Treaty of Zadar

The Treaty of Zadar, also known as the Treaty of Zara, was a peace treaty signed in Zadar, Dalmatia on February 18, 1358 by which the Venetian Republic lost influence over its Dalmatian holdings. The Treaty of Zadar ended hostilities between Louis I of Hungary and the Republic of Venice, who were contesting control of a series of territories along the eastern Adriatic coastline in present-day Croatia.

Background

In 1301, the Árpád dynasty was dissolved and, following a brief interlude, was replaced by the Angevin dynasty as the rulers of Hungary and Croatia. The first Angevin king was Charles Robert, who ruled from 1312 to 1342. He was supported by the most powerful Croatian nobleman Pavao Šubić, Prince of Bribir and Ban (viceroy) of Croatia, ruler of the coastal cities of Split, Trogir, and Šibenik. Pavao became the Ban of Croatia, conferring on him many of the powers of a monarch including minting coinage, conferring charters on cities and levying annual taxes on them.

Pavao's actions led to a revolt among the Croatian nobility, who successfully reached out to King Charles to help them remove Pavaore. In exchange for his aide, however, the Croatian nobility was forced to declare their direct allegiance to the Hungarian monarchy, setting the stage for Hungarian attempts to expel the Venetian empire from the Croatian coastline.[1] While the other cities in the Dalmatian region were suffering from tug of war between the Venetians and the Hungarians and Croatians, Dubrovnik, which was held by Venice, was growing into an economic power house by exploiting its position between the west and the mineral-rich kingdoms of Serbia and Bosnia, as well as Dubrovnik's broader location between Europe and the Levant.[2]

In the 1350s the Hungarian monarch, Louis I, was able to assemble a force of 50,000 men by joining his forces with reinforcements sent by the Duke of Austria, the Counts of Gorizia, the Lord of Padua, Francesco I da Carrara, and the Patriarchate of Aquileia, a state within the Holy Roman Empire. In 1356, the coalition besieged the Venetians at Asolo, Conegliano, Ceneda and the stronghold of Treviso. At the same time, along the Dalmatian coast, the army had attacked the Hungarian-Croatian cities of Zadar, Trogir, Split and Dubrovnik. Although Trogir, Split and the other smaller towns surrendered fairly quickly, Zadar offered significant resistance to the Hungarian-led coalition.

Broken by a series of military reversals suffered in their own territory, the Venetians resigned themselves to the unfavorable conditions stipulated in the Treaty of Zadar, which was signed in the eponymous city on February 18, 1358.

Consequences

The treaty was signed in the Closter of Monastery of St. Francis and based on the terms of the agreement, the Dubrovnik region and Zadar came under the rule of the King of Hungary.[3][4] It marked the rise of the Republic of Ragusa as an independent and successful state. The same cannot be said for Zadar since it was later sold back to Venice by Ladislaus of Naples.[5]

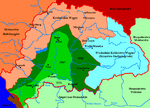

As a result of the peace treaty, Venice had to give all its possessions in Dalmatia to Hungary, from the Kvarner to the Bay of Kotor, but could keep the Istrian coast and the Treviso region. It was also forced to cancel, in the title of its doge, any reference to Dalmatia. However, the treaty preserved Venice's naval predominance in the Adriatic Sea as the King of Hungary accepted not to build a fleet of his own.

Louis of Hungary triumphantly entered Zadar in 1358 by granting extensive privileges to the nobility of Zadar and erecting the city capital of the kingdom of Dalmatia.

See also

References

- ↑ Goldstein, I:" Croatia; A History", page 27. Hurst & Company,London,1999.

- ↑ Tanner, M: "Croatia; A nation forged in war",page 25. Yale University Press, 1997.

- ↑ Lous I on Britannica Encyclopedia

- ↑ Louis I on Answers.com

- ↑ Ayton, Andrew (2005), The Realm of St. Stephen. A History of Medieval Hungary, 895 – 1526, pg. 162-163, London: Tauris, ISBN 1-85043-977-X

External links

- (Croatian) Zadarski list Kako je i zašto Ladislav prodao Dalmaciju, June 7, 2008