Tintin in America

| Tintin in America (Tintin en Amérique) | |

|---|---|

Cover of the English edition | |

| Date |

|

| Series | The Adventures of Tintin |

| Publisher | Le Petit Vingtième |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Hergé |

| Original publication | |

| Published in | Le Petit Vingtième |

| Date of publication | 3 September 1931 – 20 October 1932 |

| Language | French |

| Translation | |

| Publisher | Methuen |

| Date | 1973 |

| Translator |

|

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | Tintin in the Congo (1931) |

| Followed by | Cigars of the Pharaoh (1934) |

Tintin in America (French: Tintin en Amérique) is the third volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from September 1931 to October 1932 before being published in a collected volume by Éditions du Petit Vingtième in 1932. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy who travel to the United States, where Tintin reports on organised crime in Chicago. Pursuing a gangster across the country, he encounters a tribe of Blackfoot Native Americans before defeating the Chicago crime syndicate.

Following the publication of Tintin in the Congo, Hergé conducted research for a story set in the United States, desiring to reflect his concerns regarding the treatment of Native communities by the U.S. government. Bolstered by a publicity stunt, Tintin in America was a commercial success in Belgium and was soon republished in France. Hergé continued The Adventures of Tintin with Cigars of the Pharaoh, and the series became a defining part of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition. In 1945, Tintin in America was re-drawn and coloured in Hergé's ligne-claire style for republication by Casterman, with further alterations made at the request of his American publisher for a 1973 edition. The story was adapted for a 1991 episode of the Ellipse/Nelvana animated series The Adventures of Tintin. Critical reception of the work has been mixed, with commentators on The Adventures of Tintin arguing that although it represents an improvement on the preceding two instalments, it still reflects many of the problems that were visible in them.

Synopsis

In 1931, Tintin, a reporter for Le Petit Vingtième, goes with his dog Snowy on an assignment to Chicago, Illinois, to report on the city's organised crime syndicate. He is kidnapped by gangsters and brought before mobster boss Al Capone, whose criminal enterprises in the Congo were previously thwarted by Tintin. With Snowy's help, Tintin subdues his captors, but the police reject his claims, and the gangsters escape. After surviving attempts on his life, Tintin meets Capone's rival Bobby Smiles, who heads the Gangsters Syndicate of Chicago. Tintin is unpersuaded by Smiles' attempt to hire him, and after Tintin orchestrates the arrest of his gang, Smiles escapes and heads west.[1]

Tintin pursues Smiles to the Midwestern town of Redskin City. Here, Smiles convinces a tribe of Blackfeet Native Americans that Tintin is their enemy, and when Tintin arrives, he is captured and threatened with execution. After escaping, Tintin discovers a source of underground petroleum. The U.S. army then forces the Natives off their land, and oil companies build a city on the site within 24 hours. Tintin evades a lynch mob and a wildfire before discovering Smiles' remote hideaway cabin; after a brief altercation, he captures the gangster.[2]

Returning to Chicago with his prisoner, Tintin is praised as a hero, but gangsters kidnap Snowy and send Tintin a ransom note. Tracing the kidnappers to a local mansion, Tintin hides in a suit of armour and frees Snowy from the dungeon. The following day, Tintin is invited to a cannery, but it is a trap set by gangsters, who trick him into falling into the meat-grinding machine. Tintin is saved when the machine workers go on strike and then apprehends the mobsters. In thanks, he is invited to a banquet in his honour, where he is kidnapped and thrown into Lake Michigan to drown. Tintin survives by floating to the surface, but gangsters posing as police capture him. He once again overwhelms them, and hands them over to the authorities. Finally, Tintin's success against the gangsters is celebrated by a ticker-tape parade, following which he returns to Europe.[3]

History

Background

Georges Remi—best known under the pen name Hergé—was the editor and illustrator of Le Petit Vingtième ("The Little Twentieth"),[4] a children's supplement to Le Vingtième Siècle ("The Twentieth Century"), a conservative Belgian newspaper based in Hergé's native Brussels. Run by the Abbé Norbert Wallez, the paper described itself as a "Catholic Newspaper for Doctrine and Information" and disseminated a far-right, fascist viewpoint.[5] According to Harry Thompson, such political ideas were common in 1930s Belgium, and Hergé's milieu was permeated with conservative ideas revolving around "patriotism, Catholicism, strict morality, discipline, and naivety".[6]

