Sodium channel

Sodium channels are integral membrane proteins that form ion channels, conducting sodium ions (Na+) through a cell's plasma membrane.[1][2] They are classified according to the trigger that opens the channel for such ions, i.e. either a voltage-change ("Voltage-gated", "voltage-sensitive", or "voltage-dependent" sodium channel also called "VGSCs" or "Nav channel") or a binding of a substance (a ligand) to the channel (ligand-gated sodium channels).

In excitable cells such as neurons, myocytes, and certain types of glia, sodium channels are responsible for the rising phase of action potentials.

Selectivity

Sodium channels are highly selective for the transport of sodium ions across cell membranes. The high selectivity with respect to the potassium ion is achieved in many different ways. All involve encapsulation of the sodium ion in a cavity of specific size within a larger molecule.[3]

Voltage-gated

Structure

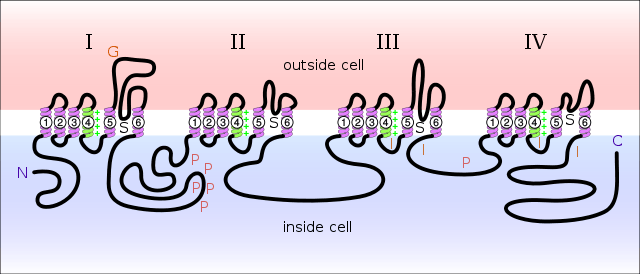

Sodium channels consist of large α subunits that associate with proteins, such as β subunits. An α subunit forms the core of the channel and is functional on its own. When the α subunit protein is expressed by a cell, it is able to form channels that conduct Na+ in a voltage-gated way, even if β subunits or other known modulating proteins are not expressed. When accessory proteins assemble with α subunits, the resulting complex can display altered voltage dependence and cellular localization.

The α-subunit has four repeat domains, labeled I through IV, each containing six membrane-spanning segments, labeled S1 through S6. The highly conserved S4 segment acts as the channel's voltage sensor. The voltage sensitivity of this channel is due to positive amino acids located at every third position.[5] When stimulated by a change in transmembrane voltage, this segment moves toward the extracellular side of the cell membrane, allowing the channel to become permeable to ions. The ions are conducted through a pore, which can be broken into two regions. The more external (i.e., more extracellular) portion of the pore is formed by the "P-loops" (the region between S5 and S6) of the four domains. This region is the most narrow part of the pore and is responsible for its ion selectivity. The inner portion (i.e., more cytoplasmic) of the pore is formed by the combined S5 and S6 segments of the four domains. The region linking domains III and IV is also important for channel function. This region plugs the channel after prolonged activation, inactivating it.

Gating

Voltage-gated Na+ channels have three main conformational states: closed, open and inactivated. Forward/back transitions between these states are correspondingly referred to as activation/deactivation (between closed and open), inactivation/reactivation (between open and inactivated), and recovery from inactivation/closed-state inactivation (between inactivated and closed). Closed and inactivated states are ion impermeable.

Before an action potential occurs, the axonal membrane is at its normal resting potential, and Na+ channels are in their deactivated state, blocked on the extracellular side by their activation gates. In response to an electric current (in this case, an action potential), the activation gates open, allowing positively charged Na+ ions to flow into the neuron through the channels, and causing the voltage across the neuronal membrane to increase. Because the voltage across the membrane is initially negative, as its voltage increases to and past zero, it is said to depolarize. This increase in voltage constitutes the rising phase of an action potential.

At the peak of the action potential, when enough Na+ has entered the neuron and the membrane's potential has become high enough, the Na+ channels inactivate themselves by closing their inactivation gates. The inactivation gate can be thought of as a "plug" tethered to domains III and IV of the channel's intracellular alpha subunit. Closure of the inactivation gate causes Na+ flow through the channel to stop, which in turn causes the membrane potential to stop rising. With its inactivation gate closed, the channel is said to be inactivated. With the Na+ channel no longer contributing to the membrane potential, the potential decreases back to its resting potential as the neuron repolarizes and subsequently hyperpolarizes itself. This decrease in voltage constitutes the falling phase of the action potential.

