Multivitamin

A multivitamin is a preparation intended to be a dietary supplement with vitamins, dietary minerals, and other nutritional elements. Such preparations are available in the form of tablets, capsules, pastilles, powders, liquids, and injectable formulations. Other than injectable formulations, which are only available and administered under medical supervision, multivitamins are recognized by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (the United Nations' authority on food standards) as a category of food.[1]

Multivitamin supplements are commonly provided in combination with dietary minerals. A multivitamin/mineral supplement is defined in the United States as a supplement containing 3 or more vitamins and minerals that does not include herbs, hormones, or drugs, where each vitamin and mineral is included at a dose below the tolerable upper level, as determined by the Food and Drug Board, and does not present a risk of adverse health effects.[2] The terms multivitamin and multimineral are often used interchangeably. There is no scientific definition for either.[3]

In otherwise healthy people, some scientific evidence indicates that multivitamin supplements do not prevent cancer, heart disease, or other ailments. However, there may be specific groups of people who may benefit from multivitamin supplements (for example, people with poor nutrition or at high risk of macular degeneration).[4][5]

Products and components

Many multivitamin formulas contain vitamin C, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, B12, biotin, A, E, D2 (or D3), K, potassium, iodine, selenium, borate, zinc, calcium, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, betacarotene, and/or iron. Multivitamins are typically available in a variety of formulas based on age and sex, or (as in prenatal vitamins) based on more specific nutritional needs; a multivitamin for men might include less iron, while a multivitamin for seniors might include extra vitamin D. Some formulas make a point of including extra antioxidants. "High-potency formulas" include at least two-thirds of the nutrients called for by recommended dietary allowances. Some nutrients, such as calcium and magnesium, are rarely included at 100% of the recommended allowance because the pill would become too large. Most multivitamins come in capsule form; tablets, powders, chewables, liquids, and injectable formulations also exist. In the U.S., the FDA requires any product marketed as a "multivitamin" to contain at least three vitamins and minerals; furthermore, the dosages must be below a "tolerable upper limit", and a multivitamin and may not include herbs, hormones, or drugs.[6]

Uses

For certain people, particularly the elderly, supplementing the diet with additional vitamins and minerals can have health impacts, however the majority will not benefit.[7] People with dietary imbalances may include those on restrictive diets and those who cannot or will not eat a nutritious diet. Pregnant women and elderly adults have different nutritional needs than other adults, and a multivitamin may be indicated by a physician. Generally, medical advice is to avoid multivitamins, particularly those containing vitamin A, during pregnancy unless they are recommended by a health care professional. However, the NHS recommends 10μg of Vitamin D per day throughout the pregnancy and whilst breast feeding, as well as 400μg of folic acid during the first trimester (first 12 weeks of pregnancy).[8] Some individuals may need to take iron, vitamin C, or calcium supplements during pregnancy, but only on the advice of a doctor.

In the 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 52% of adults in the United States reported taking at least one dietary supplement in the last month and 35% reported regular use of multivitamin-multimineral supplements. Women versus men, older adults versus younger adults, non-Hispanic whites versus non-Hispanic blacks, and those with higher education levels versus lower education levels (among other categories) were more likely to take multivitamins. Individuals who use dietary supplements (including multivitamins) generally report higher dietary nutrient intakes and healthier diets. Additionally, adults with a history of prostate and breast cancers were more likely to use dietary and multivitamin supplements.[9]

Precautions

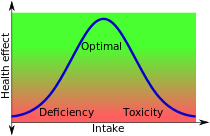

The amounts of each vitamin type in multivitamin formulations are generally adapted to correlate with what is believed to result in optimal health effects in large population groups.

The health benefit of vitamins generally follows a biphasic dose-response curve, taking the shape of a bell curve, with the area in the middle being the safe-intake range and the edges representing deficiency and toxicity.[10] For example, the Food and Drug Administration recommends that adults on a 2,000 calorie diet get between 60 and 90 milligrams of vitamin C per day.[11] This is the middle of the bell curve. The upper limit is 2,000 milligrams per day for adults, which is considered potentially dangerous.[12]

However, these standard amounts may not correlate what is optimal in certain subpopulations, such as in children, pregnant women and people with certain medical conditions and medication.

