Striatum

| Striatum | |

|---|---|

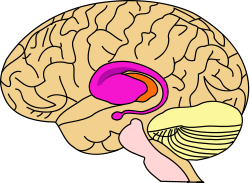

purple=caudate and putamen, orange=thalamus | |

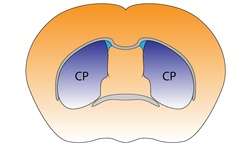

Caudoputamen of the mouse brain | |

| Details | |

| Part of |

Basal ganglia[1] Reward system[2][3] |

| Components |

Ventral striatum[2][3][4] Dorsal striatum[2][3][4] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | neostriatum |

| NeuroLex ID | Striatum |

| TA | A14.1.09.515 |

| FMA | 77616 |

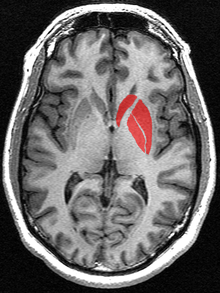

The striatum, also known as the neostriatum or striate nucleus, is a subcortical part of the forebrain and a critical component of the reward system. It receives glutamatergic and dopaminergic inputs from different sources and serves as the primary input to the rest of the basal ganglia system. In all primates, the dorsal striatum is divided by a white matter tract called the internal capsule into two sectors called the caudate nucleus and the putamen.[4] The ventral striatum is composed of the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle in primates.[4] Functionally, the striatum coordinates multiple aspects of cognition, including motor and action planning, decision-making, motivation, reinforcement, and reward perception.[2][3][4]

The corpus striatum, a macrostructure which contains the striatum, is composed of the entire striatum and the globus pallidus.[5] The lenticular nucleus refers to the putamen together with the globus pallidus.[6]

Structure

Cell types

The striatum is heterogeneous in terms of its component neurons.[7]

- Spiny projection neurons, commonly referred to as "medium spiny neurons", are the principal neurons of the striatum.[2] They are GABAergic and, thus, are classified as inhibitory neurons. Medium spiny projection neurons comprise 95% of the total neuronal population of the human striatum.[2] Medium spiny neurons have two primary phenotypes (i.e., characteristic types): D1-type MSNs of the "direct pathway" and D2-type MSNs of the "indirect pathway".[2][4][8] A subpopulation of MSNs contain both D1-type and D2-type receptors, with approximately 40% of striatal MSNs expressing both DRD1 and DRD2 mRNA.[2][4][8]

- Cholinergic interneurons release acetylcholine, which has a variety of important effects in the striatum. In humans, non-human primates, and rodents, these interneurons respond to salient environmental stimuli with stereotyped responses that are temporally aligned with the responses of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra.[9][10] The large aspiny cholinergic interneurons themselves are affected by dopamine through dopamine receptors D5.[11]

- There are many types of GABAergic interneurons.[7] The best known are parvalbumin expressing interneurons, also known as fast-spiking interneurons, which participate in powerful feed-forward inhibition of principal neurons.[12] Also, there are GABAergic interneurons that express tyrosine hydroxylase,[13] somatostatin, nitric oxide synthase and neuropeptide-Y. Recently, two types of neuropeptide-y expressing GABAergic interneurons have been described in detail,[14] one of which translates synchronous activity of cholinergic interneurons into inhibition of principal neurons.[15]

Adult humans continuously produce new neurons in the striatum, and these neurons could play a possible role in new treatments for neurodegenerative disorders.[16]

Anatomical subdivisions

The striatum is divided into ventral and dorsal subregions, based upon function and connectivity. The ventral striatum is composed of the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle, whereas the dorsal striatum is composed of the caudate nucleus and putamen.

The dorsal striatum can be differentiated based on immunochemical characteristics—in particular with regard to acetylcholinesterase and calbindin — into "compartments", consisting of "striosomes" and the surrounding "matrix" (See figure "Matrix and Striosome Compartments").

