London Underground

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Greater London, Buckinghamshire, Essex, Hertfordshire |

| Transit type | Rapid transit |

| Number of lines | 11[1] |

| Number of stations | 270 served[1] (260 owned) |

| Daily ridership | 4.8 million [2] |

| Annual ridership | 1.34 billion (2015/16)[3] |

| Website | London Underground |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | 10 January 1863 |

| Operator(s) | London Underground Limited |

| Reporting marks | LT (National Rail)[4] |

| Technical | |

| System length | 402 km (250 mi)[1] |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | 630 V DC fourth rail |

| Average speed | 33 km/h (21 mph)[5] |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| The Tube |

|---|

|

|

|

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground, or by its nickname the Tube) is a public rapid transit system serving Greater London and some adjacent parts of the counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in the United Kingdom.

The world's first underground railway, the Metropolitan Railway, which opened in 1863, is now part of the Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan lines; the first line to operate underground electric traction trains, the City & South London Railway in 1890, is now part of the Northern line.[6] The network has expanded to 11 lines, and in 2015–16 carried 1.34 billion passengers,[3] making it the world's 11th busiest metro system. The 11 lines collectively handle approximately 4.8 million passengers a day.[2]

The system's first tunnels were built just below the surface, using the cut-and-cover method; later, smaller, roughly circular tunnels – which gave rise to its nickname, the Tube – were dug through at a deeper level.[7] The system has 270 stations and 250 miles (400 km) of track.[8] Despite its name, only 45% of the system is actually underground in tunnels, with much of the network in the outer environs of London being on the surface.[8] In addition, the Underground does not cover most southern parts of Greater London, with less than 10% of the stations located south of the River Thames.[8]

The early tube lines, originally owned by several private companies, were brought together under the "UndergrounD" brand in the early 20th century and eventually merged along with the sub-surface lines and bus services in 1933 to form London Transport under the control of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB). The current operator, London Underground Limited (LUL), is a wholly owned subsidiary of Transport for London (TfL), the statutory corporation responsible for the transport network in Greater London.[7] As of 2015, 92% of operational expenditure is covered by passenger fares.[9] The Travelcard ticket was introduced in 1983 and Oyster, a contactless ticketing system, in 2003. Contactless card payments were introduced in 2014.[10]

The LPTB was a prominent patron of art and design, commissioning many new station buildings, posters and public artworks in a modernist style. The schematic Tube map, designed by Harry Beck in 1931, was voted a national design icon in 2006 and now includes other TfL transport systems such as the Docklands Light Railway, London Overground and TfL Rail. Other famous London Underground branding includes the roundel and Johnston typeface, created by Edward Johnston in 1916.

History

Early years

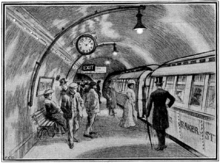

The idea of an underground railway linking the City of London with some of the railway termini in its urban centre was proposed in the 1830s,[12] and the Metropolitan Railway was granted permission to build such a line in 1854.[13] To prepare construction, a short test tunnel was built in 1855 in Kibblesworth, a small town with geological properties similar to London. This test tunnel was used for two years in the development of the first underground train, and was later, in 1861, filled up.[14] The world's first underground railway, it opened in January 1863 between Paddington and Farringdon using gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives.[15] It was hailed as a success, carrying 38,000 passengers on the opening day, and borrowing trains from other railways to supplement the service.[16] The Metropolitan District Railway (commonly known as the District Railway) opened in December 1868 from South Kensington to Westminster as part of a plan for an underground "inner circle" connecting London's main-line termini.[17] The Metropolitan and District railways completed the Circle line in 1884,[18] built using the cut and cover method.[19] Both railways expanded, the District building five branches to the west reaching Ealing, Hounslow,[20] Uxbridge,[21] Richmond and Wimbledon[20] and the Metropolitan eventually extended as far as Verney Junction in Buckinghamshire, more than 50 miles (80 km) from Baker Street and the centre of London.[22]

For the first deep-level tube line, the City and South London Railway, two 10 feet 2 inches (3.10 m) diameter circular tunnels were dug between King William Street (close to today's Monument station) and Stockwell, under the roads to avoid the need for agreement with owners of property on the surface. This opened in 1890 with electric locomotives that hauled carriages with small opaque windows, nicknamed padded cells.[23] The Waterloo and City Railway opened in 1898,[24] followed by the Central London Railway in 1900, known as the "twopenny tube".[25] These two ran electric trains in circular tunnels having diameters between 11 feet 8 inches (3.56 m) and 12 feet 2.5 inches (3.721 m),[26] whereas the Great Northern and City Railway, which opened in 1904, was built to take main line trains from Finsbury Park to a Moorgate terminus in the City and had 16-foot (4.9 m) diameter tunnels.[27]

In the early 20th century, the District and Metropolitan railways needed to electrify and a joint committee recommended an AC system, the two companies co-operating because of the shared ownership of the inner circle. The District, needing to raise the finance necessary, found an investor in the American Charles Yerkes who favoured a DC system similar to that in use on the City & South London and Central London railways. The Metropolitan Railway protested about the change of plan, but after arbitration by the Board of Trade, the DC system was adopted.[28]

The Underground Electric Railways Company years

Yerkes soon had control of the District Railway and established the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) in 1902 to finance and operate three tube lines, the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (Bakerloo), the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (Hampstead) and the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway, (Piccadilly), which all opened between 1906 and 1907.[29][30] When the "Bakerloo" was so named in July 1906, The Railway Magazine called it an undignified "gutter title".[30] By 1907 the District and Metropolitan Railways had electrified the underground sections of their lines.[31]

In January 1913, the UERL acquired the Central London Railway and the City & South London Railway, as well as many of London's bus and tram operators.[32] Only the Metropolitan Railway, along with its subsidiaries the Great Northern & City Railway and the East London Railway, and the Waterloo & City Railway, by then owned by the main line London and South Western Railway, remained outside of the Underground Group's control.[33]

A joint marketing agreement between most of the companies in the early years of the 20th century included maps, joint publicity, through ticketing and UNDERGROUND signs outside stations in Central London.[34] The Bakerloo line was extended north to Queen's Park to join a new electric line from Euston to Watford, but World War I delayed construction and trains reached Watford Junction in 1917. During air raids in 1915 people used the tube stations as shelters.[35] An extension of the Central line west to Ealing was also delayed by the war and completed in 1920.[36] After the war government-backed financial guarantees were used to expand the network and the tunnels of the City and South London and Hampstead railways were linked at Euston and Kennington,[37] although the combined service was not named the Northern line until later.[38] The Metropolitan promoted housing estates near the railway with the "Metro-land" brand and nine housing estates were built near stations on the line. Electrification was extended north from Harrow to Rickmansworth, and branches opened from Rickmansworth to Watford in 1925 and from Wembley Park to Stanmore in 1932.[39][40] The Piccadilly line was extended north to Cockfosters and took over District line branches to Harrow (later Uxbridge) and Hounslow.[41]

The London Passenger Transport Board years

In 1933, most of London's underground railways, tramway and bus services were merged to form the London Passenger Transport Board, which used the London Transport brand.[42] The Waterloo & City Railway, which was by then in the ownership of the main line Southern Railway, remained with its existing owners.[43] In the same year that the London Passenger Transport Board was formed, Harry Beck's diagrammatic tube map appeared for the first time.[44]

In the following years, the outlying lines of the former Metropolitan Railway closed, the Brill Tramway in 1935, and the line from Quainton Road to Verney Junction in 1936.[45] The 1935–40 New Works Programme included the extension of the Central and Northern lines and the Bakerloo line to take over the Metropolitan's Stanmore branch.[46] World War II suspended these plans after the Bakerloo line had reached Stanmore and the Northern line High Barnet and Mill Hill East in 1941.[47] Following bombing in 1940 passenger services over the West London Line were suspended, leaving Olympia exhibition centre without a railway service until a District line shuttle from Earl's Court began after the war.[48] After work restarted on the Central line extensions in east and west London, these were complete in 1949.[49]

