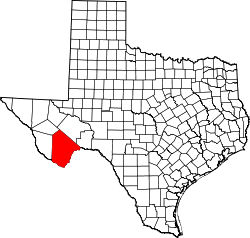

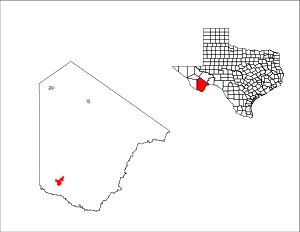

Terlingua, Texas

| Terlingua, Texas | |

|---|---|

| Census-designated place | |

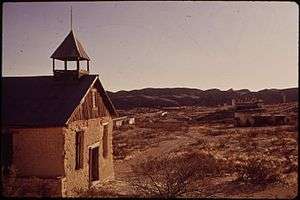

|

Terlingua in 1936 | |

| Nickname(s): Terlingua Ghost Town | |

| Motto: "The Texas Ghost Town" | |

| |

| Coordinates: 29°19′17″N 103°36′57″W / 29.32139°N 103.61583°WCoordinates: 29°19′17″N 103°36′57″W / 29.32139°N 103.61583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Brewster |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.0 sq mi (28.5 km2) |

| • Land | 11.0 sq mi (28.5 km2) |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 2,891 ft (881 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 58 |

| • Density | 5/sq mi (2.0/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| FIPS code | 48-72248[1] |

Terlingua (/tərˈlɪŋɡwə/ ter-LING-gwa) is a mining district and census-designated place (CDP) in southwestern Brewster County, Texas, United States. It is located near the Rio Grande and the villages of Lajitas and Study Butte, Texas, as well as the Mexican village of Santa Elena. The discovery of cinnabar, from which the metal mercury is extracted, in the mid-1880s brought miners to the area, creating a city of 2,000 people. The only remnants of the mining days are a ghost town of the Howard Perry-owned Chisos Mining Company and several nearby capped and abandoned mines, most notably the California Hill, the Rainbow, the 248, and the Study Butte mines. The mineral terlinguaite was first found in the vicinity of California Hill.

The population of Terlingua as of the 2010 census was 58.[2]

History

According to the historian Kenneth Baxter Ragsdale, "Facts concerning the discovery of cinnabar in the Terlingua area are so shrouded in legend and fabrication that it is impossible to cite the date and location of the first quicksilver recovery." The cinnabar was apparently known to Native Americans, who supposedly used its brilliant red color for pictographs.[3]

A man named Jack Dawson reportedly produced the first mercury from Terlingua in 1888, but the district got off to a slow start. The Terlingua finds did not begin to be publicized in newspapers and mining industry magazines until the mid-1890s.[4] By 1900, four mining companies had recovered 1000 flasks in the district: Lindheim and Dewees, Marfa and Mariposa, the California, and the Excelsior. By 1903, they were joined by the Texas Almaden Mining Company, the Big Bend Cinnabar Mining Company, and the Colquitt-Tigner combine.[3][5][6][7]

George W. Wanless and Charles Allen began working the area of California Mountain around 1894 based on reports of Mexican miners from as early as 1850. Ore was found in 1896. Jack Dawson, J.A. Davies and Louis Lindheim soon followed. A Terlingua post office was established in 1989 at the California Mountain mining community. The origin of the name Terlingua may be a corruption of Tres Lenguas, in reference to an early mine or local feature. By 1903, 3000 people populated the area. The mining center and post office eventually moved to the area of the Chisos Mine and the original settlement took on the name of Mariposa.[8]

Howard E. Perry

Born on 2 Nov. 1858 in Cleveland, Ohio, and worked for his father in the Woods-Perry Lumber Company until he was 21. Perry then moved to Chicago in 1881 and started work at C.M. Henderson, eventually rising to the position of director after his marriage to Grace Henderson on 2 Feb. 1897. In 1914 they moved to Portland, Maine.[3]:31–33

By 1887, Perry had acquired four sections in Texas, as security on an unpaid debt. Perry was offered increasingly more money for his property which prompted him to hire the attorney Eugene Cartledge to investigate. Cartledge determined the mining on adjoining property was actually infringing on the Perry property, through an error in a previous survey. Perry's attorneys filed a motion on 8 Nov. 1900, and Perry finally was granted legal possession on 13 May 1901 when the case was decided in his favor. Perry founded the Chisos Mining Company on 8 May 1903 with a $50,000 loan from the Austin National Bank, the same year the company reported its first recovery with two retorts.[3]:22–27

Two more retorts were added in 1904 and monthly production amounted to 200 flasks per month. In 1905, the company leased the Colquitt-Tigner 10-ton Scott furnace five miles away. In the same year, Perry hired Dr. William Battle Phillips (future director of the Texas Bureau of Economic Geology and President of the Colorado School of Mines), who taught Perry how to mine. In 1906 they agreed to install a 20-ton Scott furnace.[3]:38–42