Inputs (afferent connections)

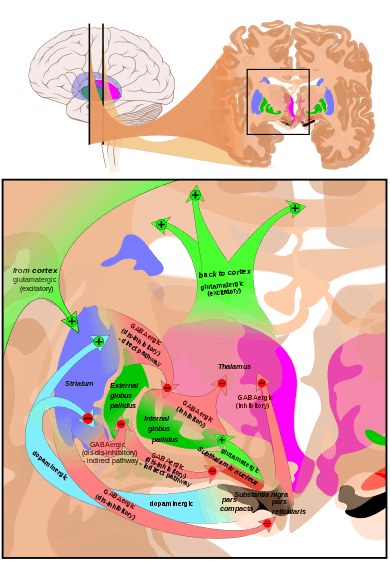

The most important afferent in terms of quantity of axons is the corticostriatal connection. Many parts of the neocortex innervate the dorsal striatum. The cortical pyramidal neurons projecting to the striatum are located in layers II-VI, but the most dense projections come from layer V.[18] They end mainly on the spines of the spiny neurons. They are glutamatergic, exciting striatal neurons. Another well-known afferent is the nigrostriatal connection arising from the neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta. While cortical axons synapse mainly on spine heads of spiny neurons, nigral axons synapse mainly on spine shafts. In primates, the thalamostriatal afferent comes from the central median-parafascicular complex of the thalamus (see primate basal ganglia system). This afferent is glutamatergic. The participation of truly intralaminar neurons is much more limited. The striatum also receives afferents from other elements of the basal ganglia such as the subthalamic nucleus (glutamatergic) or the external globus pallidus (GABAergic).

Targets (efferent connections)

Striatal outputs from both the dorsal and ventral components are primarily composed of medium spiny neurons (MSNs), a type of projection neuron, which have two primary phenotypes: "indirect" MSNs that express D2-type receptors and "direct" MSNs that express D1-type receptors.[2][4]

The basal ganglia core is made up of the striatum along with the regions to which it projects directly, via the striato-pallidonigral bundle. The striato-pallidonigral bundle is a very dense bundle of sparsely myelinated axons, giving a whitish appearance. This projection comprises successively the external globus pallidus (GPe), the internal globus pallidus (GPi), the pars compacta of the substantia nigra (SNc), and the pars reticulata of substantia nigra (SNr). The neurons of this projection are inhibited by GABAergic synapses from the dorsal striatum. Among these targets, the GPe does not send axons outside the system. Others send axons to the superior colliculus. Two others comprise the output to the thalamus, forming two separate channels: one through the internal segment of the globus pallidus to the ventral oralis nuclei of the thalamus and from there to the cortical supplementary motor area (SMA) and another through the substantia nigra to the ventral anterior nuclei of the thalamus and from there to the frontal cortex and the oculomotor cortex.

Function

The ventral striatum, and the nucleus accumbens in particular, primarily mediates reward cognition, reinforcement, and motivational salience, whereas the dorsal striatum primarily mediates cognition involving motor function, certain executive functions, and stimulus-response learning;[2][3][4][19] there is a small degree of overlap, as the dorsal striatum is also a component of the reward system that, along with the nucleus accumbens core, mediates the encoding of new motor programs associated with future reward acquisition (e.g., the conditioned motor response to a reward cue).[3][19]

Metabotropic dopamine receptors are present both on spiny neurons and on cortical axon terminals. Second messenger cascades triggered by activation of these dopamine receptors can modulate pre- and postsynaptic function, both in the short term and in the long term.[20][21] In humans, the striatum is activated by stimuli associated with reward, but also by aversive, novel,[22] unexpected, or intense stimuli, and cues associated with such events.[23] fMRI evidence suggests that the common property linking these stimuli, to which the striatum is reacting, is salience under the conditions of presentation.[24][25] A number of other brain areas and circuits are also related to reward, such as frontal areas. Functional maps of the striatum reveal interactions with widely distributed regions of the cerebral cortex important to a diverse range of functions.[26]

Clinical significance

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease results in loss of dopaminergic innervation to the dorsal striatum (and other basal ganglia) and a cascade of consequences. Atrophy of the striatum is also involved in Huntington's disease, choreas, choreoathetosis, and dyskinesias.[27]

Addiction

Addiction, a disorder of the brain's reward system, arises through the overexpression of ΔFosB, a transcription factor, in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the ventral striatum. ΔFosB is an inducible gene which is increasingly expressed in the nucleus accumbens following high doses of an addictive drug or overexposure to other addictive stimuli.[28][29]

Bipolar disorder

There is an association between striatal expression of the PDE10A gene and some bipolar disorder I patients.[30]

History

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the term "corpus striatum" was used to designate many distinct, deep, infracortical elements of the hemisphere.[31] In 1941, Cécile and Oskar Vogt simplified the nomenclature by proposing the term striatum for all elements built with striatal elements (see primate basal ganglia system): the caudate, the putamen, and the fundus striati, that ventral part linking the two preceding together ventrally to the inferior part of the internal capsule.