During the war many tube stations were used as air-raid shelters.[50] On 3 March 1943, a test of the air-raid warning sirens, together with the firing of a new type of anti-aircraft rocket, resulted in a crush of people attempting to take shelter in Bethnal Green tube station. A total of 173 people, including 62 children, died, making this both the worst civilian disaster of World War II, and the largest loss of life in a single incident on the London Underground network.[51]

The London Transport Executive / Board years

On 1 January 1948, under the provisions of the Transport Act 1947, the London Passenger Transport Board was nationalised and renamed the London Transport Executive, becoming a subsidiary organisation of the British Transport Commission, which was formed on the same day.[52][53][54] Under the same act, the country's main line railways were also nationalised, and their reconstruction was given priority over the maintenance of the Underground and most of the unfinished plans of the pre-war New Works Programme were shelved or postponed.[55]

However, the District line needed new trains and an unpainted aluminium train entered service in 1953, this becoming the standard for new trains.[56] In the early 1960s the Metropolitan line was electrified as far as Amersham, British Rail providing services for the former Metropolitan line stations between Amersham and Aylesbury.[57] In 1962, the British Transport Commission was abolished, and the London Transport Executive was renamed the London Transport Board, reporting directly to the Minister of Transport.[53][58] Also during the 1960s, the Victoria line was dug under central London and, unlike the earlier tubes, the tunnels did not follow the roads above. The line opened in 1968–71 with the trains being driven automatically and magnetically encoded tickets collected by automatic gates gave access to the platforms.[59]

The Greater London Council years

On 1 January 1970 responsibility for public transport within Greater London passed from central government to local government, in the form of the Greater London Council (GLC), and the London Transport Board was abolished. The London Transport brand continued to be used by the GLC.[60]

On Friday 28 February 1975, a southbound train on the Northern City Line failed to stop at its Moorgate terminus and ploughed into the wall at the end of the tunnel. In the resulting tube crash, 43 people died and a further 74 were injured, this being the greatest loss of life during peacetime on the London Underground.[61] In 1976 the Northern City Line was taken over by British Rail and linked up with the main line railway at Finsbury Park, a transfer that had already been planned prior to the accident.[62]

In 1979 another new tube, the Jubilee line, named in honour of Queen Elizabeth's Silver Jubilee, took over the Stanmore branch from the Bakerloo line, linking it to a newly constructed tube between Baker Street and Charing Cross stations.[63] Under the control of the Greater London Council, London Transport introduced a system of fare zones for buses and underground trains that cut the average fare in 1981. Fares increased following a legal challenge but the fare zones were retained, and in the mid-1980s the Travelcard and the Capitalcard were introduced.[64]

The London Regional Transport years

In 1984 control of London Buses and the London Underground passed back to central government with the creation of London Regional Transport (LRT), which reported directly to the Secretary of State for Transport, whilst still retaining the London Transport brand.[65] One person operation had been planned in 1968, but conflict with the trade unions delayed introduction until the 1980s.[66]

On 18 November 1987, fire broke out in an escalator at King's Cross St. Pancras tube station. The resulting fire cost the lives of 31 people and injured a further 100. London Underground were strongly criticised in the aftermath for their attitude to fires underground, and publication of the report into the fire led to the resignation of senior management of both London Underground and London Regional Transport.[67] To comply with new safety regulations issued as a result of the fire, and to combat graffiti, a train refurbishment project was launched in July 1991.[68][69]

In April 1994, the Waterloo & City Railway, by then owned by British Rail and known as the Waterloo & City line, was transferred to the London Underground.[43] In 1999, the Jubilee line was extended from Green Park station through Docklands to Stratford station, resulting in the closure of the short section of tunnel between Green Park and Charing Cross stations, and including the first stations on the London Underground to have platform edge doors.[70]

The Transport for London years

Transport for London (TfL) was created in 2000 as the integrated body responsible for London's transport system. TfL is part of the Greater London Authority and is constituted as a statutory corporation regulated under local government finance rules.[71] The TfL Board is appointed by the Mayor of London, who also sets the structure and level of public transport fares in London. However the day-to-day running of the corporation is left to the Commissioner of Transport for London.[72]

TfL eventually replaced London Regional Transport, and discontinued the use of the London Transport brand in favour of its own brand. The transfer of responsibility was staged, with transfer of control of the London Underground delayed until July 2003, when London Underground Limited became an indirect subsidiary of TfL.[71][73] Between 2000 and 2003, London Underground was reorganised in a Public-Private Partnership where private infrastructure companies (infracos) upgraded and maintained the railway. This was undertaken before control passed to TfL, who were opposed to the arrangement.[74] One infraco went into administration in 2007 and TfL took over the responsibilities, TfL taking over the other in 2010.[75]

Electronic ticketing in the form of the contactless Oyster card was introduced in 2003.[76] London Underground services on the East London line ceased in 2007 so that it could be extended and converted to London Overground operation,[77][78] and in December 2009 the Circle line changed from serving a closed loop around the centre of London to a spiral also serving Hammersmith.[79] From September 2014, passengers have been able to use contactless cards on the Tube,[80] the use of which has grown very quickly and now over a million contactless transactions are made on the Underground every day.[81]

Infrastructure

Railway

The Underground serves 270 stations.[1][82] Fourteen Underground stations are outside Greater London, of which five (Amersham, Chalfont & Latimer, Chesham, and Chorleywood on the Metropolitan line, and Epping on the Central line), are beyond the M25 London Orbital motorway. Of the 32 London boroughs, six (Bexley, Bromley, Croydon, Kingston, Lewisham and Sutton) are not served by the Underground network, while Hackney has Old Street and Manor House only just inside its boundaries. Lewisham used to be served by the East London Line (stations at New Cross and New Cross Gate). The line and the stations were transferred to the London Overground network in 2010.[83]

London Underground's eleven lines total 402 kilometres (250 mi) in length,[1] making it the third longest metro system in the world. These are made up of the sub-surface network and the deep-tube lines.[1] The Circle, District, Hammersmith & City, and Metropolitan lines form the sub-surface network, with railway tunnels just below the surface and of a similar size to those on British main lines. The Hammersmith & City and Circle lines share stations and most of their track with each other, as well as with the Metropolitan and District lines. The Bakerloo, Central, Jubilee, Northern, Piccadilly, Victoria and Waterloo & City lines are deep-level tubes, with smaller trains that run in two circular tunnels (tubes) with a diameter about 11 feet 8 inches (3.56 m). These lines have the exclusive use of a pair of tracks, except for the Piccadilly line, which shares track with the District line between Acton Town and Hanger Lane Junction and with the Metropolitan line between Rayners Lane and Uxbridge; and the Bakerloo line, which shares track with London Overground services north of Queen's Park.[84]

Fifty-five per cent of the system runs on the surface. There are 20 miles (32 km) of cut-and-cover tunnel and 93 miles (150 km) of tube tunnel.[1] Many of the central London underground stations on deep-level tube lines are higher than the running lines to assist deceleration when arriving and acceleration when departing.[85] Trains generally run on the left-hand track. However, in some places, the tunnels are above each other (for example, the Central line east of St Paul's station), or the running tunnels are on the right (for example on the Victoria line between Warren Street and King's Cross St. Pancras, to allow cross-platform interchange with the Northern line at Euston).[84][86]

The lines are electrified with a four-rail DC system: a conductor rail between the rails is energised at −210 V and a rail outside the running rails at +420 V, giving a potential difference of 630 V. On the sections of line shared with mainline trains, such as the District line from East Putney to Wimbledon and Gunnersbury to Richmond, and the Bakerloo line north of Queen's Park, the centre rail is bonded to the running rails.[87]