In particular, pregnant women should generally consult their doctors before taking any multivitamins: for example, either an excess or deficiency of vitamin A can cause birth defects.[13] Long-term use of beta-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E supplements may shorten life,[media 1][14] and increase the risk of lung cancer in people who smoke (especially those smoking more than 20 cigarettes per day), former smokers, people exposed to asbestos, and those who use alcohol . Many common brand supplements in the United States contain levels above the DRI/RDA amounts for some vitamins or minerals.

Severe vitamin and mineral deficiencies require medical treatment and can be very difficult to treat with common over-the-counter multivitamins. In such situations, special vitamin or mineral forms with much higher potencies are available, either as individual components or as specialized formulations.

Multivitamins in large quantities may pose a risk of an acute overdose due to the toxicity of some components, principally iron. However, in contrast to iron tablets, which can be lethal to children,[15] toxicity from overdoses of multivitamins are very rare.[16] There appears to be little risk to supplement users of experiencing acute side effects due to excessive intakes of micronutrients.[17] There also are strict limits on the retinol content for vitamin A during pregnancies that are specifically addressed by prenatal formulas.

As noted in dietary guidelines from Harvard School of Public Health in 2008, multivitamins should not replace healthy eating, or make up for unhealthy eating.[18] In 2015, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force analyzed studies that included data for about 450,000 people. The analysis found no clear evidence that multivitamins prevent cancer or heart disease, helped people live longer, or "made them healthier in any way."[19]

Research

Provided that precautions are taken (such as adjusting the vitamin amounts to what is believed to be appropriate for children, pregnant women or people with certain medical conditions), multivitamin intake is generally safe, but research is still ongoing with regard to what health effects multivitamins have.

Evidence of health effects of multivitamins comes largely from prospective cohort studies which evaluate health differences between groups that take multivitamins and groups that do not. Correlations between multivitamin intake and health found by such studies may not result from multivitamins themselves, but may reflect underlying characteristics of multivitamin-takers. For example, it has been suggested that multivitamin-takers may, overall, have more underlying diseases (making multivitamins appear as less beneficial in prospective cohort studies).[20] On the other hand, it has also been suggested that multivitamin users may, overall, be more health-conscious (making multivitamins appear as more beneficial in prospective cohort studies).[21][22] Randomized controlled studies have been encouraged to address this uncertainty.[23]

Cohort studies

In February 2009, a study conducted in 161,808 postmenopausal women from the Women's Health Initiative clinical trials concluded that after eight years of follow-up "multivitamin use has little or no influence on the risk of common cancers, cardiovascular disease, or total mortality".[24] Another 2010 study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology suggested that multivitamin use during chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer had no effect on the outcomes of treatment.[25] A very large prospective cohort study published in 2011, including more than 180,000 participants, found no significant association between multivitamin use and mortality from all causes. The study also found no impact of multivitamin use on the risk of cardiovascular disease or cancer.[26]

A cohort study that received widespread media attention[27][28] is the Physicians' Health Study II (PHS-II).[29] PHS-II was a double-blind study of 14,641 male U.S. physicians initially aged 50 years or older (mean age of 64.3) that ran from 1997 to June 1, 2011. The mean time that the men were followed was 11 years. The study compared total cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) for participants taking a daily multivitamin (Centrum Silver by Pfizer) versus a placebo. Compared with the placebo, men taking a daily multivitamin had a small but statistically significant reduction in their total incidence of cancer. In absolute terms the difference was just 1.3 cancer diagnoses per 1000 years of life. The hazard ratio for cancer diagnosis was 0.92 with a 95% confidence interval spanning 0.86 - 0.998 (P = .04), this implies a benefit of between 14% and .2% over placebo in the confidence interval. No statistically significant effects were found for any specific cancers or for cancer mortality. As pointed out in an editorial in the same issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, the investigators observed no difference in the effect whether the study participants were or were not adherent to the multivitamin intervention, which diminishes the dose–response relationship.[30] The same editorial argued that the study did not properly address the multiple comparisons problem, in that the authors neglected to fully analyze all 28 possible associations in the study—they argue if this had been done the statistical significance of the results would be lost.[30]