When the membrane's voltage becomes low enough, the inactivation gate reopens and the activation gate closes in a process called deinactivation, or removal of inactivation. With the activation gate closed and the inactivation gate open, the Na+ channel is once again in its deactivated state, and is ready to participate in another action potential.

When any kind of ion channel does not inactivate itself, it is said to be persistently (or tonically) active. Some kinds of ion channels are naturally persistently active. However, genetic mutations that cause persistent activity in other channels can cause disease by creating excessive activity of certain kinds of neurons. Mutations that interfere with Na+ channel inactivation can contribute to cardiovascular diseases or epileptic seizures by window currents, which can cause muscle and/or nerve cells to become over-excited.

Modeling the behavior of gates

The temporal behavior of Na+ channels can be modeled by a Markovian scheme or by the Hodgkin–Huxley-type formalism. In the former scheme, each channel occupies a distinct state with differential equations describing transitions between states; in the latter, the channels are treated as a population that are affected by three independent gating variables. Each of these variables can attain a value between 1 (fully permeant to ions) and 0 (fully non-permeant), the product of these variables yielding the percentage of conducting channels. The Hodgkin–Huxley model can be shown to be equivalent to a Markovian model.

Impermeability to other ions

The pore of sodium channels contains a selectivity filter made of negatively charged amino acid residues, which attract the positive Na+ ion and keep out negatively charged ions such as chloride. The cations flow into a more constricted part of the pore that is 0.3 by 0.5 nm wide, which is just large enough to allow a single Na+ ion with a water molecule associated to pass through. The larger K+ ion cannot fit through this area. Ions of different sizes also cannot interact as well with the negatively charged glutamic acid residues that line the pore.

Diversity

Voltage-gated sodium channels normally consist of an alpha subunit that forms the ion conduction pore and one to two beta subunits that have several functions including modulation of channel gating.[6] Expression of the alpha subunit alone is sufficient to produce a functional channel.

Alpha subunits

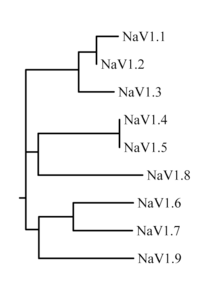

The family of sodium channels has nine known members, with amino acid identity >50% in the trans-membrane segments and extracellular loop regions. A standardized nomenclature for sodium channels is currently used and is maintained by the IUPHAR.[7][8]

The proteins of these channels are named Nav1.1 through Nav1.9. The gene names are referred to as SCN1A through SCN11A (the SCN6/7A gene is part of the Nax sub-family and has uncertain function). The likely evolutionary relationship between these channels, based on the similarity of their amino acid sequences, is shown in figure 1. The individual sodium channels are distinguished not only by differences in their sequence but also by their kinetics and expression profiles. Some of this data is summarized in table 1, below.

| Protein name | Gene | Expression profile | Associated human channelopathies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nav1.1 | SCN1A | Central neurons, [peripheral neurons] and cardiac myocytes | febrile epilepsy, GEFS+, Dravet syndrome (also known as severe myclonic epilepsy of infancy or SMEI), borderline SMEI (SMEB), West syndrome (also known as infantile spasms), Doose syndrome (also known as myoclonic astatic epilepsy), intractable childhood epilepsy with generalized tonic-clonic seizures (ICEGTC), Panayiotopoulos syndrome, familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM), familial autism, Rasmussens's encephalitis and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome[9] |

| Nav1.2 | SCN2A | Central neurons, peripheral neurons | inherited febrile seizures and epilepsy |

| Nav1.3 | SCN3A | Central neurons, peripheral neurons and cardiac myocytes | epilepsy, pain |

| Nav1.4 | SCN4A | Skeletal muscle | hyperkalemic periodic paralysis, paramyotonia congenita, and potassium-aggravated myotonia |