Lines

The London Underground was used by 1.34 billion passengers in 2015/2016.[3]

| Name | Map colour[88] | Opening Date | Type | Length | No. Stations |

Current Stock | Trips per annum |

Avg. trips per mile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (×1000) 2011/12 figures[89] | ||||||||||

| Bakerloo line | Brown | 1906 | Deep Tube |

23.2 km 14.5 mi |

25 | 1972 Stock | 111,136 | 7,665 | ||

| Central line | Red | 1900[lower-alpha 1] | Deep Tube |

74 km 46 mi |

49 | 1992 Stock | 260,916 | 5,672 | ||

| Circle line | Yellow | 1871[lower-alpha 2] | Sub surface |

27.2 km 17 mi |

36 | S7 Stock[92] | 114,609[lower-alpha 3] | 4,716 | ||

| District line | Green | 1868 | Sub surface |

64 km 40 mi |

60 | D78 Stock S7 Stock[92] |

208,317 | 5,208 | ||

| Hammersmith & City line | Pink | 1864[lower-alpha 4] | Sub surface |

25.5 km 15.9 mi |

29 | S7 Stock[92] | 114,609[lower-alpha 3] | 4,716 | ||

| Jubilee line | Grey | 1979 | Deep Tube |

36.2 km 22.5 mi |

27 | 1996 Stock | 213,554 | 9,491 | ||

| Metropolitan line | Purple | 1863 | Sub surface |

66.7 km 41.5 mi |

34 | S8 Stock | 66,779 | 1,609 | ||

| Northern line | Black | 1890[lower-alpha 5] | Deep Tube |

58 km 36 mi |

50 | 1995 Stock | 252,310 | 7,009 | ||

| Piccadilly line | Dark Blue | 1906 | Deep Tube |

71 km 44.3 mi |

53 | 1973 Stock | 210,169 | 4,744 | ||

| Victoria line | Light Blue | 1968 | Deep Tube |

21 km 13.3 mi |

16 | 2009 Stock | 199,988 | 15,093 | ||

| Waterloo & City line | Turquoise | 1898[lower-alpha 6] | Deep Tube |

2.5 km 1.5 mi |

2 | 1992 Stock | 15,892 | 10,595 | ||

| ||||||||||

Services using former and current main lines

The Underground uses a number of railways and alignments that were built by main-line railway companies.

- Bakerloo line: Between Queen's Park and Harrow & Wealdstone this runs over the Watford DC Line alongside the London & North Western Railway (LNWR) main line that opened in 1837. The route was laid out by the LNWR in 1912–15 and is part of the Network Rail system.

- Central line: The railway from just south of Leyton to just south of Loughton was built by Eastern Counties Railway in 1856 on the same alignment in use today.[94] The Underground also uses the line built in 1865 by the Great Eastern Railway (GER) between Loughton to Ongar via Epping. The connection to the main line south of Leyton was closed in 1970 and removed in 1972. The line from Epping to Ongar was closed in 1994; most of the line is in use today by the heritage Epping Ongar Railway.[94] The line between Newbury Park and Woodford junction (west of Roding Valley) via Hainault was built by the GER in 1903, the connections to the main line south of Newbury Park closing in 1947 (in the Ilford direction) and 1956 (in the Seven Kings direction).[94]

- Central line: The line from just north of White City to Ealing Broadway was built in 1917 by the Great Western Railway (GWR) and passenger service introduced by the Underground in 1920. North Acton to West Ruislip was built by GWR on behalf of the Underground in 1947–8 alongside the pre-existing tracks from Old Oak Common junction towards High Wycombe and beyond, which date from 1904.[94] As of May 2013, the original Old Oak Common junction to South Ruislip route has one main-line train a day to/from Paddington.[95]

- District line: South of Kensington Olympia short sections of the 1862 West London Railway (WLR) and its 1863 West London Extension Railway (WLER) were used when District extended from Earl's Court in 1872. The District had its own bay platform at Olympia built in 1958 along with track on the bed of the 1862/3 WLR/WLER northbound. The southbound WLR/WLER became the new northbound main line at that time, and a new southbound main-line track was built through the site of former goods yard. The 1872 junction closed in 1958, and a further connection to the WLR just south of Olympia closed in 1992. The branch is now segregated.[94]

- District line: The line between Campbell Road junction (now closed), near Bromley-by-Bow, and Barking was built by the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway (LTSR) in 1858. The slow tracks were built 1903–05, when District services were extended from Bow Road (though there were no District services east of East Ham from 1905 to 1932). The slow tracks were shared with LTSR stopping and goods trains until segregated by 1962, when main-line trains stopped serving intermediate stations.[94]

- District line: The railway from Barking to Upminster was built by LTSR in 1885 and the District extended over the route in 1902. District withdrew between 1905 and 1932, when the route was quadrupled. Main-line trains ceased serving intermediate stations in 1962, and the District line today only uses the 1932 slow tracks.[94]

- District line: The westbound track between east of Ravenscourt Park and Turnham Green and Turnham Green to Gunnersbury follows the alignment of a railway built by the London & South Western Railway (LSWR) in 1869. The eastbound track between Turnham Green and east of Ravenscourt Park follows the alignment built in 1911; this was closed 1916 but was re-used when the Piccadilly line was extended in 1932.[94]

- District line: The line between East Putney and Wimbledon was built by the LSWR in 1889. The last scheduled main-line service ran in 1941[94] but it still sees a few through Waterloo passenger services at the start and end of the daily timetable.[96] The route is also used for scheduled ECS movements to/from Wimbledon Park depot and for Waterloo services diverted during disruptions and track closures elsewhere.

- Hammersmith & City: Between Paddington and Westbourne Park tube station, the line runs alongside the main line. The Great Western main line opened in 1838, serving a temporary terminus the other side of Bishop's Road. When the current Paddington station opened in 1854, the line passed to the south of the old station.[94] On opening in 1864, the Hammersmith & City (then part of the Metropolitan line) ran via the main line to a junction at Westbourne Park, until 1867 when two tracks opened to the south of the main line, with a crossing near Westbourne Bridge, Paddington. The current two tracks to the north of the main line and the subway east of Westbourne Park opened in 1878.[97] The Hammersmith & City route is now completely segregated from the main line.

- Jubilee line: The rail route between Canning Town and Stratford was built by the GER in 1846, with passenger services starting in 1847. The original alignment was quadrupled "in stages between 1860 and 1892" for freight services before the extra (western) tracks were lifted as traffic declined during the 20th century, and were re-laid for Jubilee line services that started in 1999. The current Docklands Light Railway (ex-North London Line) uses the original eastern alignment and the Jubilee uses the western alignment.[94]

- Northern line: The line from East Finchley to Mill Hill East was opened in 1867, and from Finchley Central to High Barnet in 1872, both by the Great Northern Railway.[94]

- Piccadilly line: The westbound track between east of Ravenscourt Park and Turnham Green was built by LSWR in 1869, and originally used for eastbound main-line and District services. The eastbound track was built in 1911; it closed in 1916 but was re-used when the Piccadilly line was extended in 1932.[94]

Main line services that use LU tracks

Some tracks now in LU ownership remain in use by main line services.

- District line – East Putney to Wimbledon, used by South West Trains on through, ECS and diverted services[98]

- Metropolitan line – Harrow-on-the-Hill to Mantles Wood (west of Amersham), used by Chiltern Railways Marylebone to Aylesbury/Aylesbury Vale services

Trains

London Underground trains come in two sizes, larger sub-surface trains and smaller deep-tube trains.[99] Since the early 1960s all passenger trains have been electric multiple units with sliding doors[100] and a train last ran with a guard in 2000.[101] All lines use fixed length trains with between six and eight cars, except for the Waterloo & City line that uses four cars.[102] New trains are designed for maximum number of standing passengers and for speed of access to the cars and have regenerative braking and public address systems.[103] Since 1999 all new stock has had to comply with accessibility regulations that require such things as access and room for wheelchairs, and the size and location of door controls. All underground trains are required to comply with the The Rail Vehicle Accessibility (Non Interoperable Rail System) Regulations 2010 (RVAR 2010) by 2020.[104]

Stock on sub-surface lines is identified by a letter (such as S Stock, used on the Metropolitan line), while tube stock is identified by the year of intended introduction[105] (for example, 1996 Stock, used on the Jubilee line).

