their by-products for their oil and food. Whale Cove, initially settled by three distinct Inuit groups (one inland and two coastal), is a relatively traditional community: 99% Inuit, who still wear fur, hunt, fish, eat raw meat and fish. Whale Cove is on the polar bear migration route.

Local Inuit, regularly travel by snowmobile in the winter or by boat in summer months between the hamlet of Rankin Inlet and Whale Cove a distance of 100 km (62 mi). The terrain is arctic tundra, this consists mostly of rocks, mosses and lichens.

As of the 2006 census, the population was 353, an increase of 15.7% from the 2001 census.[3]

History

Inuit in the Whale Cove area traded whale oil, baleen, furs, leather and walrus tusks with the Hudson's Bay Company since the mid-18th century when the HBC established their trading post at Churchill, Manitoba. [5]

Relocations 1950s

In the 1950s and 1960s Inuit were relocated in a series of moves from one hamlet to another, some of them arriving in Whale Cove, a hamlet created by the federal government for these Inuit groups. Some came from Ennadai Lake via Arviat to Whale Cove, other came from Back River via Garry Lake then Baker Lake to Whale Cove. By the 1970s Inuit living in Whale Cove represented boast coastal Inuit from Rankin Inlet and Arviat and different Caribou Inuit, from the Barren Grounds west of Hudson Bay, including the Ihalmiut ("people from beyond"), or Ahiarmiut ("the out-of-the-way dwellers") on the banks of the Kazan River, Ennadai Lake, Little Dubawnt Lake (Kamilikuak), and north of Thlewiaza (Kugjuaq; "Big River"), had been relocated in the 1950s Whale Cove and Henik Lake.[6][7][8][9][10] by the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources (now Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada). Their hunting experience was based almost entirely on "inland caribou herds that had thinned by the 1950s and left many families hungry. Coastal dwelling Inuit from Rankin Inlet and Arviat were relocated to Whale Cove from nearby coastal communities in order to aid the inlanders in adapting to a marine subsistence economy."[11]

Ennadai Lake relocations 1950-1960s

In the late 1960s a famine swept the land. Inuit were forced to walk towards places like Arviat to escape the desperation. Survivors who couldn't walk were airlifted to Whale Cove, Baker Lake and Rankin Inlet.[12]

Self-government

In 1971 in Toronto, at the first meeting of what would become the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Celestino Makpah, a traditional tool maker, who makes harpoons, ice chisels etc. but specializes in uluit,[13][Notes 1] the representative from Whale Cove described a number of ways in which the affairs of the Inuit of Keewatin were managed by the government and non-Inuit. Celestino recounted how, "a non-Native southerner started a private fishing enterprise on two lakes near Whale Cove without consulting the local people. At the time, the federal government decided what projects would or would not happen in the Northwest Territories."[14] "In our area, in Keewatin, there is no one managing the affairs of the Inuit other than the government. It is all government. I will give you an example: Near the surroundings of Whale Cove we have a large lake with plenty of fish. The white people control that lake just like they own it. There is a man, who is a tourist, who is probably one of the richest men there and he controls that lake. I don't mind at all if anyone is a tourist comes into our communities and fishes. The only thing I don't like about it is the government is the channel through which these private enterpriser go of course, because it is their land! So far there have been two large lakes which have been taken by private enterpriser with the help of the government, and this is one of the examples I really dislike. Since they are the government, even though they are aware of the rights of the native people they will not come and tell you "Do you know what your rights are? Do you know what you should do?" I think we, the Inuits, are just waiting for something to come up. "[15] "These should have been under our control,” Makpah said, “[the lakes] should never have been given to the American enterpriser."[14]

In 1973, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada initiated the Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project and anthropologist David Hoffman conducted fieldwork in Whale Cove as part of a team of experts contributing to this project.[16] The project under Milton Freeman,[17] "documented the total Inuit land use area of the Northwest Territories, then stretching from the Mackenzie River to east Baffin Island," to provide, in Freeman’s words, "information in support of the fact that Inuit have used and occupied this vast northern land since time immemorial and that they still use and occupy it to this day." Hoffmann admired the "precision with which Inuit – who did not ordinarily use maps and who often could not read English – were able to recall specific areas of use and the "incredible encyclopedic knowledge of the land," formed by generations of dependence on its living bounty."[14]