The term neostriatum was forged by comparative anatomists comparing the subcortical structures between vertebrates, because it was thought to be a phylogenetically newer section of the corpus striatum. The term is still used by some sources, including Medical Subject Headings.[32]

See also

References

- ↑ "Basal ganglia". BrainInfo. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Yager LM, Garcia AF, Wunsch AM, Ferguson SM (August 2015). "The ins and outs of the striatum: Role in drug addiction". Neuroscience. 301: 529–541. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.033. PMID 26116518.

[The striatum] receives dopaminergic inputs from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the substantia nigra (SNr) and glutamatergic inputs from several areas, including the cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus (Swanson, 1982; Phillipson and Griffiths, 1985; Finch, 1996; Groenewegen et al., 1999; Britt et al., 2012). These glutamatergic inputs make contact on the heads of dendritic spines of the striatal GABAergic medium spiny projection neurons (MSNs) whereas dopaminergic inputs synapse onto the spine neck, allowing for an important and complex interaction between these two inputs in modulation of MSN activity ... It should also be noted that there is a small population of neurons in the NAc that coexpress both D1 and D2 receptors, though this is largely restricted to the NAc shell (Bertran- Gonzalez et al., 2008). ... Neurons in the NAc core and NAc shell subdivisions also differ functionally. The NAc core is involved in the processing of conditioned stimuli whereas the NAc shell is more important in the processing of unconditioned stimuli; Classically, these two striatal MSN populations are thought to have opposing effects on basal ganglia output. Activation of the dMSNs causes a net excitation of the thalamus resulting in a positive cortical feedback loop; thereby acting as a ‘go’ signal to initiate behavior. Activation of the iMSNs, however, causes a net inhibition of thalamic activity resulting in a negative cortical feedback loop and therefore serves as a ‘brake’ to inhibit behavior ... there is also mounting evidence that iMSNs play a role in motivation and addiction (Lobo and Nestler, 2011; Grueter et al., 2013). ... Together these data suggest that iMSNs normally act to restrain drug-taking behavior and recruitment of these neurons may in fact be protective against the development of compulsive drug use.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Taylor SB, Lewis CR, Olive MF (February 2013). "The neurocircuitry of illicit psychostimulant addiction: acute and chronic effects in humans". Subst. Abuse Rehabil. 4: 29–43. doi:10.2147/SAR.S39684. PMC 3931688

. PMID 24648786.

. PMID 24648786. The DS (also referred to as the caudate-putamen in primates) is associated with transitions from goal-directed to habitual drug use, due in part to its role in stimulus–response learning.28,46 As described above, the initial rewarding and reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse are mediated by increases in extracellular DA in the NAc shell, and after continued drug use in the NAc core.47,48 After prolonged drug use, drug-associated cues produce increases in extracellular DA levels in the DS and not in the NAc.49 This lends to the notion that a shift in the relative engagement from the ventral to the dorsal striatum underlies the progression from initial, voluntary drug use to habitual and compulsive drug use.28 In addition to DA, recent evidence indicates that glutamatergic transmission in the DS is important for drug-induced adaptations and plasticity within the DS.50

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ferré S, Lluís C, Justinova Z, Quiroz C, Orru M, Navarro G, Canela EI, Franco R, Goldberg SR (June 2010). "Adenosine-cannabinoid receptor interactions. Implications for striatal function". Br. J. Pharmacol. 160 (3): 443–453. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00723.x. PMC 2931547

. PMID 20590556.

