Volkstaat

"Volkstaat" (an Afrikaans word meaning "people's state", literally "people-state") is a term used to describe proposals to establish self-determination for Afrikaners in South Africa, either on federal principles or as a fully independent Afrikaner homeland.

Following the Great Trek of the 1830s and 1840s, Afrikaner or Boer pioneers expressed a drive for self-determination and independence through the establishment of several Boer republics over the rest of the 19th century. The end of apartheid and the establishment of universal suffrage in South Africa in 1994 left some Afrikaners feeling disillusioned and marginalised by the political changes, and resulted in a proposal for an autonomous Volkstaat.

Several different methods have been proposed for the establishment of a Volkstaat. Besides the use of force, the South African Constitution and international law present certain possibilities for establishment.[2] The geographic dispersal of minority Afrikaner communities throughout South Africa presents a significant obstacle to the establishment of a Volkstaat, as Afrikaners do not form a majority in any separate geographic area that could be sustainable independently. Supporters of the proposal have established three land cooperatives, Orania in the Northern Cape, Kleinfontein in Gauteng, and Balmoral in Mpumalanga, as attempted practical implementations of the idea.

History

Historically, Boers have exhibited a drive for independence which resulted in the establishment of different republics in what is now the modern Republic of South Africa. The Voortrekkers proclaimed separate independent republics, most notably Natalia Republic, the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (the Transvaal). However, after the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), British rule led to the dissolution of the last two remaining Boer states (the Orange Free State and the South African Republic).

Under apartheid, the South African government promoted Afrikaner culture, Afrikaans and English were the official languages, and the majority of the politicians running the country were Afrikaners. The underlying principle of apartheid was racial separatism, and the means by which this was implemented, such as the homeland system of bantustans, were extremely biased against the non-European majority as they excluded them from exercising their rights in the broader South Africa. Afrikaners held a privileged position in South African society, alongside the other Europeans.

In the 1980s, a group of right-wing Afrikaners, led by HF Verwoerd's son-in-law, formed a group called the Oranjewerkers. They also planned a community based on "Afrikaner self-determination", and attempted to create a neo-"boerstaat" (literally: "Farmer State," a reference to an idiomatic term for an Afrikaner-only state) in the remote Eastern Transvaal (now Mpumalanga) community of Morgenzon.[3]

In 1988 Professor Carel Boshoff (1927-2011) founded the Afrikaner-Vryheidstigting (Afrikaner Freedom Foundation), or Avstig. Avstig proposed a Volkstaat in the Northern Cape province, in a largely rural and minimally developed region. Avstig bought the town of Orania in 1991, and turned it into a model Volkstaat. Boshoff continued to be a representative of the Freedom Front, a political party advocating the Volkstaat concept.[4] Orania lies at the far eastern apex of the original Volkstaat state, near where the boundaries of the three provinces Northern Cape, Eastern Cape, and Free State meet.

Support and opposition

The Freedom Front in the 1994 general election

During the 1994 general election, Afrikaners were asked by the Freedom Front (FF) to vote for the party if they wished to form an independent state or Volkstaat for Afrikaners. The results of the election showed that the Freedom Front had the support of 424,555 voters, the fourth highest in the country.[5] The FF did not however gain a majority in any of South Africa's voting districts, their closest being 4,692 votes in Phalaborwa, representing 30.38% of that district.[5]

Public opinion surveys of white South Africans

Two surveys were conducted among white South Africans, in 1993 and 1996, asking the question "How do you feel about demarcating an area for Afrikaners and other "European" South Africans in which they may enjoy self determination? Do you support the idea of a Volkstaat?" The 1993 survey found that 29% supported the idea, and a further 18% would consider moving to a Volkstaat. The 1996 survey found that this had decreased to 22% supporting the idea, and only 9% wanting to move to a Volkstaat. In the second survey, the proportion of white South Africans opposed to the idea had increased from 34% to 66%.[6]

The 1996 survey found that "those who in 1996 said that they would consider moving to a Volkstaat are mainly Afrikaans speaking males, who are supporters of the Conservative Party or Afrikaner Freedom Front, hold racist views (24%; slightly racist: 6%, non racist: 0%), call themselves Afrikaners and are not content with the new democratic South Africa."[6] The study used the Duckitt scale of subtle racism to measure racist views.[6][7]

