Tangent space

In mathematics, the tangent space of a manifold facilitates the generalization of vectors from affine spaces to general manifolds, since in the latter case one cannot simply subtract two points to obtain a vector that gives the displacement of the one point from the other.

Informal description

In differential geometry, one can attach to every point x of a differentiable manifold a tangent space, a real vector space that intuitively contains the possible "directions" at which one can tangentially pass through x. The elements of the tangent space are called tangent vectors at x. This is a generalization of the notion of a bound vector in a Euclidean space. All the tangent spaces of a connected manifold have the same dimension, equal to the dimension of the manifold.

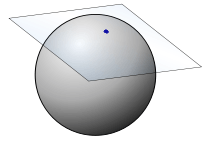

For example, if the given manifold is a 2-sphere, one can picture a tangent space at a point as the plane which touches the sphere at that point and is perpendicular to the sphere's radius through the point. More generally, if a given manifold is thought of as an embedded submanifold of Euclidean space one can picture a tangent space in this literal fashion. This was the traditional approach to defining parallel transport, and used by Dirac.[1] More strictly this defines an affine tangent space, distinct from the space of tangent vectors described by modern terminology.

In algebraic geometry, in contrast, there is an intrinsic definition of tangent space at a point P of a variety V, that gives a vector space of dimension at least that of V. The points P at which the dimension is exactly that of V are called the non-singular points; the others are singular points. For example, a curve that crosses itself doesn't have a unique tangent line at that point. The singular points of V are those where the 'test to be a manifold' fails. See Zariski tangent space.

Once tangent spaces have been introduced, one can define vector fields, which are abstractions of the velocity field of particles moving on a manifold. A vector field attaches to every point of the manifold a vector from the tangent space at that point, in a smooth manner. Such a vector field serves to define a generalized ordinary differential equation on a manifold: a solution to such a differential equation is a differentiable curve on the manifold whose derivative at any point is equal to the tangent vector attached to that point by the vector field.

All the tangent spaces can be "glued together" to form a new differentiable manifold of twice the dimension of the original manifold, called the tangent bundle of the manifold.

Formal definitions

The informal description above relies on a manifold being embedded in a larger vector space Rm, so that the tangent vectors can stick out of the manifold into the larger space. However, it is more convenient to define the notion of tangent space based on the manifold itself.[2] There are various equivalent ways of defining the tangent spaces of a manifold. While the definition via velocities of curves is intuitively the simplest, it is also the most cumbersome to work with. More elegant and abstract approaches are described below.

Definition as velocities of curves

In the embedded manifold picture, a tangent vector at a point x is thought of as the "velocity" of a curve passing through the point x. We can therefore take a tangent vector to be an equivalence class of curves passing through x while being tangent to each other at x.

Suppose M is a Ck manifold (k ≥ 1) and x is a point in M. Pick a chart φ : U → Rn where U is an open subset of M containing x. Suppose two curves γ1 : (-1,1) → M and γ2 : (-1,1) → M with γ1(0) = γ2(0) = x are given such that φ ∘ γ1 and φ ∘ γ2 are both differentiable at 0. Then γ1 and γ2 are called equivalent at 0 if the ordinary derivatives of φ ∘ γ1 and φ ∘ γ2 at 0 coincide. This defines an equivalence relation on such curves, and the equivalence classes are known as the tangent vectors of M at x. The equivalence class of the curve γ is written as γ'(0). The tangent space of M at x, denoted by TxM, is defined as the set of all tangent vectors; it does not depend on the choice of chart φ.

To define the vector space operations on TxM, we use a chart φ : U → Rn and define the map (dφ)x : TxM → Rn by (dφ)x(γ'(0)) = (φ ∘ γ)(0). It turns out that this map is bijective and can thus be used to transfer the vector space operations from Rn over to TxM, turning the latter into an n-dimensional real vector space. Again, one needs to check that this construction does not depend on the particular chart φ chosen, and in fact it does not.

Definition via derivations

Suppose M is a C∞ manifold. A real-valued function ƒ: M → R belongs to C∞(M) if ƒ ∘ φ−1 is infinitely differentiable for every chart φ : U → Rn. C∞(M) is a real associative algebra for the pointwise product and sum of functions and scalar multiplication.