In 1929, Hergé began The Adventures of Tintin comic strip for Le Petit Vingtième, about the exploits of fictional young Belgian reporter Tintin. Having been fascinated with the outdoor world of Scouting and the way of life he called "Red Indians" since boyhood, Hergé wanted to set Tintin's first adventure among the Native Americans in the United States.[7] However, Wallez ordered him to set his first adventure in the Soviet Union as a piece of anti-socialist propaganda for children (Tintin in the Land of the Soviets)[8] and the second had been set in the Belgian Congo to encourage colonial sentiment (Tintin in the Congo).[9]

Tintin in America was the third story in the series. At the time, the Belgian far right was deeply critical of the United States, as it was of the Soviet Union.[10] Wallez—and to a lesser degree Hergé—shared these opinions, viewing the country's capitalism, consumerism, and mechanisation as a threat to traditional Belgian society.[11] Wallez wanted Hergé to use the story to denounce American capitalism and had little interest in depicting Native Americans, which was Hergé's primary desire.[12] As a result, Tintin's encounter with the natives took up only a sixth of the narrative.[13] Hergé sought to demystify the "cruel savage" stereotype of the Natives that had been widely perpetuated in western films.[10] His depiction of the Natives was broadly sympathetic, yet he also depicted them as gullible and naïve, much as he had depicted the Congolese in the previous Adventure.[13]

Research

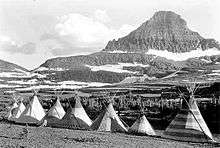

Hergé attempted greater research into the United States than he had done for the Belgian Congo or Soviet Union.[14] To learn more about Native Americans, Hergé read Paul Coze and René Thévenin's 1928 book Mœurs et histoire des Indiens Peaux-Rouges ("Customs and History of the Redskin Indians")[15] and visited Brussels' ethnographic museum.[16] As a result, his depiction of the Blackfoot Native Americans was "essentially accurate", with artefacts such as tipis and traditional costume copied from photographs.[16] To learn about Chicago and its gangsters, he read Georges Duhamel's 1930 book Scènes de la vie future ("Scenes from Future Life"). Written in the context of the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Duhamel's work contained strong anti-consumerist and anti-modernist sentiment, criticising the U.S.'s increased mechanisation and standardisation from a background of European conservatism; this would have resonated with both Wallez and Hergé's viewpoints. Many elements of Tintin in America, such as the abattoir scene, were adopted from Duhamel's descriptions.[17]

Hergé was also influenced by a special edition of radical anticonformist magazine Le Crapouillot (The Mortar Shell) that was published in October 1930. Devoted to the United States, it contained a variety of photographs that influenced his depiction of the country.[18] Hergé used its images of skyscrapers as a basis for his depiction of Chicago and adopted its account of Native Americans being evicted from their land when oil was discovered there.[19] He was particularly interested in the articles in the magazine written by reporter Claude Blanchard, who had recently travelled the U.S. He reported on the situation in Chicago and New York City and met with Native Americans in New Mexico.[20] Blanchard's article discussed the gangster George Moran, whom literary critic Jean-Marie Apostolidès believed provided the basis for the character Bobby Smiles.[21]

Hergé's depiction of the country was also influenced by American cinema,[22] and many of his illustrations were based on cinematic imagery.[23] Jean-Marc Lofficier and Randy Lofficier thought that Tintin's arrest of Smiles had been influenced by the Buffalo Bill stories, and that the idea of the gangsters taking Tintin away in their car came from Little Caesar.[24]

One of the individuals that Hergé could have learned about through Blanchard's article was the Chicago-based American gangster Al Capone.[22] In the preceding story, Tintin in the Congo, Capone had been introduced as a character within the series. There, he was responsible for running a diamond smuggling racket that Tintin exposed, setting up for further confrontation in Tintin in America.[13] Capone was one of only two real-life individuals to be named in The Adventures of Tintin,[22] and was the only real-life figure to appear as a character in the series.[24] In the original version, Hergé avoided depicting him directly, either illustrating the back of his head, or hiding his face behind a scarf; this was altered in the second version, in which Capone's face was depicted.[25] It is not known if Capone ever learned about his inclusion in the story,[26] although during initial serialisation he would have been preoccupied with his trial and ensuing imprisonment.[27]