Economic development

Tikirarjuaq/Whale Cove companies and organizations, community and government services, the Kivalliq Inuit Association, First Air, Kivalliq Air, Arctic Co-operative, Nunavut Arctic College, Calm Air, Service Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Sakku Development Corp., Nunavut Development Corp, Agnico-Eagle, the North West Co., Kivalliq Partners in Development and ED&T. made presentations at the first Economic Development Day held at the Inuglak School gymnasium , in Tikirarjuaq/Whale Cove on 20 September 2011.[18]

According to the Nunavut Planning Commission Whale Cove region's potential non-renewable resources include: "gold, diamonds, uranium, base metals, and nickel-copper platinum group elements (PGEs)."[19]

Climate

Whale Cove has a Polar Climate (Köppen classification ET), and is above the tree line.

| Climate data for Whale Cove Airport | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | −5.9 | −6.3 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 14.4 | 23.3 | 28.4 | 27.5 | 21.5 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 28.4 |

| Record high °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

10.0 (50) |

10.5 (50.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

20.0 (68) |

21.0 (69.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

29.0 (84.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −27.1 (−16.8) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−20.3 (−4.5) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −30.6 (−23.1) |

−29.3 (−20.7) |

−23.6 (−10.5) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−16.1 (3) |

−24.0 (−11.2) |

−10.0 (14) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −34.1 (−29.4) |

−33.0 (−27.4) |

−28.2 (−18.8) |

−19.3 (−2.7) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

0.4 (32.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−19.8 (−3.6) |

−27.7 (−17.9) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −44.0 (−47.2) |

−47.5 (−53.5) |

−43.0 (−45.4) |

−36.0 (−32.8) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−34.0 (−29.2) |

−43.5 (−46.3) |

−47.5 (−53.5) |

| Record low wind chill | −63.8 | −68.9 | −61.1 | −48.4 | −34.7 | −16.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −16.9 | −39.6 | −53.6 | −59.3 | −68.9 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 15.1 (0.594) |

11.7 (0.461) |

17.2 (0.677) |

20.9 (0.823) |

16.9 (0.665) |

32.6 (1.283) |

39.0 (1.535) |

62.4 (2.457) |

51.6 (2.031) |

32.5 (1.28) |

29.6 (1.165) |

21.3 (0.839) |

350.6 (13.803) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.4 (0.016) |

5.9 (0.232) |

25.2 (0.992) |

39.0 (1.535) |

62.4 (2.457) |

45.7 (1.799) |

9.1 (0.358) |

0.1 (0.004) |

0.0 (0) |

187.7 (7.39) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 16.0 (6.3) |

11.8 (4.65) |

18.0 (7.09) |

20.7 (8.15) |

11.0 (4.33) |

7.4 (2.91) |

0.0 (0) |

0.1 (0.04) |

6.0 (2.36) |

23.4 (9.21) |

30.6 (12.05) |

22.6 (8.9) |

167.5 (65.94) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.8 | 6.6 | 8.4 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 10.3 | 14.7 | 13.7 | 13.0 | 10.6 | 8.1 | 116.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 7.2 | 10.3 | 14.7 | 11.8 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 49.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 8.7 | 6.7 | 8.4 | 6.8 | 5.2 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 10.0 | 10.6 | 8.4 | 68.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64.3 | 67.8 | 70.0 | 80.2 | 84.7 | 75.2 | 73.8 | 72.4 | 76.8 | 86.4 | 79.6 | 71.9 | 75.3 |

| Source: Environment Canada Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010[20] | |||||||||||||