Depots

The Underground is served by the following depots:

- Bakerloo: London Road, Stonebridge Park

- Central: Hainault, Ruislip, White City

- Circle: Hammersmith, Neasden

- District: Ealing Common, Hammersmith, Upminster

- Hammersmith & City: Hammersmith, Neasden

- Jubilee: Neasden, Stratford Market

- Metropolitan: Neasden

- Northern: Edgware, Golders Green, High Barnet, Highgate, Morden

- Piccadilly: Cockfosters, Northfields

- Victoria: Northumberland Park

- Waterloo & City: Waterloo

- London Transport Museum: Acton Town

Ventilation and cooling

When the Bakerloo line opened in 1906 it was advertised with a maximum temperature of 60 °F (16 °C), but over time the tube tunnels have warmed up. In 1938 approval was given for a ventilation improvement programme, and a refrigeration unit was installed in a lift shaft at Tottenham Court Road.[106] Temperatures of 47 °C (117 °F) were reported in the 2006 European heat wave.[107] It was claimed in 2002 that, if animals were being transported, temperatures on the Tube would break European Commission animal welfare laws.[108] A 2000 study reported that air quality was seventy-three times worse than at street level, with a passenger breathing the same mass of particulates during a twenty-minute journey on the Northern line as when smoking a cigarette.[109][110] The main purpose of the London Underground's ventilation fans is to extract hot air from the tunnels,[106] and fans across the network are being refurbished, although complaints of noise from local residents preclude their use at full power at night.[111]

In June 2006 a groundwater cooling system was installed at Victoria station.[112] In 2012, air-cooling units were installed on platforms at Green Park station using cool deep groundwater and at Oxford Circus using chiller units at the top of an adjacent building.[113] New air-conditioned trains are being introduced on the sub-surface lines, but space is limited on tube trains for air-conditioning units and these would heat the tunnels even more. The Deep Tube Programme, investigating replacing the trains for the Bakerloo and Piccadilly lines, is looking for trains with better energy conservation and regenerative braking, on which it might be possible to install a form of air conditioning.[103][114]

In the original Tube design, trains passing through close fitting tunnels act as pistons to create air pressure gradients between stations. This pressure difference drives ventilation between platforms and the surface exits through the passenger foot network. This system depends on adequate cross sectional area of the airspace above the passengers’ heads in the foot tunnels and escalators, where laminar airflow is proportional to the fourth power of the radius, the Hagen–Poiseuille equation. It also depends on an absence of turbulence in the tunnel headspace. In many stations the ventilation system is now ineffective because of alterations that reduce tunnel diameters and increase turbulence. An example is Green Park tube station, where false ceiling panels attached to metal frames have been installed that reduce the above-head airspace diameter by more than half in many parts. This has the effect of reducing laminar airflow by some 94%, Hagen–Poiseuille equation.

Originally air turbulence was kept to a minimum by keeping all signage flat to the tunnel walls. Now the ventilation space above head height is crowded with ducting, conduits, cameras, speakers and equipment acting as a baffle plates with predictable reductions in flow.[115] Often electronic signs have their flat surface at right angles to the main air flow, causing choked flow. Temporary sign boards that stand at the top of escalators also maximise turbulence. The alterations to the ventilation system are important, not only to heat exchange, but also the quality of the air at platform level, particularly given its asbestos content.[116]

Lifts and escalators

Originally access to the deep-tube platforms was by a lift.[117] Each lift was staffed, and at some quiet stations in the 1920s the ticket office was moved into the lift, or it was arranged that the lift could be controlled from the ticket office.[118] The first escalator on the London Underground was installed in 1911 between the District and Piccadilly platforms at Earl's Court and from the following year new deep-level stations were provided with escalators instead of lifts.[119] The escalators had a diagonal shunt at the top landing.[119][120] In 1921 a recorded voice instructed passengers to stand on the right and signs followed in World War II.[121] Travellers were asked to stand on the right so that anyone wishing to overtake them would have a clear passage on the left side of the escalator.[122] The first 'comb' type escalator was installed in 1924 at Clapham Common.[119] In the 1920s and 1930s many lifts were replaced by escalators.[123] After the fatal 1987 King's Cross fire, all wooden escalators were replaced with metal ones and the mechanisms are regularly degreased to lower the potential for fires.[124] The only wooden escalator not to be replaced was at Greenford station, which remained until October 2015 when TfL replaced it with the first incline lift on the UK transport network.[125]

There are 426 escalators on the London Underground system and the longest, at 60 metres (200 ft), is at Angel. The shortest, at Stratford, gives a vertical rise of 4.1 metres (13 ft). There are 164 lifts,[1] and numbers have increased in recent years because of a programme to increase accessibility.[126]

Wi-Fi and mobile phone reception

In summer 2012 London Underground, in partnership with Virgin Media, tried out Wi-Fi hot spots in many stations, but not in the tunnels, that allowed passengers free internet access. The free trial proved successful and was extended to the end of 2012[127] whereupon it switched to a service freely available to subscribers to Virgin Media and others, or as a paid-for service.[128] Even without subscribing to paid-for Wi-Fi services, the free signals can be used by smartphones to alert a traveller that they have arrived at a specific station.[129] It is not currently possible to use mobile phones underground using native 2G, 3G or 4G networks, and a project to extend coverage before the 2012 Olympics was abandoned because of commercial and technical difficulties.[130] UK subscribers to the O2 or Three mobile networks can use the Tu Go[131] or InTouch[132] apps respectively to route their voice calls and texts messages via the Virgin Media Wifi network at 138 London Transport stations.[133] The EE network also has recently released a WiFi calling feature available on the iPhone.[134]

Proposed improvements and expansions

New lines

The Elizabeth line, under the project name Crossrail, is under construction and expected to open in stages until 2018, providing a new underground route across central London integrated with, but not part of the London Underground system.[135][136][137] A part of National Rail which will become part of Crossrail, and which has already been completed, is currently running under the name "TfL Rail". The new line will use Class 345 trains,[138] currently build and tested by Bombardier in Derby, UK, and serve 40 stations. Two options are being considered for the route of Crossrail 2 on a north-south alignment across London, with hopes that it could be open by 2033.[139]

Line extensions

Croxley Rail Link

The Croxley Rail Link involves re-routing the Metropolitan line's Watford branch from the current terminus at Watford over part of the disused Croxley Green branch line to Watford Junction with stations at Cassiobridge, Watford Vicarage Road and Watford High Street (which is currently only a part of London Overground). Funding was agreed in December 2011,[140] and the final approval for the extension was given on 24 July 2013.[141] Work is expected to start in 2016, with the aim of completion by 2020.[142]

Northern line extension to Battersea and Clapham Junction

It is planned that the Northern line be extended to Battersea with an intermediate station at Nine Elms. In December 2012, the Treasury confirmed that it will provide a guarantee that allows the Greater London Authority to borrow up to £1 billion from the Public Works Loan Board, at a preferential rate, to finance the construction of the line.[143] In April 2013, Transport for London applied for the legal powers of a Transport and Works Act Order to proceed with the extension. Preparation works started in Spring 2015. The main tunnelling is due to start in 2017. The stations could open in 2020.[144][145]

Provision will be made for a possible future extension to Clapham Junction by notifying the London Borough of Wandsworth of a reserved course under Battersea Park and subsequent streets.[146]

Bakerloo line extension to Lewisham or Hayes via Camberwell or Old Kent Road

In 1931 the extension of the Bakerloo line from Elephant & Castle to Camberwell was approved, with stations at Albany Road and an interchange at Denmark Hill. However, with post-war austerity, the plan was abandoned. In 2006 Ken Livingstone, the then Mayor of London, announced that within twenty years Camberwell would have a tube station.[147] Transport for London has indicated that extensions, possibly to Camberwell, could play a part in the future transport strategy for South London over the coming years.[148] However, no such planning of an extension has been revealed. There have also been many other proposals to extend the line to Streatham, Lewisham, and even beyond Lewisham, taking over the suburban Hayes line via Catford Bridge to relieve some capacity on the suburban rail network.

