Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation

The Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation is a geological unit which forms part of the Wealden Group and the uppermost and youngest part of the unofficial Hastings Beds. These geological units make up the core of the geology of the Weald in the English counties of West Sussex, East Sussex and Kent.

The other component formations of the Hastings Beds are the underlying Wadhurst Clay Formation and the Ashdown Formation. The Hastings Beds in turn form part of the Wealden Group which underlies much of southeast England. The sediments of the Weald, including the Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation, were deposited during the Early Cretaceous Period, which lasted for approximately 40 million years from 140 to 100 million years ago. The Tunbridge Wells Sands are of Late Valanginian age.[1] The Formation takes its name from the spa town of Tunbridge Wells in Kent.

Lithology

The Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation comprises complex cyclic sequences of siltstones with sandstones and clays, typically fining upwards, and is lithologically similar to the older Ashdown Formation.[2] It has a total thickness typically in the region of about 75 m.[1] However, near Haywards Heath borehole data has proven the formation to be up to 150m thick.[3]

In the western parts of the High Weald the Tunbridge Wells Sands can be divided into three separate members; the Lower Tunbridge Wells Sand Member, the Grinstead Clay Member, and the Upper Tunbridge Wells Sand Member.[3]

Lower Tunbridge Wells Sand Member

The Lower Tunbridge Wells Sand shows the best cyclic fining up sequences in the formation. The division comprises mainly interbedded siltstones and silty sandstones and occurs up to 27m thick.[4]

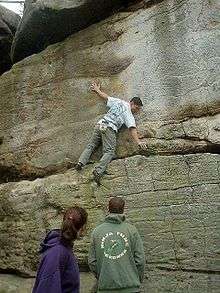

A massive thick cross bedded fine to medium grained quartz sandstone separates the Tunbridge Wells Sands from the overlying Grinstead Clay. This horizon is known as the Ardingly Sandstone and occurs in thicknesses of up to 12m. It is particularly well exposed throughout the region between East Grinstead, West Sussex, and Tunbridge Wells, Kent, at localities such as; Stone Farm south of East Grinstead; Chiddinglye Rocks near West Hoathly; Toad Rock, Bull’s Hollow and Happy Valley west of Tunbridge Wells; and Harrisons Rocks, Bowles Rocks and High Rocks near Crowborough. At all of these places the Ardingly Sandstone forms a weathering resistant layer, relative to the rest of the formation, which has become very popular with rock climbers and is known locally as Southern Sandstone. These are the closest rock climbing crags to London and as a result are the most heavily used in the country.[5]

Grinstead Clay Member

The Grinstead Clay comprises mudstones and silty mudstones with siltstone, ironstone and shelly limestone. This member is lithologically similar to the older Wadhurst Clay and also has weathered red mottled clays at its top. The formation is up to 20m thick but is only present around the border of East Sussex and West Sussex. It can be further subdivided into the Lower Grinstead Clay and Upper Grinstead Clay.[3] These divisions are separated by a lenticular calcareous sandstone known as the Cuckfield Stone. This is probably best known as the strata in which Gideon Mantell discovered Iguanodon in the early 19th century.[2]

Upper Tunbridge Wells Sand Member

The Upper Tunbridge Wells Sand is similar to the Lower Tunbridge Wells Sand. It comprises soft red and grey mottled silts and clays in its lower part, and alternating silts and silty clays with thin beds of sandstones.[2]

The base of the Tunbridge Wells Sand is marked by a distinct change from the predominantly argillaceous sediments of the Wadhurst Clay to siltstones and silty sands. This boundary is often indicated on maps by spring lines and seepages, where groundwater percolating through the permeable Tunbridge Wells Sand is forced to surface at the junction with the Wadhurst Clay.

The top of the Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation is well defined in the southwest of East Sussex but is gradational elsewhere. In the area north of Brighton and west of Lewes the boundary is marked by a massive sandstone, though this is not seen anywhere else.[4]

Engineering Geology

Landslips often occur at or close to the lower boundary of the Tunbridge Wells Sands, between it and the underlying Wadhurst Clay Formation. This is partly caused by the steep sided hill, valley and ravine topography of the High Weald and partly by the lithological variation between the formations and the presence of spring lines and seepages.[2]

When percolating groundwater in the permeable sandstones of the Tunbridge Wells Sands comes into contact with the upper impermeable clay beds of the Wadhurst Clay, it is forced to find alternative migration pathways to the surface. This results in the saturation and weakening of the upper portion of the Wadhurst Clay, increasing the chances of failure.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 Hopson, P.M., Wilkinson, I.P. and Woods, M.A. (2010) A stratigraphical framework for the Lower Cretaceous of England. Research Report RR/08/03. British Geological Survey, Keyworth.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Codd, J.W. (2007) Analysis of the distribution and characteristics of landslips in the Weald of East Sussex. MSc dissertation, University of Brighton.

- 1 2 3 Young, B. & Lake, R.D. (1988) Geology of the country around Brighton and Worthing: Memoir for 1:50,000 geological sheets 318 and 333. British Geological Survey, London.

- 1 2 Lake, R.D. & Shepard-Thorn, E.R. (1987) Geology of the country around Hastings and Dungeness: Memoir for 1:50,000 geological sheets 320 and 321. British Geological Survey, London.

- ↑ Messenger, Alex (9 July 2011). "Southern Sandstone: guidelines". The British Mountaineering Council.