Treaty of Cahuenga

The Treaty of Cahuenga, also called the "Capitulation of Cahuenga," ended the fighting of the Mexican-American War in Alta California in 1847. It was not a formal treaty between nations but an informal agreement between rival military forces in which the Californios gave up fighting. The treaty was drafted in English and Spanish by José Antonio Carrillo, approved by American Lieutenant-Colonel John C. Frémont and Mexican Governor Andrés Pico on January 13, 1847 at Campo de Cahuenga in what is now North Hollywood, Los Angeles, California.

The treaty called for the Californios to give up their artillery, and provided that all prisoners from both sides be immediately freed. Those Californios who promised not to again take up arms during the war, and to obey the laws and regulations of the United States, were allowed to peaceably return to their homes and ranchos. They were to be allowed the same rights and privileges as were allowed to citizens of the United States, and were not to be compelled to take an oath of allegiance until a treaty of peace was signed between the United States and Mexico, and were given the privilege of leaving the country if they wished to do so.

Under the later Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, Mexico formally ceded Alta California and other territories to the United States, and the disputed border of Texas was fixed at the Rio Grande. Pico, like nearly all the Californios, became an American citizen with full legal and voting rights. Pico later became a State Assemblyman and then a State Senator representing Los Angeles in the California State Legislature.

Events leading to the agreement

On December 27, 1846, Fremont and the California Battalion, in their march south to Los Angeles, reached a deserted Santa Barbara and raised the American flag.[1] He occupied a hotel close to the adobe of Bernarda Ruiz de Rodriguez, a wealthy educated woman of influence and Santa Barbara town matriarch, who had four sons on the Mexican side. She asked for and was granted ten minutes of Fremont's time, which stretched to two hours; she advised him that a generous peace would be to his political advantage—one that included Pico's pardon, release of prisoners, equal rights for all Californians and respect of property rights.

Fremont later wrote, "I found that her object was to use her influence to put an end to the war, and to do so upon such just and friendly terms of compromise as would make the peace acceptable and enduring. ... She wished me to take into my mind this plan of settlement, to which she would influence her people; meantime, she urged me to hold my hand, so far as possible. ... I assured her I would bear her wishes in mind when the occasion came."[2][3] The next day, Bernarda accompanied Fremont as he continued the march south.

On January 8, 1847, Fremont arrived at San Fernando.[4] On January 10, the combined army of Commodore Robert Stockton and Brigadier General Stephen Kearny re-took Los Angeles with no resistance.[5] Fremont learned of the reoccupation the next day.[6] On January 12, Bernarda went alone to the camp of General Andres Pico and told him of the peace agreement she and Fremont had forged. Fremont and two of Pico's officers agreed to the terms for a surrender, and Articles of Capitulation were penned by Jose Antonio Carrillo in both English and Spanish .[7] The first seven articles in the treaty were nearly the verbatim suggestions offered by Bernarda Ruiz de Rodriguez.

On January 13, at a rancho at the north end of Cahuenga Pass, with Bernarda Ruiz de Rodriguez present, John Fremont, Andres Pico and six others signed the Articles of Capitulation, which became known as the Treaty of Cahuenga. This treaty, between the then-ranking US army officer in the area, and the then-Mexican military commander of the area, was made without the formal backing of either the American government in Washington, or of the Mexican government in Mexico City. Still, not only was it eventually honored by both national governments, it was immediately and permanently observed by the local American and Californio populations. Fighting ceased, thus ending the war in California.[8][9]

On January 14, the California Battalion entered Los Angeles in a rainstorm, and Fremont delivered the treaty to Commodore Robert Stockton.[10] Kearny and Stockton decided to accept the liberal terms offered by Frémont to terminate hostilities, despite Andres Pico having broken his earlier pledge that he would not fight U.S. forces. The next day Stockton approved the Treaty of Cahuenga in a message that he sent to the Secretary of the Navy.[11]

Historical re-enactment

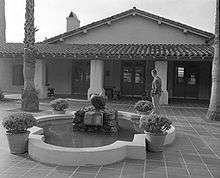

In celebration, on or around the date of the original signing, a historical ceremony is conducted at Campo de Cahuenga State Historic Park and site. From time to time, some of the descendants have appeared, along with actors to re-create this historical moment.

See also

- Cahuenga, California; Tongva settlement.

References

- ↑ Walker, Dale L. (1999). Bear Flag Rising: The Conquest of California, 1846. New York: Macmillan. p. 235. ISBN 0312866852.

- ↑ "Campo de Cahuenga, the Birthplace of California". Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ↑ "L.A. Then and Now: Woman Helped Bring a Peaceful End to Mexican-American War". Los Angeles Times. 5 May 2002.

- ↑ Walker p. 239

- ↑ Walker p. 242

- ↑ Walker p. 245

- ↑ Walker p. 246

- ↑ Walker p. 246

- ↑ Meares, Hadley (11 July 2014). "In a State of Peace and Tranquility: Campo de Cahuenga and the Birth of American California". Retrieved 24 Aug 2014.

- ↑ Walker p. 249

- ↑ Walker p. 249

External links

- Mark J. Denger, "The Treaty of Campo de Cahuenga"

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |