Sun Dance

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some indigenous people of United States of America and Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individuals make personal sacrifices on behalf of the community.

After European colonization of the Americas, and with the formation of the Canadian and United States governments, both countries passed laws intended to suppress Native cultures and encourage assimilation to majority-European culture. They banned Indigenous ceremonies and, in many schools and other areas, prohibited Indigenous people from speaking their native languages. In some cases they were not allowed to visit sacred sites when these had been excluded from the territory of reservations.

The Sun Dance was one of the prohibited ceremonies, as was the potlatch of the Pacific Northwest peoples.[1] Canada lifted its prohibition against practice of the full ceremony in 1951. But in the United States, Indigenous peoples were not allowed to openly practice the Sun Dance or other sacred ceremonies until the late 1970s, after they gained renewed sovereignty and civil rights following a period of high activism, including legal challenges to the government. Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) in 1978, which was enacted to protect basic civil liberties, and to protect and preserve the traditional religious rights and cultural practices of American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, and Native Hawaiians.[2]

Overview

Several features are common to the ceremonies held by sun dance cultures. These include dances and songs passed down through many generations, the use of a traditional drum, a sacred fire, praying with a ceremonial pipe, fasting from food and water before participating in the dance, and, in some cases, the ceremonial piercing of skin and a trial of physical endurance. Certain plants are picked and prepared for use during the ceremony.

Typically, the sun dance is a grueling ordeal for the dancers, a physical and spiritual test that they offer in sacrifice for their people. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, young men dance around a pole to which they are fastened by "rawhide thongs pegged through the skin of their chests."[3]

While not all sun dance ceremonies include piercing, the object of the sun dance is to offer personal sacrifice for the benefit of one's family and community. The dancers fast for many days, in the open air and whatever weather occurs.

At most ceremonies, family members and friends stay in the surrounding camp and pray in support of the dancers. Much time and energy by the entire community is needed to conduct the sun dance gatherings and ceremonies. Communities plan and organize for at least a year to prepare for the ceremony. Usually one leader or a small group of leaders are in charge of the ceremony, but many elders help out and advise. A group of helpers do many of the tasks required to prepare for the ceremony.

As this is a sacred ceremony, the people are reluctant to discuss it in any great detail. Given the harsh history with whites, they are rightly suspicious that non-Natives may abuse or misuse the traditional ways. Elders and medicine men are concerned that the ceremony should only be passed along in the right ways. The words used at a sun dance are often in the native language and are not translated for outsiders. Not talking about this ceremony is part of the respect the people display for it. In addition, the detailed way in which a respected elder speaks, teaches, and explains a sun dance to younger members of the tribe is unique and not easily quoted, nor is it intended for publication.

In 1993, responding to what they believed was frequent desecration of the sun dance and other Lakota sacred ceremonies, US and Canadian Lakota, Dakota and Nakota nations held "the Lakota Summit V." It was an international gathering of about 500 representatives from 40 different tribes and bands of the Lakota. They unanimously passed the following 'Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality':

"Whereas sacrilegious "sundances" for non-Indians are being conducted by charlatans and cult leaders who promote abominable and obscene imitations of our sacred Lakota sundance rites; ... We hereby and henceforth declare war against all persons who persist in exploiting, abusing, and misrepresenting the sacred traditions and spiritual practices of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota people." - Mesteth, Wilmer, et al (1993)[4][5]

In 2003, the 19th Generation Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe of the Lakota asked non-Native people to stop attending the sun dance (Wi-wanyang-wa-c'i-pi in Lakota); he stated that all can pray in support, but that only Native people should approach the altars.[6] This statement was supported by keepers of sacred bundles and traditional spiritual leaders from the Cheyenne, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota nations, who issued a proclamation that non-Natives would be banned from sacred altars and the Seven Sacred Rites, including and especially the sun dance, effective March 9, 2003 onward:

The Wi-wanyang-wa-c'i-pi (Sundance Ceremony): The only participants allowed in the center will be Native People. The non-Native people need to understand and respect our decision. If there have been any unfinished commitments to the sundance and non-Natives have concern for this decision; they must understand that we have been guided through prayer to reach this resolution. Our purpose for the sundance is for the survival of the future generations to come, first and foremost. If the non-Natives truly understand this purpose, they will also understand this decision and know that by their departure from this Ho-c'o-ka (our sacred altar) is their sincere contribution to the survival of our future generations.[6]

In Canada

Though only some Nations' sun dances include the body piercings, the Canadian Government outlawed that feature of the sun dance in 1895. It is unclear how often this law was actually enforced; in at least one instance, police are known to have given their permission for the ceremony to be conducted. The First Nations people simply conducted many ceremonies quietly and in secret. After gaining better understanding of and respect for Indigenous traditions, the government ended its prohibitions. Since 1951 Canada lifted its ban on the ceremony.[7] The sun dance is practiced annually on many reserves and reservations in Canada.

