Baraminology

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Creationism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

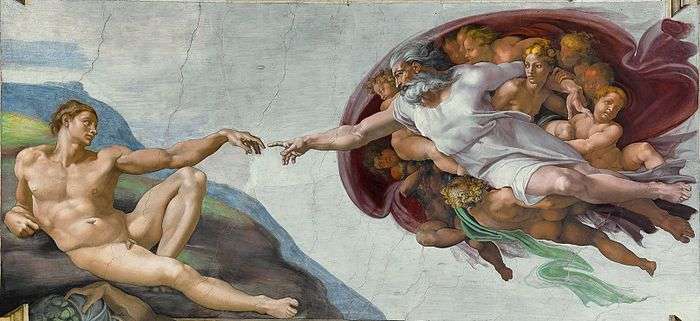

| ||||

| Types | ||||

| Biblical cosmology | ||||

| Creation science | ||||

| Creation–evolution controversy | ||||

| Religious views | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

Baraminology, a creationist system, classifies animals into groups called "created kinds" or "baramin" according to the account of creation in the book of Genesis and other parts of the Bible. It claims that kinds cannot interbreed and have no evolutionary relationship to one another.[1] The US National Academy of Science and numerous other scientific and scholarly organizations have criticized creation science for its pseudoscientific characteristics.[2][3][4]

Kurt P. Wise devised the word "baraminology" in 1990 on the basis of Frank Lewis Marsh's 1941 coinage of the term "baramin" from the Hebrew words bara (create) and min (kind). This combined word does not appear in Hebrew; instead, it is in reference to the use of the word kind in the Bible, particularly in Genesis (the creation narrative and the saving of animals in Noah's Ark), and in the division between clean and unclean animals in Leviticus and Deuteronomy.

Baraminology borrowed its key terminology, and much of its methodology, from the field of Discontinuity Systematics founded by Marsh in the 1940s.[5]

Distinction of created kinds

The question of determining the boundaries between baramin is a subject of much discussion and debate among creationists. A number of criteria have been presented.

Early efforts at demarcation

The concept of the "kind" or "baramin" originates from a fundamentalist interpretation of Genesis 1:12-24:

| “ | And God said, let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind … And God created great whales and every living creature that moveth, which the waters brought forth abundantly after their kind, and every winged fowl after his kind … And God said, let the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind, cattle and creeping thing, and beast of the earth after his kind, and it was so. | ” |

The traditional criterion for membership in a baramin was the ability to hybridize and create viable offspring. Frank Lewis Marsh coined the term baramin in his book Fundamental Biology (1941) and expanded on the concept in Evolution, Creation, and Science (c. 1944), in which he stated that hybridization was a sufficient condition for being members of the same baramin. However, he said that it was not a necessary condition, as observed speciation events among Drosophila fruitflies had been shown to cut off hybridization.

There is some uncertainty about what exactly the Bible means when it talks of "kinds." Creationist Brian Nelson claimed "While the Bible allows that new varieties may have arisen since the creative days, it denies that any new species have arisen." However, Russell Mixter, another creationary writer, said that "One should not insist that "kind" means species. The word "kind" as used in the Bible may apply to any animal which may be distinguished in any way from another, or it may be applied to a large group of species distinguishable from another group ... there is plenty of room for differences of opinion on what are the kinds of Genesis."[6]

In 1990 (and again in 1993), Walter ReMine proposed various criteria that he said were each sufficient by themselves to establish continuity between any two organisms. His criteria include (a) the ability to interbreed the two organisms, or (b) the ability to experimentally demonstrate comparable biological transformation in living organisms today, or (c) a clear-cut lineage between the two organisms. These criteria can be used in various combinations, among various organisms, to establish greater and greater continuity. He argued that the failure of all these methods is required in order to establish discontinuity.

History

The word "baramin" was coined in 1941 by Frank Marsh. Marsh never clearly defined the word and used it interchangeably in his writings with the word "kind", in reference to the phrase "after its kind" found repeatedly in Genesis.[7] Marsh's interpretation of Genesis was that each kind or baramin had been directly created by God and that only members of the same kind could reproduce, with their offspring also being members of the same kind.[7]

Marsh also originated "discontinuity systematics", the idea that there are boundaries between different animals that cannot be crossed with the consequence that there would be discontinuities in the history of life and limits to common ancestry.[5]

In 1990, Kurt Wise introduced baraminology as an adaptation of discontinuity systematics, particularly the concurrent work of Walter ReMine, that was more in keeping with young Earth creationism. Wise advocated using the Bible as a source of systematic data.[7] Baraminology and its associated concepts have been criticised by scientists and creationists for lacking formal structure. Consequently, in 2003 Wise and other creationists proposed a refined baramin concept in the hope of developing a broader creationary model of biology.[7] Alan Gishlick, reviewing the work of baraminologists in 2006, found it to be surprisingly rigorous and internally consistent, but concluded that the methods did not work.[5]

Terminology

ReMine's discontinuity systematics specified four groupings: holobaramins, monobaramins, apobaramins, and polybaramins. These are, respectively, all things of one kind; some things of the same kind; groups of kinds; and any mixed grouping of things.[8] These groups correspond to the concepts of holophyly, monophyly, paraphyly, and polyphyly used in cladistics.[5]

Criticism

Baraminology has been heavily criticized for its lack of rigorous tests and post-study rejection of data to make it better fit the desired findings.[9] Baraminology has not produced any peer-reviewed scientific research.

In contrast, universal common descent is a well-established and tested scientific theory.[10] However, both cladistics (the field devoted to classifying living things according to the ancestral relationships between them) and the scientific consensus on transitional fossils are rejected by baraminologists.[11]

Some techniques employed in Baraminology have been used to demonstrate evolution, thereby calling baraminological conclusions into question.[12][13][14]

See also

References

- ↑ Wood et al. 2003, pp. 1-14

- ↑ The National Academies 1999

- ↑ "Statements from Scientific and Scholarly Organizations.". National Center for Science Education. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ↑ Williams, J. D. (2007). "Creationist Teaching in School Science: A UK Perspective". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 1 (1): 87–88. doi:10.1007/s12052-007-0006-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Gishlick, Alan (2006). "Baraminology". Reports of the National Center for Science Education. 26 (4): 17–21.

- ↑ Payne 1958, pp. 17-20

- 1 2 3 4 Wood et al. 2003, pp. 1-14.

- ↑ Frair, Wayne (2000). "Baraminology—Classification of Created Organisms". Creation Research Society Quarterly Journal. 37 (2): 82–91. Archived from the original on 2003-06-18.

- ↑ "A Review of Friar, W. (2000): Baraminology - Classification of Created Organism". Archived from the original on 2007-04-22.

- ↑ Theobald, Douglas, 29+ Evidences for Macroevolution

- ↑ About the BSG: Taxonomic Concepts and Methods Archived April 15, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.. Phrases to note are: "The mere assumption that the transformation had to occur because cladistic analysis places it at a hypothetical ancestral node does not constitute empirical evidence." and "A good example is Archaeopteryx, which likely represents its own unique baramin, distinct from both dinosaurs and modern birds."

- ↑ Phil Senter (2010). "Using creation science to demonstrate evolution: application of a creationist method for visualizing gaps in the fossil record to a phylogenetic study of coelurosaurian dinosaurs". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 23 (8): 1732–1743. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02039.x. PMID 20561133.

- ↑ Phil Senter (2010). "Using creation science to demonstrate evolution 2: morphological continuity within Dinosauria". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 24 (10): 2197–2216. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02349.x. PMID 21726330.

- ↑ Todd Charles Wood (2010). "Using creation science to demonstrate evolution? Senter's strategy revisited". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 24 (4): 914–918. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02208.x. PMID 21401768.

- The National Academies (1999). "Science and Creationism: A View from the National Academy of Sciences, Second Edition". National Academy Press. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

creation science is in fact not science and should not be presented as such in science classes.

- Payne, J. Barton (1958). "The Concept of "Kinds" In Scripture". Journal of the American Science Affiliation. 10 (December 1958): 17–20. Retrieved 2007-11-26. [Note this version appears to have been OCR-scanned without proofreading]

- Wood; Wise; Sanders; Doran (2003). "A Refined Baramin Concept". Occasional Papers of the Baraminology Study Group. pp. 1–14.

External links

- A Review of Friar, W. (2000): Baraminology - Classification of Created Organisms. (Thomas, August 2006)

- Friar, Wayne (Sep 2000), "Baraminology–Classification of Created Organisms", Creation Research Society Quarterly Journal, 37 (2): 82–91, retrieved 2007-07-18

- About the BSG: Taxonomic Concepts and Methods

- Ligers and wholphins? What next? Crazy mixed-up animals … what do they tell us? They seem to defy man-made classification systems — but what about the created ‘kinds’ in Genesis?, Don Batten, Creation ex nihilo, 22(3):28–33, June 2000

- Gishlick, Alan, Baraminology: Systematic Discontinuity in Discontinuity Systematics, National Center for Science Education, retrieved 2007-07-18