Lossiemouth

| Lossiemouth | |

| Scottish Gaelic: Inbhir Losaidh[1] | |

| Scots: Lossie[2] | |

|

|

Lossiemouth |

|

| Population | 6,803 |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | NJ235705 |

| Civil parish | Presbytery of Moray |

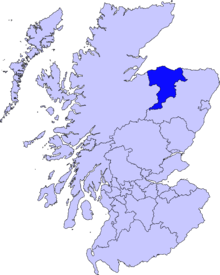

| Council area | Moray |

| Lieutenancy area | Moray |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LOSSIEMOUTH |

| Postcode district | IV31 6xx |

| Dialling code | 01343 |

| Police | Scottish |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| EU Parliament | Scotland |

| UK Parliament | Moray |

| Scottish Parliament | Moray |

| Website | www |

Coordinates: 57°43′08″N 3°17′15″W / 57.7189°N 03.2875°W

Lossiemouth (Scottish Gaelic: Inbhir Losaidh) is a town in Moray, Scotland. Originally the port belonging to Elgin, it became an important fishing town. Although there has been over a 1,000 years of settlement in the area, the present day town was formed over the past 250 years and consists of four separate communities that eventually merged into one. From 1890 - 1975 it was a police burgh as Lossiemouth and Branderburgh.

Stotfield, the first significant settlement (discounting Kinneddar which has now disappeared), lies to the north west of the town. Next was the Seatown - a small area between the river and the canal inholding of 52 houses, 51 of which are the historic fisher cottages. Following the decision to build a new harbour on the River Lossie, the 18th Century planned town of Lossiemouth, built on a grid system, was established on the low ground below the Coulard Hill. Branderburgh formed the final development during the 19th Century. This part of the town developed entirely as a result of the new harbour with its two basins and eventually covered the entire Coulard Hill and providing the town's impressive profile when seen from afar.

History

Roman to Medieval

Although the Romans never conquered the peoples of the North of Scotland, they made several journeys to the Moray Firth coast. Suspected Roman forts have been discovered at Thomshill, near Elgin and at Easter Galcantray, Cawdor, Nairnshire and also a suspected marching camp at Wester Alves, Moray.[3] The Greco-Roman astronomer and geographer, Claudius Ptolemaeus, generally known as Ptolemy (c. 90 – c. 168), describes in chapter 2 of his Geographa entitled Albion Island of Britannia the mouth of the River Lossie as ostium Loxa Fluvius. Settlement in this area has a long history. St Gervadius, a Celtic hermit inhabited a cave overlooking the entrance to the sea loch, Loch Spynie. In his time, the River Lossie entered the loch further to the south, near Inchbroom. The rocky promontory is recorded in the Chartulary of Moray as Holyman's Head and it is said that Gervadius (St Gerardine as he became known in later times) would walk around the headland with a flaming torch to warn ships away from the dangerous rocks. Even today the Halliman Skerries retain the reference to St Gervadius. He died in 934 AD and his cave became a place of pilgrimage right up to the 16th Century. The cave was eventually quarried out.

The settlement at the river mouth is significant particularly in its relationship with the Royal Burgh of Elgin. An argument between Alexander Bur, Bishop of Moray and John Dunbar, 4th Earl of Moray was documented in 1383 regarding the ‘ownership’ of the port of ‘Losey’. This document mentions that Losey was commonly known to fall within the limits of the episcopal estates. The Bishop’s description of the port suggests that it was well downstream from his fishing station at Spynie. It seems likely, therefore to look upon Losey as not merely a fishing station but as a trading port that the Elgin Burgesses used as a counterbalance to the Royal Burgh of Forres's trading port of Findhorn. The dispute with the Earl of Moray went further. That same year of 1383, the Earl wrote to the Elgin burgesses offering them the use of his port at the mouth of the River Spey with no duties in an attempt to take trade from the Bishop. The port and fishery was mentioned again in 1551.

The loch and the river became separated c.1600. A succession of storms built banks of sand and boulders that eventually closed off the sea entrance. To avoid flooding it is documented that, in 1609, the post-Reformation Protestant Bishop, Alexander Douglas took steps to exclude the River Lossie from the loch. Evidence of a sudden and unnatural looking right-angled bend between Caysbriggs and Inchbroom may indicate the location of this diversion.