The furnace was initially heated with mesquite and cottonwood. However, Perry hired the geologist Johan August Udden to prospect for coal on his property in 1926. The resultant coal was used to generate producer gas. Water was supplied by Mexican freighters hauling water from the Rio Grande twelve miles away. Some water was also obtained from a dam built on the Terlingua Creek. Water was also hauled ten miles from springs discovered in the Christmas Mountains and Cigar Mountain. By the mid-1920s, water came from the 800-foot level of the Chisos mine, which was pumped to the surface. Udden was also responsible for discovering the great ore body located in the limestone under the Del Rio Clay.[3]:54–64

Philipps departure in the autumn of 1906 began Perry's direct management of the mine. Remarkably he did this from his Chicago office. In essence, As Ragsdale notes, "Perry first perfected the technique of management in absentia" and "supervision-in-detail became the distinguishing feature of the Chicago-Terlingua correspondence." Perry also received semi-weekly telegraphed production reports. These reports and other correspondence used code books to maintain secrecy.[3]:62,68–69,71–72

In 1906, Perry built his Perry Mansion, based on the Moorish architecture from his visit to Almadén. The two story structure had nine bedrooms, a wine cellar, nine 10-foot arches, and a 90-foot front porch. By 1913, Perry had installed in Terlingua the Chisos Hotel, a "Company Store", an ice-making plant, telephone service, a company doctor, and mail delivery three times a week. By 1936 he had installed the Chisos Theatre and the Oasis Confectionery Shop. His mainly Mexican miners were provided rent-free dwellings. Perry joined the New York Yacht Club in 1920. He remained a member until 1944, owning during that time three different yachts, none smaller than 59 feet. In Perry's words, "If he had not wanted the yachts, he would not have made so much money, which he had to do in order to have them." As a consequence, Terlingua became the "Land of Perry", where he controlled all aspects of life.[3]:34,80–81,84,231,248,250

The beginning of the end to financial prosperity was in sight however by 1930. That is when Perry was forced into a $75,000 settlement with the adjoining Rainbow Mine. The Chisos Mine's No. 9 Shaft had been mining a rich ore body that extended two hundred feet into the Rainbow claim. Then in 1934, Perry was forced to increase wages in a settlement with the NRA. More disturbing were the accusations the mine was a "death trap" for miner safety. One of the Chisos geologists, A.R. Fletcher, later testified that the "mine was extremely hot, horribly hot, and there wasn't any provision made for ventilation."[3]:186–250,286

Financial problems with the Chisos mine were compounded when Perry bought the Mariposa mine in 1928 and then the Rainbow Mine in 1938. Though a major ore body in the Mariposa was found by Fletcher in 1935, by 1939 Fletcher reported that the Chisos Mine "had been worked out." Perry further squandered scarce cash on the Bonanza silver mine near Sierra Blanca, Texas, and the Stanley gold mine in Canada. With more accounts becoming delinquent, and creditors becoming more irate, Perry was forced into bankruptcy on 1 Oct. 1942. Perry died not long afterwards, on 6 Dec. 1944.[3]:252,259,270,274–275,279,294

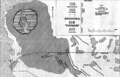

Geology

The regional geology is characterized by the Terlingua Uplift and the Solitario Dome. The southwestern and southern flank of the uplift is marked by the Terlingua Monocline. Cinnabar is the most common ore mineral localized along an east-west trend around Terlingua. It occurs as a replacement mineral and as a filling in rock openings such as fractures in igneous rocks. The most common deposits are along the contact between the Lower Cretaceous Devils River limestone and the Upper Cretaceous Grayson clay formation. The most valuable ore body occurred in the Chisos Pipe in the Chisos Mine.[8]

The Chisos Mine is located in the town of Terlingua and produced most of the quicksilver in the area. Discovered in 1902, it operated until 1943, producing 100,00 flasks of quicksilver. Three shafts connected 23 miles of workings over 17 levels. The mine included a 20-ton Scott furnace and a 100-ton rotary furnace. Cinnabar was discovered near the No. 9 shaft in about 1897, the basis for the preceding McKinney-Parker Mine. Peak production of 7,200 flasks occurred in 1917. The mine was operated by Howard E. Perry's Chisos Mining Co. until 1 Oct. 1942, when the company declared insolvency and was purchased by the Esperado Mining Co.[8] The Esperado Mining Co. closed the mine at the end of World War II. The village was abandoned and all company surface property was scrapped. At its peak, the mine employed 125 men around the clock.[3]:84,279,294

The second most prolific mine in the areas was the Mariposa Mine located 7 miles west of Terlingua. In 1901 the mine was operated by the Marfa and Mariposa Mining Co., owned by Montroyd Shayse and Thomas Golby. That company operated until 1910 when the mine was owned by the Esperado Mining Co. The mine produced between 20,000 and 30,000 flasks of quicksilver, most of it from 1895 to 1911, though production continued through World War II. Most of the production occurred on California Hill in cave-fill zones, which are solution caverns in the Devils River limestone. Calomel is most common.[3]:75[8]