Using the same PHS-II study researchers concluded that taking a daily multivitamin did not have any effect in reducing heart attacks and other major cardiovascular events, MI, stroke, and CVD mortality.[31]

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

One major meta-analysis published in 2011, including previous cohort and case-control studies, concluded that multivitamin use was not significantly associated with the risk of breast cancer. It noted that one Swedish cohort study has indicated such an effect, but with all studies taken together, the association was not statistically significant.[23] A 2012 meta-analysis of ten randomized, placebo-controlled trials published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease found that a daily multivitamin may improve immediate recall memory, but did not affect any other measure of cognitive function.[32]

Another meta-analysis, published in 2013, found that multivitamin-multimineral treatment "has no effect on mortality risk,"[33] and a 2013 systematic review found that multivitamin supplementation did not increase mortality and might slightly decrease it.[34] A 2014 meta-analysis reported that there was "sufficient evidence to support the role of dietary multivitamin/mineral supplements for the decreasing the risk of age-related cataracts."[35] A 2015 meta-analysis argued that the positive result regarding the effect of vitamins on cancer incidence found in Physicians' Health Study II (discussed above) should not be overlooked despite the neutral results found in other studies.[36]

Expert bodies

A 2006 report by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality concluded that "regular supplementation with a single nutrient or a mixture of nutrients for years has no significant benefits in the primary prevention of cancer, cardiovascular disease, cataract, age-related macular degeneration or cognitive decline."[4] However, the report noted that multivitamins have beneficial effects for certain sub-populations, such as people with poor nutritional status, that vitamin D and calcium can help prevent fractures in older people, and that zinc and antioxidants can help prevent age-related macular degeneration in high-risk individuals.[4]

A Cochrane Review on the specific topic of age-related macular degeneration found that "taking vitamin E or beta-carotene supplements will not prevent or delay the onset of age-related macular degeneration."[37]

According to the Harvard School of Public Health: "...many people don’t eat the healthiest of diets. That’s why a multivitamin can help fill in the gaps, and may have added health benefits."[38]

The U.S. Office of Dietary Supplements, a branch of the National Institutes of Health, suggests that multivitamin supplements might be helpful for some people with specific health problems (for example, macular degeneration). However, the Office concluded that "most research shows that healthy people who take an MVM [multivitamin] do not have a lower chance of diseases, such as cancer, heart disease, or diabetes. Based on current research, it's not possible to recommend for or against the use of MVMs to stay healthier longer."[5]

The United Kingdom Food Standards Agency recommended in 2007 that pregnant women should take extra folic acid and iron and that older people might need extra vitamin D and iron.[39] However, these recommendations also advised that "vitamin and mineral supplements are not a replacement for good eating habits."[39]

Regulations

United States

Because of their categorization as a dietary supplement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), most multivitamins sold in the U.S. are not required to undergo the testing procedures typical of pharmaceutical drugs.

However, some multivitamins contain very high doses of one or several vitamins or minerals, or are specifically intended to treat, cure, or prevent disease, and therefore require a prescription or medicinal license in the U.S. Since such drugs contain no new substances, they do not require the same testing as would be required by a New Drug Application, but were allowed on the market as drugs due to the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation program.[40]

See also

References

- ↑ Codex Guidelines for Vitamin and Mineral Food Supplements Accessed 27 December 2007

- ↑ National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Panel. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: multivitamin/mineral supplements and chronic disease prevention" Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:257S-64S

- ↑ Accessed 21 July 2009

- 1 2 3 Huang HY, Caballero B, Chang S, et al. (May 2006). "Multivitamin/mineral supplements and prevention of chronic disease" (PDF). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) (139): 1–117. PMID 17764205.