Modern Lossiemouth has its origins in five separate communities that in time grew into one. These were Kinneddar, Stotfield, Seatown, Lossiemouth and finally, Branderburgh; the most ancient of these are Kinneddar and Stotfield.

Kinneddar

Kinneddar has now disappeared as a ferm toun, however an old farmhouse still retains its name and is probably its location. A Pictish settlement occupied the area and large numbers of carved stones, now held in Elgin Museum, were found. These stones date the settlement to around the 8th or 9th Century. Pictish crosses were found in or near the cemetery and indicate the presence of a Christian establishment. Early documented references to the settlement refer to it as Kenedor dating it to the 10th Century; it may, of course, have been a continuation of the original Pictish religious community. Saint Gervadius (Gerardine) is referred to as "Gervadius of Kenedor" and may have been part of this community, establishing his cell in the cave just to the northeast.

Bishop Richard is known to have resided at Kinneddar and for that period, it became the cathedral church of the diocese. However maps dating from the early 16th century clearly show this farming community as King Edward. National Library of Scotland It is unlikely, though, that this community took its name from King Edward I of England, The Hammer of the Scots, even though Edward travelled twice to this area to demonstrate his grip over the country; the most likely explanation is that the early cartographers took the local pronunciation of Kinneddar as King Edward and recorded it as such. He is known to have stayed in Elgin for four days in late July 1296 and it was during this sojourn into Scotland that he removed the Stone of Scone (Stone of Destiny) from Scone Palace and had it placed in a wooden chair at Westminster Abbey. He again stayed in Elgin for two days in September 1303 and then camped at Kinloss Abbey from the 13th of September till the 4th of October.

At that time the castle at Kinneddar, along with those at Elgin and Duffus, was left under the control of English garrisons. In 1308, Robert the Bruce, taking advantage of King Edward II's preoccupation with matters in England and France, started capturing and usually destroying castles that were either English garrisoned or controlled throughout Scotland. Joined by an army provided by David de Moravia, the Bishop of Moray, Bruce burned the castles of Inverness and Nairn before seizing and burning Kinneddar castle. He attacked Elgin castle only to be twice repulsed before finally succeeding. King Edward had the Bishop ex-communicated causing him to flee to Norway only to return after Edward's death.

Kinneddar village was still sizable in the early 19th century but dwindled away with the building of the new Lossiemouth, just to the east.

Stotfield

The early maps, some dating back to the early 16th century, clearly show Stotfield (some maps, name the settlement as Stotfold or Stodfauld). The name Stotfold means in Old English, 'horse fold'. The fact that the name is a form of English and not derived from Pictish or Gaelic names suggests that incomers settled the area. King David I introduced settlers from other parts of the kingdom as a way of reducing the powers of the lords who had ruled large territories as independent provinces. Indeed, King David put down a rebellion by the Mormaer of Moray in 1130 and it is possible that Stotfield dated from shortly after this event. The English-speaking inhabitants of the Lothians would most likely have been the chosen settlers. It is notable that the people inhabiting the Lothians were Angles (formally part of the Kingdom of Northumbria).

In the Middle Ages, Stotfield was primarily a farm hamlet with small scale fishing being carried out. The fishing gradually became more important and the population specialised into farm workers and fishermen. Subsistence was hard but at least it was relatively easy, in this case, for farm and sea food to be bartered. However, the religious strictures introduced following the Reformation impacted upon the community, especially the fishers.

The minutes from the Kinneddar Parish Kirk Session clearly show that the ancient superstitions were at least as important to them as observance of church niceties:

"17 Aprilis 1670 After Sermon the Session Assembling &c. The said day the fishers of Stotefold & Cousea being remitted from ye Presbetry to this Church discipline for satisfaction of yr (their) great & gross scandall & Idolatrous custome in burning torches on ye new years even The Presbetry having ordained y' (that) those psons mor in accession in this transgression yn (than) oyrs (others)satisfy ye discipline in Sacco And oyra (others) according to the arbitrement of ye Sessione. The Session do yrfore (therefore) ordain John Edward in Stotefold to satisfy in Sacco on day & to pay 20s[4] James Jafray in Cousea to satisfy in the Joges two dayes, Wm Innes Wm Hesbein Thomas Edward & John Thome all of ym (them) to testify yr(their) Repentance by standing at ye pillar And ilk ane of ym (them ) to pay 20s Alexr Innes owner of ye Boats of Stotefold, Wm Young owner of ye boats of Cousea each of ym (them) are ordained to pay 4 libs (pounds). In regard that they had not restrained this abuse Conform to yr (their) engagement before ye Presbetry in Ano 66 (year 1666) The fors (four) psons (persons) all of y snd Compeiring yr (their)sentence being intimated unto ym (them) they accepting & submitting to disciplin were sharpely rebuked exhorted to serious Repentance & enjoyned to satisfy conform to ye ordinance The next Lords day."

But the practices continued and, 35 years later, the minutes from the session records stated:

"23 Dec 1705 Also after sermon ye min1' (the minister) did guard ye Seamen to beware of ye old Heathenish superstitious practice of carrieing of lighted Clevies or torches about yr boats on new years even certifieing all that should be found any manner of way to concurr with or contribute to ye said work—should be put in ye hands of ye civill magistrate."

This is interesting because it shows that the power to fine parishioners had by then been removed and put in the hands of magistrates.

Parish records from Duffus Kirk show that similar experiences were happening at Brughsea (Burghead).[5] It is apparent, therefore, that Clavie burning was carried out in the three fisher towns of Brughsea, Causie (Covesea) and Stotefold (Stotfield). It is unlikely that this practice would have been restricted to the three Morayshire locations and that it would have been more widespread. Burghead still burns a ceremonial clavie on the eve of the old new year but is no longer associated with fishing boats. A puzzling date for the modern ceremony as the 17th Century ones were held on 31 December.

Stotfield fishing disaster

The Stotfield fishing disaster struck on Christmas Day 1806. The severity of this tragedy had an enormous effect upon the Stotfield community when every single able bodied male in the village perished in a huge storm. The folk memory of it is still retained among the fishermen of Lossiemouth.

Seatown

The Seatown was established at the end of the 17th Century when the old port at Spynie became landlocked. A succession of storms had built up large shingle banks to block the outlet of Loch Spynie to the sea. The merchants of Elgin decided that a new harbour that could berth larger trading vessels at the river mouth was required. The fishermen didn't use the new pier however but continued to sail their boats up to the beach at the Seatown. Seatown is called The Toonie by its inhabitants and sometimes referred to as the Dogwall. This was a reference to dogs-skins that were dried here before being turned into floats for nets.

Lossiemouth

In 1685, the Elgin burgh council called upon a German engineer, Peter Brauss, to look at the viability of providing a harbour at the mouth of the River Lossie; he decided that a harbour could be established. The first efforts at the beginning of the 18th Century looked to have failed but by 1764, the new jetty had been built at a cost of £1200.[6]

At the time that the new river mouth harbour was being constructed, so too was a more planned development laid out in streets running parallel and right angles to each other. An open square with a cross separated the first settlement from the new. The fishers occupied the houses at the Seatown and the builders, craftsmen and merchants in the new Lossiemouth. Later, a canal cut to drain Loch Spynie, would present a physical barrier to the two communities and entered the River Lossie in this area.

Branderburgh

By the early 19th century, the river harbour was busy but its long-term future was unsustainable and meant that a new solution was sought. In 1834, a Stotfield and Lossiemouth Harbour Company was formed to look into building a new harbour at Stotfield Point. That same year, The Inverness Courier carried the following:

"A paragraph is quoted from an Elgin paper under the heading "unexampled economy worthy of imitation." The two senior bailies of the burgh went on behalf of the town to Lossiemouth to meet the gentlemen appointed to stake off the ground for a proposed new harbour. The worthy Magistrates walked the whole distance, five miles out and five miles home, and only spent one shilling![7] This expenditure consisted of sixpence for whisky and the other sixpence to the waiter."

The construction of the new harbour was carried out between 1837 and 1839 but initially in a relatively small form. The beginning of the building process was marked by a ceremony and reported in the Inverness Courier as follows,

"The ceremony of laying the foundation stone of the inner basin of the new harbour at Stotfield Point, Lossiemouth, took place on the 15th inst [June]. The stone was laid by Lieut. Colonel James Brander of Pitgaveny, the proprietor of the site, with the assistance of the Trinity Lodge of Freemasons, and in presence of the Chairman and shareholders of the Harbour Company, and representatives of the burgh of Elgin."