Bakerloo line extension to Watford Junction

In 2006, as part of the planning for the transfer of the North London Line to what became London Overground, TfL proposed re-extending the Bakerloo line to Watford Junction.[149][150]

Central line extension to Uxbridge

The London Borough of Hillingdon has proposed that the Central line be extended from West Ruislip to Uxbridge via Ickenham, claiming this would cut traffic on the A40 in the area.[151]

Infrastructure

- Bakerloo line – The 36 1972-stock trains on the Bakerloo line have already exceeded their original design life of 40 years. London Underground is therefore extending their operational life by making major repairs to many of the trains to maintain reliability. The Bakerloo line will be part of the New Tube for London Project. This will replace the existing fleet with new air-cooled articulated trains and a new signalling system to allow Automatic Train Operation. The line is predicted to run a maximum of 27 trains per hour, a 25% increase from the current 21-trains-per-hour peak service.[152][153]

- Central line – The Central line was the first line to be modernized in the 1990s, with 85 new 1992-stock trains and a new automatic signalling system installed to allow Automatic Train Operation. The line runs 34 trains per hour for half an hour in the morning peak but is unable to operate more frequently because of a lack of additional trains. The 85 existing 1992-stock trains are the most unreliable on the London Underground as they are equipped with the first generation of solid state direct current thyristor control traction equipment. The trains often break down, have to be withdrawn from service at short notice and at times are not available when required, leading to gaps in service at peak times. Although relatively modern and well within their design life, the trains need work in the medium term to ensure the continued reliability of the traction control equipment and maintain fleet serviceability until renewal, which is expected between 2028 and 2032. Major work is to be undertaken on the fleet to ensure their continued reliability with brakes, traction control systems, doors, automatic control systems being repaired or replaced among other components. The Central line will be part of the New Tube for London Project. This will replace the existing fleet with new air-cooled walkthrough trains and a new more up-to-date automatic signalling system. The line is predicted to run 36 trains per hour, a 25% increase compared to the present service of 34 trains for busiest 30 minutes in the morning and evening peaks and the 27–30 train per hour service for the rest of the peak.[152][154][155]

- Jubilee line – The signalling system on the Jubilee line has been replaced to increase capacity on the line by 20%—the line now runs 30 trains per hour at peak times, compared to the previous 24 trains per hour. Similarly to the Victoria line the service frequency is planned to increase to 36 trains per hour. To enable this ventilation, power supply and control and signalling systems will be adapted and modified to allow the increase in frequency. London Underground also plans to add up to an additional 18 trains to the current fleet of 63 trains of 1996 stock.[156][157]

- Northern line – The signalling system on the Northern line has also been replaced to increase capacity on the line by 20%, as the line now runs 24 trains per hour at peak times, compared to 20 previously. Capacity can be increased further if the operation of the Charing Cross and Bank branches are separated. To enable this up to 50 additional trains will be built in addition to the current 106 1995 stock. The five trains will be required for the proposed Northern line extension and 45 to increase frequencies on the rest of the line. This combined with the segregation of trains at Camden Town junction will allow 30–36 trains per hour compared to 24 trains per hour currently.[158][159]

- Piccadilly line – The eighty-six 1973 stock trains that operate on the Piccadilly line are some of the most reliable trains on the London Underground. The trains have a design life of around 40 years and after 37 years are in need of replacement. The Piccadilly line will be part of the New Tube for London Project. This will replace the existing fleet with new air-cooled walkthrough trains and a new signalling system to allow Automatic Train Operation. The line is predicted to run 30–36 trains per hour up to a 60% increase compared to the 24/25 train per hour service provided today. The Piccadilly will be the first line to be upgraded as part of the New Tube for London Project as passenger usage has increased over recent years and is expected to increase further. This line is important in this project because it does not provide service that is as frequent a service as other lines.[152]

- Subsurface lines (District, Metropolitan, Hammersmith & City and Circle) – New S Stock trains are being introduced on the sub-surface (District, Metropolitan, Hammersmith & City and Circle) lines being scheduled for completion in 2016. 191 trains have been introduced or are being built: 58 for the Metropolitan line and 133 for the Circle, District and Hammersmith & City lines. The track, electrical supply and signalling systems are also being upgraded in a programme to increase peak-hour capacity. The replacement of the signalling system and the introduction of Automatic Train Operation/Control is scheduled for 2019–22. A control room for the sub-surface network has been built in Hammersmith and an automatic train control (ATC) system is to replace signalling equipment installed from the 1920s such as the signal box at Edgware Road, still manually operated. Bombardier won the contract in June 2011 but was released by agreement in December 2013, and London Underground has now issued another signalling contract, with Thales.[160][161][162]

- Victoria line – The signalling system on the Victoria line has been replaced to increase capacity on the line by around 25%; the line now runs up to 34 trains per hour compared to 27—28 previously. The trains have been replaced with 47 new higher-capacity 2009-stock trains. The peak frequency is set to increase further to 36 trains per hour in 2016 after track works at Walthamstow Central: at present only 24 trains per hour can be run beyond Seven Sisters station because of the layout of the points at Walthamstow Central crossover, which transfers northbound trains to the southbound line for their return journey. Renewal of the crossover is essential to achieve 36 trains per hour. This will result in a 40% increase in capacity between Seven Sisters and Walthamstow Central.[163]

- Waterloo & City line – The line was upgraded with five new 1992-stock trains in the early 1990s, at the same time as the Central line was upgraded. The line operates under traditional signalling and does not use Automatic Train Operation. The line will be part of the New Tube for London Project. This will replace the existing fleet with new air-cooled walkthrough trains and a new signaling system to allow Automatic Train Operation. The line is predicted to run 30 trains per hour, up to a 50% increase compared to the current 21-trains-per-hour service. The line may also be one of the first to be upgraded, alongside the Piccadilly line, with new trains, systems and platform-edge doors to test the systems before the Central and Bakerloo lines are upgraded.[152]

New trains for deep-level lines

In Summer 2014 Transport for London issued a tender for up to 18 trains for the Jubilee line and up to 50 trains for the Northern line. These would be used to increase frequencies and cover the Battersea extension on the Northern line.

In early 2014 the Bakerloo, Piccadilly, Central and Waterloo & City line rolling-stock replacement project was renamed New Tube for London (NTfL) and moved from the feasibility stage to the design and specification stage. The study had showed that, with new generation trains and re-signalling:

- Piccadilly line capacity could be increased by 60% with 33 trains per hour (tph) at peak times by 2025.

- Central line capacity increased by 25% with 33 tph at peak times by 2030.

- Waterloo & City line capacity increased by 50% by 2032, after the track at Waterloo station is remodelled.

- Bakerloo line capacity could be increased by 25% with 27 tph at peak times by 2033.

The project is estimated to cost £16.42 billon (£9.86 bn at 2013 prices). A notice was published on 28 February 2014 in the Official Journal of the European Union asking for expressions of interest in building the trains.[164][165] On 9 October 2014 TFL published a shortlist of those (Alstom, Siemens, Hitachi, CAF and Bombardier) who had expressed an interest in supplying 250 trains for between £1.0 billion and £2.5 billion, and on the same day opened an exhibition with a design by PriestmanGoode.[166][167] The fully automated trains may be able to run without drivers,[168] but the ASLEF and RMT trade unions that represent the drivers strongly oppose this, saying it would affect safety.[169] The Invitation to Tender for the trains was issued in January 2016;[170] the specifications for the Piccadilly line infrastructure are expected in 2016,[164][165] and the first train is due to run on the Piccadilly line in 2022.[167]

Travelling

Ticketing

The Underground uses Transport for London's zonal fare system to calculate fares. There are nine zones, zone 1 being the central zone, which includes the loop of the Circle line with a few stations to the south of River Thames. The only London Underground stations in Zones 7 to 9 are on the Metropolitan line beyond Moor Park, outside Greater London. Some stations are in two zones, and the cheapest fare applies.[171] Paper tickets, the contactless Oyster cards, contactless debit or credit cards [172] and Apple Pay smartphones and watches can be used for travel.[173] Single and return tickets are available in either format, but Travelcards (season tickets) for longer than a day are available only on Oyster cards.[174][175][176]

TfL introduced the Oyster card in 2003; this is a pre-payment smartcard with an embedded contactless RFID chip.[177] It can be loaded with Travelcards and used on the Underground, the Overground, buses, trams, the Docklands Light Railway, and National Rail services within London.[178] Fares for single journeys are cheaper than paper tickets, and a daily cap limits the total cost in a day to the price of a Day Travelcard.[179] The Oyster card must be 'touched in' at the start and end of a journey, otherwise it is regarded as 'incomplete' and the maximum fare charged.[180] In March 2012 the cost of this in the previous year to travellers was £66.5 million.[181] Contactless payment cards can be used instead of an Oyster card on buses, and this was extended to London Underground, London Overground, DLR and most National Rail services in London from 16 September 2014. The use of these has grown very quickly and now over a million contactless transactions are made on the Underground every day.[81]

