Victorian literature

While in the preceding Romantic period poetry had been the dominant genre, it was the novel that was most important in the Victorian period. Charles Dickens (1812–1870) dominated the first part of Victoria's reign: his first novel, Pickwick Papers, was published in 1836, and his last Our Mutual Friend between 1864–5. William Thackeray's (1811–1863) most famous work Vanity Fair appeared in 1848, and the three Brontë sisters, Charlotte (1816–55), Emily (1818–48) and Anne (1820–49), also published significant works in the 1840s. A major later novel was George Eliot's (1819–80) Middlemarch (1872), while the major novelist of the later part of Queen Victoria's reign was Thomas Hardy (1840–1928), whose first novel, Under the Greenwood Tree, appeared in 1872 and his last, Jude the Obscure, in 1895.

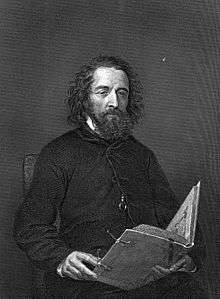

Robert Browning (1812–89) and Alfred Tennyson (1809–92) were Victorian England's most famous poets, though more recent taste has tended to prefer the poetry of Thomas Hardy, who, though he wrote poetry throughout his life, did not publish a collection until 1898, as well as that of Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–89), whose poetry was published posthumously in 1918. Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909) is also considered an important literary figure of the period, especially his poems and critical writings. Early poetry of W. B. Yeats was also published in Victoria's reign. With regard to the theatre it was not until the last decades of the nineteenth century that any significant works were produced. This began with Gilbert and Sullivan's comic operas, from the 1870s, various plays of George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) in the 1890s, and Oscar Wilde's (1854–1900) The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895.

Prose fiction

Charles Dickens is the most famous Victorian novelist. Extraordinarily popular in his day with his characters taking on a life of their own beyond the page; Dickens is still one of the most popular and read authors of that time period. His first novel, The Pickwick Papers (1836), written when he was twenty-five, was an overnight success, and all his subsequent works sold extremely well. The comedy of his first novel has a satirical edge and this pervades his writing. Dickens worked diligently and prolifically to produce the entertaining writing that the public wanted, but also to offer commentary on social problems and the plight of the poor and oppressed. His most important works include "Oliver Twist" (1837–1838), "A Christmas Carol" (1843), "Dombey and Son" (1846–1848), "David Copperfield" (1848 - 1850), "Bleak House" (1852 - 1853), "Little Dorrit" (1855 - 1857), "A Tale of Two Cities" (1858 - 1859), and "Great Expectations" (1860 -1861).There is a gradual trend in his fiction towards darker themes which mirrors a tendency in much of the writing of the 19th century.

William Thackeray was Dickens' great rival in the first half of Queen Victoria's reign. With a similar style but a slightly more detached, acerbic and barbed satirical view of his characters, he also tended to depict a more middle class society than Dickens did. He is best known for his novel Vanity Fair (1848), subtitled A Novel without a Hero, which is an example of a form popular in Victorian literature: a historical novel in which recent history is depicted.

Anne, Charlotte and Emily Brontë produced notable works of the period, although these were not immediately appreciated by Victorian critics. Wuthering Heights (1847), Emily's only work, is an example of Gothic Romanticism from a woman's point of view, which examines class, myth, and gender. Jane Eyre (1847), by her sister Charlotte, is another major nineteenth century novel that has gothic themes. Anne's second novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848), written in realistic rather than romantic style, is mainly considered to be the first sustained feminist novel.[1]

Later in this period George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), published The Mill on the Floss in 1860, and in 1872 her most famous work Middlemarch. Like the Brontës she published under a masculine pseudonym.

In the later decades of the Victorian era Thomas Hardy was the most important novelist. His works include Under the Greenwood Tree (1872), Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), Tess of the d'Urbervilles (1891), and Jude the Obscure (1895).

Other significant novelists of this era were Elizabeth Gaskell (1810–1865), Anthony Trollope (1815–1882), George Meredith (1828–1909), and George Gissing (1857–1903).

Poetry

The husband and wife team of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning conducted their love affair through verse and produced many tender and passionate poems. Both Matthew Arnold and Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote poems which sit somewhere in between the exultation of nature of the romantic Poetry and the Georgian Poetry of the early 20th century. However Hopkins's poetry was not published until 1918. Arnold's works anticipate some of the themes of these later poets, while Hopkins drew inspiration from verse forms of Old English poetry such as Beowulf.

The reclaiming of the past was a major part of Victorian literature with an interest in both classical literature but also the medieval literature of England. The Victorians loved the heroic, chivalrous stories of knights of old and they hoped to regain some of that noble, courtly behaviour and impress it upon the people both at home and in the wider empire. The best example of this is Alfred Tennyson's Idylls of the King, which blended the stories of King Arthur, particularly those by Thomas Malory, with contemporary concerns and ideas. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood also drew on myth and folklore for their art, with Dante Gabriel Rossetti contemporaneously regarded as the chief poet amongst them, although his sister Christina is now held by scholars to be a stronger poet.

Drama

In drama, farces, musical burlesques, extravaganzas and comic operas competed with Shakespeare productions and serious drama by the likes of James Planché and Thomas William Robertson. In 1855, the German Reed Entertainments began a process of elevating the level of (formerly risqué) musical theatre in Britain that culminated in the famous series of comic operas by Gilbert and Sullivan and were followed by the 1890s with the first Edwardian musical comedies. The first play to achieve 500 consecutive performances was the London comedy Our Boys by H. J. Byron, opening in 1875. Its astonishing new record of 1,362 performances was bested in 1892 by Charley's Aunt by Brandon Thomas.[2] After W. S. Gilbert, Oscar Wilde became the leading poet and dramatist of the late Victorian period.[3] Wilde's plays, in particular, stand apart from the many now forgotten plays of Victorian times and have a closer relationship to those of the Edwardian dramatists such as George Bernard Shaw, whose career began in the 1890s. Wilde's 1895 comic masterpiece, The Importance of Being Earnest, was the greatest of the plays in which he held an ironic mirror to the aristocracy while displaying virtuosic mastery of wit and paradoxical wisdom. It has remained extremely popular.

Children's literature

The Victorians are credited with 'inventing childhood', partly via their efforts to stop child labour and the introduction of compulsory education. As children began to be able to read, literature for young people became a growth industry, with not only established writers producing works for children (such as Dickens' A Child's History of England) but also a new group of dedicated children's authors. Writers like Lewis Carroll, R. M. Ballantyne and Anna Sewell wrote mainly for children, although they had an adult following. Other authors such as Anthony Hope and Robert Louis Stevenson wrote mainly for adults, but their adventure novels are now generally classified as for children. Other genres include nonsense verse, poetry which required a childlike interest (e.g. Lewis Carroll). School stories flourished: Thomas Hughes' Tom Brown's Schooldays and Kipling's Stalky & Co. are classics.

Rarely were these publications designed to capture a child’s pleasure; however, with the increase in use of illustrations, children began to enjoy literature, and were able to learn morals in a more entertaining way.[4] With the newfound acceptance of reading for pleasure, fairy tales and folk tales became popular. Compiling folk tales by many authors with different topics made it possible for children to read literature by and about lots of different things that interested them. There were different types of books and magazines written for boys and girls. Girls' stories tended to be domestic and to focus on family life, whereas boys' stories were more about adventures.[5][6]

Science, philosophy and discovery

The Victorian era was an important time for the development of science and the Victorians had a mission to describe and classify the entire natural world. Much of this writing does not rise to the level of being regarded as literature but one book in particular, Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, remains famous. The theory of evolution contained within the work shook many of the ideas the Victorians had about themselves and their place in the world. Although it took a long time to be widely accepted, it would dramatically change subsequent thought and literature. Much of the work of popularizing Darwin's theories was done by his younger contemporary Thomas Henry Huxley, who wrote widely on the subject.

A number of other non-fiction works of the era made their mark on the literature of the period. The philosophical writings of John Stuart Mill covered logic, economics, liberty and utilitarianism. The large and influential histories of Thomas Carlyle: The French Revolution, A History and On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History permeated political thought at the time. The writings of Thomas Babington Macaulay on English history helped codify the Whig narrative that dominated the historiography for many years. John Ruskin wrote a number of highly influential works on art and the history of art and championed such contemporary figures as J. M. W. Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites. The religious writer John Henry Newman's Oxford Movement aroused intense debate within the Church of England, exacerbated by Newman's own conversion to Catholicism, which he wrote about in his autobiography Apologia Pro Vita Sua.

A number of monumental reference works were published in this era, most notably the Oxford English Dictionary which would eventually become the most important historical dictionary of the English language. Also published during the later Victorian era were the Dictionary of National Biography and the ninth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Nature writing

In the USA, Henry David Thoreau's works and Susan Fenimore Cooper's Rural Hours (1850) were canonical influences on Victorian nature writing. In the UK, Philip Gosse and Sarah Bowdich Lee were two of the most popular nature writers in the early part of the Victorian era.[7] The Illustrated London News, founded in 1842, was the world's first illustrated weekly newspaper and often published articles and illustrations dealing with nature; in the second half of the 19th century, books, articles, and illustrations on nature became widespread and popular among an increasingly urbanized reading public.

Supernatural and fantastic literature

The old Gothic tales that came out of the late 19th century are the first examples of the genre of fantastic fiction. These tales often centred on larger-than-life characters such as Sherlock Holmes, famous detective of the times, Sexton Blake, Phileas Fogg, and other fictional characters of the era, such as Dracula, Edward Hyde, The Invisible Man, and many other fictional characters who often had exotic enemies to foil. Spanning the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a particular type of story-writing known as gothic. Gothic literature combines romance and horror in attempt to thrill and terrify the reader. Possible features in a gothic novel are foreign monsters, ghosts, curses, hidden rooms and witchcraft. Gothic tales usually take place in locations such as castles, monasteries, and cemeteries, although the gothic monsters sometimes cross over into the real world, making appearances in cities such as London.

The influence of Victorian literature

Writers from the United States and the British colonies of Australia, New Zealand and Canada were influenced by the literature of Britain and are often classed as a part of Victorian literature, although they were gradually developing their own distinctive voices.[8] Victorian writers of Canadian literature include Grant Allen, Susanna Moodie and Catherine Parr Traill. Australian literature has the poets Adam Lindsay Gordon and Banjo Paterson, who wrote Waltzing Matilda, and New Zealand literature includes Thomas Bracken and Frederick Edward Maning. From the sphere of literature of the United States during this time are some of the country's greats including: Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., Henry James, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry David Thoreau, Mark Twain and Walt Whitman.

The problem with the classification of "Victorian literature" is the great difference between the early works of the period and the later works which had more in common with the writers of the Edwardian period and many writers straddle this divide. People such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, H. G. Wells, Bram Stoker, H. Rider Haggard, Jerome K. Jerome and Joseph Conrad all wrote some of their important works during Victoria's reign but the sensibility of their writing is frequently regarded as Edwardian.

Other Victorian writers

|

|

See also

Notes

- ↑ Introduction and Notes for The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Penguin Books. 1996. ISBN 978-0-14-043474-3.

- ↑ "Article on long-runs in the theatre before 1920". Stagebeauty.net. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ Stedman, Jane W. (1996). W. S. Gilbert, A Classic Victorian & His Theatre, pp. 26–29. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816174-3

- ↑ Evans, Denise; Onorato, Mary. "Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism". enotes. Gale Cengage. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ↑ Khale, Brewster. "Early Children's Literature". Children's Books in the Victorian Era. International Library of Children's Literature. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ↑ Susina, Jan. "Children's Literature". faqs.org. The Gale Group, Inc. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ↑ Dawson, Carl (1979). Victorian High Noon: English Literature in 1850. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U. Press.

- ↑ http://www.online-literature.com/periods/victorian.php

External links

- The Victorian Web

- Victorian Literature - Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians at the British Library

- Victorian Women Writers Project

- Victorian Studies Bibliography

- Victorian Links

- Victorian Short Fiction Project

- Mostly-Victorian.com – Victorian literature from magazines such as The Strand.

- – Victorian Writers and Poets

| Preceded by Romanticism |

Victorian literature 1837–1901 |

Succeeded by Modernism |