This was the beginning of the final phase of building that was to become Branderburgh. However, by 1858, the basin had been enlarged further and deepened to 16 feet at spring tides. This encouraged many fishing families from up and down the coast to move to the town. The harbour as well as having a large herring fleet by now, also shared the available space with trading ships. This prompted the now renamed Elgin and Lossiemouth Harbour Company to build a new second basin at a cost of £18,000.[8] This basin was intended solely for fishing boats and opened in 1860.

Branderburgh, with its characteristic wide streets, continued to push its boundaries westward and by the early 20th century finally joined with Stotfield. A substantial amount of sandstone was quarried from the east side of the town to accommodate this rapid house building project. When Lossiemouth and Branderburgh became a police burgh in 1890, the town became mainly known as Lossiemouth, or more commonly – Lossie.

Fishing boats

The boats used at Stotfield, Seatown and finally Branderburgh were the same as those found across the entire Scottish east coast fishery. Chronologically, these were the two masted luggers, the Skaffies, Fifies and Zulus; then the powered Steam Drifters and Seine Netters.

- The Skaffie appeared at the beginning of the 19th Century. These boats were initially small so that they could be easily beached but later versions were heavier when large harbours became prevalent. Their stems were rounded and had raked sterns.

- The Fifie was the predominant fishing boat on the east coast from the 1850s until the mid-1880s. The Fifies main features were the vertical stem and stern. Fifies built from 1860 onwards were all decked and from the 1870s onwards the bigger boats were built with carvel planking, i.e. the planks were laid edge to edge instead of the overlapping clinker style of previous boats. Some boats were built up to about 70 feet in length and were very fast.

- The Zulu took its name from the Zulu war that was raging in South Africa at the time. Lossiemouth fisherman William 'Dad' Campbell was the first to introduce this form of fishing boat. His boat, the Nonesuch, had the characteristic vertical stem and steeply raking stern. The Zulu Boats rapidly became very popular in Lossiemouth and then along the whole of the east coast. Because these boats were ultimately very big and fast, they could reach the fishing grounds quickly and return with the catch equally fast.

- The Steam Drifters, so called because just like the Fifies and Zulus, they used drift nets. They were large boats, usually 80–90 feet in length with a beam of around 20 feet. Steam drifters had many advantages. They were usually about 20 ft (6 m) longer than the sailing vessels so they could carry more nets and catch more fish. This was important because the market was growing quickly at the beginning of the 20th century. They could travel faster and further and with greater freedom from weather, wind and tide. Because less time was spent travelling to and from the fishing grounds, more time could be spent fishing. However they did have disadvantages. They were expensive to build and run and as the herring fishery declined they became too expensive to operate.

- The Seine Netters initially were converted Fifies and Zulus. From 1906, petrol and paraffin engines began to be installed, initially for auxiliary power. However, as more powerful engines became available, sails (apart from the mizzen sail) were dispensed with. Danish seine net boats were landing huge quantities of plaice and other white fish at English east coast ports. Lossiemouth fishermen noted this and a few decided to use the seine net. It was obvious that this would be successful, but they were still hampered by the design and cost of the majority steam boats. John Campbell, nephew of William Campbell who designed the first Zulu boat, saw that a new design was needed to accommodate the large amounts of white fish that could be caught. His boat, the Marigold, did very well and over a short period the entire fleet (the first in Scotland) converted to the seine net.

Morayshire Railway

The Morayshire Railway was officially opened at ceremonies in Elgin and Branderburgh on 10 August 1852, the steam engines having been delivered to Lossie by sea. It was the first railway north of Aberdeen and initially travelled only the 5½ miles between Lossie and Elgin but later extended south to Craigellachie. The Lossie – Elgin section had three stops; the Rifle Range Halt, Greens of Drainie and Linksfield. The Great North of Scotland Railway took over the working of the line in 1863 and bought the company in 1881 following the Morayshire Railway's return from crippling debt back to solvency. The railway and harbour became very important to the economy of both Lossie and Moray. It was the Morayshire Railway that persuaded Col Brander, of Pitgaveny, to build the bridge from the Seatown to the east beach to encourage more day tripping in the summer months

Timeline

Geography, geology and wildlife

The town is locatedon the most northerly point of the south coast of the Moray Firth, at the mouth of the River Lossie. To the west of the town are a sandy beach, golf links and the Royal Air Force station, RAF Lossiemouth. Lossie Forest is a large pine forest that starts on the town's south-east boundary and the river splits it into two sections. The south side of the town is joined by the fertile plains of the Laich o' Moray.