A concessionary fare scheme is operated by London Councils for residents who are disabled or meet certain age criteria.[182] Residents born before 1951 were eligible after their 60th birthday, whereas those born in 1955 will need to wait until they are 66.[183] Called a "Freedom Pass" it allows free travel on TfL-operated routes at all times and is valid on some National Rail services within London at weekends and after 09:30 on Monday to Fridays.[184] Since 2010, the Freedom Pass has included an embedded holder's photograph; it lasts five years between renewals.[185]

In addition to automatic and staffed faregates at stations, the Underground also operates on a proof-of-payment system. The system is patrolled by both uniformed and plain-clothes fare inspectors with hand-held Oyster-card readers. Passengers travelling without a valid ticket must pay a penalty fare of £80 (or £40 if paid within 21 days) and can be prosecuted for fare evasion under the Regulation of Railways Act 1889 and Transport for London Byelaws.[186][187]

Hours of operation

The tube closes overnight. The first trains run from about 05:00 and the last trains until just after 01:00, with later starting times at weekends.[188][189] The nightly closures are used for maintenance,[188] but some lines stay open on New Year's Eve[190] and run for longer hours during major public events such as the 2012 London Olympics.[191] Some lines are occasionally closed for scheduled engineering work at weekends.[192]

The Underground runs a limited service on Christmas Eve with some lines closing early, and does not operate on Christmas Day.[190] Since 2010 a dispute between London Underground and trade unions over holiday pay has resulted in a limited service on Boxing Day.[193]

Night Tube

On 19 August 2016, London Underground launched a 24-hour service on the Victoria and Central lines with plans in place to extend this to the Piccadilly, Northern and Jubilee lines in the autumn starting on Friday morning and continuing right through until Sunday evening. This was originally scheduled to start on 12 September 2015, following completion of upgrades, but in August 2015 it was announced that the start date for the Night Tube had been pushed back because of ongoing talks about contract terms between trade unions and London Underground.[194][195] On 23 May 2016 it was announced that the night service would launch on 19 August 2016 for the Central and Victoria lines. This will be extended to the Piccadilly, Jubilee and Northern lines in the autumn of 2016.[196] The service is intended to operate on the:

- Central line: between Ealing Broadway and Hainault via Newbury Park and between White City and Loughton. No service on West Ruislip Branch, between Woodford and Hainault or between Loughton and Epping.

- Northern line: between Morden and Edgware / High Barnet via Charing Cross. No service on Mill Hill East or Bank Branches.

- Piccadilly line: between Cockfosters and Heathrow Terminals 2, 3 and 5. No service to Terminal 4 or between Acton Town and Uxbridge.

- Jubilee line: Full line – Stratford to Stanmore.

- Victoria line: Full line – Wathamstow Central to Brixton.

The Jubilee, Piccadilly and Victoria lines will operate at 10-minute intervals, and the Central line between White City and Leytonstone, but will operate at 20-minute intervals from Leytonstone to Hainault/Loughton, and 20 minutes between White City and Ealing Broadway. The Northern line will operate at roughly 8-minute intervals between Morden and Camden Town via Charing Cross, and 15-minute intervals from Camden Town to Edgware/High Barnet.[197]

No services will operate on the other lines for the time being. When the upgrade of the Circle, Hammersmith & City, District and Metropolitan lines is complete and the new signalling system has been fully introduced, along with new trains, the Night Tube service will be extended to these lines.[198]

Accessibility

Accessibility for people with limited mobility was not considered when most of the system was built, and before 1993 fire regulations prohibited wheelchairs on the Underground. The stations on the Jubilee Line Extension, opened in 1999, were designed for accessibility, but retrofitting accessibility features to the older stations is a major investment that is planned to take over twenty years.[199] A 2010 London Assembly Report concluded that over 10% of people in London had reduced mobility[200] and, with an ageing population, numbers will increase in the future.[201]

The standard issue tube map indicates stations that are step-free from street to platforms. There can also be a step from platform to train as large as 12 inches (300 mm) and a gap between the train and curved platforms, and these distances are marked on the map. Access from platform to train at some stations can be assisted using a boarding ramp operated by staff, and a section has been raised on some platforms to reduce the step.[202][203]

As of December 2012 there are 66 stations with step-free access from platform to train,[204] and there are plans to provide step-free access at another 28 in ten years.[205] By 2016 a third of stations are to have platform humps that reduce the step from platform to train.[206] New trains, such as those being introduced on the sub-surface network, have access and room for wheelchairs, improved audio and visual information systems and accessible door controls.[206][104]

Delays and overcrowding

During peak hours, stations can get so crowded that they need to be closed. Passengers may not get on the first train[207] and the majority of passengers do not find a seat on their trains,[208] some trains having more than four passengers every square metre.[209] When asked, passengers report overcrowding as the aspect of the network that they are least satisfied with, and overcrowding has been linked to poor productivity and potential poor heart health.[210] Capacity increases have been overtaken by increased demand, and peak overcrowding has increased by 16 per cent since 2004/5.[211]

Compared with 2003/4, the reliability of the network had increased in 2010/11, with Lost Customer Hours reduced from 54 million to 40 million.[212] Passengers are entitled to a refund if their journey is delayed by 15 minutes or more due to circumstances within the control of TfL,[213] and in 2010, 330,000 passengers of a potential 11 million Tube passengers claimed compensation for delays.[214] A number of mobile phone apps and services have been developed to help passengers claim their refund more efficiently.[215]

Safety

London Underground is authorised to operate trains by the Office of Rail Regulation, and the latest Safety Certification and Safety Authorisation is valid until 2017.[216] As at 19 March 2013 there had been 310 days since the last major incident,[217] when a passenger had died after falling on the track.[218] As of 2015 there have been nine consecutive years in which no employee fatalities have occurred.[219]

In November 2011 it was reported that 80 people had committed suicide in the previous year on the London Underground, up from 46 in 2000.[220] Most platforms at deep tube stations have pits, often referred to as 'suicide pits', beneath the track. These were constructed in 1926 to aid drainage of water from the platforms, but halve the likelihood of a fatality when a passenger falls or jumps in front of a train.[221][222][223]

Design and the arts

Map

Early maps of the Metropolitan and District railways were city maps with the lines superimposed,[224] and the District published a pocket map in 1897.[225] A Central London Railway route diagram appears on a 1904 postcard and 1905 poster,[226] similar maps appearing in District Railway cars in 1908.[227] In the same year, following a marketing agreement between the operators, a joint central area map that included all the lines was published.[228][229] A new map was published in 1921 without any background details, but the central area was squashed, requiring smaller letters and arrows.[230] Harry Beck had the idea of expanding this central area, distorting geography, and simplifying the map so that the railways appeared as straight lines with equally spaced stations. He presented his original draft in 1931, and after initial rejection it was first printed in 1933. Today's tube map is an evolution of that original design, and the ideas are used by many metro systems around the world.[231][232]

The current standard tube map shows the Docklands Light Railway, London Overground, Emirates Air Line, London Tramlink and the London Underground;[233] a more detailed map covering a larger area, published by National Rail and Transport for London, includes suburban railway services.[171] The tube map came second in a BBC and London Transport Museum poll asking for a favourite UK design icon of the 20th century[234] and the underground's 150th anniversary was celebrated by a Google Doodle on the search engine.[235][236]

Roundel

While the first use of a roundel in a London transport context was the trademark of the London General Omnibus Company registered in 1905, it was first used on the Underground in 1908 when the UERL placed a solid red circle behind station nameboards on platforms to highlight the name.[237][238] The word "UNDERGROUND" was placed in a roundel instead of a station name on posters in 1912 by Charles Sharland and Alfred France, as well as on undated and possibly earlier posters from the same period.[239] Frank Pick thought the solid red disc cumbersome and took a version where the disc became a ring from a 1915 Sharland poster and gave it to Edward Johnston to develop, and registered the symbol as a trademark in 1917.[240] The roundel was first printed on a map cover using the Johnston typeface in June 1919, and printed in colour the following October.[241]

