Cogeneration

| Part of a series about |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

| Energy conservation |

| Renewable energy |

| Sustainable transport |

|

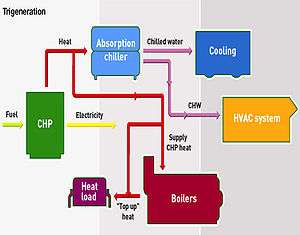

Cogeneration or combined heat and power (CHP) is the use of a heat engine[1] or power station to generate electricity and useful heat at the same time. Trigeneration or combined cooling, heat and power (CCHP) refers to the simultaneous generation of electricity and useful heating and cooling from the combustion of a fuel or a solar heat collector.

Cogeneration is a thermodynamically efficient use of fuel. In separate production of electricity, some energy must be discarded as waste heat, but in cogeneration some of this thermal energy is put to use. All thermal power plants emit heat during electricity generation, which can be released into the natural environment through cooling towers, flue gas, or by other means. In contrast, CHP captures some or all of the by-product for heating, either very close to the plant, or—especially in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe—as hot water for district heating with temperatures ranging from approximately 80 to 130 °C. This is also called combined heat and power district heating (CHPDH). Small CHP plants are an example of decentralized energy.[2] By-product heat at moderate temperatures (100–180 °C, 212–356 °F) can also be used in absorption refrigerators for cooling.

The supply of high-temperature heat first drives a gas or steam turbine-powered generator and the resulting low-temperature waste heat is then used for water or space heating as described in cogeneration. At smaller scales (typically below 1 MW) a gas engine or diesel engine may be used. Trigeneration differs from cogeneration in that the waste heat is used for both heating and cooling, typically in an absorption refrigerator. CCHP systems can attain higher overall efficiencies than cogeneration or traditional power plants. In the United States, the application of trigeneration in buildings is called building cooling, heating and power (BCHP). Heating and cooling output may operate concurrently or alternately depending on need and system construction.

Cogeneration was practiced in some of the earliest installations of electrical generation. Before central stations distributed power, industries generating their own power used exhaust steam for process heating. Large office and apartment buildings, hotels and stores commonly generated their own power and used waste steam for building heat. Due to the high cost of early purchased power, these CHP operations continued for many years after utility electricity became available.[3]

Overview

Thermal power plants (including those that use fissile elements or burn coal, petroleum, or natural gas), and heat engines in general, do not convert all of their thermal energy into electricity. In most heat engines, slightly more than half is lost as excess heat (see: Second law of thermodynamics and Carnot's theorem). By capturing the excess heat, CHP uses heat that would be wasted in a conventional power plant, potentially reaching an efficiency of up to 80%,[4] for the best conventional plants. This means that less fuel needs to be consumed to produce the same amount of useful energy.

Steam turbines for cogeneration are designed for extraction of steam at lower pressures after it has passed through a number of turbine stages, or they may be designed for final exhaust at back pressure (non-condensing), or both.[5] A typical power generation turbine in a paper mill may have extraction pressures of 160 psig (1.103 MPa) and 60 psig (0.41 MPa). A typical back pressure may be 60 psig (0.41 MPa). In practice these pressures are custom designed for each facility. The extracted or exhaust steam is used for process heating, such as drying paper, evaporation, heat for chemical reactions or distillation. Steam at ordinary process heating conditions still has a considerable amount of enthalpy that could be used for power generation, so cogeneration has lost opportunity cost. Conversely, simply generating steam at process pressure instead of high enough pressure to generate power at the top end also has lost opportunity cost. (See: Steam turbine#Steam supply and exhaust conditions) The capital and operating cost of high pressure boilers, turbines and generators are substantial, and this equipment is normally operated continuously, which usually limits self-generated power to large-scale operations.

Some tri-cycle plants have used a combined cycle in which several thermodynamic cycles produced electricity, then a heating system was used as a condenser of the power plant's bottoming cycle. For example, the RU-25 MHD generator in Moscow heated a boiler for a conventional steam powerplant, whose condensate was then used for space heat. A more modern system might use a gas turbine powered by natural gas, whose exhaust powers a steam plant, whose condensate provides heat. Tri-cycle plants can have thermal efficiencies above 80%.