| Nav1.5 | SCN5A | Cardiac myocytes, uninnervated skeletal muscle, central neurons, gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells and Interstitial cells of Cajal | Cardiac: Long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation; Gastrointestinal: Irritable bowel syndrome;[10] |

| Nav1.6 | SCN8A | Central neurons, dorsal root ganglia, peripheral neurons, heart, glia cells | epilepsy |

| Nav1.7 | SCN9A | Dorsal root ganglia, sympathetic neurons, Schwann cells, and neuroendocrine cells | erythromelalgia, PEPD, channelopathy-associated insensitivity to pain and recently discovered a disabling form of fibromyalgia (rs6754031 polymorphism)[11] |

| Nav1.8 | SCN10A | Dorsal root ganglia | pain, neuropsychiatric disorders |

| Nav1.9 | SCN11A | Dorsal root ganglia | pain |

| Nax | SCN7A | heart, uterus, skeletal muscle, astrocytes, dorsal root ganglion cells | none known |

Beta subunits

Sodium channel beta subunits are type 1 transmembrane glycoproteins with an extracellular N-terminus and a cytoplasmic C-terminus. As members of the Ig superfamily, beta subunits contain a prototypic V-set Ig loop in their extracellular domain. It is interesting to note that beta subunits share no homology with their counterparts of calcium and potassium channels.[12] Instead, they are homologous to neural cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) and the large family of L1 CAMs. There are four distinct betas named in order of discovery: SCN1B, SCN2B, SCN3B, SCN4B (table 2). Beta 1 and beta 3 interact with the alpha subunit non-covalently, whereas beta 2 and beta 4 associate with alpha via disulfide bond.[13]

Role of beta subunits as cell adhesion molecules

In addition to regulating channel gating, sodium channel beta subunits also modulate channel expression and form links to the intracelluar cytoskeleton via ankyrin and spectrin.[6][14][15] Voltage-gated sodium channels also assemble with a variety of other proteins, such as FHF proteins (Fibroblast growth factor Homologous Factor), calmodulin, cytoskeleton or regulatory kinases,[16][17][18][19][20] which form a complex with sodium channels, influencing its expression and/or function. Several beta subunits interact with one or more extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules. Contactin, also known as F3 or F11, associates with beta 1 as shown via co-immunoprecipitation.[21] Fibronectin-like (FN-like) repeats of Tenascin-C and Tenascin-R bind with beta 2 in contrast to the Epidermal growth factor-like (EGF-like) repeats that repel beta2.[22] A disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) 10 sheds beta 2's ectodomain possibly inducing neurite outgrowth.[23] Beta 3 and beta 1 bind to neurofascin at Nodes of Ranvier in developing neurons.[24]

| Protein name | Gene link | Assembles with | Expression profile | Associated human channelopathies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Navβ1 | SCN1B | Nav1.1 to Nav1.7 | Central Neurons, Peripheral Neurons, skeletal muscle, heart, glia | epilepsy (GEFS+) |

| Navβ2 | SCN2B | Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.5 to Nav1.7 | Central Neurons, peripheral neurons, heart, glia | none known |

| Navβ3 | SCN3B | Nav1.1 to Nav1.3, Nav1.5 | central neurons, adrenal gland, kidney, peripheral neurons | none known |

| Navβ4 | SCN4B | Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.5 | heart, skeletal muscle, central and peripheral neurons | none known |

Ligand-gated

Ligand-gated sodium channels are activated by binding of a ligand instead of a change in membrane potential.

They are found, e.g. in the neuromuscular junction as nicotinic receptors, where the ligands are acetylcholine molecules. Most channels of this type are permeable to potassium to some degree as well as to sodium.

Role in action potential

Voltage-gated sodium channels play an important role in action potentials. If enough channels open when there is a change in the cell's membrane potential, a small but significant number of Na+ ions will move into the cell down their electrochemical gradient, further depolarizing the cell. Thus, the more Na+ channels localized in a region of a cell's membrane the faster the action potential will propagate and the more excitable that area of the cell will be. This is an example of a positive feedback loop. The ability of these channels to assume a closed-inactivated state causes the refractory period and is critical for the propagation of action potentials down an axon.