After the UERL was absorbed into the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933, it used forms of the roundel for buses, trams and coaches, as well as the Underground. The words "London Transport" were added inside the ring, above and below the bar. The Carr-Edwards report, published in 1938 as possibly the first attempt at a graphics standards manual, introduced stricter guidelines.[242] Between 1948 and 1957 the word "Underground" in the bar was replaced by "London Transport".[243] As of 2013, forms of the roundel, with differing colours for the ring and bar, is used for other TfL services, such as London Buses, Tramlink, London Overground, London River Services and Docklands Light Railway.[244] Crossrail, due to open in 2018, is to be identified with a roundel.[245] The 100th anniversary of the roundel was celebrated in 2008 by TfL commissioning 100 artists to produce works that celebrate the design.[246]

Architecture

Seventy of the 270 London Underground stations use buildings that are on the Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest, and five have entrances in listed buildings.[247] The Metropolitan Railway's original seven stations were inspired by Italianate designs, with the platforms lit by daylight from above and by gas lights in large glass globes.[248] Early District Railway stations were similar and on both railways the further from central London the station the simpler the construction.[249] The City & South London Railway opened with red-brick buildings, designed by Thomas Phillips Figgis, topped with a lead-covered dome that contained the lift mechanism.[250] The Central London Railway appointed Harry Bell Measures as architect, who designed its pinkish-brown steel-framed buildings with larger entrances.[251]

In the first decade of the 20th century Leslie Green established a house style for the tube stations built by the UERL, which were clad in ox-blood faience blocks.[252] Green pioneered using building design to guide passengers with direction signs on tiled walls, with the stations given a unique identity with patterns on the platform walls.[253][254] Many of these tile patterns survive, though a significant number of these are now replicas.[255] Harry W. Ford was responsible for the design of at least 17 UERL and District Railway stations, including Barons Court and Embankment, and claimed to have first thought of enlarging the U and D in the UNDERGROUND wordmark.[256] The Met's architect Charles Walter Clark had used a neo-classical design for rebuilding Baker Street and Paddington Praed Street stations before World War I and, although the fashion had changed, continued with Farringdon in 1923. The buildings had metal lettering attached to pale walls.[251] Clark would later design "Chiltern Court", the large, luxurious block of apartments at Baker Street, that opened in 1929.[257] In the 1920s and 1930s, Charles Holden designed a series of modernist and art-deco stations some of which he described as his 'brick boxes with concrete lids'.[258] Holden's design for the Underground's headquarters building at 55 Broadway included avant-garde sculptures by Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill and Henry Moore.[259][260]

When the Central line was extended east, the stations were simplified Holden proto-Brutalist designs,[261] and a cavernous concourse built at Gants Hill in honour of early Moscow Metro stations.[262] Few new stations were built in the 50 years after 1948, but Misha Black was appointed design consultant for the 1960s Victoria line, contributing to the line's uniform look,[263] with each station having an individual tile motif.[264] Notable stations from this period include Moor Park, the stations of the Piccadilly line extension to Heathrow and Hillingdon. The stations of the 1990s extension of the Jubilee line were much larger than before[265] and designed in a high-tech style by architects such as Norman Foster and Michael Hopkins, making extensive use of exposed metal plating.[266] West Ham station was built as a homage to the red brick tube stations of the 1930s, using brick, concrete and glass.

Many platforms have unique interior designs to help passenger identification. The tiling at Baker Street incorporates repetitions of Sherlock Holmes's silhouette[267] and at Tottenham Court Road semi-abstract mosaics by Eduardo Paolozzi feature musical instruments, tape machines and butterflies.[268] Robyn Denny designed the murals on the Northern line platforms at Embankment.[267]

Johnston typeface

The first posters used a number of type fonts, as was contemporary practice,[269] and station signs used sans serif block capitals.[270] The Johnston typeface was developed in upper and lower case in 1916, and a complete set of blocks, marked Johnston Sans, was made by the printers the following year.[271] A bold version of the capitals was developed by Johnston in 1929.[272] The Met changed to a serif letterform for its signs in the 1920s, used on the stations rebuilt by Clark.[273] However, Johnston was adopted systemwide after the formation of the LPTB in 1933 and the LT wordmark was applied to locomotives and carriages.[274] Johnston was redesigned, becoming New Johnston, for photo-typesetting in the early 1980s when Elichi Kono designed a range that included Light, Medium and Bold, each with its italic version. The typesetters P22 developed today's electronic version, sometimes called TfL Johnston, in 1997.[275]

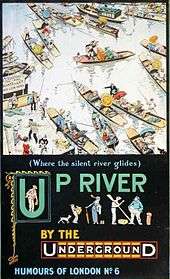

Posters and patron of the arts

Early advertising posters proclaimed the advantages of travelling using various letter forms.[276] Graphic posters first appeared in the 1890s,[277] and it became possible to print colour images economically in the early 20th century.[278] The Central London Railway used colour illustrations in their 1905 poster,[279] and from 1908 the underground group, under Pick's direction, used images of country scenes, shopping and major events on posters to encourage use of the tube.[280] Pick found he was limited by the commercial artists the printers used, and so commissioned work from artists and designers such as Dora Batty,[281] Edward McKnight Kauffer, the cartoonist George Morrow,[277] Herry (Heather) Perry,[281] Graham Sutherland,[277] Charles Sharland[282] and the sisters Anna and Doris Zinkeisen. According to Ruth Artmonsky, over 150 women artists were commissioned by Pick and latterly Christian Barman to design posters for London Underground, London Transport and London County Council Tramways.[283] The Johnston Sans letter form began appearing on posters from 1917.[282] The Met, strongly independent, used images on timetables and on the cover of its Metro-land guide that promoted the country it served for the walker, visitor and later the house-hunter.[284][285] By the time London Transport was formed in 1933 the UERL was considered a patron of the arts[277] and over 1000 works were commissioned in the 1930s, such as the cartoon images of Charles Burton and Kauffer's later abstract cubist and surrealist images.[286]

Harold Hutchison became London Transport publicity officer in 1947, after World War II and nationalisation, and introduced the "pair poster", where an image on a poster was paired with text on another. Numbers of commissions dropped, to eight a year in the 1950s and just four a year in the 1970s,[277] with images from artists such Harry Stevens and Tom Eckersley.[287] Art on the Underground was introduced in 1986 by Henry Fitzhugh to revive London Transport as a patron of the arts with the Underground commissioning six works a year,[277] judged first on artistic merit. In that year Peter Lee, Celia Lyttleton and a poster by David Booth, Malcolm Fowler and Nancy Fowler were commissioned.[288] Today commissions range from the pocket tube map cover to installations in a station.[289] Similarly, Poems on the Underground has commissioned poetry since 1986 that are displayed in carriages.[290]

In popular culture

The Underground (including several fictitious stations[291]) has been featured in many movies and television shows, including Skyfall, Die Another Day, Sliding Doors, An American Werewolf in London, Creep, Tube Tales and Neverwhere. The London Underground Film Office received over 200 requests to film in 2000.[292] The Underground has also featured in music such as The Jam's "Down in the Tube Station at Midnight" and in literature such as the graphic novel V for Vendetta. Popular legends about the Underground being haunted persist to this day.[293]

Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 has a level named Underground where most of the level takes place between the dockyards and Westminster while the player and a team of SAS attempt to take down cargo being shipped using London Underground. The London Underground map serves as a playing field for the conceptual game of Mornington Crescent[294] (which is named after a station on the Northern line) and the board game The London Game.

