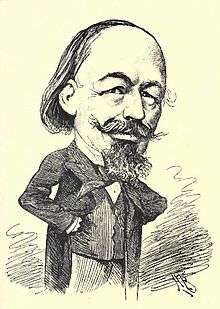

William Tinsley (publisher)

William Tinsley (13 July 1831 – 1 May 1902) was a British publisher. The son of a gamekeeper, he had little formal education; but together with his brother Edward (1835–1865) he founded the firm of Tinsley Brothers, which published many of the leading novelists of the time.

Life

Tinsley was born in the village of South Mimms, north of London, the second of ten children. Although his mother (born Sarah Dover, the daughter of a local vet)[1] could read and write well, his father William (born 1800), a gamekeeper,[2] did not value education, and his son only attended school for a few years. By the age of nine he was doing day jobs, such as bird scaring, in the fields.[3]

In 1852, at the age of seventeen, William's younger brother Edward moved to London to take up work in the Nine Elms engineers' workshop of the London and South Western Railway.[4] A few months later William followed him, walking from South Mimms to Notting Hill, where he quickly found work and lodging.[5] Both brothers were fond of books: William spent his evenings looking through bookshops and Edward quit his job with the railway to work for a small magazine Diogenes. In 1854 the brothers founded Tinsley Brothers, although the firm's formal foundation seems to date to 1858.[6] William, now an established businessman, married Louisa Rowley (1830 – 25 December 1899) on 26 April 1860. The couple would go on to have six daughters.[7]

After a slow start, the firm had its first major success with Mary Elizabeth Braddon's first novel Lady Audley's Secret in 1862.[8] The book was hugely profitable for Tinsley Brothers and started an association of the firm with sensation novels, continued in other novels by Mrs. Braddon, Ouida and Sheridan Le Fanu, and perhaps most significantly The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins.[9]

In 1866, Edward died of a stroke, leaving William to manage the firm alone.[10] He continued to publish new authors, with, most notably, the first books of Thomas Hardy and G. A. Henty and the first novels of Richard Jefferies.[11] In both Hardy's and Jefferies' case, he let the authors take a part of the risk, asking the former for £75, the latter for £60 to guarantee the costs. Hardy had brought Desperate Remedies (1871) to Tinsley because of the firm's reputation as a publisher of sensational novels;[12] but the book (like Jefferies' early novels) was not a success and Hardy regained only £59, 12s., 6d. from his original £75.[13] Despite this experience, Hardy returned to Tinsley with Under the Greenwood Tree (1872). Tinsley bought the copyright for £30, but again was unable to sell it. A Pair of Blue Eyes (1873) was yet another commercial failure; and later books by Hardy came out (more successfully) with other publishers.[14] In old age, Tinsley recounted that he never had the offer of Far from the Madding Crowd (1874);[15] but his assistant Edmund Downey remembered Tinsley telling him that Hardy had come to him detailing the rival offer:[16]

I thanked him very much and said,' Take the offer, my boy. I couldn't spring so much.' I seem to be very unlucky, Downey, about fourth novels, for the one I declined was ' Far From the Madding Crowd.' Of course, I hadn't seen it but even if I had it wouldn't have made any difference.

Shortly after his brother's death, Tinsley added a new venture to the firm, Tinsleys' Magazine. Shilling magazines were then very popular; and after failing to buy Temple Bar Magazine, Tinsley founded his own in 1867. The magazine published short fiction and serialisations of books that Tinsley Brothers were bringing out, including Hardy's A Pair of Blue Eyes.[17] The magazine ran from 1868 to 1884, edited first by the writer Edmund Yates, then by Tinsley, finally by Tinsley's assistant Edmund Downey. It was never a success and often had disastrous losses; but Tinsley saw it as a useful advertisement for the firm's books.[18]

The final decades of the firm were marked by repeated financial crises; and in 1887, Tinsley Brothers had liabilities of £1,000. The few books dated 1888 from the firm are presumably orders already placed with the printers before bankruptcy.[19] Tinsley survived his firm by fourteen years and towards the end was able to give a picture of Victorian publishing life in Random Recollections of an Old Publisher (1900). He died of chronic Bright's disease at his home in Wood Green on 1 May 1902.[20]

Tinsley was an unorthodox businessman, often working without formal agreements; and what he saw as fair dealing might come across as sharp practice to those who lost by it.[21] But he could also be generous and had a genuine enthusiasm for literature. His greatest passion was the theatre and his sometimes naive admiration led him to publish material from those involved in it against his own interest.[22]

Footnotes

- ↑ Newbolt (2001), 1.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 29–36.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 7–8.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 47–8; Newbolt (2001), 7.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 3; 42.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 46–9 gives 1854 as the start of the business; II, 343–4 cites a letter Tinsley wrote to the Athenaeum giving 1858 as the date and adding "I have our original agreement before me at this moment". Newbolt (2001), 31–2 discusses the patchy evidence for the brothers' early ventures.

- ↑ Newbolt (2001), 38; 196; Newbolt (2004).

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 56–8.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 82–5 (on Ouida). Newbolt (2001), 76–80 (on Ouida); 101–3 (on Le Fanu).

- ↑ Newbolt (2001), 95–8.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 126–7 (on Hardy); Downey (1905), 114–7 (on Henty); Miller and Matthews (1993), 91–3; 102–4; 113–5 (on Jefferies).

- ↑ Hardy (1928), 100, "By this time it seemed to have dawned upon him that the Macmillan publishing-house was not in the way of issuing novels of a sensational kind: and accordingly he packed up the MS. again and posted it to Messrs. Tinsley … which did publish such novels".

- ↑ Hardy (1928), 115–6; Purdy (1954), 4–5; Sutherland (1976), 218–22; Newbolt (2001), 156–62. Sutherland gives a transcription, Purdy and Newbolt a photo, of the account presented to Hardy. Purdy (1954), 329–35 also summarises the Hardy-Tinsley correspondence.

- ↑ Sutherland (1976), 222–5.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 128.

- ↑ Downey (1905), 20–1.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 128; Hardy (1928), 118.

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) 1, 323–4; Downey (1905), 242–72; Newbolt (2001), 203–16; Newbolt (2004).

- ↑ Newbolt (2001), 292–3.

- ↑ Newbolt (2004).

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 295 gives an example from his dealings with William Black: "There was no written agreement between us …, and I certainly thought I was entitled to charge what I had lost by 'Love or Marriage' out of the profit there was on 'In Silk Attire', but I reckoned without my host."

- ↑ Tinsley (1900) I, 47; Downey (1905), 215–6; Newbolt (2004).

References

- Downey, Edmund, Twenty Years Ago. London: Hurst and Blackett Ltd., 1905.

- Hardy, Frances Emily, The Early Life of Thomas Hardy 1840–1891. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1928.

- Miller, George and H. Matthews, Richard Jefferies: A Bibliographical Study. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1993. ISBN 0859679187.

- Newbolt, Peter, "Tinsley, William (1831–1902)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Accessed 22 May 2008.

- Newbolt, Peter, William Tinsley (1831–1902) "Speculative Publisher", A Commentary. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001. ISBN 0754602915.

- Purdy, Richard Little, Thomas Hardy: A bibliographical study. Oxford: OUP, 1954. Reprinted Delaware and London: Oak Knoll Press and British Museum, 2002. ISBN 1584560703

- Sutherland, J.A., Victorian Novelists and Publishers. London: Athlone Press, 1976. ISBN 0485111616.

- Tinsley, William. Random Recollections of an Old Publisher: Volume 1, Volume 2 (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd., 1900).

External links

- Anonymous (1873). Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day. Illustrated by Frederick Waddy. London: Tinsley Brothers. pp. 147–48. Retrieved 13 March 2011.