Na+ channels both open and close more quickly than K+ channels, producing an influx of positive charge (Na+) toward the beginning of the action potential and an efflux (K+) toward the end.

Ligand-gated sodium channels, on the other hand, create the change in the membrane potential in the first place, in response to the binding of a ligand to it.

Pharmacologic modulation

Blockers

Activators

The following naturally produced substances persistently activate (open) sodium channels:

- Alkaloid-based toxins

- aconitine

- batrachotoxin

- brevetoxin

- ciguatoxin

- delphinine

- some grayanotoxins, e.g., grayanotoxin I (other granotoxins inactive, or close, sodium channels)

- veratridine

Gating modifiers

The following toxins modify the gating of sodium channels:

- Peptide-based toxins

- μ-conotoxin

- δ-atracotoxin[25]

- Scorpion venom toxins,[26]

See also

References

- ↑ Jessell TM, Kandel ER, Schwartz JH (2000). Principles of Neural Science (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 154–69. ISBN 0-8385-7701-6.

- ↑ Bertil Hillel (2001). Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes (3rd ed.). Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer. pp. 73–7. ISBN 0-87893-321-2.

- ↑ Lim, Carmay; Dudev, Todor (2016). "Chapter 10. Potassium Versus Sodium Selectivity in Monovalent Ion Channel Selectivity Filters". In Astrid, Sigel; Helmut, Sigel; Roland K.O., Sigel. The Alkali Metal Ions: Their Role in Life. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 16. Springer. pp. 325–347. doi:10.1007/978-4-319-21756-7_9.

- ↑ Yu FH, Catterall WA (2003). "Overview of the voltage-gated sodium channel family". Genome Biol. 4 (3): 207. doi:10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-207. PMC 153452

. PMID 12620097.

. PMID 12620097. - ↑ Nicholls, Martin, Fuchs, Brown, Diamond, Weisblat. (2012) "From Neuron to Brain," 5th ed. pg. 86

- 1 2 Isom LL (2001). "Sodium channel beta subunits: anything but auxiliary". Neuroscientist. 7 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1177/107385840100700108. PMID 11486343.

- ↑ IUPHAR – International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology

- ↑ Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG (2005). "International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels". Pharmacol Rev. 57 (4): 397–409. doi:10.1124/pr.57.4.4. PMID 16382098.

- ↑ Lossin C. "SCN1A infobase". Retrieved 2009-10-30.

compilation of genetic variations in the SCN1A gene that alter the expression or function of Nav1.1

- ↑ Beyder A, Mazzone A, Strege PR, Tester DJ, Saito YA, Bernard CE, Enders FT, Ek WE, Schmidt PT, Dlugosz A, Lindberg G, Karling P, Ohlsson B, Gazouli M, Nardone G, Cuomo R, Usai-Satta P, Galeazzi F, Neri M, Portincasa P, Bellini M, Barbara G, Camilleri M, Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, D'Amato M, Ackerman MJ, Farrugia, G. "Loss-of-Function of the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel NaV1.5 (Channelopathies) in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome.". Gastroenterology. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.054.

- ↑ Vargas-Alarcon G, Alvarez-Leon E, Fragoso JM, et al. (2012). "A SCN9A gene-encoded dorsal root ganglia sodium channel polymorphism associated with severe fibromyalgia". BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 13: 23. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-23. PMC 3310736

. PMID 22348792.

. PMID 22348792. - ↑ Catterall WA (April 2000). "From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels". Neuron. 26 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81133-2. PMID 10798388.

- ↑ Isom LL, De Jongh KS, Patton DE, Reber BF, Offord J, Charbonneau H, Walsh K, Goldin AL, Catterall WA (May 1992). "Primary structure and functional expression of the beta 1 subunit of the rat brain sodium channel". Science. 256 (5058): 839–42. doi:10.1126/science.1375395. PMID 1375395.