Pick a point x in M. A derivation at x is a linear map D : C∞(M) → R that has the property that for all ƒ, g in C∞(M):

modeled on the product rule of calculus. If we define addition and scalar multiplication for such derivations by

and

we get a real vector space which we define as the tangent space TxM.

The relation between the tangent vectors defined earlier and derivations is as follows: if γ is a curve with tangent vector γ'(0), then the corresponding derivation is D(ƒ) = (ƒ ∘ γ)'(0) (where the derivative is taken in the ordinary sense, since ƒ ∘ γ is a function from (-1,1) to R).

- where .

Generalizations of this definition are possible, for instance to complex manifolds and algebraic varieties. However, instead of examining derivations D from the full algebra of functions, one must instead work at the level of germs of functions. The reason is that the structure sheaf may not be fine for such structures. For instance, let X be an algebraic variety with structure sheaf OX. Then the Zariski tangent space at a point p∈X is the collection of K-derivations D:OX,p→K, where K is the ground field and OX,p is the stalk of OX at p.

Definition via the cotangent space

Again we start with a C∞ manifold, M, and a point, x, in M. Consider the ideal, I, in C∞(M) consisting of all functions, ƒ, such that ƒ(x) = 0. That is, of functions defining curves, surfaces, etc. passing through x. Then I and I 2 are real vector spaces, and TxM may be defined as the dual space of the quotient space I / I 2. This latter quotient space is also known as the cotangent space of M at x.

While this definition is the most abstract, it is also the one most easily transferred to other settings, for instance to the varieties considered in algebraic geometry.

If D is a derivation at x, then D(ƒ) = 0 for every ƒ in I 2, and this means that D gives rise to a linear map I / I 2 → R. Conversely, if r : I / I 2 → R is a linear map, then D(ƒ) = r((ƒ - ƒ(x)) + I 2) is a derivation. This yields the correspondence between the tangent space defined via derivations and the tangent space defined via the cotangent space.

Properties

If M is an open subset of Rn, then M is a C∞ manifold in a natural manner (take the charts to be the identity maps), and the tangent spaces are all naturally identified with Rn.

Tangent vectors as directional derivatives

Another way to think about tangent vectors is as directional derivatives. Given a vector v in Rn one defines the directional derivative of a smooth map ƒ: Rn→R at a point x by

This map is naturally a derivation. Moreover, it turns out that every derivation of C∞(Rn) is of this form. So there is a one-to-one map between vectors (thought of as tangent vectors at a point) and derivations.

Since tangent vectors to a general manifold can be defined as derivations it is natural to think of them as directional derivatives. Specifically, if v is a tangent vector of M at a point x (thought of as a derivation) then define the directional derivative in the direction v by

where ƒ: M → R is an element of C∞(M). If we think of v as the direction of a curve, v = γ'(0), then we write

The derivative of a map

Every smooth (or differentiable) map φ : M → N between smooth (or differentiable) manifolds induces natural linear maps between the corresponding tangent spaces:

If the tangent space is defined via curves, the map is defined as

If instead the tangent space is defined via derivations, then

The linear map dφx is called variously the derivative, total derivative, differential, or pushforward of φ at x. It is frequently expressed using a variety of other notations:

In a sense, the derivative is the best linear approximation to φ near x. Note that when N = R, the map dφx : TxM→R coincides with the usual notion of the differential of the function φ. In local coordinates the derivative of ƒ is given by the Jacobian.

An important result regarding the derivative map is the following:

- Theorem. If φ : M → N is a local diffeomorphism at x in M then dφx : TxM → Tφ(x)N is a linear isomorphism. Conversely, if dφx is an isomorphism then there is an open neighborhood U of x such that φ maps U diffeomorphically onto its image.

This is a generalization of the inverse function theorem to maps between manifolds.

See also

References

- ↑ Dirac, 1975, General Theory of Relativity, Princeton University Press

- ↑ Chris J. Isham (1 January 2002). Modern Differential Geometry for Physicists. Allied Publishers. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-81-7764-316-9.

- Lee, Jeffrey M. (2009), Manifolds and Differential Geometry, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, Vol. 107, Providence: American Mathematical Society .

- Michor, Peter W. (2008), Topics in Differential Geometry, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, Vol. 93, Providence: American Mathematical Society .

- Spivak, Michael (1965), Calculus on Manifolds, HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-8053-9021-6

External links

- Tangent Planes at MathWorld