The viability of CHP (sometimes termed utilisation factor), especially in smaller CHP installations, depends on a good baseload of operation, both in terms of an on-site (or near site) electrical demand and heat demand. In practice, an exact match between the heat and electricity needs rarely exists. A CHP plant can either meet the need for heat (heat driven operation) or be run as a power plant with some use of its waste heat, the latter being less advantageous in terms of its utilisation factor and thus its overall efficiency. The viability can be greatly increased where opportunities for Trigeneration exist. In such cases, the heat from the CHP plant is also used as a primary energy source to deliver cooling by means of an absorption chiller.

CHP is most efficient when heat can be used on-site or very close to it. Overall efficiency is reduced when the heat must be transported over longer distances. This requires heavily insulated pipes, which are expensive and inefficient; whereas electricity can be transmitted along a comparatively simple wire, and over much longer distances for the same energy loss.

A car engine becomes a CHP plant in winter when the reject heat is useful for warming the interior of the vehicle. The example illustrates the point that deployment of CHP depends on heat uses in the vicinity of the heat engine.

Thermally enhanced oil recovery (TEOR) plants often produce a substantial amount of excess electricity. After generating electricity, these plants pump leftover steam into heavy oil wells so that the oil will flow more easily, increasing production. TEOR cogeneration plants in Kern County, California produce so much electricity that it cannot all be used locally and is transmitted to Los Angeles.

CHP is one of the most cost-efficient methods of reducing carbon emissions from heating systems in cold climates [6] and is recognized to be the most energy efficient method of transforming energy from fossil fuels or biomass into electric power.[7] Cogeneration plants are commonly found in district heating systems of cities, central heating systems from buildings, hospitals, prisons and are commonly used in the industry in thermal production processes for process water, cooling, steam production or CO2 fertilization.

Types of plants

Topping cycle plants primarily produce electricity from a steam turbine. The exhausted steam is then condensed and the low temperature heat released from this condensation is utilized for e.g. district heating or water desalination.

Bottoming cycle plants produce high temperature heat for industrial processes, then a waste heat recovery boiler feeds an electrical plant. Bottoming cycle plants are only used when the industrial process requires very high temperatures such as furnaces for glass and metal manufacturing, so they are less common.

Large cogeneration systems provide heating water and power for an industrial site or an entire town. Common CHP plant types are:

- Gas turbine CHP plants using the waste heat in the flue gas of gas turbines. The fuel used is typically natural gas.

- Gas engine CHP plants use a reciprocating gas engine which is generally more competitive than a gas turbine up to about 5 MW. The gaseous fuel used is normally natural gas. These plants are generally manufactured as fully packaged units that can be installed within a plantroom or external plant compound with simple connections to the site's gas supply, electrical distribution network and heating systems. Typical outputs and efficiences see [8] Typical large example see [9]

- Biofuel engine CHP plants use an adapted reciprocating gas engine or diesel engine, depending upon which biofuel is being used, and are otherwise very similar in design to a Gas engine CHP plant. The advantage of using a biofuel is one of reduced hydrocarbon fuel consumption and thus reduced carbon emissions. These plants are generally manufactured as fully packaged units that can be installed within a plantroom or external plant compound with simple connections to the site's electrical distribution and heating systems. Another variant is the wood gasifier CHP plant whereby a wood pellet or wood chip biofuel is gasified in a zero oxygen high temperature environment; the resulting gas is then used to power the gas engine. Typical smaller size biogas plant see [10]

- Combined cycle power plants adapted for CHP

- Molten-carbonate fuel cells and solid oxide fuel cells have a hot exhaust, very suitable for heating.

- Steam turbine CHP plants that use the heating system as the steam condenser for the steam turbine.

- Nuclear power plants, similar to other steam turbine power plants, can be fitted with extractions in the turbines to bleed partially expanded steam to a heating system. With a heating system temperature of 95 °C it is possible to extract about 10 MW heat for every MW electricity lost. With a temperature of 130 °C the gain is slightly smaller, about 7 MW for every MWe lost.[11]

Smaller cogeneration units may use a reciprocating engine or Stirling engine. The heat is removed from the exhaust and radiator. The systems are popular in small sizes because small gas and diesel engines are less expensive than small gas- or oil-fired steam-electric plants.

