Wallace Berman

| Wallace Berman | |

|---|---|

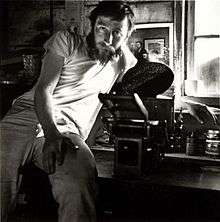

Wallace Berman, Self Portrait Crater Lane, 1955 | |

| Born |

February 18, 1926 Staten Island, New York |

| Died |

February 18, 1976 (aged 50) Topanga Canyon, California |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Assemblage art |

Wallace Berman (February 18, 1926 – February 18, 1976) was an American visual and assemblage artist. He has been called the "father" of assemblage art[1] and a "crucial figure in the history of postwar California art".[2]

Personal life and education

Wallace Berman was born in Staten Island, New York in 1926. In the 1930s his family moved to Boyle Heights, Los Angeles.[3] Berman was discharged from high school for gambling in the early 1940s and became involved in the West Coast jazz scene. Berman wrote a song with Jimmy Witherspoon.[4] He attended classes at Jepson Art Institute and Chouinard Art Institute in the 1940s. For a few years from 1949 he worked in a factory finished furniture. It was at the factory where he began creating sculptures from wood scraps. This led to him becoming a full-time artist by the early 1950s, and an involvement in the Beat Movement. He moved from Los Angeles to San Francisco in late 1957 where he mostly focused on his magazine Semina, which consisted of poetry, photographs, texts, drawings and images assembled by Berman. In 1961 he came back to L.A., then moved to Topanga Canyon in 1965. He started creating his series of Verifax Collages in 1963 or 1964.[1] Director Dennis Hopper, a collector of Berman's work, gave Berman a small role in his 1968 film Easy Rider.[5] He produced work until his sudden death in a car accident caused by a drunk driver,[6] in 1976.[1] Interestingly, Berman had said to his mother as a child he would die on his 50th birthday, and indeed he did die February 18, 1976...his fiftieth birthday. ref. Lost and Found California, Four decades of assemblage art, Corcoran, Wayne, Pence, 1988 pg.119.

Artistic career

"His art embodied the kind of interdisciplinary leanings and interests that, in time, would come to help characterize the Beat movement as a whole."

-Andy Brumer[4]

Berman has been called the "father" of assemblage art. He created "Verifax collages", which consist of photocopies of images from magazines and newspapers, mounted onto a flat surface in a collage fashion, mixed with occasional solid areas of acrylic paint .[1] Berman would use a Verifax photocopy machine (Kodak) to make copies of the images which he would often juxtapose in a grid format. Berman sought influence in not only those of his Beat circle, but in Surrealism and Dada as well as the Kabbalah.[4] The influence of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism is seen in his collages and other works such as his later inscriptions in-situ in Hebrew letters, and his only film, Aleph, a silent film that explores life, death, politics, and pop culture.[7] His involvement with the jazz scene allowed him opportunities to work with jazz musicians, creating bebop album covers for Charlie Parker.[8]

In 1957 Berman had his first exhibition of his artworks at the newly opened Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. His friends were the curators/owners of the Gallery, Ed Kienholz and Walter Hopps. After the opening the L.A. vice squad got a telephone tip from an anonymous caller and during the raid they found what was deemed to be a pornographic image by Cameron Parsons entitled "Peyote Vision"[9] at the bottom of one of Berman's assemblage works. He would later be convicted of displaying lewd & obscene materials. At the summation in the courtroom Berman wrote on the blackboard "There is no justice, only revenge" [10] His actor friend Dean Stockwell would pay the $150.00 fine. That would be the last public gallery show for Berman.

His mail art publication, Semina, was a series of folio packages that were limited edition and sent or given to his friends. Semina consisted of collages mixed with poetry by writers Michael McClure, Philip Lamantia, David Meltzer, Charles Bukowski, William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Jean Cocteau, John Kelly Reed[11] and by Berman himself, which he published under the pseudonym Pantale Xantos.[3][8] Semina was published from 1955 to 1964.[2]

Legacy

His likeness appears in the second row of the Beatles' 1967 Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover. The portrait is from a photograph taken by Dean Stockwell. It is directly above John Lennon, two rows up, next to Tony Curtis.[12] In 1992 Berman's papers were donated to the Archives of American Art by his son, Tosh Berman.[1]

Notable exhibitions

- Looking for Mushrooms, 2008; Ludwig Museum[13]

- Trace du Sacre, 2008; Centre Pompidou[13]

- Los Angeles 1955-1985 2006; Centre Pompidou

- California Modern, 2006; Orange County Museum of Art[13]

- Subway Series: The New York Yankees and the American Dream, 2004; Bronx Museum of the Arts[13]

- Evidence of Impact: Art and Photography 1963-1978, 2004; Whitney Museum of American Art[13]

- Solo exhibition: Exodus Gallery, San Pedro, 1957

- Solo exhibition: Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles, 1957

Notable collections

- Untitled, 1967; Norton Simon Museum[14]

- di Rosa[15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Wallace Berman papers, 1907-1979, (bulk 1955-1979)". Finding Aid. Archives of American Art. 2001. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- 1 2 "Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle". Exhibits. Grey Art Gallery. 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- 1 2 "Wallace Berman". Verdant Press. 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 Andy Brumer. "Wallace Berman". Biographical. Beat Museum. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Maurice Berger (2004). "Untitled". Collections. The Jewish Museum. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ Randy Kennedy (2008). "Richard Prince and Wallace Berman's mutual focus: Women and sensuality". Arts. The New York Times. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "Wallace Berman (b. 1946)". UbuWeb. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- 1 2 "Allan Publishes on Wallace Berman, Jazz, and L.A. in the 1950s". Resources. Seattle University. 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ http://www.bampfa.berkeley.edu/press/release/TXT0142

- ↑ http://stockwellsassies.tripod.com/articles/Wally_Berman.html

- ↑ http://writing.upenn.edu/library/Fredman-Stephen_Semina.html

- ↑ "Dean Stockwell Art". Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Wallace Berman". Berman. Kohn Gallery. 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "Untitled". Browse by Artist. Norton Simon Museum. 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "The Collection". dirosaart.org. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

Further reading

- Glicksman et al. Wallace Berman: Retrospective. Otis Art Institute Gallery, Los Angeles. Los Angeles: Fellows of Contemporary Art (1978).

- Support the Revolution. Institute of Contemporary Art, Amsterdam. New York: Distributed Art Publishers (1992). ISBN 90-800968-3-0

- Sophie Dannenmüller: "In Fac Simile Veritas, les Verifax Collages de Wallace Berman," Les Cahiers du Musée national d'art moderne, Editions du Centre Pompidou, Paris, n° 92, summer 2005, p. 130-143

- Fredman, Stephen and Michael Duncan. Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle. Santa Monica: Santa Monica Museum of Art (2005). ISBN 1-933045-10-8

- Dannenmüller, Sophie. Wallace Berman - Verifax Collages. Paris: frank elbaz gallery (2009)

- Dannenmüller, Sophie. Wallace Berman - Be-Bop Kabbalah. Paris: frank elbaz gallery (2010)

- Bradnock, Lucy. ""Mantras of Gibberish": Wallace Berman's Visions of Artaud". Art History, vol. 35 (3), June 2012, pp. 622-643

External links

- Works by or about Wallace Berman in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- City of Degenerate Angels: Wallace Berman, Jazz and Semina in Postwar Los Angeles by Ken D. Allan in Art Journal

- galerie frank elbaz: Wallace Berman

- Wallace Berman at Kadist Art Foundation