A 1999 pre-election survey suggested that the 26.9% of Afrikaners wanting to emigrate, but unable to, represented a desire for a solution such as a Volkstaat.[8]

In January 2010, Beeld, an Afrikaans newspaper, held an online survey. Out of 11019 respondents, 56% (6178) said that they would move to a Volkstaat if one were created, a further 17% (1908) would consider it while only 27% (2933) would not consider it as a viable option.[9] The newspaper's analysis of this was that the idea of a Volkstaat was doodgebore (stillborn) and that its advocates had been doing nothing but tread water for the past two decades, although it did suggest that the poll was a measure of dissatisfaction among Afrikaners. Hermann Giliomee later cited the Beeld poll in saying that over half of "northern Afrikaners" would prefer to live in a homeland.[10]

Matters creating support

Dissatisfaction with life in post-apartheid South Africa is often cited as an indication of support for the idea of a Volkstaat among Afrikaners.[11][12] A poll carried out by the Volkstaat Council among white people in Pretoria identified crime, economic problems, personal security, affirmative action, educational standards, population growth, health services, language and cultural rights, and housing as reasons to support the creation of Volkstaat.[11]

Crime

Crime has become a major problem in South Africa since the end of Apartheid. According to a survey for the period 1998 - 2000 compiled by the United Nations, South Africa was ranked second for assault and murder (by all means) per capita.[13] Total crime per capita is 10th out of the 60 countries in the data set. Crime has had a pronounced effect on society: many wealthier South Africans moved into gated communities, abandoning the central business districts of some cities for the relative security of suburbs.

Farm attacks

Among rural Afrikaners, violent crime committed against the white farming community has contributed significantly to a hardening of attitudes. Between 1998 and 2001 there were some 3,500 recorded farm attacks in South Africa, resulting in the murder of 541 farmers, their families or their workers, during only three years. On average more than two farm attack related murders are committed every week.[4]

The Freedom Front interprets this as racial violence targeting Afrikaner: In mid-2001 the Freedom Front appealed to the United Nations Human Rights Commission to place pressure on the South African government to do something about the murder of white South African farmers, which "had taken on the shape of an ethnic massacre". Freedom Front leader Pieter Mulder claimed that most farm attacks seemed orchestrated, and that the motive for the attacks was not only criminal; Mulder further claimed that "a definite anti-Boer climate had taken root in South Africa. People accused of murdering Boers and Afrikaners were often applauded by supporters during court appearances".[4]

The independent Committee of Inquiry into Farm Attacks, appointed by the National Commissioner of Police, published a report in 2003, however, indicating that European people were not targeted exclusively, that theft occurred in most attacks, and that the proportion of European victims had decreased in the four years preceding the report.[14]

In 2010, several international news publications reported that over 3,000 white farmers had been murdered since 1994.[15] This reportage was increased when the far-right political figure Eugene Terre'Blanche was murdered on his farm.[16]

Rise in unemployment

Despite a deterioration of the situation since the end of apartheid, Afrikaners have one of the highest rates of employment, and of job satisfaction, in the country. White unemployment has experienced the greatest proportional increase between 1995 and 2001: 19.7% compared to a national average of 27%. In 2001 some 228,000 economically active whites were unemployed.[4]

Job satisfaction among employed Afrikaners is second to that of English-speaking Europeans, with a survey in 2001 showing that 78% of Afrikaner respondents were either "very satisfied", or "fairly satisfied", with their employment situation.[17] This is worse than the situation under apartheid, when all whites were afforded preferential treatment in non-bantustans; hence, it is likely that those Afrikaners who are unemployed will tend to support initiatives such as the Volkstaat. In Wingard's words, "They will be easy meat for activists."[12]

One in five white South Africans emigrated during the decade ending 2005 due to crime and Affirmative Action.[18] Affirmative Action is implemented by South African legislation, according to which all business employees should reflect the total demographic make up of the country, placing significant difficulty on White-Africans to enter the job market.

