Taoyuan County

| Taoyuan County 桃源县 | |

|---|---|

| County | |

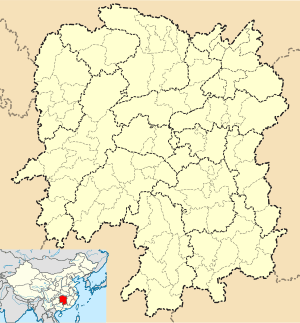

Taoyuan Location in Hunan | |

| Coordinates: 28°54′22″N 111°14′02″E / 28.906°N 111.234°ECoordinates: 28°54′22″N 111°14′02″E / 28.906°N 111.234°E[1] | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Hunan |

| Prefecture-level city | Changde |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,441 km2 (1,715 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,130 m (3,710 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 40 m (130 ft) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • Total | 976,000 |

| • Density | 220/km2 (570/sq mi) |

| Time zone | China Standard (UTC+8) |

| Postal code | 517000 |

| Area code | 0736 |

| Website |

taoyuan |

Taoyuan County (simplified Chinese: 桃源县; traditional Chinese: 桃源縣; pinyin: Táoyuán Xiàn) is under the administration of Changde, Hunan province, China. The Yuan River, a tributary of the Yangtze, flows through Taoyuan. It covers an area of 4441 square kilometers, of which 895 km2 (346 sq mi) is arable land. It is 229 km (142 mi) from Zhangjiang Town, the county seat, to Changsha, the capital city of Hunan province. The county occupies the southwestern corner of Changde City and borders the prefecture-level cities of Zhangjiajie to the northwest and Huaihua to the southwest.

History

The area of present-day Taoyuan County belonged to the Chu (state) during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period, and was a portion of Linyuan County during the Western Han Dynasty. In AD 50, the 26th year of Jianwu, the Eastern Han Dynasty was merged with Yuannan County, and administered by the Wuling Prefecture, separating it from Linyuan County. In AD 783, the third year of Sui Dynasty, Wuling County was created by annexing the three counties Linyuan, Yuannan, and Hanshou, administered by the Langzhou Prefecture.

In AD 963, the third year of the Song Dynasty, Taoyuan County was officially established by separating a part of Wuling County. It was named after its famous Taohuayuan, a park named after the fable “Peach Blossom Spring”.

Its capital, Zhanjiang, is situated on the northern bank of Yuanjiang river.

Economy

Agricultural products include: rice, wheat, edible oils, sesame seeds, peanuts, cotton, and tobacco. Manufactured products include: machinery, textiles, chemicals, wood products, and leather goods. Local mines extract gold, silver, iron ore, and diamonds.

Education

Taoyuan has 123,000 students enrolled in its elementary schools, middle schools and high schools. 99.99% of children of compulsory education age are enrolled in schools, and 93.2% of children with disabilities are enrolled in schools.

Approximately 2000 high school graduates are admitted to colleges and universities each year.

Taoyuan Yizhong, the first Middle School of Taoyuan, which includes both a middle school and high school, is the most prestigious school in Taoyuan County.

Geography and climate

Geography

Taoyuan County is in the northwestern portion, 28°55′N 111°29′E / 28.917°N 111.483°E,[2] of Hunan Province. It is 118 km from its northernmost point, LaoPeng village, Reshi Town, to its southernmost point, Shizi Ling, Xuejiachong village, Xi'an Town and 75 km from its easternmost post, Caoxiezhou, Renfeng village, Mutangyuan Township, to its westernmost post, Wanjiahe, Gaofeng village, Niuchehe Township. Its total area is 4441.22 km2, which is the fourth largest in Hunan Province. 895 km2 (221,000 acres) is arable land, the largest area of arable land in Hunan Province.

The agricultural landscape consists of: 13.4% alluvial plains of the Yuanjiang River, 49.3% hillocks, and 36.0% hills and mountains.

Climate

Taoyuan County is a transition zone from subtropical to north subtropical having a humid subtropical climate with seasonal prevailing winds. All four seasons are distinct.

The average annual temperature is 16.5 Celsius. The average temperature is 4.5 degrees Celsius in January and 28.5 degrees Celsius in July.