- 1 2 "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Multivitamin/mineral Supplements". Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ↑ "How to Choose a Multivitamin Supplement". WebMD. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ Dietary supplements: Using vitamin and mineral supplements wisely, Mayo Clinic

- ↑ National Health Service. "Vitamins and nutrition in pregnancy". NHS Choices. NHS. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Rock, Cheryl L (2007). "Multivitamin-multimineral supplements: who uses them?". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 85 (1): 277S–279S.

- ↑ Combs, Jr., G. F. (1998). The vitamins: Fundamental aspects in nutrition and health. Academic Press: San Diego, CA.

- ↑ "Council for Responsible Nutrition". Crnusa.org. http://www.crnusa.org/about_recs4.html. Retrieved 2011-03-30.

- ↑ MedlinePlus. (2010). "Vitamin C (Ascorbic acid)"

- ↑ Collins MD, Mao GE (1999). "Teratology of retinoids". Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 39: 399–430. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.399. PMID 10331090.

- ↑ Bjelakovic, G.; D. Nikolova; LL Gluud; RG Simonetti; C. Gluud (April 2008). Bjelakovic, Goran, ed. "Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 (2): CD007176. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007176. PMID 18425980.

- ↑ Cheney K, Gumbiner C, Benson B, Tenenbein M (1995). "Survival after a severe iron poisoning treated with intermittent infusions of deferoxamine". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 33 (1): 61–6. doi:10.3109/15563659509020217. PMID 7837315.

- ↑ Linakis JG, Lacouture PG, Woolf A (December 1992). "Iron absorption from chewable vitamins with iron versus iron tablets: implications for toxicity". Pediatr Emerg Care. 8 (6): 321–4. doi:10.1097/00006565-199212000-00003. PMID 1454637.

- ↑ Kiely M, Flynn A, Harrington KE, et al. (October 2001). "The efficacy and safety of nutritional supplement use in a representative sample of adults in the North/South Ireland Food Consumption Survey". Public Health Nutr. 4 (5A): 1089–97. doi:10.1079/PHN2001190. PMID 11820922.

- ↑ Harvard School of Public Health (2008). Food pyramids: What should you really eat?. Retrieved from http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource[]

- ↑ "Why You Don't Need A Multivitamin - Consumer Reports". Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- ↑ Li, K.; Kaaks, R.; Linseisen, J.; Rohrmann, S. (2011). "Vitamin/mineral supplementation and cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in a German prospective cohort (EPIC-Heidelberg)". European Journal of Nutrition. 51 (4): 407–13. doi:10.1007/s00394-011-0224-1. PMID 21779961.

- ↑ Seddon, J. M.; Christen, W. G.; Manson, J. E.; Lamotte, F. S.; Glynn, R. J.; Buring, J. E.; Hennekens, C. H. (1994). "The use of vitamin supplements and the risk of cataract among US male physicians". American Journal of Public Health. 84 (5): 788–792. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.5.788. PMC 1615060

. PMID 8179050.

. PMID 8179050. - ↑ Neuhouser ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Thomson C, et al. (February 2009). "Multivitamin use and risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease in the Women's Health Initiative cohorts". Arch. Intern. Med. 169 (3): 294–304. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.540. PMID 19204221.

- 1 2 Chan AL, Leung HW, Wang SF (April 2011). "Multivitamin supplement use and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis". Ann Pharmacother. 45 (4): 476–84. doi:10.1345/aph.1P445. PMID 21487086.

- ↑ Neuhouser ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Thomson C, et al. (2009). "Multivitamin use and risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease in the Women's Health Initiative cohorts". Arch Intern Med. 169 (3): 294–304. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.540. PMID 19204221.

- ↑ Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Chan JA, et al. (October 2010). "Multivitamin use is not associated with cancer recurrence or survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803". J. Clin. Oncol. 28 (28): 4354–63. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0362. PMC 2954134

. PMID 20805450.

. PMID 20805450. - ↑ Park SY, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN (April 2011). "Multivitamin use and the risk of mortality and cancer incidence: the multiethnic cohort study". Am. J. Epidemiol. 173 (8): 906–14. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq447. PMC 3105257

. PMID 21343248.

. PMID 21343248. - ↑ Rabin, Roni Caryn (October 17, 2012). "Daily Multivitamin May Reduce Cancer Risk, Clinical Trial Finds". New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ↑ Winslow, Ron (18 October 2012). "Multivitamin Cuts Cancer Risk, Large Study Finds". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Gaziano, J. Michael; Sesso, Howard D.; Christen, William G.; Bubes, Vadim; Smith, Joanne P.; MacFadyen, Jean; Schvartz, Miriam; Manson, JoAnn E.; Glynn, Robert J.; Buring, Julie E. (October 17, 2012). "Multivitamins in the Prevention of Cancer in Men - The Physicians' Health Study II Randomized Controlled Trial". JAMA. 308 (18): 1871–80. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14641. PMC 3517179

. PMID 23162860. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

. PMID 23162860. Retrieved October 17, 2012. - 1 2 Bach, Peter B.; Lewis, Roger, J. (14 November 2012). "Multiplicities in the Assessment of Multiple Vitamins Is It Too Soon to Tell Men That Vitamins Prevent Cancer?". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 308 (18): 1916–1917. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.53273. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Sesso, Howard D.; Christen, William G.; Bubes, Vadim; Smith, Joanne P.; MacFadyen, Jean; Schvartz, Miriam; Manson, JoAnn E.; Glynn, Robert J.; Buring, Julie E.; Gaziano, J. Michael (November 7, 2012). "Multivitamins in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Men - The Physicians' Health Study II Randomized Controlled Trial". JAMA. 308: 1751. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14805. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ↑ The Effects of Multivitamins on Cognitive Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 10.3233/JAD-2011-111751. Published 13 February 2012. Accessed 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Macpherson H, Pipingas A, Pase MP (February 2013). "Multivitamin-multimineral supplementation and mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97 (2): 437–44. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.049304. PMID 23255568.

- ↑ Alexander, DD; Weed, DL; Chang, ET; Miller, PE; Mohamed, MA; Elkayam, L (2013). "A systematic review of multivitamin-multimineral use and cardiovascular disease and cancer incidence and total mortality.". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 32 (5): 339–54. doi:10.1080/07315724.2013.839909. PMID 24219377.

- ↑ Zhao, Li-Quan; Li, Liang-Mao; Zhu, Huang; The Epidemiological Evidence-Based Eye Disease Study Research Group (28 February 2014). "The Effect of Multivitamin/Mineral Supplements on Age-Related Cataracts: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 6 (3): 931–949. doi:10.3390/nu6030931.

- ↑ Angelo, G; Drake, VJ; Frei, B (18 June 2014). "Efficacy of multivitamin/mineral supplementation to reduce chronic disease risk: a critical review of the evidence from observational studies and randomized controlled trials.". Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 55: 0. doi:10.1080/10408398.2014.912199. PMID 24941429.

- ↑ Evans, JR; Lawrenson, JG (Jun 13, 2012). "Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age-related macular degeneration.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 6: CD000253. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000253.pub3. PMID 22696317.

- ↑ http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/vitamins/

- 1 2 The Balance of Good Health Food Standards Agency, Accessed 31 May 2008

- ↑ See 36 Fed. Reg. 6843 (Apr. 9, 1971).

News media reporting

- ↑ Randerson J. "Vitamin supplements may increase risk of death", The Guardian, April 16, 2008. Cochrane Collaboration author, Goran Bjelakovic's opinion: The bottom line is, current evidence does not support the use of antioxidant supplements in the general healthy population or in patients with certain diseases.

External links

- Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Multivitamin/mineral Supplements, from the U.S. National Institutes of Health

- Multivitamin/Mineral Supplements, from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- Multivitamins and cancer, from the American Cancer Society

- Safe upper levels for vitamins and minerals - Report of the UK Food Standards Agency Expert Group on Vitamins and Minerals