Some cogeneration plants are fired by biomass,[12] or industrial and municipal solid waste (see incineration). Some CHP plants utilize waste gas as the fuel for electricity and heat generation. Waste gases can be gas from animal waste, landfill gas, gas from coal mines, sewage gas, and combustible industrial waste gas.[13]

Some cogeneration plants combine gas and solar photovoltaic generation to further improve technical and environmental performance.[14] Such hybrid systems can be scaled down to the building level[15] and even individual homes.[16] More recent results show that solar photovoltaic + battery + CHP hybrid systems are technically viable in the continental U.S. to reduce consumer costs,[17] while reducing energy- and electricity-related greenhouse gas emissions.[18]

MicroCHP

Micro combined heat and power or 'Micro cogeneration" is a so-called distributed energy resource (DER). The installation is usually less than 5 kWe in a house or small business. Instead of burning fuel to merely heat space or water, some of the energy is converted to electricity in addition to heat. This electricity can be used within the home or business or, if permitted by the grid management, sold back into the electric power grid.

Delta-ee consultants stated in 2013 that with 64% of global sales the fuel cell micro-combined heat and power passed the conventional systems in sales in 2012.[19] 20.000 units were sold in Japan in 2012 overall within the Ene Farm project. With a Lifetime of around 60,000 hours. For PEM fuel cell units, which shut down at night, this equates to an estimated lifetime of between ten and fifteen years.[20] For a price of $22,600 before installation.[21] For 2013 a state subsidy for 50,000 units is in place.[20]

The development of small-scale CHP systems has provided the opportunity for in-house power backup of residential-scale photovoltaic (PV) arrays.[16] The results of a 2011 study show that a PV+CHP hybrid system not only has the potential to radically reduce energy waste in the status quo electrical and heating systems, but it also enables the share of solar PV to be expanded by about a factor of five.[16] In some regions, in order to reduce waste from excess heat, an absorption chiller has been proposed to utilize the CHP-produced thermal energy for cooling of PV-CHP system. [22] These trigeneration+photovoltaic systems have the potential to save even more energy and further reduce emissions compared to conventional sources of power, heating and cooling.[23]

MicroCHP installations use five different technologies: microturbines, internal combustion engines, stirling engines, closed cycle steam engines and fuel cells. One author indicated in 2008 that MicroCHP based on Stirling engines is the most cost effective of the so-called microgeneration technologies in abating carbon emissions;[24] A 2013 UK report from Ecuity Consulting stated that MCHP is the most cost-effective method of utilising gas to generate energy at the domestic level.[25][26] however, advances in reciprocation engine technology are adding efficiency to CHP plant, particularly in the biogas field.[27] As both MiniCHP and CHP have been shown to reduce emissions [28] they could play a large role in the field of CO2 reduction from buildings, where more than 14% of emissions can be saved using CHP in buildings.[29] The ability to reduce emissions is particularly strong for new communities in emission intensive grids that utilize a combination of CHP and photovoltaic systems.[30]

Trigeneration

A plant producing electricity, heat and cold is called a trigeneration[31] or polygeneration plant. Cogeneration systems linked to absorption chillers use waste heat for refrigeration.[32]

Combined heat and power district heating

In the United States, Consolidated Edison distributes 66 billion kilograms of 350 °F (180 °C) steam each year through its seven cogeneration plants to 100,000 buildings in Manhattan—the biggest steam district in the United States. The peak delivery is 10 million pounds per hour (or approximately 2.5 GW).[33][34]

Industrial CHP

Cogeneration is still common in pulp and paper mills, refineries and chemical plants. In this "industrial cogeneration/CHP", the heat is typically recovered at higher temperatures (above 100 deg C) and used for process steam or drying duties. This is more valuable and flexible than low-grade waste heat, but there is a slight loss of power generation. The increased focus on sustainability has made industrial CHP more attractive, as it substantially reduces carbon footprint compared to generating steam or burning fuel on-site and importing electric power from the grid.

Utility pressures versus self generating industrial

Industrial cogeneration plants normally operate at much lower boiler pressures than utilities. Among the reasons are: 1) Cogeneration plants face possible contamination of returned condensate. Because boiler feed water from cogeneration plants has much lower return rates than 100% condensing power plants, industries usually have to treat proportionately more boiler make up water. Boiler feed water must be completely oxygen free and de-mineralized, and the higher the pressure the more critical the level of purity of the feed water.[5] 2) Utilities are typically larger scale power than industry, which helps offset the higher capital costs of high pressure. 3) Utilities are less likely to have sharp load swings than industrial operations, which deal with shutting down or starting up units that may represent a significant percent of either steam or power demand.

Heat recovery steam generators

A heat recovery steam generator (HRSG) is a steam boiler that uses hot exhaust gases from the gas turbines or reciprocating engines in a CHP plant to heat up water and generate steam. The steam, in turn, drives a steam turbine or is used in industrial processes that require heat.

HRSGs used in the CHP industry are distinguished from conventional steam generators by the following main features:

- The HRSG is designed based upon the specific features of the gas turbine or reciprocating engine that it will be coupled to.

- Since the exhaust gas temperature is relatively low, heat transmission is accomplished mainly through convection.

- The exhaust gas velocity is limited by the need to keep head losses down. Thus, the transmission coefficient is low, which calls for a large heating surface area.

- Since the temperature difference between the hot gases and the fluid to be heated (steam or water) is low, and with the heat transmission coefficient being low as well, the evaporator and economizer are designed with plate fin heat exchangers.

Comparison with a heat pump

A heat pump may be compared with a CHP unit, in that for a condensing steam plant, as it switches to produce heat, then electrical generation becomes unavailable, just as the power used in a heat pump becomes unavailable. Typically for every unit of electrical power lost, then about 6 units of heat are made available at about 90 °C. Thus CHP has an effective Coefficient of Performance (COP) compared to a heat pump of 6.[35] It is noteworthy that the unit for the CHP is lost at the high voltage network and therefore incurs no losses, whereas the heat pump unit is lost at the low voltage part of the network and incurs on average a 6% loss. Because the losses are proportional to the square of the current, during peak periods losses are much higher than this and it is likely that widespread (i.e. city-wide application of heat pumps) would cause overloading of the distribution and transmission grids unless they are substantially reinforced.

It is also possible to run a heat driven operation combined with a heat pump, where the excess electricity (as heat demand is the defining factor on utilization) is used to drive a heat pump. As heat demand increases, more electricity is generated to drive the heat pump, with the waste heat also heating the heating fluid.

Distributed generation

Trigeneration has its greatest benefits when scaled to fit buildings or complexes of buildings where electricity, heating and cooling are perpetually needed. Such installations include but are not limited to: data centers, manufacturing facilities, universities, hospitals, military complexes, and schools. Localized trigeneration has addition benefits as described by distributed generation. Redundancy of power in mission critical applications, lower power usage costs and the ability to sell electrical power back to the local utility are a few of the major benefits. Even for small buildings such as individual family homes trigeneration systems provide benefits over cogeneration because of increased energy utilization.[36] This increased efficiency can also provide significant reduced greenhouse gas emissions, particularly for new communities.[37]

Most industrial countries generate the majority of their electrical power needs in large centralized facilities with capacity for large electrical power output. These plants have excellent economies of scale, but usually transmit electricity long distances resulting in sizable losses, negatively affect the environment. Large power plants can use cogeneration or trigeneration systems only when sufficient need exists in immediate geographic vicinity for an industrial complex, additional power plant or a city. An example of cogeneration with trigeneration applications in a major city is the New York City steam system.

Thermal efficiency

Every heat engine is subject to the theoretical efficiency limits of the Carnot cycle. When the fuel is natural gas, a gas turbine following the Brayton cycle is typically used.[38] Mechanical energy from the turbine drives an electric generator. The low-grade (i.e. low temperature) waste heat rejected by the turbine is then applied to space heating or cooling or to industrial processes. Cooling is achieved by passing the waste heat to an absorption chiller.

Thermal efficiency in a trigeneration system is defined as:

Where:

- = Thermal efficiency

- = Total work output by all systems

- = Total heat input into the system

Typical trigeneration models have losses as in any system. The energy distribution below is represented as a percent of total input energy:[39]

- Electricity = 45%

- Heat + Cooling = 40%

- Heat Losses = 13%

- Electrical Line Losses = 2%

Conventional central coal- or nuclear-powered power stations convert only about 33% of their input heat to electricity.[40] The remaining 67% emerges from the turbines as low-grade waste heat with no significant local uses so it is usually rejected to the environment. These low conversion efficiencies strongly suggest that productive uses could be found for this waste heat, and in some countries these plants do collect byproduct heat that can be sold to customers.

But if no practical uses can be found for the waste heat from a central power station, e.g., due to distance from potential customers, then moving generation to where the waste heat can find uses may be of great benefit. Even though the efficiency of a small distributed electrical generator may be lower than a large central power plant, the use of its waste heat for local heating and cooling can result in an overall use of the primary fuel supply as great as 80%.[40] This provides substantial financial and environmental benefits.

