Vojnomir

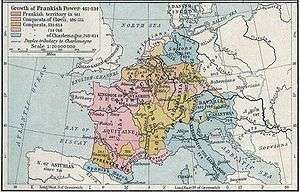

Vojnomir was a Slavic military commander in Frankish service. The Royal Frankish Annals makes mention of a Wonomyrus Sclavus (Vojnomir the Slav) active in 795.[1] Eric of Friuli, sent Vojnomir with his army into Pannonia, between the Danube and Tisza, where they pillaged the Avars' dominions.[1] According to Milko Kos they were not met with serious Avar resistance, and they conquered many forts.[2] The next year the Avars were defeated and Frankish power was extended further east, to the central Danube.[1] Vojnomir's leading position in the campaign has been presumed as very possible with regard to the textual analysis of Annales regni Francorum.[3]

His origin and social position are not mentioned in any contemporary medieval source.[4] His identity has been the subject of several hypotheses;[4] that he was a prince or duke that held lands in either Slavonia, Carniola or Friuli, according to different hypotheses.

Hypotheses

Vojnomir remains an enigmatic historical personality. Even the correct reading of his name is unclear. Instead of Vojnomir the original Wonomyro (Uuonomiro, Uuonomyro) could also be read as Zvonimir, just like the name of Croat king Demetrius Zvonimir has been corrupted in Svinimiro.[5] Some authors interpret Vojnomir as having been a Croatian duke, a military leader of the Frankish army, or the prince of Carniola.[6] There are three most reliable hypotheses about his origin: the "Pannonian hypothesis", the "Career hypothesis" and the "Carniolan hypothesis".[4][7] At least two explanations could be read in the context of modern nationalistic mythology: Slovene and German authors from the Austrian part of Austria-Hungary are prone to support the Carniolan origin and Croatian authors are prone to support the Pannonian or the Istrian origin.[2][8]

Pannonian hypothesis

According to the Pannonian hypothesis, Vojnomir was a knez (duke or prince) of Slavonia (known in Croatian historiography as "Pannonian Croatia"), from ca. 790 to 800 or from 791 to ca. 810. He is believed to have fought the Pannonian Avars during their occupation of what is today northern Croatia;[9][10][11] according to Francis Dvornik, he launched a joint counterattack with the help of Frankish troops under King Charlemagne in 791, successfully driving the Avars out of Croatia.[12][13][14] In return for the help of Charlemagne, Vojnomir was obliged to recognize the Frankish sovereignty, to convert to Christianity and to have his territory named Pannonian Croatia.[12][13][14]

On Christmas Day in 800, a year after the Siege of Trsat, the Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Imperator Romanorum ("Emperor of the Romans") in Saint Peter's Basilica.[15] Nicephorus I of the Byzantine Empire and Charlemagne of the Holy Roman Empire settle their imperial boundaries in 803.[15] Following these events, known as the Pax Nicephori, the Principality of Dalmatian Croatia peacefully accepted limited Frankish overlordship.[15] Contrary to Dalmatian Croatia, after the death of duke Vojnomir, the former Frankish ally Pannonian Croatia led a resistance to Frankish domination under the leadership of duke Ljudevit Posavski.

Fine Jr. claimed that Vojnomir, a Pannonian Croatian duke, aided Charlemagne's major victory against the Pannonian Avars in 796, after which the Franks were made overlords "over the Croatians of northern Dalmatia, Slavonia and Pannonia".[16]

Career hypothesis

The military hypothesis claims that Vojnomir was only a Slav making a career in the Frankish troops. He was not a ruler.[17] From the only reliable contemporary source, Annales regni Francorum, it is known that Vojnomir was a military leader.[8] His status as a duke or a prince is not mentioned at all. In the past most of the historians described Vojnomir as one of Slavic dukes or princes in the neighbourhood of Friuli. However, according to Peter Štih, it is hard to believe that a leader of a foreign land could be accepted as a Frankish military leader by the Franks; he was probably only an exceptional Slavic individual who made his career in the Frankish army and perhaps he was only a Friulian Slav.[4] According to Nenad Labus, Vojnomir could also have been a military leader from Istria.[5]

Carniolan hypothesis

Many authors interpret Vojnomir as the Prince of Carniola.[6] One of the arguments is that Carniola was the land just between Friuli and Avaria. Frankish troops passed Carniola, so this land is natural candidate for Vojnomir's homeland.[18] Carniolans also hated their Avarian enemies.[2][4] There are claims that the ancestors of the Croats were not the subjects of the Franks at this time.[2] The Carniolans on the other side were already ruled by the Franks from 791 AD with their basic autonomy and the rule of their own domestic princes retained until the rebel of Ljudevit.[2][8] Regarding the subordination of the Croat ancestors it was proved only for the Slavs in Dalmatia, whereas the Pannonian Slavs could have been subjected to the Franks already in the year 791.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 Oto Luthar (2008). The Land Between: A History of Slovenia. Peter Lang. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-3-631-57011-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kos Milko (1902): Gradivo za zgodovino Slovencev v srednjem veku. Ljubljana, Leonova družba. Case 293, pg. 325-327.

- 1 2 Šišić Ferdo (1902). Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara. Zagreb, Nakladni zavod matice Hrvatske. pp. 304-305

- 1 2 3 4 5 Štih 2001, pp. 41-42.

- 1 2 Nenad, Labus (2000): Tko je ubio vojvodu Erika. From: Šanjek Franjo (ur): Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru. Sv. 42. Page. 10.

- 1 2 for example W. Pohl, H. Krahwinkler, R. Bratož, F. Kos, M. Kos, B. Grafenauer. In: Štih, Peter (2001). Ozemlje Slovenije v zgodnjem srednjem veku: Osnovne poteze zgodovinskega razvoja od začetka 6. do konca 9. stoletja. Ljubljana, Filozofska fakulteta. Page 41-42; and in: Grafenauer Bogo: Vojnomir

- ↑ Voje, Ignacij(1994). Nemirni Balkan: Zgodovinski pregled od 6. Do 18. Stoletja. Ljubljana, DZS. Page 47.

- 1 2 3 Grafenauer Bogo: Vojnomir Archived August 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Milos M. Vujnovich (1974). Yugoslavs in Louisiana. Pelican Publishing. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-1-4556-1455-4.

- ↑ Lister M. Matheson (2012). Icons of the Middle Ages: Rulers, Writers, Rebels, and Saints. ABC-CLIO. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-0-313-34080-2.

- ↑ Peter Heather (4 March 2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 533–. ISBN 978-0-19-975272-0.

- 1 2 Dvornik, Francis (1956). The Slavs. American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- 1 2 Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1342-4.

- 1 2 Wiet, Gaston (1975). The Great Medieval Civilizations. Allen and Unwin.

- 1 2 3 Klaić, Vjekoslav (1985). Povijest Hrvata: Knjiga Prva (in Croatian). Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9788640100519.

- ↑ Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The early medieval Balkans: a critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century. University of Michigan Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- ↑ Corpus testimoniorum vetustissimorum ad historiam slavicam pertinentium. Издательская фирма "Восточная лит-ра" РАН. 1995.

По мнению В.Поля, Вономир не был самостоятельным правителем, а был лишь славянским выходцем на службе у франков: «славянскому „племенному князю" Эрик, вероятно, не дал бы так легко своих людей в подчинение, ...

- ↑ Kos Milko (1933). Zgodovina Slovencev od naselitve do reformacije. Ljubljana, Jugoslovanska knjigarna. Str. 64.

Sources

- Peter Štih (2001). Ozemlje Slovenije v zgodnjem srednjem veku: osnovne poteze zgodovinskega razvoja od začetka 6. do konca 9. stoletja. Filozofska Fakulteta, Oddelek za Zgodovino. ISBN 978-961-227-084-1.

- Milko Kos (1960). Istorija Slovenaca od doseljenja do petnaestog veka. Prosveta.