Art of Mesopotamia

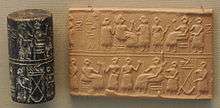

The art of Mesopotamia has survived in the archaeological record from early hunter-gatherer societies (10th millennium BC) on to the Bronze Age cultures of the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian empires. These empires were later replaced in the Iron Age by the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires. Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia brought significant cultural developments, including the oldest examples of writing. The art of Mesopotamia rivalled that of Ancient Egypt as the most grand, sophisticated and elaborate in western Eurasia from the 4th millennium BC until the Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered the region in the 6th century BC. The main emphasis was on various, very durable, forms of sculpture in stone and clay; little painting has survived, but what has suggests that, with some exceptions,[1] painting was mainly used for geometrical and plant-based decorative schemes, though most sculptures were also painted. Cylinder seals have survived in large numbers, many including complex and detailed scenes despite their small size.

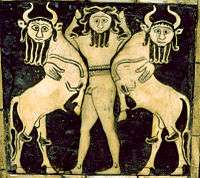

Mesopotamian art survives in a number of forms: cylinder seals, relatively small figures in the round, and reliefs of various sizes, including cheap plaques of moulded pottery for the home, some religious and some apparently not.[2] Favourite subjects include deities, alone or with worshippers, and animals in several types of scenes: repeated in rows, single, fighting each other or a human, confronted animals by themselves or flanking a human or god in the Master of Animals motif, or a Tree of Life.[3]

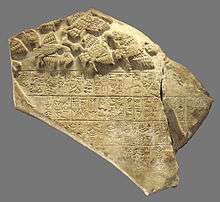

Stone stelae, votive offerings, or ones probably commemorating victories and showing feasts, are also found from temples, which unlike more official ones lack inscriptions that would explain them;[4] the fragmentary Stele of the Vultures is an early example of the inscribed type,[5] and the Assyrian Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III a large and well preserved late one.[6]

Uruk period

The Protoliterate or Uruk period, named after the city of Uruk in southern Mesopotamia, (ca. 4000 to 3100 BC) existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period, following the Ubaid period and succeeded by the Jemdet Nasr period generally dated to 3100–2900 BC.[7] It saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia, and the beginnings of Sumerian civilization,[8] and also the first "great creative age" of Mesopotamian art.[9] Slightly earlier, the northern city of Tell Brak, today in Syria, also saw urbanization, and the development of a temple with regional significance. This is called the Eye Temple after the many "eye idols", in fact votive offerings, found there, a type distinctive to this site. The stone Tell Brak Head, 7 inches high, shows a simplified face; similar heads are in gypsum. These were evidently fitted to bodies that have not survived, probably of wood.[10] Like temples further south, the Eye Temple was decorated with cone mosaics made up of clay cylinders some four inches long, differently coloured to create simple patterns.[11]

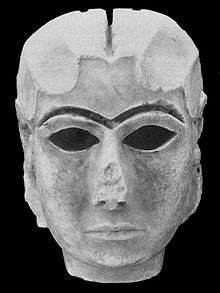

Significant works from the southern cities in Sumer proper are the Warka Vase and Uruk Trough, with complex multi-figured scenes of humans and animals, and the Mask of Warka. This is a more realistic head than the Tell Brak examples, like them made to top a wooden body; what survives of this is only the basic framework, to which coloured inlays, gold leaf hair, paint and jewellery were added.[12] The Guennol Lioness is an exceptionally powerful small figurine of a lion-headed monster,[13] perhaps from the start of the next period.

There are a number of stone or alabaster vessels carved in deep relief, and stone friezes of animals, both designed for temples, where the vessels held offerings. Cylinder seals are already complex and very finely executed and, as later, seem to have been an influence on larger works. Animals shown are often representations of the gods, another continuing feature of Mesopotamian art.[14] The end of the period, despite being a time of considerable economic expansion, saw a decline in the quality of art, perhaps as demand outstripped the supply of artists.[15]