Costs

Typically, for a gas-fired plant the fully installed cost per kW electrical is around £400/kW ($577 USD), which is comparable with large central power stations.[10]

See also Cost of electricity by source

History

Cogeneration in Europe

The EU has actively incorporated cogeneration into its energy policy via the CHP Directive. In September 2008 at a hearing of the European Parliament’s Urban Lodgment Intergroup, Energy Commissioner Andris Piebalgs is quoted as saying, “security of supply really starts with energy efficiency.”[41] Energy efficiency and cogeneration are recognized in the opening paragraphs of the European Union’s Cogeneration Directive 2004/08/EC. This directive intends to support cogeneration and establish a method for calculating cogeneration abilities per country. The development of cogeneration has been very uneven over the years and has been dominated throughout the last decades by national circumstances.

The European Union generates 11% of its electricity using cogeneration.[42] However, there is large difference between Member States with variations of the energy savings between 2% and 60%. Europe has the three countries with the world’s most intensive cogeneration economies: Denmark, the Netherlands and Finland.[43] Of the 28.46 TWh of electrical power generated by conventional thermal power plants in Finland in 2012, 81.80% was cogeneration.[44]

Other European countries are also making great efforts to increase efficiency. Germany reported that at present, over 50% of the country’s total electricity demand could be provided through cogeneration. So far, Germany has set the target to double its electricity cogeneration from 12.5% of the country’s electricity to 25% of the country’s electricity by 2020 and has passed supporting legislation accordingly.[45] The UK is also actively supporting combined heat and power. In light of UK’s goal to achieve a 60% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2050, the government has set the target to source at least 15% of its government electricity use from CHP by 2010.[46] Other UK measures to encourage CHP growth are financial incentives, grant support, a greater regulatory framework, and government leadership and partnership.

According to the IEA 2008 modeling of cogeneration expansion for the G8 countries, the expansion of cogeneration in France, Germany, Italy and the UK alone would effectively double the existing primary fuel savings by 2030. This would increase Europe’s savings from today’s 155.69 Twh to 465 Twh in 2030. It would also result in a 16% to 29% increase in each country’s total cogenerated electricity by 2030.

Governments are being assisted in their CHP endeavors by organizations like COGEN Europe who serve as an information hub for the most recent updates within Europe’s energy policy. COGEN is Europe’s umbrella organization representing the interests of the cogeneration industry.

The European public–private partnership Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking Seventh Framework Programme project ene.field deploys in 2017[47] up 1,000 residential fuel cell Combined Heat and Power (micro-CHP) installations in 12 states. Per 2012 the first 2 installations have taken place.[48][49][50]

Cogeneration in the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the Combined Heat and Power Quality Assurance (CHPQA) scheme regulates the combined production of heat and power. CHPQA was introduced in 1996. It defines, through calculation of inputs and outputs, "Good Quality CHP" in terms of the achievement of primary energy savings against conventional separate generation of heat and electricity. Compliance with CHPQA is required for cogeneration installations to be eligible for government subsidies and tax incentives.[51]

Cogeneration in the United States

Perhaps the first modern use of energy recycling was done by Thomas Edison. His 1882 Pearl Street Station, the world’s first commercial power plant, was a combined heat and power plant, producing both electricity and thermal energy while using waste heat to warm neighboring buildings.[52] Recycling allowed Edison’s plant to achieve approximately 50 percent efficiency.

By the early 1900s, regulations emerged to promote rural electrification through the construction of centralized plants managed by regional utilities. These regulations not only promoted electrification throughout the countryside, but they also discouraged decentralized power generation, such as cogeneration.

By 1978, Congress recognized that efficiency at central power plants had stagnated and sought to encourage improved efficiency with the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA), which encouraged utilities to buy power from other energy producers.

Diffusion

Cogeneration plants proliferated, soon producing about 8% of all energy in the United States.[53] However, the bill left implementation and enforcement up to individual states, resulting in little or nothing being done in many parts of the country.

The United States Department of Energy has an aggressive goal of having CHP constitute 20% of generation capacity by the year 2030. Eight Clean Energy Application Centers[54] have been established across the nation whose mission is to develop the required technology application knowledge and educational infrastructure necessary to lead "clean energy" (combined heat and power, waste heat recovery and district energy) technologies as viable energy options and reduce any perceived risks associated with their implementation. The focus of the Application Centers is to provide an outreach and technology deployment program for end users, policy makers, utilities, and industry stakeholders.