Lossiemouth Beach is a large strip of dunes separated from the rest of the town by the River Lossie, creating a useful sheltered expanse of water. The town looks down onto this natural harbour with a plain promenade street from which there is a long wooden footbridge leading onto the sands. Ringed plover, grey heron, black-headed gull, oystercatcher, curlew, mallard and other waders feed under the bridge and are easy to watch from the street, and there are vast numbers of water birds in the more rural area further east.

A large part of the town is built on the Coulard Hill which consists of pale grey and yellow sandstones and with these is associated a cherty and calcareous band, known as 'the cherty rock of Stotfield' . This rock is a form of silica that contains micro-crystalline quartz. Also in the calcareous band of the Stotfield rock there is limestone with nodular masses of flint, crystals of galena (lead ore) and iron pyrites. The quarry on the east side of the town that produced the stone for the building of Branderburgh produced the largest variety and total numbers of fossil reptiles from the late Triassic Period to have been found in the UK. This was a total of eight species and 97 individuals; five of the species are unique to Lossiemouth, one of which is an early form of dinosaur. This quarry is ranked as one of Britain's most important fossil bearing locations of this period.

Climate

| Climate data for Lossiemouth | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6 (42) |

6 (43) |

8 (46) |

9 (49) |

13 (55) |

15 (59) |

17 (63) |

17 (63) |

15 (59) |

12 (53) |

8 (47) |

7 (44) |

11 (52) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1 (33) |

1 (33) |

2 (36) |

3 (38) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

11 (51) |

8 (47) |

6 (42) |

3 (37) |

2 (35) |

5 (41) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53 (2.1) |

48 (1.9) |

50 (2) |

46 (1.8) |

53 (2.1) |

56 (2.2) |

79 (3.1) |

84 (3.3) |

71 (2.8) |

80 (3) |

80 (3) |

64 (2.5) |

752 (29.6) |

| Source: Weatherbase[10] | |||||||||||||

Demography

| Population | Age structure (%) | Religion (%) | Country of birth (%) | Ethnic group (%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lossiemouth's population in 1901 was 3904

Economy

Lossiemouth is heavily dependent on the Royal Air Force station for its employment of civilians. In 2005, RAF Lossiemouth along with its neighbour RAF Kinloss contributed £156.5 million (including civilian expenditure) to the Moray economy, of which £76.6 million was retained and spent locally. The bases are responsible for providing, directly or indirectly, 21 per cent of all employment in the area.

Before the RAF, fishing was almost the sole industrialised process in Lossiemouth but now contributes very little to the overall economy; in 2001, fishing accounted for 1.62% (55 individuals) of the full-time employment of Lossiemouth. However, some engineering businesses once associated with fishing still exist in the town. Unlike other sizable towns in the area, Lossiemouth has not attracted the large supermarket groups due to its proximity to Elgin which also provides employment to a significant proportion of the working population.

Transport

Three roads converge on the town. The A941 connects to Elgin, while the B9103 joins the A96 (main Inverness to Aberdeen route) and the B9040 which connects to Hopeman and Burghead. There is a regular bus service to and from Elgin.

The nearest railway station is at Elgin and offers services every 90 to 120 minutes to both Inverness (circa 50 minutes travel time) and Aberdeen (circa 90 minutes travel time), which in turn provide services to the rest of the UK. The former Morayshire Railway line to Elgin was closed to passenger traffic in 1964 and goods in 1966. The former railway route has been turned into a footpath, and the edge of the station platform is visible in the main car park near the harbour.

There is a frequent bus service from Lossiemouth to Elgin.

Similarly, Inverness Airport (36 miles / 58 km) and Aberdeen Airport (62 miles / 101 km) offer a wide range of destinations.