- ↑ Malhotra JD, Kazen-Gillespie K, Hortsch M, Isom LL (April 2000). "Sodium channel beta subunits mediate homophilic cell adhesion and recruit ankyrin to points of cell-cell contact". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (15): 11383–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.15.11383. PMID 10753953.

- ↑ Malhotra JD, Koopmann MC, Kazen-Gillespie KA, Fettman N, Hortsch M, Isom LL (July 2002). "Structural requirements for interaction of sodium channel beta 1 subunits with ankyrin". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (29): 26681–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202354200. PMID 11997395.

- ↑ Cantrell AR, Catterall WA (June 2001). "Neuromodulation of Na+ channels: an unexpected form of cellular plasticity". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 (6): 397–407. doi:10.1038/35077553. PMID 11389473.

- ↑ Isom LL (February 2001). "Sodium channel beta subunits: anything but auxiliary". Neuroscientist. 7 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1177/107385840100700108. PMID 11486343.

- ↑ Shah BS, Rush AM, Liu S, Tyrrell L, Black JA, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG (August 2004). "Contactin associates with sodium channel Nav1.3 in native tissues and increases channel density at the cell surface". J. Neurosci. 24 (33): 7387–99. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0322-04.2004. PMID 15317864.

- ↑ Wittmack EK, Rush AM, Craner MJ, Goldfarb M, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD (July 2004). "Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 2B: association with Nav1.6 and selective colocalization at nodes of Ranvier of dorsal root axons". J. Neurosci. 24 (30): 6765–75. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1628-04.2004. PMID 15282281.

- ↑ Rush AM, Wittmack EK, Tyrrell L, Black JA, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG (May 2006). "Differential modulation of sodium channel Na(v)1.6 by two members of the fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 2 subfamily". Eur. J. Neurosci. 23 (10): 2551–62. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04789.x. PMID 16817858.

- ↑ Kazarinova-Noyes K, Malhotra JD, McEwen DP, Mattei LN, Berglund EO, Ranscht B, Levinson SR, Schachner M, Shrager P, Isom LL, Xiao ZC (October 2001). "Contactin associates with Na+ channels and increases their functional expression". J. Neurosci. 21 (19): 7517–25. PMID 11567041.

- ↑ Srinivasan J, Schachner M, Catterall WA (December 1998). "Interaction of voltage-gated sodium channels with the extracellular matrix molecules tenascin-C and tenascin-R". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (26): 15753–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15753. PMC 28116

. PMID 9861042.

. PMID 9861042. - ↑ Kim DY, Ingano LA, Carey BW, Pettingell WH, Kovacs DM (June 2005). "Presenilin/gamma-secretase-mediated cleavage of the voltage-gated sodium channel beta2-subunit regulates cell adhesion and migration". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (24): 23251–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.M412938200. PMID 15833746.

- ↑ Ratcliffe CF, Westenbroek RE, Curtis R, Catterall WA (July 2001). "Sodium channel beta1 and beta3 subunits associate with neurofascin through their extracellular immunoglobulin-like domain". J. Cell Biol. 154 (2): 427–34. doi:10.1083/jcb.200102086. PMC 2150779

. PMID 11470829.

. PMID 11470829. - ↑ Grolleau F, Stankiewicz M, Birinyi-Strachan L, Wang XH, Nicholson GM, Pelhate M, Lapied B (2001). "Electrophysiological analysis of the neurotoxic action of a funnel-web spider toxin, delta-atracotoxin-HV1a, on insect voltage-gated Na+ channels". J. Exp. Biol. 204 (Pt 4): 711–21. PMID 11171353.

- ↑ Possani LD, Becerril B, Delepierre M, Tytgat J (September 1999). "Scorpion toxins specific for Na+-channels". Eur. J. Biochem. 264 (2): 287–300. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00625.x. PMID 10491073.

External links

- Sodium Channels at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels". IUPHAR Database of Receptors and Ion Channels. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology.