Thomas A. Scott

Thomas Alexander Scott (December 28, 1823 – May 21, 1881) was an American businessman, railroad executive, and industrialist. He was the fourth president of the Pennsylvania Railroad (1874-1880), later the largest publicly traded corporation in the world.

Scott was appointed in 1861 by President Abraham Lincoln as the U.S. Assistant Secretary of War during the American Civil War, and played a major role in using railroads in the war effort. He had a role in negotiating the Republican Party's Compromise of 1877 with the Democratic Party; it settled the disputed presidential election of 1876 in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes in exchange for the federal government pulling out its military forces from the South and ending the Reconstruction era.

History

Scott was born in 1823 in Peters Township near Fort Loudoun, in Franklin County, Pennsylvania.

Railroads

Scott joined the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1850 as a station agent, and by 1858 was general superintendent. Scott took a special interest in mentoring aspiring railroad employees, such as Andrew Carnegie. In 1860, Scott became the first Vice President of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The 1846 state charter to the Pennsylvania Railroad diffused power within the company, by giving executive authority to a committee responsible to stockholders, and not to individuals. By the 1870s, however, officers directed by J. Edgar Thomson and Scott had centralized power.[1]

Historians have explained the successful partnership of Thomas Scott and J. Edgar Thomson by the melding of their opposing personality traits: Thomson was the engineer, cool, deliberate, and introverted; Scott was the financier, daring, versatile, and a publicity-seeker.[2] In addition, they had common experiences and values, agreement on the importance of financial success, the financial stability of the Pennsylvania Railroad throughout their partnership, and J. Edgar Thomson's paternalism.[2] J. Edgar Thomson was the President of the Pennsylvania Railroad for more than three decades, from 1852 until his death in 1874.

In 1860, Scott became the first Vice President of the Pennsylvania Railroad. From 1871 to 1872, he was briefly the president of the Union Pacific Railroad, then the first transcontinental railroad owner. He was the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1874, upon the death of his partner Thomson, until 1880. The Pennsylvania Railroad expanded from a company of railway lines within Pennsylvania through the 1840s and 1850s, to a transportation empire from the 1860s onwards.[1]

Scott was notoriously secretive about his business dealings, conducting most of his business in private letters, and instructing his business partners to destroy them after they were read.[1]

After the Civil War, Scott was heavily involved in investments in the fast-growing trans-Mississippi River route into Texas, with long-term plans for a southern transcontinental railway line connecting the Southern states and California. However, the 1872 Crédit Mobilier scandal made Congress unwilling to grant railroad companies land grants in the west. The financial Panic of 1873 and subsequent economic depression made it impossible to finance Scott’s southern transcontinental railroad plans.

Civil War

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin called on Scott for his extensive knowledge of the rail and transportation systems of the state.[3] Scott received a staff commission as a colonel, and in August 1861, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Scott as Assistant Secretary of War.[3] The next year, he helped organize the Loyal War Governors' Conference in Altoona, Pennsylvania.[3]

Later on, Scott took on the task of equipping a substantial military force for the Union war effort.[3] He assumed supervision of government railroads and other transportation lines. He , and made the movement of supplies and troops more efficient and effective for the war effort on behalf of the Union. In one instance, he engineered the movement of 25,000 troops in 24 hours from Nashville, Tennessee, to Chattanooga, turning the tide of battle to a Union victory.[4]

Scott advised President Lincoln to travel covertly by rail to avoid Confederate spies and assassins.[3]

Reconstruction era

During the American Reconstruction in the aftermath of the Civil War, the Southern states needed their economy and infrastructure restored, and more investment in railroads. They had lagged behind the North in railroad miles. The Northern-based railroads competed to acquire routes and construct rail lines in the South. Federal assistance was sought by both special interest groups, but the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal made this difficult in 1872. Congress became unwilling to grant railroad companies land grants in the Southwestern United States.

In his "Scott Plan" of the later 1870s, Scott proposed that the largely Democratic Southern politicians would give their votes in Congress and state legislatures for federal government subsidies to various infrastructure improvements, including in particular the Texas and Pacific Railway, a scheme headed by Scott. Scott employed the expertise of Grenville Dodge in buying the support of newspaper editors as well as various politicians in order to build public support for the subsidies.