. PMID 20590556. Two classes of MSNs, which are homogeneously distributed in the striatum, can be differentiated by their output connectivity and their expression of dopamine and adenosine receptors and neuropeptides. In the dorsal striatum (mostly represented by the nucleus caudate-putamen), enkephalinergic MSNs connect the striatum with the globus pallidus (lateral globus pallidus) and express the peptide enkephalin and a high density of dopamine D2 and adenosine A2A receptors (they also express adenosine A1 receptors), while dynorphinergic MSNs connect the striatum with the substantia nigra (pars compacta and reticulata) and the entopeduncular nucleus (medial globus pallidus) and express the peptides dynorphin and substance P and dopamine D1 and adenosine A1 but not A2A receptors ... These two different phenotypes of MSN are also present in the ventral striatum (mostly represented by the nucleus accumbens and the olfactory tubercle). However, although they are phenotypically equal to their dorsal counterparts, they have some differences in terms of connectivity. First, not only enkephalinergic but also dynorphinergic MSNs project to the ventral counterpart of the lateral globus pallidus, the ventral pallidum, which, in fact, has characteristics of both the lateral and medial globus pallidus in its afferent and efferent connectivity. In addition to the ventral pallidum, the medial globus pallidus and the substantia nigra-VTA, the ventral striatum sends projections to the extended amygdala, the lateral hypothalamus and the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus. ... It is also important to mention that a small percentage of MSNs have a mixed phenotype and express both D1 and D2 receptors (Surmeier et al., 1996).

- ↑ "Corpus striatum". BrainInfo. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ↑ "DBS: The Basal Ganglia".

- 1 2 Tepper JM, Tecuapetla F, Koós T, Ibáñez-Sandoval O. Front Neuroanat. 2010 Dec 29;4:150. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2010.00150. PMID 21228905

- 1 2 Nishi A, Kuroiwa M, Shuto T (July 2011). "Mechanisms for the modulation of dopamine d(1) receptor signaling in striatal neurons". Front Neuroanat. 5: 43. doi:10.3389/fnana.2011.00043. PMC 3140648

. PMID 21811441.

. PMID 21811441. Dopamine plays critical roles in the regulation of psychomotor functions in the brain (Bromberg-Martin et al., 2010; Cools, 2011; Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011). The dopamine receptors are a superfamily of heptahelical G protein-coupled receptors, and are grouped into two categories, D1-like (D1, D5) and D2-like (D2, D3, D4) receptors, based on functional properties to stimulate adenylyl cyclase (AC) via Gs/olf and to inhibit AC via Gi/o, respectively ... It has been demonstrated that D1 receptors form the hetero-oligomer with D2 receptors, and that the D1–D2 receptor hetero-oligomer preferentially couples to Gq/PLC signaling (Rashid et al., 2007a,b). The expression of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors are largely segregated in direct and indirect pathway neurons in the dorsal striatum, respectively (Gerfen et al., 1990; Hersch et al., 1995; Heiman et al., 2008). However, some proportion of medium spiny neurons are known to expresses both D1 and D2 receptors (Hersch et al., 1995). Gene expression analysis using single cell RT-PCR technique estimated that 40% of medium spiny neurons express both D1 and D2 receptor mRNA (Surmeier et al., 1996).

- ↑ Goldberg, JA; Reynolds, JN (December 2011). "Spontaneous firing and evoked pauses in the tonically active cholinergic interneurons of the striatum.". Neuroscience. 198: 27–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.067. PMID 21925242.

- ↑ "Coincident but distinct messages of midbrain dopamine and striatal tonically active neurons.". Neuron. 43 (1): 133–43. July 2004. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.012. PMID 15233923.

- ↑ Bergson, C; Mrzljak, L; Smiley, J. F.; Pappy, M; Levenson, R; Goldman-Rakic, P. S. (1995). "Regional, cellular, and subcellular variations in the distribution of D1 and D5 dopamine receptors in primate brain". The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 15 (12): 7821–36. PMID 8613722.

- ↑ "Inhibitory control of neostriatal projection neurons by GABAergic interneurons.". Nat Neurosci. 2 (5): 467–72. May 1999. doi:10.1038/8138. PMID 10321252.

- ↑ Ibáñez-Sandoval, O; Tecuapetla, F; Unal, B; Shah, F; Koós, T; Tepper, JM (2010). "Electrophysiological and morphological characteristics and synaptic connectivity of tyrosine hydroxylase-expressing neurons in adult mouse striatum.". J Neurosci. 30 (20): 6999–7016. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5996-09.2010. PMID 20484642.

- ↑ Ibáñez-Sandoval, O; Tecuapetla, F; Unal, B; Shah, F; Koós, T; Tepper, JM (November 2011). "A novel functionally distinct subtype of striatal neuropeptide Y interneuron.". J Neurosci. 31 (46): 16757–69. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2628-11.2011. PMID 22090502.