High electric rates in New England and the Middle Atlantic make these areas of the United States the most beneficial for cogeneration.[55][56]

Outside of the United States, energy recycling is more common. Denmark is probably the most active energy recycler, obtaining about 55% of its energy from cogeneration and waste heat recovery. Other large countries, including Germany, Russia, and India, also obtain a much higher share of their energy from decentralized sources.[53][57]

Applications in power generation systems

Non-renewable

Any of the following conventional power plants may be converted to a CCHP system:[58]

Renewable

- Solar power—both solar thermal and photovoltaic

- Biomass

- Fuel cell

- Any type of compressor or turboexpander, such as in compressed air energy storage

See also

- Air separation

- Carnot cycle

- Carnot method

- CHP Directive

- Cost of electricity by source

- Distributed generation (more general term encompassing CHP)

- District heating

- Electricity generation

- Electrification

- Energy policy of the European Union

- Environmental impact of electricity generation

- European Biomass Association

- Euroheat & Power

- Industrial gas

- Micro combined heat and power

- New York City steam system

- Rankine cycle

Further reading

- Steam, Its Generation and Use (35 ed.). Babcock & Wilson Company. 1913.

References

- ↑ Cogeneration and Cogeneration Schematic, www.clarke-energy.com, retrieved 26.11.11

- ↑ "What is Decentralised Energy?". The Decentralised Energy Knowledge Base.

- ↑ Hunter, Louis C.; Bryant, Lynwood (1991). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730-1930, Vol. 3: The Transmission of Power. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-08198-9.

- ↑ "Combined Heat and Power – Effective Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future" (PDF). Oak Ridge National Laboratory. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- 1 2 Steam-its generation and use. Babcock & Wilcox. (Numerous editions). Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Carbon footprints of various sources of heat – biomass combustion and CHPDH comes out lowest". Claverton Energy Research Group.

- ↑ "Cogeneration recognized to be the most energy efficient method of transforming energy". Viessmann.

- ↑ "Finning Caterpillar Gas Engine CHP Ratings". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ "Complete 7 MWe Deutz ( 2 x 3.5MWe) gas engine CHP power plant for sale". Claverton Energy Research Group.

- 1 2 "38% HHV Caterpillar Bio-gas Engine Fitted to Sewage Works - Claverton Group". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ http://www.elforsk.se/nyhet/seminarie/Elforskdagen%20_10/webb_varme/d_welander.pdf [swedish]

- ↑ "High cogeneration performance by innovative steam turbine for biomass-fired CHP plant in Iislami, Finland" (PDF). OPET. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ "Transforming Greenhouse Gas Emissions into Energy" (PDF). WIPO Green Case Studies, 2014. World Intellectual Property Organization. 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Oliveira, A.C.; Afonso, C.; Matos, J.; Riffat, S.; Nguyen, M.; Doherty, P. (2002). "A Combined Heat and Power System for Buildings driven by Solar Energy and Gas". Applied Thermal Engineering. 22 (6): 587–593. doi:10.1016/S1359-4311(01)00110-7.

- ↑ Yagoub, W.; Doherty, P.; Riffat, S. B. (2006). "Solar energy-gas driven micro-CHP system for an office building". Applied thermal engineering. 26 (14): 1604–1610. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2005.11.021.

- 1 2 3 Pearce, J. M. (2009). "Expanding Photovoltaic Penetration with Residential Distributed Generation from Hybrid Solar Photovoltaic + Combined Heat and Power Systems". Energy. 34: 1947–1954. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2009.08.012.

- ↑ Mundada, Aishwarya; Shah, Kunal; Pearce, Joshua M. (2016). "Levelized cost of electricity for solar photovoltaic, battery and cogen hybrid systems". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 57: 692–703. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.084.

- ↑ Shah, Kunal K.; Mundada, Aishwarya S.; Pearce, Joshua M. (2015). "Performance of U.S. hybrid distributed energy systems: Solar photovoltaic, battery and combined heat and power". Energy Conversion and Management. 105: 71–80. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2015.07.048.

- ↑ The fuel cell industry review 2013

- 1 2 "Latest Developments in the Ene-Farm Scheme". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ "Launch of New 'Ene-Farm' Home Fuel Cell Product More Affordable and Easier to Install - Headquarters News - Panasonic Newsroom Global". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Nosrat, A.; Pearce, J. M. (2011). "Dispatch Strategy and Model for Hybrid Photovoltaic and Combined Heating, Cooling, and Power Systems". Applied Energy. 88: 3270–3276. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.02.044. hdl:1974/6439.