The Scott Plan became part of the Compromise of 1877, an informal and unwritten deal which settled the disputed Presidential election of 1876. However, it was never implemented, and railroad construction in the South remained at a low level after 1873 and its financial panic.[5]

Great Railroad Strike of 1877

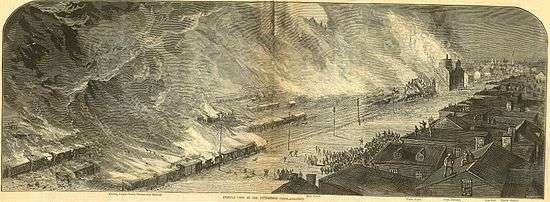

Despite Scott’s best efforts, the Pennsylvania Railroad continued to lose money through the 1870s. The oil magnate John D. Rockefeller had shifted much of his transportation of product for Standard Oil to his pipelines, causing severe problems for the rail industry. Scott still controlled the railway to Pittsburgh, where the pipelines of Rockefeller did not extend, but the two men were unable to come to terms on transportation costs. In response, Rockefeller closed his plants in Pittsburgh, forcing Scott to enact aggressive pay deductions of workers.[6]

In reaction, railroad workers went off the job and rioted in Pittsburgh; the city was the epicenter of the worst violence in the nation during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Scott, often referred to as one of the first robber barons of the Gilded Age, was quoted as saying that the strikers should be given "a rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread." [7]

Later life and legacy

Scott never recovered from the 1877 strike. The railroad-based economy of the United States was overtaken by the oil boom. Scott's protege Andrew Carnegie later challenged the Rockefeller monopoly in petroleum from his dominance of the steel industry. Just as the economy of railroads gave way to that of oil, oil in turn would face the emerging dominance of steel.[6] Scott's crucial business partner, J. Edgar Thomson, died in 1874. Scott suffered a stroke in 1878, limiting his ability to work.[2] He died on 21 May 1881, and was buried at Woodlands Cemetery in Philadelphia.

University of Pennsylvania Endowments

Scott was interested in education and health, and endowed certain positions at the University of Pennsylvania. His widow also made a variety of endowments in his name at the University of Pennsylvania, including:[8]

- Thomas A. Scott Fellowship in Hygiene

- Thomas A. Scott Professorship of Mathematics

- University Hospital: endowed beds for patients with chronic diseases.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Ward, James A. "Power and Accountability on the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1846-1878," Business History Review, Spring 1975, Vol. 49 Issue 1, pp 37–59

- 1 2 3 Ward, James A. "J. Edgar Thomson And Thomas A. Scott: A Symbiotic Partnership?," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, January 1976, Vol. 100 Issue 1, pp 37–65

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kamm, Samuel Richey, The Civil War Career of Thomas A. Scott, University of Pennsylvania, 1940.

- ↑ Roger Pickenpaugh, Rescue by Rail: Troop Transfer and the Civil War in the West, 1863 (University of Nebraska Press, 1998).

- ↑ Woodward, C. Vann. Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction, (1956)

- 1 2 Stephen David (2012). The Men Who Built America (DVD). The History Channel.

- ↑ Ingham, John N., Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders: N-U, Greenwood Press, 1983.

- ↑ Nitzsche, George Erasmus (1918), University of Pennsylvania: Its History, Traditions, Buildings and Memorials; Also a Brief Guide to Philadelphia (7th ed.), Philadelphia: International Printing Company, p. 155, OCLC 65488397

External links

- Richard White, "Corporations, Corruption, and the Modern Lobby: A Gilded Age Story of the West and the South in Washington, D.C.", Southern Spaces (April 2009).

- ted Nace, Gangs of America — Chapter 6, "The genius: The man who reinvented the corporation (1850-1880)"

- Furman.edu: "Re-Assessing Tom Scott, the 'Railroad Prince' "

- Ranknfile-ue.org: The Great Strike of 1877: Remembering a Worker Rebellion

- Thomas A. Scott at Find a Grave

| Business positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Oliver Ames, Jr. |

President of Union Pacific Railroad 1871–1872 |

Succeeded by Horace F. Clark |

| Preceded by J. Edgar Thomson |

President of Pennsylvania Railroad 1874 – 1880 |

Succeeded by George Brooke Roberts |