Notable people from Tikirarjuaq

John Adjuk (1913 Back River -2006 Whale Cove) moved with his family to Whale Cove in March 1964 from Baker Lake. Originally from the Back River area (Chantrey Inlet) north of Baker Lake, living the traditional way of life on the land, he moved to Garry Lake area. Following famine in the Garry Lake area, he was evacuated to Baker (Lake Qamanittuaq) in 1955. In 1955 they returned to Garry Lake but in early 1958 the family of five was evacuated to Baker Lake when famine struck the land. The Hanningajurmiut, or Hanningaruqmiut, or Hanningajulinmiut {"the people of the place that lies across"} lived at Garry Lake, south of the Utkuhiksalingmiut. Many Hanningajurmiut starved in 1958 when the caribou bypassed their traditional hunting grounds, but the 31 who survived were relocated to Baker. Most never returned permanently to Garry Lake.[21][Notes 2] In March, 1964, the Adjuk family, which now included 6 daughters, moved to Whale Cove because it was thought the hunting and fishing was better. [22]

Education

Nunavut Arctic College has a branch in Whale Cove.

Notes

- ↑ Celestino instructs students at the Maani Ulujuk High School.

- ↑ First generation Inuit artists such as Jessie Oonark, Marion Tuu'luq and camp leader Luke Anguhadluq (1895-1982) were also born in the Back River area of Nunavut and were evacuated to Baker Lake because of starvation in 1967.

Citations

- ↑ Nunavummiut vie for council positions in upcoming hamlet elections

- ↑ Results for the constituency of Arviat North-Whale Cove at Elections Nunavut

- 1 2 3 2006 census

- ↑ Elevation at airport. Canada Flight Supplement. Effective 0901Z 15 September 2016 to 0901Z 10 November 2016

- ↑ Welch & Payne 2012.

- ↑ Mowat, Farley (2001). Walking on the land. South Royalton, Vt.: Steerforth Press. ISBN 1-58642-024-0. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ Madsen, Kirsten. "Project Caribou" (PDF). Whitehorse, Yukon Territory: Yukon Department of Environment. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ↑ Mowat, Farley (2005). No Man's River. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 0-7867-1692-4. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Remembering Kikkik". nunatsiaq.com. 2002-06-21. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ↑ Layman, Bill. "Nu-thel-tin-tu-eh and the Thlewiaza River, The Land of the Caribou Inuit and The Barren Ground Caribou Dene". churchillrivercanoe.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ Argetsinger & 2009 24.

- ↑ Steenhoven 1955.

- ↑ Rankin Inlet profiles

- 1 2 3 Argetsinger & 2009 18.

- ↑ ITK 1971.

- ↑ Argetsinger & 2009 23.

- ↑ Freeman 1976.

- ↑ Greer 2011.

- ↑ NPC 2009-13.

- ↑ "Whale Cove A" (CSV (4222 KB)). Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2303986. Retrieved 2013-11-27.

- ↑ Tester & Kulchyski 2001.

- ↑ Kuehl 2002.

See also

References

- Argetsinger, Timothy H. Aqukkasuk (2009), The Nature of Inuit Self-Governance in Nunavut Territory (PDF), Hanover, NH: Native American Studies, Dartmouth College

- Greer, Darrell (20 September 2011), Plenty to offer in Whale Cove: Community highlights services, workforce on special day, Northern News Services

- ITK (18 February 1971), Transcript of First ITC Meeting, Toronto Ontario: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, retrieved 22 September 2013

- ITK (7 September 1985), Elders Return To Ennadai Lake, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, retrieved 25 September 2013

- Kuehl, Gerald (2002), John Adjuk, retrieved 20 September 2013

- "Tuhaalruuqtut Ancestral Sounds". virtualmuseum.ca. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- Freeman, Milton (1976), Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project: A Report, Department of Indian and Northern Affairs

- Steenhoven, Geert van Steenhoven (Spring 1968), Ennadai Lake People, The Beaver Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - Tester, F.J.; Kulchyski, Peter (1 January 2001), Tammarniit (Mistakes), Inuit Relocation in the Eastern Arctic, 1939-63, Vancouver: UBC Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0452-3, retrieved 2008-03-09

- NPC (2009–13), Whale Cove, Nunavut Planning Commission

- Serkoak, David (1985), Ennadai Lake, Inuktitut Magazine

- Welch, Deborah; Payne, Michael (2012), Whale Cove, Canadian Encyclopedia

Further reading

- Inuglak School (Whale Cove, Nunavut). The Lonely Inukshuk. Markham, Ont: Scholastic Book Fairs, 1999. ISBN 0-590-51650-7