Original publication, 1931–32

Tintin's in America began serialisation in Le Petit Vingtième on 3 September 1931, under the title of Les Aventures de Tintin, reporter, à Chicago (The Adventures of Tintin, Reporter, in Chicago). The use of "Chicago" over "America" reflected Wallez's desire for the story to focus on a critique of American capitalism and crime, for which the city was internationally renowned.[28] Part way through serialisation, as Tintin left Chicago and headed west, Hergé changed the title of the serial to Les Aventures de Tintin, reporter, en Amérique (The Adventures of Tintin, Reporter, in America).[29] The dog Snowy was given a diminished role in Tintin in America, which contained the last instance in the Adventures in which Tintin and Snowy have a conversation where they are able to understand each other.[30] In the banquet scene, a reference is made to a famous actress named Mary Pikefort, an allusion to the real-life actress Mary Pickford.[31] That same scene also featured a prototype for the character of Rastapopoulos, who was properly introduced in the following Cigars of the Pharaoh story.[32]

The strip's serialisation coincided with the publication of another of Hergé's comics set in the United States: Les aventures de "Tim" l'écureuil au Far-West (The Adventures of Tim the Squirrel Out West), published in sixteen instalments by the Brussels department store L'Innovation. Produced every Thursday, the series was reminiscent of Hergé's earlier Totor series.[33] Alongside these stories, Hergé was involved in producing his weekly Quick and Flupke comic strip and drawing front covers for Le Petit Vingtième, as well as providing illustrations for another of Le Vingtième Siècle's supplements, Votre "Vingtième" Madame, and undertaking freelance work designing advertisements.[27] In September 1931, part way through the story's serialisation, Hergé took a brief holiday in Spain with two friends, and in May 1932 was recalled to military service for two weeks.[34] On 20 July 1932, Hergé married Germaine Kieckens, who was Wallez's secretary. Although neither of them were entirely happy with the union, they had been encouraged to do so by Wallez, who demanded that all his staff marry and who personally carried out the wedding ceremony.[35] After a honeymoon in Vianden, Luxembourg, the couple moved into an apartment in the rue Knapen, Schaerbeek.[36]

As he had done with the prior two Adventures, Wallez organised a publicity stunt to mark the culmination of Tintin in America, in which an actor portraying Tintin arrived in Brussels.[26] It proved the most popular yet.[26] In 1932, the series was collected and published in a single volume by Les Éditions de Petit Vingtième,[37] coinciding with their publication of the first collected volume of Quick and Flupke.[38] A second edition was produced in France by Éditions Ogéo-Cœurs-Vaillants in 1934, while that same year Casterman published an edition, the first of The Adventures of Tintin that they released.[39] In 1936, Casterman asked Hergé to add several new colour plates to a reprint of Tintin in America, which he agreed to. They also asked him to replace the cover with one depicting a car chase, but he refused.[29]

Second version, 1945

In the 1940s, when Hergé's popularity had increased, he redrew many of the original black-and-white Tintin adventures in colour using the ligne claire ("clear line") drawing style he had developed, so that they visually fitted in with the newer Tintin stories. Tintin in America was reformatted and coloured in 1945[39] and saw publication in 1946.[13]

Various changes were made in the second edition. Some of the social commentary regarding the poor treatment of Native Americans by the government was toned down.[13] The name of the Native tribe was changed from the Orteils Ficelés ("Tied Toes") to the Pieds Noirs ("Black Feet").[24] Perhaps because Al Capone's power had diminished in the intervening years, Hergé depicted Capone's scarred face in the 1945 version.[24] He removed the reference to Mary Pikeford from the ceremonial dinner scene and deleted two Chinese hoodlums who tried to eat Snowy.[40] References to Belgium were also removed, allowing the story to have a greater international appeal.[19]

Later alterations and releases

When the second version of the story was translated into English by Michael Turner and Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper, they made a number of alterations to the text. For instance, Monsieur Tom Hawake, whose name was a pun on tomahawk, was renamed Mr. Maurice Oyle, and the Slift factory was renamed Grynd Corp.[41] Other changes were made to render the story more culturally understandable to an Anglophone readership; whereas the factory originally sold its mix of dogs, cats, and rats as hare pâté—a food uncommon in Britain—the English translation rendered the mix as salami.[41] In another instance, garlic, pepper, and salt were added to the mixture in the French version, but this was changed to mustard, pepper, and salt for the English version, again reflecting British culinary tastes.[41]

In 1957, Hergé considered sending Tintin back to North America for another adventure featuring the indigenous people. He decided against it, instead producing Tintin in Tibet.[42] Although Tintin in America and much of Hergé's earlier work displayed anti-American sentiment, he later grew more favourable to American culture, befriending one of the country's most prominent artists, Andy Warhol.[43] Hergé himself would first visit the United States in 1971, accompanied by his second wife Fanny Rodwell, and meet Edgar Red Cloud, the great grandson of the warrior chief Red Cloud. With a letter of recommendation from his friend Father Gall, he was invited to indulge his childhood desire to meet with real "Red Indians"—members of the Oglala Lakota on their Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota—and take part in a pow wow.[16]