Emigration

According to the 1999 pre-election survey, 2.5% of Afrikaner respondents were emigrating, 26.4% would leave if they could, and 5.3% were considering emigrating. The majority, 64.9%, were definitely staying. The survey suggested that the numerous Afrikaners wanting to emigrate, but unable to, represented a desire for a solution such as a Volkstaat.[8]

A survey released by the South African Institute for Race Relations during September 2006, indicated that a decline in South Africa's white population was estimated at 16.1% for the decade ending 2005.[18]

Reduced political representation

The Afrikaners, a minority group in South Africa, relinquished their dominance of the minority rule over South Africa during the 1994 democratic elections and now only play a small role in South African politics. Some Afrikaners, such as the members of the Volkstaat Council,[12] felt that equal representation did not provide adequate protection for minorities, and desired self-rule. The Volkstaat was proposed as one means of achieving this.

Thabo Mbeki, then President of South Africa, quoted an Afrikaner leader with whom he had been engaged in negotiations, "One of our interlocutors expressed this in the following way that 'the Afrikaner is suffering from the hangover of loss of power' resulting in despondency."[11]

Endangered cultural heritage

In 2002 a number of towns and cities with historic Afrikaans names dating back to Voortrekker times—such as Pietersburg and Potgietersrus—had their names changed, often in the face of popular opposition to the change.[4] In the same year the government decided that state departments had to choose a single language for inter- and intra-departmental communication, effectively compelling public servants to communicate using English with one another.[4]

Of the 31 universities in South Africa, five were historically Afrikaans (Free State, Potchefstroom, Pretoria, Rand Afrikaans University and Stellenbosch). In mid-2002 the national Minister of Education, Kader Asmal, announced that Afrikaans medium universities must implement parallel teaching in English, despite a proposal by a government appointed commission that two Afrikaans universities should be retained to further Afrikaans as an academic language. According to the government’s language policy for higher education “the notion of Afrikaans universities runs counter to the end goal of a transformed higher education system".[4]

Movements for the Volkstaat

The Freedom Front has been the major political driving force for the formation of a Volkstaat. This Afrikaner-focused political party has representation in the national Parliament as well as several Provincial legislatures in South Africa. Support for this party has however decreased to just under 140,000 votes, being less than 1% of the total votes cast (approximately 20% among registered Afrikaner voters) by the 2004 national elections. The Freedom Front advocates following the Belgian, Canadian and Spanish models of granting territorial autonomy to linguistic minorities, believing it the only way to protect the rights of Afrikaner people. Under this policy, it proposes the creation of an Afrikaner homeland, comprising the area that lies in the North Western Cape between the West Coast and the Orange River.[19]

The Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging made headlines in March 2008 for their re-activation and plans of establishing an independent Boer state. Plans include a demand for land, such as Stellaland and Goshen, that they claim is legally theirs in terms of the Sand River Convention of 1852 and other historical treaties, through the International Court of Justice in The Hague if necessary.[20]

Die Boeremag (Boer force/power) was a violent Boer separatist organisation. Most of its members were arrested in 2003, and are facing charges of treason.[4] Similar violent methods towards Volkstaat were employed by the Orde van die Dood in the 1980s.[21]

The Front National has called for the re-establishment of Stellaland as possible volkstaat.

Orania and Kleinfontein

One Volkstaat attempt is the small town of Orania in the Northern Cape province. The land on which Orania is built is privately owned, and Afrikaners have been encouraged by promoters of the Volkstaat concept to move to Orania, although only a small number has responded, resulting in a population of approximately 600 in 2001, 10 years after being established. Support for Orania recently seems to be growing somewhat with their recent economic "boom". Today, Orania is home to about 546 Afrikaner families (1,523 inhabitants) but has approximately 10000 'uitwoners' or 'ex'habitants who are part of the Orania Movement.[22][23]

Another attempt is the settlement of Kleinfontein outside Pretoria (in the Tshwane metropolitan area). Both towns fall within larger municipalities, and are not self-governing. Orania is currently petitioning the government to become a separate municipality.[24]

Legal basis

Section 235 of the South African Constitution allows for the right to self-determination of a community, within the framework of "the right of the South African people as a whole to self-determination", and pursuant to national legislation.[25] This section of the constitution was one of the negotiated settlements during the handing over of political power in 1994. The Freedom Front was instrumental in including this section in the constitution. No national legislation in this regard has yet been enacted for any ethnic group, however.

