Steine House

| Steine House | |

|---|---|

|

The building from the southeast | |

| Location | 55 Old Steine, Brighton, Brighton and Hove, East Sussex BN1 1NX, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 50°49′16″N 0°08′18″W / 50.8212°N 0.1384°WCoordinates: 50°49′16″N 0°08′18″W / 50.8212°N 0.1384°W |

| Built | 1804 |

| Built for | Maria Fitzherbert |

| Architect | William Porden |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name: Steine House and attached walls, piers and railings, 55 Old Steine | |

| Designated | 13 October 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1380672 |

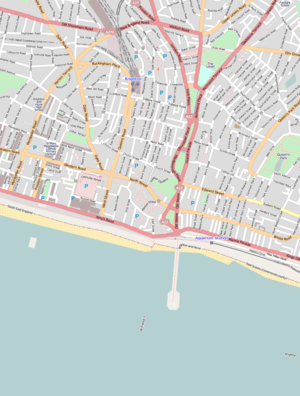

Location within central Brighton | |

Steine House is the former residence of Maria Fitzherbert, mistress and wife of the Prince Regent, in the centre of Brighton, part of the English city of Brighton and Hove. Designed in 1804 by William Porden, who was responsible for many buildings on the Prince's Royal Pavilion estate, it was used by Fitzherbert until her death 33 years later. Regular rebuilding has affected the appearance of the house since 1805, when it was damaged by a storm; more changes took place in 1884, when the YMCA bought it, and the building was "cruelly treated" by a refronting and extension in 1927. The YMCA continue to use the building, on Brighton's Old Steine next to Marlborough House, as a 65-person hostel. The extensive alterations have reduced its architectural importance, but the building has been listed at Grade II by English Heritage for its historical connections.

History

The Prince Regent (later King George IV) was one of the earliest and most important regular visitors to Brighton in its early years as a resort. It was transformed from a small fishing village after about 1750 when sea-bathing and drinking seawater became fashionable and popular, on the advice of influential local doctor Richard Russell.[1][2] The Prince's first visit to the town, in 1783 at the age of 21, lasted 11 days and attracted thousands of people eager to see both him and the sights which had attracted him.[3] The following year, he stayed for ten weeks of the summer to take the water cure. He visited again in 1785—the same year as he met and fell in love with Maria Fitzherbert, a widowed Roman Catholic. They married (illegally, against the provisions of the Royal Marriages Act 1772) in December 1785, and she first visited Brighton the following year.[4][5] At first, she stayed in a house whose site is believed to be near the present North Gate of the Royal Pavilion;[4][6] a terrace of nine houses, Marlborough Row, existed there until 1820, when all but one were demolished when the Royal Pavilion estate was redeveloped. (The surviving house, number 8, is now called North Gate House and stands alongside the North Gate.)[7] Even when the Royal Pavilion, the Prince's Brighton residence, was completed in 1787, the couple never stayed in the same house together. Under pressure to undertake a legal marriage to produce an heir, they divorced in 1794 and the Prince married Caroline of Brunswick; but they soon separated, and in June 1800 Mrs Fitzherbert and the Prince were reunited.[4][8]

The royal couple sought a site for a permanent home for Mrs Fitzherbert, and in 1804 she commissioned the Prince's favoured architect[9] William Porden to design and build a house on the west side of Old Steine, next to Marlborough House, to replace a Mr Tuppen's lodging house.[10] His design included a large colonnade across the front in an Egyptian style; this only lasted until the next year, when a storm destroyed it. He redesigned the façade in the Italianate style instead, with verandahs on both storeys.[9][11] Maria Fitzherbert lived at Steine House until her death on 27 March 1837, after which she was buried at St John the Baptist's Church, Brighton's oldest surviving Roman Catholic church.[8] Throughout her life in Brighton, she was treated extremely well by high society (statesman and writer John Wilson Croker remarked that "one reason why she may like this place is that she is treated as queen, at least of Brighton"),[8] and for the first few decades of the 19th century Steine House was the second most important house in Brighton after the Royal Pavilion.[10]

Steine House passed through several private owners after 1837, and finally passed out of residential use in the early 1860s when William Forder, a judge, sold it. At this time, a blocked staircase was discovered leading down from the cellar; false rumours abounded that a secret tunnel had been built between the house and the Royal Pavilion, and that the staircase led to this tunnel. It is considered more likely that the stairs gave access to Brighton's sewer network.[12] The building was converted into the Civil and United Services Club, a social club, which required major internal renovations;[9] these were completed in 1864.[13][14]