Notable people

- Charles Pearson (1793–1862) suggested an underground railway in London in 1845 and from 1854 promoted a scheme that eventually became the Metropolitan Railway.[295]

- John Fowler (1817–1898) was the railway engineer that designed the Metropolitan Railway.[296]

- Edward Watkin (1819–1901) was chairman of the Metropolitan Railway from 1872 to 1894.[297]

- James Henry Greathead (1844–1896) was the engineer that dug the Tower Subway using a method using a wrought iron shield patented by Peter W. Barlow, and later used the same tunnelling shield to build the deep-tube City & South London and Central London railways.[298][299]

- Charles Yerkes (1837–1905) was an American who founded the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) in 1902, which opened three tube lines and electrified the District Railway.[300][301]

- Edgar Speyer (1862–1932) Financial backer of Yerkes who served as UERL chairman from 1906 to 1915 during its formative years.[302]

- Albert Stanley (1874–1948) was manager of the UERL from 1907, and became the first chairman of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) in 1933.[303]

- Frank Pick (1878–1941) was UERL publicity officer from 1908, commercial manager from 1912 and joint managing director from 1928. He was chief executive and vice chairman of the LPTB from 1933 to 1940. It was Pick that commissioned Edward Johnston to create the typeface and redesign the roundel, and established the Underground's reputation as patrons of the arts as users of the best in contemporary poster art and architecture.[304]

- Robert Selbie (1868–1930) was manager of the Metropolitan Railway from 1908 until his death, marketing it using the Metro-land brand.[305][306]

- Edward Johnston (1872–1944) developed the Johnston Sans typeface, still in use today on the London Underground.[305]

- Harry Beck (1902–1974) designed the tube map, named in 2006 as a British design icon.[307]

- MacDonald Gill (1884–1947), cartographer credited with drawing, in 1914, "the map that saved the London Underground".

See also

- Automation of the London Underground

- List of busiest London Underground stations

- List of London Underground stations

- London Underground strikes

- Timeline of the London Underground

- Tube Challenge

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "About TfL – What we do – London Underground – Facts & figures". Transport for London. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Daily Ridership". London: Transport for London.

- 1 2 3 "Facts & Figures". London: Transport for London.

- ↑ "National Rail Enquiries - London Underground".

- ↑ Transport for London, Windsor House, 42–50 Victoria Street, London SW1H 0TL, [email protected]. "Facts & figures".

- ↑ Wolmar (2004), p. 135.

- 1 2 Croome & Jackson (1993), Preface.

- 1 2 3 Attwooll, Jolyon (5 August 2015). "London Underground: 150 fascinating Tube facts". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ "Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 2011/12" (PDF). TfL. pp. 98, 100. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

Fares revenue on LU was £2,410m... Operating expenditure on the Underground increased to £2,630m

- ↑ "Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 2011/12" (PDF). TfL. p. 11. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ Peacock (1970), pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 8.

- ↑ Jackson (1986), p. 19.

- ↑ Bextor, Robin (2013). A History of the London Underground. Demand Media Limited. p. 34. ISBN 1909217379.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 8, 14.

- ↑ Simpson (2003), p. 16.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 18–24.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 Day & Reed (2010), p. 26.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 33.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 32.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 40–45.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 52–56.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 50, 53.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 69–72, 78.

- 1 2 Green (1987), p. 30.

- ↑ Green (1987), pp. 24–28.

- ↑ Wolmar 2004, p. 204.

- ↑ Wolmar 2004, p. 205.

- ↑ Horne (2003), p. 51.

- ↑ Green (1987), p. 35.

- ↑ Green (1987), p. 33.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 94.

- 1 2 3 Day & Reed (2010), p. 122.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 84–88.

- ↑ Jackson (1986), pp. 134, 137.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 98–103, 111.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 110.

- 1 2 "Waterloo & City Line". Clive's Underground Line Guides. Clive Feather. 14 December 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Green (1987), p. 46.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 118.

- 1 2 Day & Reed (2010), p. 116.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 131, 133–134.

- ↑ Horne (2006), p. 73.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 135–136.

- ↑ "Bethnal Green Tube disaster marked 70 years on". BBC News. 3 March 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 150.

- 1 2 Cooke 1964, p. 739.

- ↑ Green (1987), p. 54.

- ↑ Green (1987), pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Green (1987), p. 56.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 163.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 160–162, 166–168, 171.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 172.

- ↑ "In Living Memory, Series 11: The 1975 Moorgate tube disaster". BBC Radio 4. 2 December 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ Green (1987), pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 178–181.

- ↑ Green (1987), pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Croome & Jackson (1993), p. 468.

- ↑ Fennell 1988, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Croome & Jackson (1993), pp. 474–476.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 206–211.

- 1 2 "About TfL – How we work – How we are governed – Subsidiary companies". Transport for London. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ↑ "Chief Officers". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014.

- ↑ "A brief history of the Underground – London Underground milestones". Transport for London. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 212–214.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), pp. 215, 221.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 216.

- 1 2 Rose (2007).

- ↑ "East London line officially opens". BBC News. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Circle Line extended to the west". BBC News. 5 March 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ Topham, Gwyn. "London tube introduces contactless payments". The Guardian. London.

- 1 2 "Contactless payment continues to grow in London". BBC News. 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "About TfL – What we do – London Underground". Transport for London. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ "East London Line opens to public". BBC. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Detailed London Transport Map". carto.metro.free.fr. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ↑ Croome & Jackson (1993), pp. 26, 33, 38, 81.

- ↑ Croome & Jackson (1993), pp. 327–328.

- ↑ Martin, Andrew (26 April 2012). Underground, Overground: A Passenger's History of the Tube. London: Profile Books. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-84765-807-4. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ London Underground. "Corporate identity—colour standards". Transport for London. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ↑ "Performance data almanac". Transport for London. 2014.

- ↑ Horne (2006), pp. 13, 24.

- ↑ Ovenden (2013), p. 220.

- 1 2 3 "Commissioner's Report" (PDF). Transport for London. 26 March 2014. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Railway Track Diagrams Vol. 5 (2nd ed.). Quail Map Company. 2002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Brown (2012).

- ↑ Table 115 National Rail timetable, May 13

- ↑ Maund, Richard (2013). Passenger Train Services over Unusual Lines.

- ↑ Peacock (1970), p. 67.

- ↑ Realtime Trains - East Putney

- ↑ "Rolling Stock". Transport for London. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 159.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 205.

- ↑ "Rolling Stock Data Sheet" (PDF). Transport for London. March 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 October 2013.

- 1 2 Connor, Piers (January 2013). "Deep tube transformation". Modern Railways. pp. 44–47.

- 1 2 "Making transport more accessible to all". Department for Transport. 3 October 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Hardy (2002), p. 6.

- 1 2 Croome & Jackson (1993), pp. 253–254.

- ↑ Griffiths, Emma (18 July 2006). "Baking hot at Baker Street". BBC News. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "London's Tube 'unfit for animals'". The Daily Telegraph. London. 28 August 2002. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ Croxford, Ben (4 December 2003). "Environmental Quality in Underground Railways". University College London. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ↑ Murray, Dick (23 August 2002). "Passengers choke on the Tube". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ Westgate, Stuart; Gilby, Mark (8 May 2007). "Meeting Report: Cooling the tube" (PDF). LURS. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "Water pump plan to cool the Tube". BBC News. 8 June 2006. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "Work begins to cool the platforms at two major central London stations" (Press release). Transport for London. 17 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Abbott, James (January 2013). "Sub-surface renewal". Modern Railways. pp. 38–41.

- ↑ Demartini, LC; Vielmo, HA; Möller, SV. "Numeric and experimental analysis of the turbulent flow through a channel with baffle plates". J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. & Eng. 2004, 26,.2.

- ↑ Croucher, S. "Deadly Asbestos 'All Over the Place' on London Underground". Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Croome & Jackson (1993), pp. 26, 35, 39, 87–89.

- ↑ Croome & Jackson (1993), p. 540.

- 1 2 3 Croome & Jackson (1993), pp. 114, 542.

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 59.

- ↑ Croome & Jackson (1993), pp. 154, 546.

- ↑ Malvern, Jack (21 October 2009). "Mystery over Tube escalator etiquette cleared up by restored film". The Times. London. (subscription required)

- ↑ Day & Reed (2010), p. 93.

- ↑ "Pioneers of Survival: Fire". PBS.

- ↑ "Incline lift at Greenford Tube station is UK first". Transport for London. 20 October 2015.

- ↑ "Step-free access". Transport for London. n.d. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013.