-

Cast of the Warka Vase

-

The Mask of Warka

-

The Guennol Lioness, 3rd Millennium BC, 3.5 inches high

-

Limestone bull, Uruk c. 3000 BC

-

Cup with Nude Hero, Bulls and Lions, Tell Agrab, end of the period

-

pottery and cone mosaic pieces

Early Dynastic period

The Early Dynastic Period is generally dated to 2900–2350 BC. While continuing many earlier trends, its art is marked by an emphasis on figures of worshippers and priests making offerings, and social scenes of worship, war and court life. Copper becomes a significant medium for sculpture, probably despite most works having later being recycled for their metal.[16] Few if any copper sculptures are as large as the Tell al-`Ubaid Lintel, which is 2.59 metres wide and 1.07 metres high.[17]

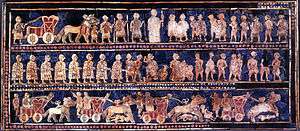

Many masterpieces have also been found at the Royal Cemetery at Ur (c. 2650 BC), including the two figures of a Ram in a Thicket, the Copper Bull and a bull's head on one of the Lyres of Ur.[18] The so-called Standard of Ur, actually an inlaid box or set of panels of uncertain function, is finely inlaid with partly figurative designs.[19]

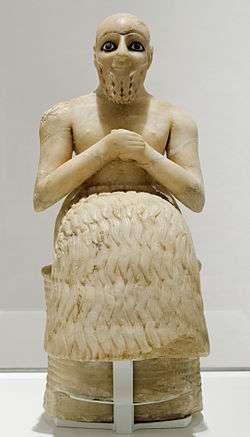

A group of 12 temple statues known as the Tell Asmar Hoard, now split up, show gods, priests and donor worshippers at different sizes, but all in the same highly simplified style. All have greatly enlarged inlaid eyes, but the tallest figure, the main cult image depicting the local god, has enormous eyes that give it a "fierce power".[20] Later in the period this geometric style was replaced by a strongly contrasting one giving "a detailed rendering of the physical peculiarities of the subject"; "Instead of sharply contrasting, clearly articulated masses, we see fluid transitions and infinitely modulated surfaces".[21]

-

"War"-panel of the Standard of Ur, ca. 2600 BC, showing parading men, animals and chariots

-

Bull's head from the Queen's Lyre from Pu-abi's grave, Ur,

-

Master of animals motif in a panel of the soundboard of the Ur harp

-

_(14580966009).jpg)

The Ur Queen's Lyre from Wooley's published record

-

Fragment of the Stele of the Vultures, Early Dynastic III period, 2600–2350 BC

-

Tell Asmar Hoard statue of worshipper, 2750-2600 BC

Akkadian period

The Akkadian Empire was the first to control not only all Mesopotamia, but other territories in the Levant, from about 2271 to 2154 BC. The Akkadians were not Sumerian, and spoke a Semitic language. In art there was a great emphasis on the kings of the dynasty, alongside much that continued earlier Sumerian art. In large works and small ones such as seals, the degree of realism was considerably increased,[22] but the seals show a "grim world of cruel conflict, of danger and uncertainty, a world in which man is subjected without appeal to the incomprehensible acts of distant and fearful divinities who he must serve but cannot love. This sombre mood ... remained characteristic of Mesopotamian art..."[23]

King Naram-Sin's famous Victory Stele depicts him as a god-king (symbolized by his horned helmet) climbing a mountain above his soldiers, and his enemies, the defeated Lullubi. Although the stele was broken off at the top when it was stolen and carried off by the Elamite forces of Shutruk-Nakhunte, it still strikingly reveals the pride, glory, and divinity of Naram-Sin. The stele seems to break from tradition by using successive diagonal tiers to communicate the story to viewers, however the more traditional horizontal frames are visible on smaller broken pieces. It is six feet and seven inches tall, and made from pink sandstone.[24][25] From the same reign, the bare legs and lower torso of the copper Bassetki Statue show an unprecedented level of realism, as does the imposing bronze head of a bearded ruler (Louvre).[26]

-

The Louvre head of one of the Akkadian kings

-

The copper Bassetki Statue

-

Detail of a victory stele

-

Seal impression

Between the Akkadians and Assyrians

The political history of this period of nearly 1300 years is complicated, including the Third Dynasty of Ur, the Isin-Larsa Period and First Babylonian Dynasty or Old Babylonian period, an interlude under the rule of the Kassites, and other periods. It ended with the decisive advent of the Neo-Assyrian Empire under Adad-nirari II, whose reign began in 911 BC. Life was often unstable, and non-Sumerian invasions a recurring theme. During the period Babylon became a great city, which was often the seat of the dominant power. The period was not one of great artistic development, these invaders failing to bring new artistic impetus,[27] and much religious art was rather self-consciously conservative, perhaps in a deliberate assertion of Sumerian values.[28] The quality of execution is often lower than in preceding and later periods.[29]