- ↑ Nosrat, A.H.; Swan, L.G.; Pearce, J.M. (2013). "Improved Performance of Hybrid Photovoltaic-Trigeneration Systems Over Photovoltaic-Cogen Systems Including Effects of Battery Storage". Energy. 49: 366–374. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2012.11.005.

- ↑ "What is Microgeneration? And what is the most cost effective in terms of CO2 reduction". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ The role of micro CHP in a smart energy world

- ↑ Elsevier Ltd, The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, United Kingdom. "Micro CHP report powers heated discussion about UK energy future". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ "Best Value CHP, Combined Heat & Power and Cogeneration - Alfagy - Profitable Greener Energy via CHP, Cogen and Biomass Boiler using Wood, Biogas, Natural Gas, Biodiesel, Vegetable Oil, Syngas and Straw". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Pehnt, M (2008). "Environmental impacts of distributed energy systems—The case of micro cogeneration". Environmental science & policy. 11 (1): 25–37. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2007.07.001.

- ↑ http://alfagy.com/what-is-chp/133-kaarsberg-t-rfiskum-jromm-a-rosenfeld-j-koomey-and-wpteagan-1998-qcombined-heat-and-power-chp-or-cogeneration-for-saving-energy-and-carbon-in-commercial-buildingsq.html "Combined Heat and Power (CHP or Cogeneration) for Saving Energy and Carbon in Commercial Buildings."

- ↑ Nosrat, A.H.; Swan, L.G.; Pearce, J. M. "Simulations of greenhouse gas emission reductions from low-cost hybrid solar photovoltaic and cogeneration systems for new communities". Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 8: 34–41. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2014.06.008.

- ↑ "Clarke Energy - Fuel-Efficient Distributed Generation". Clarke Energy. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Fuel Cells and CHP Archived May 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Newsroom: Steam". ConEdison. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Bevelhymer, Carl (2003-11-10). "Steam". Gotham Gazette. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Lowe, R. (2011). "Combined heat and power considered as a virtual steam cycle heat pump". Energy Policy. 39 (9): 5528–5534. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.05.007.

- ↑ Nosrat, A.H.; Swan, L.G.; Pearce, J.M. "Improved Performance of Hybrid Photovoltaic-Trigeneration Systems Over Photovoltaic-Cogen Systems Including Effects of Battery Storage". Energy. 49: 366–374. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2012.11.005.

- ↑ Nosrat, Amir H.; Swan, Lukas G.; Pearce, Joshua M. "Simulations of greenhouse gas emission reductions from low-cost hybrid solar photovoltaic and cogeneration systems for new communities". Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 8: 34–41. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2014.06.008.

- ↑ Hodge, B.K. (2009). Alternative Energy Systems & Applications. New York: Wiley-IEEE Press.

- ↑ "Trigeneration Systems with Fuel Cells" (PDF). Research Paper. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- 1 2 "DOE – Fossil Energy: How Turbine Power Plants Work". Fossil.energy.gov. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ↑ "Energy Efficiency Industrial Forum Position Paper: energy efficiency – a vital component of energy security" (PDF).

- ↑ 2011 - Cogen -Experts discuss the central role cogeneration has to play in shaping EU energy policy

- ↑ "COGEN Europe: Cogeneration in the European Union's Energy Supply Security" (PDF).

- ↑ "Electricity Generation by Energy Source".

- ↑ "KWKG 2002".

- ↑ "DEFRA Action in the UK - Combined Heat and Power".

- ↑ 5th stakeholders general assembly of the FCH JU

- ↑ "ene.field". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ European-wide field trials for residential fuel cell micro-CHP

- ↑ ene.field Grant No 303462 Archived November 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ UK DECC CHPQA website

- ↑ "World's First Commercial Power Plant Was a Cogeneration Plant". Cogeneration Technologies.

- 1 2 "World Survey of Decentralized Energy" (PDF). May 2006.

- ↑ Eight Clean Energy Application Centers

- ↑ "Electricity Data".

- ↑ "New England Energy".

- ↑ 'Recycling' Energy Seen Saving Companies Money. By David Schaper. May 22, 2008. Morning Edition. National Public Radio.

- ↑ Masters, Gilbert (2004). Renewable and efficient electric power systems. New York: Wiley-IEEE Press.