Although the Government of Canada, through the Department of Indian Affairs (now Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada), persecuted sun dance practitioners and attempted to suppress the dance, the ceremony itself was never officially prohibited. But Indian agents, based on directives from their superiors, did routinely interfere with, discourage, and disallow sun dances on many Canadian plains reserves from 1882 until the 1940s. Despite this, sun dance practitioners, such as the Plains Cree, Saulteaux, and Blackfoot, continued to hold sun dances throughout the persecution period. Some practiced the dance in secret, others with permissions from their agents, and others without the body piercing. The Cree and Saulteaux have conducted at least one Rain Dance (with similar elements) each year since 1880 somewhere on the Canadian Plains. In 1951, government officials revamped the Indian Act, dropping the prohibition against practices of flesh-sacrificing and gift-giving.[8]

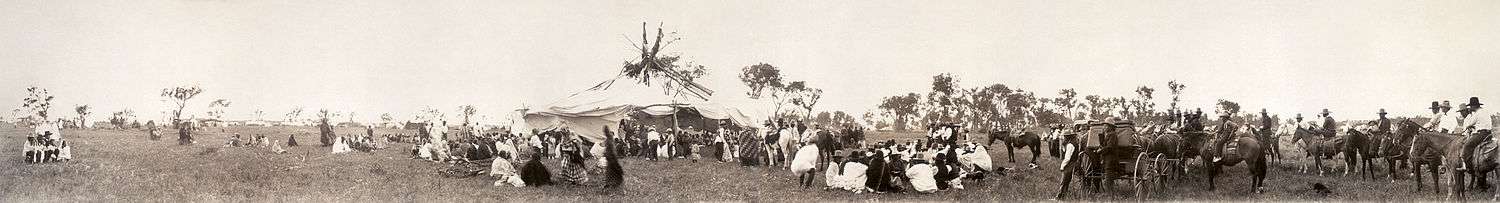

In most sun dance cultures, it is forbidden to film ceremony or prayer. Few images exist of authentic ceremonies. Many First Nations people believe that when money or cameras enter, the spirits leave, so no photo conveys an authentic ceremony. But the Kainai Nation in Alberta permitted filming of their sun dance in the late 1950s. This was released as the documentary Circle of the Sun (1960), produced by the National Film Board of Canada .[9][10] Manitoba archival photos show that the ceremonies have been consistently practiced since at least the early 1900s.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sun Dance. |

References

- ↑ Powell, Jay; & Jensen, Vickie. (1976). Quileute: An Introduction to the Indians of La Push. Seattle: University of Washington Press. (Cited in Bright 1984).

- ↑ Cornell.edu. "AIRFA act 1978.". Archived from the original on May 14, 2006. Retrieved July 29, 2006.

- ↑ Young, Gloria A. "Sun Dance." Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. The Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed 28 December 2013.

- ↑ Mesteth, Wilmer, et al (1993) "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality", The Peoples Path.

- ↑ Taliman, Valerie (1993) "The 'Lakota Declaration of War' ", News From Indian Country, Indian Country Communications, Inc.

- 1 2 Looking Horse, Chief Arvol (2003) "Protection of Ceremonies O-mini-c'i-ya-pi"

- ↑ "American Indian Religions Freedom". Native American Rights Fund. Justice Newsletter. Winter 1997.

- ↑ Brown, 1996: pp. 34-5; 1994 Mandelbaum, 1975, pp. 14-15; & Pettipas, 1994 p. 210. "A Description and Analysis of Sacrificial Stall Dancing: As Practiced by the Plains Cree and Saulteaux of the Pasqua Reserve, Saskatchewan, in their Contemporary Rain Dance Ceremonies" by Randall J. Brown, Master thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 1996. Mandelbaum, David G. (1979). The Plains Cree: An Ethnographic, Historical and Comparative Study. Canadian Plains Studies No. 9. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center. Pettipas, Katherine. (1994). Serving the Ties That Bind: Government Repression of Indigenous Religious Ceremonies on the Prairies. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Alan; John Corner. New Challenges for Documentary. Manchester University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-7190-6899-1.

- ↑ Low, Colin; Gil Cardinal. "Circle of the Sun". Curator's comments. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved 4 December 2009.