Wangfujing

Coordinates: 39°54′40.16″N 116°24′18.99″E / 39.9111556°N 116.4052750°E

| Prince's Mansion Well, Wangfu Well | |

|

Deep-fried starfish for sale as a seafood at Wangfujing snack street |

Wangfujing (Chinese: 王府井; pinyin: Wángfǔjǐng; literally: "Prince's Mansion Well") is one of the most famous shopping streets of Beijing, China, located in Dongcheng District. The majority of the main area is pedestrianised and very popular shopping place for both tourists and residents of the capital. Since the middle of the Ming Dynasty there have been commercial activities in this place. In the Qing Dynasty, ten aristocratic estates and princess residence were built here, soon after when a well full of sweet water was discovered, thereby giving the street its name "Wang Fu" (princely residence), "Jing" (well). Many exotic foods are served on Wangfujing snack street.[1]

Location

It starts from Wangfujing Nankou ("south entrance"), where the Oriental Plaza and the Beijing Hotel are located and the Wangfujing Subway Station north exits. The street then heads north, passing the Wangfujing Xinhua Bookstore, the Beijing Department Store as well as the Beijing Foreign Languages Bookstore before ending at the Sun Dong An Plaza and St. Joseph's Church.

History

The street was also previously known as Morrison Street in English, after the Australian journalist George Ernest Morrison. Wangfujing is also one of the traditional downtown areas of Beijing, along with Liulichang.

Until the late 1990s, the street was open to traffic. Modifications in 1999 and 2000 made much of Wangfujing Street pedestrian only (aside from the tour trolley). Now through traffic detours to the east of the street.

2011 Chinese pro-democracy protests

The 2011 Chinese pro-democracy protests (simplified Chinese: 中国茉莉花革命; traditional Chinese: 中國茉莉花革命), also known as the Chinese Jasmine Revolution,[2] refer to public assemblies in over a dozen cities in China starting on 20 February 2011, inspired by and named after the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia;[3][4] the actions that took and take place at protest sites, and response by the Chinese government to the calls and action.[4][5]

Initially, organizers suggested shouting slogans on 20 February. After participants and journalists had been beaten and arrested.[4] After the police response to the protests on 20 February, the organizers urged the participants not to shout slogans any more, but simply to stroll silently at the respective protest sites. The call to use "strolling" tactics for the 27 February gatherings was made on the Boxun.com website on 22 February.[4] Prior to the planned 27 February gathering in front of a McDonald's restaurant in Beijing, authorities installed metal corrugated fencing outside the restaurant and outside the home of Nobel laureate and dissident Liu Xiaobo.[5] Hundreds of uniformed and plain-clothed security staff and volunteers wearing red armbands were pre-emptively stationed at Wangfujing. Their presence disrupted normal shopping and attracted onlookers.[6] Police began to clear the rendezvous area half an hour after the designated assembly time.[7]

On 25 February, several foreign journalists were contacted by police and told that they could not conduct interviews without applying for permission.[5] Regulations issued by the Chinese government forbid entry by foreign reporters into the Wangfujing shopping district in Beijing or the People’s Park in central Shanghai without a special permit. Enforcement of the new rules on Sunday 28 February resulted in beating of one camera operator and detention of several reporters for several hours before their release and confiscation of their materials.[8][9]

Several foreign journalists were physically beaten by the police, with many others physically pushed by the police, their cameras confiscated and footage deleted.[10] CNN reporter Eunice Yoon reported that a policeman in Wangfujing knocked a camera out of her colleague Jo Ling Kent's hand and six police officers physically forced them into a bank, where they were detained for half an hour.[10] Yoon remarked after the incident that "there had been no protests for us to cover", and that the incident "show[ed] how incredibly terrified and paranoid the Chinese authorities are".[11] CBS News producer Connie Young was also forcefully carried off by plain clothes police officers and detained after she filmed VOA bureau chief, Stephanie Ho, being wrestled to the ground by plain clothes police officers. Ho was filming when she was quickly attacked and detained by uniformed and plain clothes police officers.