International law presents a recourse for the establishment of a Volkstaat over and above than what the South African Constitution offers. Thus is available to all minorities who wish to obtain self-determination in the form of independence. The requirements set by international law are explained by Prof C. Lloyd Brown-John of the University of Windsor (Canada), as follows: "A minority who are geographically separate and who are distinct ethnically and culturally and who have been placed in a position of subordination may have a right to secede. That right, however, could only be exercised if there is a clear denial of political, linguistic, cultural and religious rights."[26] The rights awarded to minorities were formally asserted by the United Nations General Assembly when it adopted resolution 47/135 on 18 December 1992.[27] However, it is questionable whether this applies to Afrikaners, as there is no municipality in South Africa in which white, Afrikaans-speaking citizens represent a majority,[28] so Afrikaners are not "geographically separate". In addition to this, none of the other rights (political, linguistic, cultural or religious) are being denied.

Governmental response

On 5 June 1998, Mohammed Valli Moosa (then minister of constitutional development in the African National Congress (ANC) government) stated during a parliamentary budget debate that "the ideal of some Afrikaners to develop the North Western Cape as a home for the Afrikaner culture and language within the framework of the Constitution and the charter of human rights is viewed by the government as a legitimate ideal."[29]

Volkstaat Council

The Volkstaat Council was an organisation of 20 people, created by the South African government, via the Volkstaat Council Act in 1994.[30] This was in accordance with sections 184A and 184B of the 1993 South African Constitution, which state: "The Council shall serve as a constitutional mechanism to enable proponents of the idea of a Volkstaat to constitutionally pursue the establishment of such a Volkstaat…".[31] The members, all sympathisers of the volkstaat idea, were: Johann Wingaard, a retired industrialist and chairman of the council, Dirk Viljoen, a town planner (vice-chairman), Anna Boshoff, daughter of Hendrik Verwoerd, her son Carel, the nuclear scientist Wally Grant, Chris de Jager, Mars de Klerk and Hercules Booysen, three jurists, Ernest Pienaar, former general in the South African Defence Force, "Natie" Luyt, Piet Liebenberg, Chris Jooste and Pikkie Robbertze, four academics, Koos Reyneke, an architect, Douw Steyn, a senior member of the civil defence system, Herman Vercueil from the Transvaalse Landbou-unie, Kobus Visser, a former head of the Criminal Investigation Department, Flip Buys, an executive of the trade union Solidariteit, Duncan du Bois, a local politician in Durban and Riaan Visagie, a teacher.[12]

The council's funding was terminated in 1999, without the council being formally disbanded. The council produced a final report, making three key recommendations:[12]

- That areas with an Afrikaner majority should enjoy "territorial self-determination". Areas identified included the region around Pretoria, and a region of the Northern Cape Province.

- That the government establish an "Afrikaner Council", as an advisory board to the government. "Representation in parliament, where numerical power is all that mattered, was not seen as a democratic system for minorities."

- That the government create legislation enacting the other two points. Draft legislation for the Afrikaner Council was provided.

The provisions in the constitution allowing for formation of the council were removed in 2001, by the Repeal of Volkstaat Council Provisions Act, in accordance with the original act.[32]

Johann Wingard, chair of the council, expressed the view in 2005 that he doubted if any government official ever opened any of the reports to read them. Additionally, he stated that only a "civil war" would ever enable Afrikaners to gain independence in any part of South Africa.[12] The opposite is suggested, however, by the fact that then deputy president, Thabo Mbeki, and then Minister of Home Affairs, Dr Mangosuthu Buthelezi, quoted figures from Volkstaat Council reports in a report to parliament in 1999.[11] Nelson Mandela, the president at the time, specially requested that the delivery of the report be delayed until he could attend its presentation personally.

Subsequent to the disbanding of the Volkstaat Council, the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities was established in 2003.[33] This committee is charged with the protection of the rights to cultural identity of all self-identifying groups in South Africa, including Afrikaners. The committee includes an Afrikaner, JCH Landman, who is also a member of the Afrikaner Alliance. The reports from the Volkstaat Council were to be handed over to this committee.[11]

The ANC government formalised their stance on the issue in 1998-1999, when they declared that they would not support a Volkstaat, but would do everything they could to ensure the protection of the Afrikaner language and culture, along with the other minority cultures in the country.[11]

Boer-Afrikaner Volksraad

On 23 July 2014, members of an Afrikaner group who call themselves the "Boer-Afrikaner Volksraad" announced forthcoming talks with the South African government around the concept of territorial self-determination for "Boer Afrikaner people". The talks would include either President Jacob Zuma, his deputy Cyril Ramaphosa, or both; and would be held before the end of August 2014.[34]

See also

References

- ↑ "National Archives of South Africa". Retrieved 2009-05-17.