American publishers of Tintin in America were uneasy regarding the scene in which the Blackfoot Natives are forcibly removed from their land. Hergé nevertheless refused to remove it.[44] For the 1973 edition published in the U.S., the publishers made Hergé remove African-American characters from the book, and redraw them as Caucasians or Hispanics, because they did not want to encourage racial integration among children.[45] That same year, the original black-and-white version was republished in a French-language collected volume with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Tintin in the Congo, the first part of the Archives Hergé collection.[39] In 1983, a facsimile of the original was published by Casterman.[39]

Critical analysis

Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier opined that Hergé had made "another leap forward" with Tintin in America, noting that while it still "rambles on", it is "more tightly plotted" than its predecessors.[24] They believed that the illustrations showed "marked progress" and that for the first time, several of the frames could be seen as "individual pieces of art".[46] Believing that it was the first work with the "intangible epic quality" they thought characterised The Adventures of Tintin, they awarded it two out of five stars.[46] They considered Bobby Smiles to be "the first great villain" of the series,[24] and also thought that an incompetent hotel detective featured in the comic was an anticipation of Thomson and Thompson, while another character, the drunken sheriff, anticipated Captain Haddock.[24] The Lofficiers believed that Hergé had successfully synthesised all of the "classic American myths" into a single narrative that "withstands comparison with the vision of America" presented in Gustave Le Rouge and Gustave Guitton's La Conspiration Des Milliardaires (The Billionaires' Conspiracy). They were of the opinion that Hergé's depiction of the exploitation of Native Americans was an "astonishing piece of narrative".[47]

Harry Thompson considered the story to be "little more than a tourist ramble" across the U.S., describing it as only "marginally more sophisticated" than its predecessors.[12] He nevertheless thought that it contained many indicators of "greater things",[30] remarking that Hergé's sympathy for the Natives was "a revolutionary attitude" for 1931.[48] Thompson also opined that the book's "highlight" was on page 29 of the 1945 version, in which oil is discovered on Native land, following which they are cleared off by the U.S. army, and a complete city is constructed on the site within 24 hours.[48] Biographer Benoît Peeters praised the strip's illustrations, feeling that they exhibited "a quality of lightness" and showed that Hergé was fascinated by the United States despite the anti-Americanism of his milieu.[49] He nevertheless considered it "in the same mode" as the earlier Adventures, calling it "a collection of clichés and snapshots of well-known places".[50] Elsewhere, Peeters commented that throughout the story, Tintin rushes around the country seeing as much as possible, likening him to the stereotypical American tourist.[51]

"Hergé paints a picture of 1930s America that is exciting, hectic, corrupt, fully automated and dangerous, one where the dollar is all powerful. It rings true enough, at least as much as the image projected by Hollywood at the time."

Michael Farr, 2001.[52]

Hergé biographer Pierre Assouline believed Tintin in America to be "more developed and detailed" than the prior Adventures,[22] representing the cartoonist's "greatest success" in a "long time".[10] Opining that the illustrations were "superior" due to Hergé's accumulated experience, he nevertheless criticised instances where the story exhibited directional problems; for instance, in one scene, Tintin enters the underground tunnel, but Assouline notes that while he is supposed to be travelling downward, he is instead depicted climbing up stairs.[10] Such directional problems were also criticised by Michael Farr,[19] who nevertheless thought the story "action-packed", with a more developed sense of satire and therefore greater depth than Soviets or Congo.[31] He considered the depiction of Tintin climbing along the ledge of the skyscraper on page 10 to be "one of the most remarkable" illustrations in the entire series, inducing a sense of vertigo in the reader.[43] He also opined that the depiction of the Blackfoot Natives being forced from their land was the "strongest political statement" in the series, illustrating that Hergé had "an acute political conscience" and was not the advocate of racial superiority that he has been accused of being.[13] Comparing the 1932 and 1945 versions of the comic, Farr believed that the latter was technically superior, but had lost the "freshness" of the original.[19]