- ↑ English DF, Ibanez-Sandoval O, Stark E, Tecuapetla F, Buzsáki G, Deisseroth K, Tepper JM, Koos T. Nat Neurosci. 2011 Dec 11;15(1):123-30. doi: 10.1038/nn.2984. PMID 22158514

- ↑ "Neuron-generating brain region could hold promise for neurodegenerative therapies". Science Daily. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ Reinius B; et al. (27 March 2015). "Conditional targeting of medium spiny neurons in the striatal matrix". Front. Behav. Neurosci.

- ↑ Rosell A, Giménez-Amaya JM (1999). "Anatomical re-evaluation of the corticostriatal projections to the caudate nucleus: a retrograde labeling study in the cat". Neurosci Res. 34 (4): 257–69. doi:10.1016/S0168-0102(99)00060-7. PMID 10576548.

- 1 2 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY, eds. Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 147–148, 367, 376. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

VTA DA neurons play a critical role in motivation, reward-related behavior (Chapter 15), attention, and multiple forms of memory. This organization of the DA system, wide projection from a limited number of cell bodies, permits coordinated responses to potent new rewards. Thus, acting in diverse terminal fields, dopamine confers motivational salience (“wanting”) on the reward itself or associated cues (nucleus accumbens shell region), updates the value placed on different goals in light of this new experience (orbital prefrontal cortex), helps consolidate multiple forms of memory (amygdala and hippocampus), and encodes new motor programs that will facilitate obtaining this reward in the future (nucleus accumbens core region and dorsal striatum). In this example, dopamine modulates the processing of sensorimotor information in diverse neural circuits to maximize the ability of the organism to obtain future rewards. ...

The brain reward circuitry that is targeted by addictive drugs normally mediates the pleasure and strengthening of behaviors associated with natural reinforcers, such as food, water, and sexual contact. Dopamine neurons in the VTA are activated by food and water, and dopamine release in the NAc is stimulated by the presence of natural reinforcers, such as food, water, or a sexual partner. ...

The NAc and VTA are central components of the circuitry underlying reward and memory of reward. As previously mentioned, the activity of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA appears to be linked to reward prediction. The NAc is involved in learning associated with reinforcement and the modulation of motoric responses to stimuli that satisfy internal homeostatic needs. The shell of the NAc appears to be particularly important to initial drug actions within reward circuitry; addictive drugs appear to have a greater effect on dopamine release in the shell than in the core of the NAc. - ↑ Greengard, P (2001). "The neurobiology of slow synaptic transmission". Science. 294 (5544): 1024–30. doi:10.1126/science.294.5544.1024. PMID 11691979.

- ↑ Cachope, R; Cheer (2014). "Local control of striatal dopamine release". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 8: 188. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00188. PMC 4033078

. PMID 24904339.

. PMID 24904339. - ↑ http://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/news-articles/0806/08062502

- ↑ Volman, S. F.; Lammel; Margolis; Kim; Richard; Roitman; Lobo (2013). "New insights into the specificity and plasticity of reward and aversion encoding in the mesolimbic system". Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (45): 17569–76. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3250-13.2013. PMC 3818538

. PMID 24198347.

. PMID 24198347. - ↑ LUNA, BEATRIZ; SWEENEY, JOHN A. (1 June 2004). "The Emergence of Collaborative Brain Function: fMRI Studies of the Development of Response Inhibition". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1021 (1): 296–309. doi:10.1196/annals.1308.035.

- ↑ "Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience: About the Department".

- ↑ Choi EY, Yeo BT, Buckner RL (2012). "The organization of the human striatum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity". Journal of Neurophysiology. 108 (8): 2242–2263. doi:10.1152/jn.00270.2012. PMID 22832566.

- ↑ Walker FO (January 2007). "Huntington's disease". Lancet. 369 (9557): 218–28. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. PMID 17240289.

- ↑ Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681

. PMID 24459410.

. PMID 24459410. - ↑ Olsen CM (Dec 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704

. PMID 21459101.

. PMID 21459101.

Table 1 - ↑ Science Daily: Scientists pinpoint gene variations linked to higher risk of bipolar disorder

- ↑ Raymond Vieussens, 1685

- ↑ Neostriatum at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Striatum. |

- Stained brain slice images which include the "striatum" at the BrainMaps project

- hier-207 at NeuroNames

- Corpus Striatum at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)