The average annual precipitation is 147 centimeters (58 inches), gradually decreasing from south to north. The annual average relative humidity is 82%; the annual sunshine length is 1531 hours and frost-free period lasts 284 days.

Demographics

Taoyuan County has a population of 976,000 composed of a dominant Han ethnic group and twelve other minority ethnic groups of: Hui, Uyghur, Tujia, Man, Dong, Zhuang and Yao. The Uyghur and Hui number more than 3000 people.

Taoyuan Uyghurs

Around 5,000 Uyghurs live around Taoyuan County and other parts of Changde.[3][4][5][6] They are descended from a Uyghur leader Hala Bashi, from Turpan (Kingdom of Qocho), who the Ming dynasty Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang sent to Hunan in the 14th century (mid-1300s).[7][8][9] Along with him came Uyghur soldiers from which the Hunan Uyghurs descend. During the 1982 census 4,000 Uyghurs were recorded in Hunan.[10] They have genealogies from the period beginning 600 years ago to the present day. Keeping genealogical records is a Han Chinese custom which the Hunan Uyghurs adopted. These Uyghurs were given the surname Jian by the Emperor; they received a Chinese education.[11] A prominent Hunan Uyghur was Jian Bozan (1898–1968) who was a member of the Chinese Communist Party.[12] There is some confusion as to whether they practice Islam or not. Some scholars state that they have assimilated with the Han and do not practice Islam anymore, and that only their genealogies indicate their Uyghur ancestry.[13] Chinese news sources report that they are Muslim.[7]

The Uyghur troops led by Hala were ordered by the Ming Emperor to crush Miao rebellions and were given titles by him. Jian (simplified Chinese: 简; traditional Chinese: 簡; pinyin: Jiǎn) is the predominant surname among the Uyghur in Changde, and Hunan. Hala Bashi was given the title "Grand General of South-Pacifying Post of the Nation" by the Emperor (镇国定南大将军; 鎮國定南大將軍; Zhènguó Dìngnán Dàjiàngjūn[14][15] Another group of Uyghur have the surname Sai. Hui and Uyghur have intermarried in the Hunan area, and the Hui were also used by the Ming Emperor to crush revolts.[16] The Hui are descendants of Arabs and Han Chinese who intermarried, and they share the Islamic religion with the Uyghur in Hunan.[17] It is reported that they now number around 10,000 people. The Uyghurs in Changde are not very religious, and eat pork.[18] Older Uygurs disapprove of this, especially elders at the mosques in Changde, and they seek to draw them back to Islamic customs.[19]

In addition to eating pork, the Uygurs of Changde Hunan practice other Han Chinese customs, like ancestor worship at graves. Some Uyghurs from Xinjiang visit the Hunan Uyghurs out of curiosity or interest.[20] Also, the Uyghurs of Hunan do not speak the Uyghur language, instead, they speak Chinese as their native language, and Arabic for religious reasons at the mosque.[16]

Language

The Taoyuan dialect was profoundly influenced by the northern dialect since the path used by government messengers,speaking the northern dialect, travelling to Yunnan and Guizhou from the Song to the Qing dynasty, passed through Taoyuan. It was also influenced by the dialects of central Jiangxi since substantial numbers of people from Jishui, Zhangshu, and Fengcheng of Jiangxi relocated to Taoyuan in succession from the Ming dynasty to the early Qing dynasty.

There are two types of accents in the Taoyuan dialect, one of which is called the native accent spoken in the central area of Taoyuan, including Zhangjiang Town, Zoushi Town, Qihe Town, Sanyanggang Town, and part of Jianshi Town; the other is called the periphery accent, spoken in the strip area bordering the other counties.

Taoyuan dialect is a fusion of the northern and Jiangxi dialects. Its accent is close to those of the Sichuan, Chongqing, and Hubei dialects. It is categorized as Southwestern Mandarin.

Culture

Taoyuan has its unique folk custom characteristics since it is located in the transition zone between the Han nationality and ethnics.

In cooking, Lei cha (pounded tea), is a "five flavors soup" made by smashing a mixture of tea leaves, ginger, corn, meng beans and salt into a powder; it is popular drink in Taohuanyuan area. According to legend, Lei cha protected soldiers from pestilence caused by their inability to acclimatize to the environment in Taoyuan during the Eastern Han period when General Ma Yuan fought southward to Taoyuan.