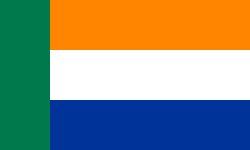

Flag: A rectangular flag, proportion 2:3, consisting of three horizontal stripes of equal width, from top to bottom, orange, white and blue, and at the hoist a vertical green stripe one and one quarter the width of each of the other three stripes.

- ↑ http://www.un.org/en/decolonization/declaration.shtml

- ↑ Du Toit, Brian M. (1991). "The Far Right in Current South African Politics". The Journal of Modern African Studies. Cambridge University Press. 29 (4): 627–67. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00005693. ISSN 1469-7777. JSTOR 161141 – via JSTOR. (registration required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 M. Schönteich; H. Boshoff (2003). "'Volk' Faith and Fatherland, The Security Threat Posed by the White Right". Institute for Security Studies (South Africa). Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- 1 2 Manuel Álvarez-Rivera. "1994 General Election in South Africa". Election Resources on the Internet. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- 1 2 3 G. Theissen (1997). "Between Acknowledgement and Ignorance: How white South Africans have dealt with the apartheid past". Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, University of the Witwatersrand. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ↑ Duckitt, John (1991). "The development and validation of a subtle racism scale in South Africa". South African Journal of Psychology. 21 (4): 233–239.

- 1 2 R. W. Johnson (1999). "How to use that huge majority". Focus. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ Pieter du Toit (12 January 2010). "Volkstaat hou g'n heil in". Beeld. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ↑ Uys, Stanley (16 March 2010). "The Afrikaners are restive". Politicsweb. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mbeki, T. & Buthelezi, M. (24 March 1999). "Report of the Government of the Republic of South Africa on the Question of the Afrikaners". Speech delivered at the National Assembly, South Africa. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Afrikaner Independence: Interview With Volkstaat Council Chair Johann Wingard". 27 May 2005. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "South African Crime Statistics". NationMaster. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "South African Government Committee of Inquiry into Farm Attacks". Institute for Security Studies. 2003. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ White farmers 'being wiped out' Sunday Times. 28 March 2010

- ↑ White supremacist Eugene Terre'Blanche is hacked to death after row with farmworkers The Guardian. 4 April 2010

- ↑ "Race relations and racism in everyday life". Institute of Race Relations. 2001. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- 1 2 "Een miljoen wittes weg uit SA - studie" (in Afrikaans). Rapport. 23 September 2006. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- 1 2 "Freedom Front Policy". Freedom Front. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ Bevan, Stephen (1 June 2008). "AWB leader Terre'Blanche rallies Boers again". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ Carrots and sticks: the TRC and the South African amnesty process. Jeremy Sarkin, Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes. Intersentia nv, 2004. ISBN 90-5095-400-6, ISBN 978-90-5095-400-6. Pg 289.

- ↑ http://www.orania.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/orania-voorgrond-mei-08-finaal.pdf

- ↑ "Orania residents confident of establishing an exclusively white homeland". SABC News. 12 March 2001. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ Groenewald, Y. (1 November 2005). "Orania, white and blue". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "Section 235". South African Constitution. 1996. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ C. Lloyd Brown-John (1997). "Self-determination and separation" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "Resolution 47/135 of 18 December 1992 - Declaration on the Rights of Minorities". United Nations. 1992. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "Census 2001 at a glance". Statistics South Africa. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ↑ "VF se strewe legitiem, sê Moosa" [Minister Valli Moosa views volkstaat as legitimate ideal]. beeld.com. 5 June 1998.

- ↑ "Volkstaat Council Act" (PDF). 1994. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "Chapter 11". Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. 1993. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "Repeal of Volkstaat Council Provisions Act" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "Cultural, religious & linguistic rights". 2003. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "Afrikaner group seeks independent state". News24. 2014-07-23. Retrieved 2014-07-24.