In 1884, the building was bought by the YMCA.[9][14] In 1927, they carried out a major reconstruction: the building was used as a hostel for vulnerable men, and more bedrooms were added;[9] the exterior was rebuilt, removing the verandahs and balconies;[15] and all remaining internal features except a staircase and a possibly original first-floor chapel were removed or altered.[14] An Earl of Barrymore once rode a horse up the cast-iron staircase, built to imitate bamboo, to win a bet.[9][10]

Steine House survived an attempt in 1964 to demolish it and replace it with offices, shops and a showroom. It is still owned by the YMCA, and functions as a 65-capacity short-term hostel.[9] In July 2009, the building was badly damaged by fire, and its residents had to be temporarily rehoused; it was soon restored.[16]

Steine House was listed at Grade II by English Heritage on 13 October 1952.[14] This status is given to "nationally important buildings of special interest".[17] As of February 2001, it was one of 1,124 Grade II-listed buildings and structures, and 1,218 listed buildings of all grades, in the city of Brighton and Hove.[18] The listing has been granted on the basis of the building's historical worth rather than its architectural quality, reflecting the negative effects of the frequent alterations.[9]

Architecture

The work done to Steine House in 1927, which drastically changed its appearance, has been universally condemned: historians have described the building as being "cruelly treated",[19] "sadly transformed"[20] and "disastrously refronted".[10] It now presents a façade of grey-painted brick with some stucco work. The roof is modern and in the mansard style. The building has two storeys and an extra half-storey above.[14]

The façade, facing east on to Old Steine, was partly set forward during the 1927 work, and dates solely from that time.[9] There are three straight-headed windows to the upper storey, and two flanking the entrance porch. The corners of the porch have pilasters topped with spheres. The ground-floor windows have small corbels underneath them and architraves above. The windows on the upper floor open out on to a balcony which is formed by the top of the projecting ground floor; this has four short piers with ironwork between them. The top floor is an attic with a single centrally placed dormer window.[14]

Inside, most[10] of Porden's intricately designed cast-iron staircase survives.[9][14] It has fretwork decoration and a balustrade, also made of cast iron, in the style of the staircases in the Royal Pavilion,[20] and was intended to look like bamboo.[10] Also partly surviving, but without its original walls, is Maria Fitzherbert's oval-shaped private chapel on the first floor.[10] No other original interior features are still in place.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 296.

- ↑ Musgrave 1981, pp. 46–48.

- ↑ Collis 2010, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 Collis 2010, p. 138.

- ↑ Musgrave 1981, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Musgrave 1981, p. 91.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 Collis 2010, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Collis 2010, p. 327.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dale 1950, p. 47.

- ↑ Dale & Gray 1976, p. 35.

- ↑ Dale 1950, pp. 47–48.

- 1 2 Brighton Polytechnic. School of Architecture and Interior Design 1987, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Historic England. "Steine House and attached walls, piers and railings, 55 Old Steine (west side), Brighton (Grade II) (1380672)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ Dale & Gray 1976, p. 36.

- ↑ "Brighton YMCA fire under investigation". The Argus. Newsquest Media Group. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ "Listed Buildings". English Heritage. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ "Images of England — Statistics by County (East Sussex)". Images of England. English Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ Antram & Morrice 2008, p. 85.

- 1 2 Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 447.

Bibliography

- Antram, Nicholas; Morrice, Richard (2008). Brighton and Hove. Pevsner Architectural Guides. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12661-7.

- Brighton Polytechnic. School of Architecture and Interior Design (1987). A Guide to the Buildings of Brighton. Macclesfield: McMillan Martin. ISBN 1-869865-03-0.

- Collis, Rose (2010). The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton. (based on the original by Tim Carder) (1st ed.). Brighton: Brighton & Hove Libraries. ISBN 978-0-9564664-0-2.

- Dale, Antony (1950). The History and Architecture of Brighton. Brighton: Bredin & Heginbothom Ltd.

- Dale, Antony; Gray, James S. (1976). Brighton Old and New. East Ardsley: EP Publishing. ISBN 0-7158-1188-6.

- Musgrave, Clifford (1981). Life in Brighton. Rochester: Rochester Press. ISBN 0-571-09285-3.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

_(IoE_Code_480996).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)