Taoyuan has unique local operas. Wuling Opera is a popular local opera performed by professionals. Musty Notes received the National Artist Award for its performance and script writing. Nuo opera drama, called a "living fossil", is still widespread. The town of Sangyanggang is known as the home of Nuo Opera.

The Three Bar Drum, Yugu Drum, and string instruments are very popular as well.

Notable residents

- Song Jiaoren (Apr 5, 1882 - Mar 22, 1913), a Chinese republican revolutionary, political leader and a founder of the Kuomintang.

- Liu Kan (1906 – Mar 03, 1948), posthumously awarded rank of General of the Republic of China Army in 1953, was born in Zhengaotian village, Taohuanyuan Town.

- Wang Qimei (王其梅; Wáng Qíméi, Dec 27, 1914—Aug 15, 1967), awarded rank of Major General of PLA in 1955, was born in Wangjiaping village, Sanyanggang Town.

- Jian Bozan (1898-Dec 18, 1968), a prominent Marxist historian, Vice President of Beijing University from 1952 to 1968, was born in Huiwei village, Fengshu Uyghur Autonomous Township.

Towns

- Zhangjiang

- Zoushi

- Sanyanggang

- Taohuayuan

- Lingjintan

Tourist attractions

The Taohuayuan Scenic Area is a park modelled after the Peach Blossom Spring fable, (Chinese: 桃花源), about a land secluded from the outside mortal world depicted as an idyllic shangri-la by Tao Yuanming, (365–427), an Eastern Jin Dynasty poet.

References

- ↑ Google (2014-07-02). "Taoyuan" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ stin Jon Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson (1992). Bones in the sand: the struggle to create Uighur nationalist ideologies in Xinjiang, China. Harvard University. p. 30. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Ingvar Svanberg (1988). The Altaic-speakers of China: numbers and distribution. Centre for Mult[i]ethnic Research, Uppsala University, Faculty of Arts. p. 7. ISBN 91-86624-20-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Kathryn M. Coughlin (2006). Muslim cultures today: a reference guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 220. ISBN 0-313-32386-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Li Jinhui (2001-08-02). "DNA Match Solves Ancient Mystery". china.org.cn.

- 1 2 "Ethnic Uygurs in Hunan Live in Harmony with Han Chinese". People's Daily. 29 December 2000.

- ↑ Shuai Cai (2010-12-30). "Harmony and happiness in mind the Uighurs living in Taoyuan County". Xinhua News Agency.

- ↑ Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson, Justin Jon Rudelson (1997). Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-231-10786-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Zhongguo cai zheng jing ji chu ban she (1988). New China's population. Macmillan. p. 197. ISBN 0-02-905471-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Yangbin Chen (2008). Muslim Uyghur students in a Chinese boarding school: social recapitalization as a response to ethnic integration. Lexington Books. p. 58. ISBN 0-7391-2112-X. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Daily report: People's Republic of China, Issue 34; Issues 36-41. Distributed by National Technical Information Service. 1979. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ David Westerlund, Ingvar Svanberg (1999). Islam outside the Arab world. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 197. ISBN 0-312-22691-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Zhonghua Minguo guo ji guan xi yan jiu suo (2000). Issues & studies, Volume 36, Issues 1-3. Institute of International Relations, Republic of China. p. 184. Retrieved 26 Dec 2011.

According to a local account shared among township residents, Uygur ancestors were called by the emperor to the region to quell Miao rebels during the Ming Dynasty and accepted titles from the emperor who bestowed part of the land as their own. The title "Grand General of South-Pacifying Post of the Nation" S & fa also carries a given Han surname, Jian ( fij ), which currently makes the largest Uygur group in Changde. According to an expert on Changde Uygurs,6 while Jian is a

Original from the University of Michigan - ↑ 海峽交流基金會 (2000). 遠景季刊, Volume 1, Issues 1-4. 財團法人海峽交流基金會. p. 38. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- 1 2 Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 133. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 135. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 137. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 138. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 136. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

External links

- Taoyuan County profile (in English)

- Taoyuan County overview (in Chinese)

- Taoyuan County Government Website (in Chinese)