CNN journalist Eunice Yoon and her news crew headed out to Wangfujing to cover the "response to anonymous calls on the Internet to stage protests and begin a Tunisia-style "Jasmine Revolution" in China",[11] was physically handled by police in Beijing on 27 February at arrival near the protest site. She wrote: "What makes China's treatment of the international press so bewildering is that there had been no protests for us to cover here..... My own experience and those of my colleagues show how incredibly terrified and paranoid the Chinese authorities are of any anti-government movement forming in China."[10]

On 6 May, in Beijing, journalists saw no obvious sign of protesters.[12] Large contingent of plain-clothed security personnel were reported in and around Wangfujing, Xidan and Zhongguancun.[13]

On 13 March, according to Deutsche Presse-Agentur, there were several hundred police in the Wangfujing and Xidan districts in Beijing, including uniformed police with dogs, paramilitary police, plain-clothes police, special forces units and security guards.[14] More than 40 police were present at the Peace Cinema in Shanghai.[14] According to Agence France-Presse, "there was no massive police presence [at Wangfujing] as seen on previous Sundays."[15]

Stores

Wangfujing is now home to around 280 famous Beijing brands, such as Shengxifu hat store, Tongshenghe shoe shop, and the Wuyutai tea house. A photo studio which took formal photos of the first Chinese leadership, the New China Woman and Children Department Store helped established by Soong Ching-ling (Madame Sun Yat-sen) are also located on the street.

Food and snacks

The Wangfujing snack street, located in hutongs just west of the main street, is densely packed with restaurants and street food stalls. The food stalls serves a wide variety of common and exotic street food. More common fare such as chuanr (meat kebabs, commonly made of lamb) and desserts, such as tanghulu or candied fruits on a stick, are among the most popular.

Further north and perpendicular to Wangfujing is Donghuamen Street, which has a night food market of its own.

Transport

The Wangfujing Station of Beijing Subway Line 1 is located at the intersection of Wangfujing Street and Chang'an Avenue.

Gallery

- Wangfujing dajie (大街) or pedestrian street

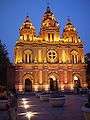

St. Joseph's Church

St. Joseph's Church

See also

References

- ↑ Latimer D. (2014) The Improbable Beijing Guidebook, Sinomaps, Beijing, ISBN 978-7-5031-8451-2, p.52

- ↑ Ramzy, Austin (21 February 2011). "China Cracks Down After 'Jasmine Revolution' Protest Call". TIME. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ↑ Hille, Kathrin (23 February 2011). "'Jasmine revolutionaries' call for weekly China protests". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Organizers urge sustained street protests in China". Mercury News. AP. 23 February 2011. Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 Pierson, David (26 February 2011). "Online call for protests in China prompts crackdown". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ Page, Jeremy; James T. Areddy (27 February 2011). "China Takes Heavy Hand to Light Protests". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ↑ "China's Wen addresses concerns amid protest call". France 24. 27 February 2011. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ↑ Andrew Jacobs (1 March 2011). "Chinese Move to Stop Reporting on Protests". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ↑ Ananth Krishnan (1 March 2011). "Chinese government places media restrictions after protest threat". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Yoon, Eunice (28 February 2011). "Getting harassed by the Chinese police". CNN. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- 1 2 : CNN Beijing correspondent, Eunice Yoon (9 March 2011). "Getting harassed by the Chinese police – Business 360 – CNN.com Blogs". Business.blogs.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Blanchard, Ben (6 March 2011). "Beijing says jasmine protest calls doomed to fail". Reuters. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Staff Reporters (7 March 2011). "Police out in force again to stop 'jasmine' rallies flowering", South China Morning Post

- 1 2 "China keeps heavy security on fourth "Jasmine" day". Monsters and Critics. DPA. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ "China arrests more activists for urging protests". Emirates24. AFP. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wangfujing. |

- Old brands of Beijing (Chinese)

- Wangfujing Website