Stocking frame

A stocking frame was a mechanical knitting machine used in the textiles industry. It was invented by William Lee of Calverton near Nottingham in 1589. Its use, known traditionally as framework knitting, was the first major stage in the mechanisation of the textile industry, and played an important part in the early history of the Industrial Revolution.

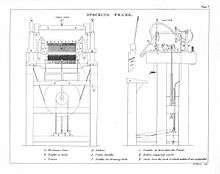

Description

Lee's machine consisted of a stout wooden frame. It did straight knitting not tubular knitting. It had a separate needle for each loop- these were low carbon steel bearded needles where the tips were reflexed and could be depressed onto a hollow closing the loop. The needle were supported on a needle bar that passed back and forth, to and from the operator. The beards were simultaneously depressed by a presser bar. The first machine had 8 needles per inch and was suitable for worsted: The next version had 16 needles per inch and was suitable for silk.[1]

- The mechanical movements

- The needle bar goes forward- the open needles clear the web

- The weft thread is lain on the needles

- The weft thread fall loosely

- The needle bar draws back, the weft is pulled in the open needles

- The needle bar draws back, the presser bar drops, the needle loops close and the weft is drawn back through tbe web

- The needles open, a new row has been added to the web which drops under gravity

History

The machine imitated the movements of hand knitters. Lee demonstrated the operation of the device to Queen Elizabeth I, hoping to obtain a patent, but Elizabeth refused, fearing the effects on hand-knitting industries. The original frame had 8 needles to the inch, which produced only coarse fabric. Lee later improved the mechanism with 20 needles to the inch. By 1598 he was able to knit stockings from silk, as well as wool, but was again refused a patent by James I. Lee moved to France with his workers and his machines, but was unable to sustain his business. He died in Paris c.1614. Most of his workers returned to England with their frames, which were sold in London.

The commercial failure of Lee's design might have led to a dead-end for the knitting machine, but John Ashton, one of Lee's assistants, made a crucial improvement by adding the mechanism known as a "divider".

Development

A thriving business built up with the exiled Huguenot silk-spinners who had settled in the village of Spitalfields just outside the city. In 1663, the London Company of Framework Knitters was granted a charter. By about 1785, however, demand was rising for cheaper stockings made of cotton. The frame was adapted but became too expensive for individuals to buy, thus wealthy men bought the machines and hired them out to the knitters, providing the materials and buying the finished product. With increasing competition, they ignored the standards set by the Chartered Company. Frames were introduced to Leicester by Nicholas Alsop in around 1680, who encountered resistance and at first worked secretly in a cellar in Northgate Street, taking his own sons and the children of near relatives as apprentices.[2] In 1728, the Nottingham magistrates refused to accept the authority of the London Company, and the centre of the trade moved northwards to Nottingham, which also had a lace making industry.

The breakthrough with cotton stockings, however, came in 1758 when Jedediah Strutt introduced an attachment for the frame which produced what became known as the "Derby Rib". The Nottingham frameworkers found themselves increasingly short of raw materials. Initially they used thread spun in India, but this was expensive and required doubling. Lancashire yarn was spun for fustian and varied in texture. They tried spinning cotton themselves but, being used to the long fibres of wool, experienced great difficulty. Meanwhile, the Gloucester spinners, who had been used to a much shorter wool, were able to handle cotton and their frameworkers were competing with the Nottingham producers.

Influence on the Industrial Revolution

It was then that Richard Arkwright arrived with his new experimental spinning machinery. He initially built a works operated by horsepower but it was evident that six to eight would be needed at a time, changed every half-hour. He moved to Cromford and set up what became known as the water frame. Strutt, as his partner, set up mills Belper and Milford. Thus the area joined Nottingham in producing cotton stockings, while Derby, with its mills originated by John Lombe continued largely with silk; Leicester, a farming area, continued with wool.

By 1812, there were estimated to be over 25,000 frames in use, most of them in the three counties, and the frame had come back to Calverton.

Postscript

A legend later developed that Lee had invented the first machine in order to get revenge on a lover who had preferred to concentrate on her knitting rather than attend to him. A painting illustrating this story was once displayed in the Stocking Framer's Guild hall in London. In 1846 the Victorian artist Alfred Elmore produced a variation on the story in his popular painting The Invention of the Stocking Loom, in which Lee is depicted pondering his idea as he watches his wife knitting (Nottingham Castle Museum).

See also

- Luddism

- Protection of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1788

- Destruction of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1812

- Water Frame

- Worshipful Company of Framework Knitters where it appears in their coat of arms

References

- Notes

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, pp. 12,13.

- ↑ John Gough Nichols, 'Notes on ancient hosiery', Leicester Architectural and Archaeological Society, Hinckley, July 1864; R.A. McKinley (Ed.), (Occupations: The hosiery industry), 'The City of Leicester: Social and administrative history, 1660-1835', A History of the County of Leicester, IV: The City of Leicester (1958), pp. 153-200; J. Thompson, The History of Leicester in the 18th Century (Leicester & London 1871), pp. 254-57.

- Bibliography

- Earnshaw, Pat (1986). Lace Machines and Machine Laces. Batsford. ISBN 0713446846.

- Cooper, B., (1983) Transformation of a Valley: The Derbyshire Derwent, Heinneman, republished 1991 Cromford: Scarthin Books

External links

- Ruddington Framework Knitters' Museum

- William Lee - The Triumphs and Trials of an Elizabethan Inventor

- Hosiery in Online Encyclopedia Originally appearing in Volume V13, Page 790 of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Wigston Framework Knitters Museum, Leicestershire

- Historic Highlights in Development of Hosiery-Knitting By Mildred Barnwell Andrews