Politics

National governments

- Lossiemouth is in the Moray (Westminster) constituency of the The United Kingdom Parliament which returns a Member of Parliament (MP) to the House of Commons,[13] at Westminster.

- Lossiemouth is in the Moray constituency of the The Scottish Parliament[14] which has slightly different boundaries to the UK Parliament constituency of the same name. The constituency returns a Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) to Holyrood and is part of the Highlands and Islands electoral region.

Local government

- Lossiemouth is part of The Moray Council[11] and elects its four representatives as part of the Heldon and Laich ward. As of May 3, 2007, these are John Hogg, Eric McGillivray, David Stewart and Allan Wright.

Education

Primary

- St Gerardine’s Primary School

- Hythehill Primary School

Secondary

- Lossiemouth High School is located in the south west of the town by the playing fields. Adjacent to the school is the swimming pool and community centre, which incorporates a playschool. Lossie High serves the Burghsea area, dominated by Lossiemouth itself and the villages Hopeman, Burghead, Cummingston and Duffus. The feeder primaries are Hythehill, St. Gerardine's, Hopeman and Burghead. There are over 700 pupils separated into four houses; Covesea, Kinnedar, Pitgaveny and Spynie.

Further

- Ecosse Performers College[15] is located at 56 High Street.

Religion

The following religious denominations have places of worship in Lossiemouth:

- St Gerardine's High, Drainie Parish Church, St Gerardines Road

- St James’ Church,[16] Prospect Terrace

United Free Church of Scotland

- United Free Church,[17] St Gerardines Road

- Lossiemouth Baptist Churchn[18] King Street

- Gospel Hall,[19] James Street

- St Margaret’s Church, Stotfield Road

- St Columba's Church, Union Street

Culture and leisure

- Lossiemouth Cruising Club[20] The Marina, Pitgaveny Quay

- Moray Golf Club, Stotfield Road. The club has two 18 hole courses.

- The Warehouse,[21] Pitgaveny Quay - Small intimate theatre/live music venue

- Lossiemouth Fisheries and Community Museum, Pitgaveny Quay

- Lossiemouth Folk Club

- Lossiemouth Bowling Club, St Gerardines Road

- Public Library, Town Hall Lane

- Swimming pool, adjacent to Lossiemouth High School

- Lossiemouth Youth Cafe (Mon, Wed, Fri, Sat)

Sport

The town's main football club is Lossiemouth F.C., nicknamed "The Coasters", who play in the Highland Football League. The club play their home games at Grant Park. They have won several trophies in recent seasons, including the Highland League Cup and several North of Scotland Cups. The local derby had been versus Elgin City FC, however their promotion to the higher Scottish leagues in recent years have reduced the frequency of the matches. The town's junior football club is Lossiemouth United. RAF Lossiemouth also has a junior football club. In addition, the station has a rugby union and a cricket club that play in their respective North of Scotland leagues and a rugby league side that plays in the Scotland Rugby League as the Moray Eels; most station teams also play in their respective RAF competitions. The Moray Golf Club is the town's golf club and has two courses, the Old Course established in 1889, designed by Old Tom Morris who predicted that it would become the best in the north,[22] and the 18 hole New Course, designed by Sir Henry Cotton, opened in 1979.

Language

The dialect of the Scots language spoken in Lossiemouth was closely related to the Doric dialect that was prevalent in Aberdeenshire. Many variations of this dialect can be heard along the Grampian coast, identifiable dialects from towns as close as 5 miles apart (i.e. Lossiemouth and Hopeman) is not unheard of. Just as the Doric is in decline, however, so it is in Lossiemouth. The reasons for this include the demise of Lossiemouth as a fishing port where its fishermen used Scots extensively. In fishing towns such as Peterhead and Fraserburgh, Scots is still widely spoken. In Lossiemouth, though, the high level of employment at the RAF station and a large population of non-Scots (nearly 25%) has hastened this decline. Quite a lot of the words still remain in use but on the whole, Scottish English is increasingly spoken among the indigenous population.