The third largest producer of quicksilver in the area was the Study Butte Mine located 5 miles east of Terlingua. Cinnabar was discovered here in 1902 and mined since 1905. The property was operated in World War II by the Texas Mercury Co. Cinnabar occurs in ore bearing fractures or veins within a syenite intrusion. The mine included four principal shafts and two medium-sized furnaces.[8] The mine was soon abandoned when water was encountered, flooding the works.[3]:63

The district accounted for most of the US quicksilver production at least through 1937, almost 150,000 flasks. However, falling prices forced all of the mines to close by 1947.[8]

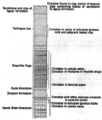

Geologic map of the Terlingua area

Geologic map of the Terlingua area Stratigraphic column indicating where cinnabar is found

Stratigraphic column indicating where cinnabar is found Terlingua's Robert Scott furnace (right) and eight condensers[3]:41,307–308

Terlingua's Robert Scott furnace (right) and eight condensers[3]:41,307–308

Culture

Due to its proximity to Big Bend National Park, today Terlingua is mostly a tourist destination for park visitors. Rafting and canoeing on the Rio Grande, mountain biking, camping, hiking, and motorcycling are some of the outdoor activities favored by tourists.

On the first Saturday of November, over 10,000 "chiliheads" convene in Terlingua for two annual chili cookoffs: the Chili Appreciation Society International] and the Frank X. Tolbert/Wick Fowler World Chili Championships. In the late 1970s, the Chili Cook-Off sponsored a “Mexican Fence-Climbing Contest” to spoof the U.S. government's planned reinforcement of the chain-link fence separating El Paso, Texas, from Cuidad Juárez, Mexico, and San Ysidro, California, from Tijuana, Mexico. The fence the “chili heads” used was constructed by undocumented Mexican workers who labored annually for the Cook-Off organizers at $5 a day plus meals and rustic lodging.[9] Among the founders of the first chili cookoff in 1967 was car manufacturer Carroll Shelby, who owned a 220,000-acre (890 km2) ranch nearby.[10]

Terlingua features in Wim Wenders' movie Paris, Texas. Travis is brought there to the German physician.

Terlingua was the focus of the 2015 National Geographic Channel show "Badlands, Texas."[11] The reality show followed the case surrounding the 2014 murder of Glenn Felts.[12][13][14]

Education

Education started with the 1909-1910 school year in a "tent-house". By 1923 the school consisted of 53 students taught in one adobe classroom. Four teachers had joined the staff by the 1927-1928 school year. In 1930 the Chisos Mining Company erected the Perry School. This was a four-room stucco building for the 141 students enrolled in the 1931-1932 school year.[3]:132–137

Terlingua is now served by the Terlingua Common School District, which serves Terlingua Elementary and Big Bend High.

Climate

This area has a large amount of sunshine year round due to its stable descending air and high pressure. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Terlingua has a mild desert climate, Bwh on climate maps.[15]

References

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Terlingua CDP, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Ragsdale, Kenneth (1976). Quicksilver, Terlingua and the Chisos Mining Company. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 14–21. ISBN 0890960135.

- ↑ Dumble, E.T. (1900). "Cretaceous and Later Rocks of Presidio and Brewster Counties", Transactions of the Texas Academy of Sciences for 1899, Together With The Proceedings From The Same Year. The Texas Academy of Sciences. Retrieved May 20, 2009. Describes c. 1894 and 1897 examinations in the area.

- ↑ American Mining Congress (1905). "Quicksilver Deposits of Terlingua District, Brewster County, Texas" Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Session of the American Mining Congress, El Paso, Texas, November 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18, 1905. pp. 184–194. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ↑ Hill, Benjamin Felix (1902). The University of Texas Mineral Survey, Bulletin No. 4, October, 1902: The Terlingua Quicksilver Deposits, Brewster County. Austin: The University of Texas. Retrieved May 20, 2009. Includes numerous c. 1902 photos of area mining operations.

- ↑ Photo (circa 1905) of the Terlingua Mining Company's furnace in Simonds, Frederic William (1905). The Geography of Texas. Boston: Ginn & Company. p. 104. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yates, Robert; Thompson, George (1959). Geology and Quicksilver Deposits in the Terlingua District Texas, USGS Professional Paper 312. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 1–114.

- ↑ Miller, Tom. On the Border: Portraits of America’s Southwestern Frontier, p. 102.

- ↑ Egan, Peter (September 2008). "Viva Terlingua!". Road & Track. 60 (1): 107–109.

- ↑ "Badlands, Texas". National Geographic Channel. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "¿Viva Terlingua? - Texas Monthly". Texas Monthly. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Terlingua Murder Trial Ends With 'Not Guilty' Verdict". www.newswest9.com. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ "Not guilty verdict in Terlingua 'ghost town' murder trial". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- ↑ Climate Summary for Terlingua, Texas

External links

- Kenneth B. Ragsdale, "Terlingua, Texas," Handbook of Texas Online, Published by the Texas State Historical Association, accessed December 23, 2012.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Terlingua, Texas

- Terlingua Green Scene, Community Garden and Farmers Market