Gudea, ruler of Lagash (reign ca. 2144 to 2124 BC), was a great patron of new temples early in the period, and an unprecedented 26 statues of Gudea, mostly rather small, have survived from temples, beautifully executed, mostly in "costly and very hard diorite" stone. These exude a confident serenity.[30] The northern Royal Palace of Mari produced a number of important objects from before about 1800 BC, including the Statue of Iddi-Ilum,[31] and the most extensive remains of Mesopotamian palace frescos.[32]

The Burney Relief is an unusual, elaborate, and relatively large (20 x 15 inches) terracotta plaque of a naked winged goddess with the feet of a bird of prey, and attendant owls and lions. It comes from the 18th or 19th centuries BC, and may also be moulded. Similar pieces, small statues or reliefs of deities, were made for altars in homes or small wayside shrines, and small moulded terracotta ones were probably available as souvenirs from temples.[33]

This was generally not a period of the highest quality for cylinder seal images; at different times the inscription took prominence over the image, and the variety of scenes shown reduced, with the "presentation scene" of a king before a god, or an official before a seated king, becoming the norm at times.[34] Especially from the Kassite period several stone kudurru stelae survive, mostly taken up with inscriptions recording grants of land, boundary lines, and other official records, but often with figures and emblems of the gods or the king as well; a land grant by Meli-Shipak II is an example.[35]

Assyrian period

An Assyrian artistic style distinct from that of Babylonian art, which was the dominant contemporary art in Mesopotamia, began to emerge c. 1500 BC, well before their empire included Sumer, and lasted until the fall of Nineveh in 612 BC.

The conquest of the whole of Mesopotamia and much surrounding territory by the Neo-Assyrian Empire created a larger and wealthier state than the region had known before, and very grandiose art in palaces and public places, no doubt partly intended to match the splendour of the art of the neighbouring Egyptian empire. The Assyrians developed a style of extremely large schemes of very finely detailed narrative low reliefs in stone or alabster, and originally painted, for palaces. The precisely delineated reliefs concern royal affairs, chiefly hunting and war making. Predominance is given to animal forms, particularly horses and lions, which are magnificently represented in great detail. Human figures are comparatively rigid and static but are also minutely detailed, as in triumphal scenes of sieges, battles, and individual combat. Among the best known Assyrian reliefs are the lion-hunt alabaster carvings showing Assurnasirpal II (9th century BC) and the famous Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal (7th century BC), both of which are in the British Museum.[36] Reliefs were also carved into rock faces, as at Shikaft-e Gulgul, a style which the Persians continued.

The Assyrians produced very little sculpture in the round, except for colossal guardian figures, usually lions and winged beasts with bearded human heads, often the human-headed lamassu, which are sculpted in high relief on two sides of a rectangular block, with the heads effectively in the round (and also five legs, so that both views seem complete). These marked fortified royal gateways, an architectural form common throughout Asia Minor. Even before dominating the region they had continued the cylinder seal tradition with designs which are often exceptionally energetic and refined.[37] At Nimrud the carved Nimrud ivories and bronze bowls were found that are decorated in the Assyrian style but were produced in several parts of the Near East including many by Phoenician and Aramaean artisans.

The Assyrian form of the winged genie influenced Ancient Greek art, which in its "orientalizing period" added various winged mythological beasts including the Chimera, Griffin and winged horses (Pegasus) and men (Talos).[38]

Neo-Babylonian period

The famous Ishtar Gate, part of which is now reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, was the main entrance into Babylon, built in about 575 BC by Nebuchadnezzar II, the king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire who exiled the Jews; the empire lasted from 626 BC to 539 BC. The walls surrounding the entrance way are decorated with rows of large relief animals in glazed brick, which has therefore retained its colours. Lions, dragons and bulls are represented. The gate was part of a much larger scheme for a processional way into the city, from which there are sections in many other museums.[39] Large wooden gates throughout the period were strengthened and decorated with large horizontal metal bands, often decorated with reliefs, several of which have survived, such as the various Balawat Gates.