Literary critic Jean-Marie Apostolidès of Stanford University thought that in Tintin in America, Hergé had intentionally depicted the wealthy industrialists as being very similar to the gangsters. He noted that this negative portrayal of capitalists continued into later Adventures of Tintin with characters such as Basil Barazov in The Broken Ear.[53] He considered this indicative of "a more ambivalent stance" to the right-wing agenda that Hergé had formerly adhered to.[21] Another literary critic, Tom McCarthy, concurred, believing that Tintin in America exhibited Hergé's "left-wing counter tendency" through attacking the racism and capitalist mass production of the U.S.[54] McCarthy believed that the work exposed social and political process as a "mere charade", much as Hergé had previously done in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets.[55]

Adaptations

Tintin in America was adapted into a 1991 episode of The Adventures of Tintin television series by French studio Ellipse and Canadian animation company Nelvana.[56] Directed by Stéphane Bernasconi, the character of Tintin was voiced by Thierry Wermuth.[56]

In 2002, French artist Jochen Gerner published a socio-political satire based on Tintin in America titled TNT en Amérique. It consisted of a replica of Hergé's book with most of the images blocked out with black ink; the only images left visible are those depicting violence, commerce, or divinity.[57] When interviewed as to this project, Gerner stated that his pervasive use of black was a reference to "the censure, to the night, the obscurity (the evil), the mystery of things not entirely revealed".[58]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Hergé 1973, pp. 1–16.

- ↑ Hergé 1973, pp. 17–43.

- ↑ Hergé 1973, pp. 44–62.

- ↑ Peeters 1989, pp. 31–32; Thompson 1991, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Peeters 1989, pp. 20–32; Thompson 1991, pp. 24–25; Assouline 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 24.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 40,46; Farr 2001, p. 29; Peeters 2012, p. 55.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 22–23; Peeters 2012, pp. 34–37.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 26–29; Peeters 2012, pp. 45–47.

- 1 2 3 4 Assouline 2009, p. 32.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 35; Peeters 2012, p. 56.

- 1 2 Thompson 1991, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Farr 2001, p. 29.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 55.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 30; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 28; Assouline 2009, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Farr 2001, p. 30.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, pp. 49–50; Farr 2001, pp. 33–35; Assouline 2009, p. 31; Peeters 2012, p. 55.

- ↑ Farr 2001, pp. 30, 35; Apostolidès 2010, pp. 21–22.

- 1 2 3 4 Farr 2001, p. 36.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 31; Peeters 2012, p. 55.

- 1 2 Apostolidès 2010, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Assouline 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ Farr 2001, pp. 30, 33; Peeters 2012, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 28.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 36; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Thompson 1991, p. 49.

- 1 2 Goddin 2008, p. 92.

- ↑ Peeters 1989, p. 36; Thompson 1991, p. 46; Assouline 2009, p. 31.

- 1 2 Goddin 2008, p. 96.

- 1 2 Thompson 1991, p. 50.

- 1 2 Farr 2001, p. 38.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 50; Farr 2001, p. 38.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 89.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, pp. 90, 104; Peeters 2012, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 49; Assouline 2009, pp. 33–34; Peeters 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 58.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 29; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 27.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 27.

- ↑ Farr 2001, pp. 36, 38; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Farr 2001, p. 35.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 46; Farr 2001, p. 30.

- 1 2 Farr 2001, p. 33.

- ↑ Peeters 1989, p. 36; Farr 2001, p. 29.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 48; Farr 2001, p. 38.

- 1 2 Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 29.

- ↑ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 28–29.

- 1 2 Thompson 1991, p. 47.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 56.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Peeters 1989, p. 36.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 39.

- ↑ Apostolidès 2010, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, p. 38.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, pp. 54–55.

- 1 2 Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 90.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, p. 186.

- ↑ Magma Books 2005.

Bibliography

- Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010) [2006]. The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults. Jocelyn Hoy (translator). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6031-7.

- Assouline, Pierre (2009) [1996]. Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Charles Ruas (translator). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

- Farr, Michael (2001). Tintin: The Complete Companion. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

- Goddin, Philippe (2008). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume I, 1907–1937. Michael Farr (translator). San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-706-8.

- Hergé (1973) [1945]. Tintin in America. Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner (translators). London: Egmont. ISBN 978-1-4052-0614-3.

- Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

- Magma Books (25 October 2005). "Jochen Gerner Interview". Magma Books. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013.

- McCarthy, Tom (2006). Tintin and the Secret of Literature. London: Granta. ISBN 978-1-86207-831-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (1989). Tintin and the World of Hergé. London: Methuen Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-416-14882-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (2012) [2002]. Hergé: Son of Tintin. Tina A. Kover (translator). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

- Thompson, Harry (1991). Tintin: Hergé and his Creation. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.

External links

- Tintin in America at the Official Tintin Website

- Tintin in America at Tintinologist.org