Twin town

Notable Lossie-ites

- James Ramsay MacDonald – first British Labour Prime Minister (1866–1937)

- Malcolm MacDonald – Labour MP, Minister, diplomat and author (1901–1981)

- Sergeant Alexander Edwards, VC – cooper and soldier (1885–1918)

- Gordon Campbell, Baron Campbell of Croy, MC PC DL – soldier, diplomat, Conservative MP, Cabinet Minister and Peer (1921–2005)

- Stewart Imlach – professional Footballer, Internationalist (1932–2001)

- Alan Main - Professional footballer and Scotland goalkeeper

- David West, RSW – Watercolour artist, gold prospector, sailor (1868–1936)

- Meg Farquhar – first female professional golfer in Britain (1910–1988)

- Jock Garden – Baptist minister, Australian politician and founder member of Australian Communist Party (1882–1968)

- George Fraser – leading hybridizer of rhododendrons in British Columbia, Canada

- Sir Alex Smith – former Head of Advanced Research, Rolls-Royce (1922 - 28 February 2003)

- Peter Kerr – Jazz musician, farmer, record producer and author

Gallery

Ocean Gleaner (returning after a refit)

Ocean Gleaner (returning after a refit) East Beach (from Prospect Terrace) - taken 1983

East Beach (from Prospect Terrace) - taken 1983 View of R. Lossie taken 2006 -note how dunes have grown in 23 years

View of R. Lossie taken 2006 -note how dunes have grown in 23 years Stotfield

Stotfield- East beach esplanade

Seatown and canal

Seatown and canal The golf course (two 18 hole courses)

The golf course (two 18 hole courses) Lossiemouth Harbour (East basin)

Lossiemouth Harbour (East basin)

Snippets

Two Royal Navy vessels, both named after the River Lossie, were involved in rescues following torpedo sinkings during the Second World War.

- HMS Lossie, a River class frigate, was patrolling in the Indian Ocean. On the 29 June 1944, the freighter Nellore was sunk and a week later HMS Lossie picked up 112 crewmen including the captain near the Chagos Archipelago and landed them at Addu Atoll.

- HMS River Lossie (requisitioned Aberdeen drifter A332) picked up the master and 41 crew members of the merchant ship Cairnmona off Rattray Head on 30 October 1939 after she was sunk by a German U-boat while in a convoy bound from Montreal to Leith and Newcastle.

Lossiemouth was mentioned in Yes, Prime Minister; character Bernard Woolley thought it was a type of dog food.

Footnotes

- ↑ "Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba ~ Gaelic Place-Names of Scotland". Gaelicplacenames.org. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ "Scots Language Centre: Scottish Place Names in Scots". Scotslanguage.com. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ Romans in Moray: Keillar, Ian

- ↑ 20 shillings (Scots) in 1670 was worth about £10 in 2005; £1 (English) = £12 (Scots)

- ↑ The letters "r" and "u" were transposed in later times but the local name for Burghead, ie the "Broch", can clearly be identified in the ancient spelling (Brughsea)

- ↑ £1200 in 1764 was worth about £125,000 in 2005

- ↑ One shilling in 1834 was worth about £3.70 in 2005; the whisky was cheap but that's a big tip to the waiter!

- ↑ £18,000 in 1860 was worth about £1.1 million in 2005

- ↑ Archived March 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Lossiemouth, Scotland". Weatherbase. 2011. Retrieved on November 24, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "moray.gov.uk". moray.gov.uk. 2013-12-18. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ "hie.co.uk". hie.co.uk. 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ Archived April 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/home.htm

- ↑ "ecosseperformers.co.uk". ecosseperformers.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ "stjameslossie.org.uk". stjameslossie.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ "Lossiemouth United Free Church of Scotland". Ufcos.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ "lossiebaptist.org". lossiebaptist.org. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ "lossiemouth.gospelhall.org.uk". lossiemouth.gospelhall.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ "lossiecc.co.uk". lossiecc.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ "thewarehousetheatre.co.uk". thewarehousetheatre.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ↑ McConachie, John: The Moray Golf Club, Elgin, 1988, p. 56

References

- Romans in Moray: Keillar, Ian ISBN

- Spynie Palace and the Bishops of Moray: Lewis, John H

- Archaeological Data Service

- The Permo-Triassic sandstones of Morayshire, Scotland: Ogilvie, Glennie and Hopkins

- SCRAN

- A Vision of Britain

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lossiemouth. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lossiemouth. |