Other traditional types of art continued to be produced, and the Neo-Babylonians were very keen to stress their ancient heritage. Many sophisticated and finely carved seals survive. After Mesopotamia fell to the Persian Achaemenid Empire, which had much simpler artistic traditions, Mesopotamian art was, with Ancient Greek art, the main influence on the cosmopolitan Achaemenid style that emerged,[40] and many ancient elements were retained in the area even in the Hellenistic art that succeeded the conquest of the region by Alexander the Great.

Collections

By some margin, the most important collections are those of (in no particular order) the Louvre Museum, the British Museum and the National Museum of Iraq. The last was extensively looted after the breakdown of law and order following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, but the most important objects have largely been recovered. Several other museums have good collections, especially of the very numerous cylinder seals. Syrian museums have important collections from sites in modern Syria. The reconstructed Ishtar Gate in Berlin is arguably the most spectacular single work in a museum.

Gallery

| Ancient art history |

|---|

| Middle East |

| Asia |

| European prehistory |

| Classical art |

|

| History of art |

| Art history |

-

Stylized seated female figure with arms folded under her breasts, from Samarra, ca. 6000 BC

-

Old Babylonian cylinder seal, c. 1800: two kings and a goddess bring offerings to the sun god (at right). Linescan camera image reversed to resemble an impression.

-

Plaque showing a lion biting the neck of a man lying on his back, one of the Nimrud ivories, Neo-Assyrian period, 9th–7th centuries BC

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art of Mesopotamia. |

Notes

- ↑ Frankfort, 124-126

- ↑ Frankfort, Chapters 2–5

- ↑ Convenient summaries of the typical motifs of cylinder seals in the main periods are found throughout in Teissier

- ↑ Frankfort, 66–74

- ↑ Frankfort, 71–73

- ↑ Frankfort, 66–74; 167

- ↑ Crawford 2004, p. 69

- ↑ Crawford 2004, p. 75

- ↑ Frankfort, 27

- ↑ Frankfort, 241-242

- ↑ Frankfort, 24, 242

- ↑ Frankfort, 24-28, 31-32

- ↑ Frankfort, 32-33

- ↑ Frankfort, 28-37

- ↑ Frankfort, 36-39

- ↑ Frankfort, 55

- ↑ Frankfort, 60–61

- ↑ Frankfort, 61–66

- ↑ Frankfort, 71-76

- ↑ Frankfort, 46-49; the group are now divided between the Metropolitan Museum, New York, Oriental Institute, Chicago, and the National Museum of Iraq (with the god).

- ↑ Frankfort, 55-60, 55 quoted

- ↑ Frankfort, 83–91

- ↑ Frankfort, 91

- ↑ Kleiner, Fred (2005). Gardner's Art Through The Ages. Thomson-Wadsworth. p. 41. ISBN 0-534-64095-8.

- ↑ Frankfort, 86

- ↑ Frankfort, 91

- ↑ Frankfort, 127

- ↑ Frankfort, 93

- ↑ Frankfort, 110-116, 126

- ↑ Frankfort, 93 (quoted)-99

- ↑ Frankfort, 114–119

- ↑ Frankfort, 124-126

- ↑ Frankfort, 110–112

- ↑ Frankfort, 102-126

- ↑ Frankfort, 130

- ↑ Frankfort, 141–193

- ↑ Frankfort, 141–193

- ↑ Frankfort, 205

- ↑ Frankfort, 203–205

- ↑ Frankfort, 348-349

References

- Crawford, Harriet E. W. (16 Sep 2004). Sumer and the Sumerians (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521533386.

- Frankfort, Henri, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, Pelican History of Art, 4th ed 1970, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), ISBN 0140561072

- Teissier, Beatrice, Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals from the Marcopolic Collection, 1984, University of California Press, ISBN 0520049276, 9780520049277, google books

Further reading

- Crawford, Vaughn E.; et al. (1980). Assyrian reliefs and ivories in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: palace reliefs of Assurnasirpal II and ivory carvings from Nimrud. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870992600.

.jpg)