St John's College, Oxford

| Colleges and halls of the University of Oxford | ||||||||||||

| St John's College | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| College name | Saint John Baptist College | |||||||||||

| Latin name | Collegium Sancti Johannis Baptistae | |||||||||||

| Named after | Saint John the Baptist | |||||||||||

| Established | 1555 | |||||||||||

| Sister college | Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge | |||||||||||

| President | Margaret J. Snowling | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 385[1] (2016) | |||||||||||

| Graduates | 221[1] | |||||||||||

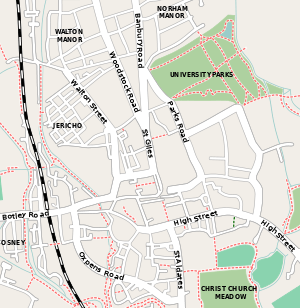

| Location | St Giles' | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Homepage | ||||||||||||

| Boatclub | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

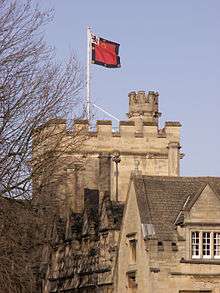

| Blazon | Gules, on a bordure sable, eight estoiles or, on a canton ermine, a lion rampant of the second, in chief an annulet of the third. | |||||||||||

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1555 by the merchant Sir Thomas White, intended to provide a source of educated Roman Catholic clerics to support the Counter-Reformation under Queen Mary. St John's is the wealthiest college in Oxford, with a financial endowment of £442.2 million as of 2015, largely due to nineteenth century suburban development of land in the city of Oxford, of which it is the ground landlord. [2]

The college occupies a central location on St Giles' and has a student body of approximately 390 undergraduates and 250 postgraduates.[3] As well as over 100 academic staff,[3] the college is supported by a similar number of other staff.[4]

History

On 1 May 1555, Sir Thomas White, lately Lord Mayor of London, obtained a Royal Patent of Foundation to create a charitable institution for the education of students within the University of Oxford. White, a Roman Catholic, originally intended St John's to provide a source of educated Roman Catholic clerics to support the Counter-Reformation under Queen Mary, and indeed Edmund Campion, the Roman Catholic martyr, studied here.

White acquired buildings on the east side of St Giles', north of Balliol and Trinity Colleges, which had belonged to the former College of St Bernard, a monastery and house of study of the Cistercian order that had been closed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Initially the new St John's College was rather small and not well endowed financially. During the reign of Elizabeth I the fellows lectured in rhetoric, Greek, and dialectic, but not directly in theology. However, St John's initially had a strong focus on the creation of a proficient and educated priesthood.[5]

White was Master of the Merchant Taylors' Company, and established a number of educational foundations, including the Merchant Taylors' School. Although the College was closely linked to such institutions for many centuries, it became a more open society in the later 19th century. (Closed scholarships for students from the Merchant Taylors' School, however, persisted until the late 20th century. As well as these, scholarships existed for students from Christ's Hospital, two for Coventry School, two for Bristol Grammar School, two for Reading School and one for Tonbridge School.[6]) Female students were first admitted in 1979, and Elizabeth Fallaize was appointed as the first female fellow in 1990.[7]

Although primarily a producer of Anglican clergymen in the earlier periods of its history, St John's also gained a reputation for both law and medicine.

Endowments

The endowments which St John's was given at its foundation, and during the twenty or so years afterward, served it very well and in the second half of the nineteenth century it benefited, as ground landlord, from the suburban development of the city of Oxford and was unusual among Colleges for the size and extent of its property within the city. The patronage of the parish of St Giles was included in the endowment of the college by Thomas White. Vicars of St Giles were formerly either Fellows of the College, or ex-Fellows who were granted the living on marriage (when Oxford fellows were required to be unmarried). The College retains the right to present candidates for the benefice to the bishop.[8] Today St John's maintains the largest endowment of the Oxford colleges, for example owning the Oxford Playhouse building[9] and the Millwall F.C. training ground.[10]

Buildings

The college is situated on a single 5.5 hectares (55,000 m2) site. Most of the college buildings are organised around seven quadrangles (quads).

Front Quadrangle

The Front Quadrangle mainly consists of buildings built for the Cistercian St Bernard's College. Construction started in 1437, though when the site passed to the crown in 1540, due to the Dissolution of the Monasteries, much of the exterior was as it is now, but the Eastern range was incomplete. Christ Church took control of the site in 1546 and Thomas White acquired it in 1554. The college founder made major alterations to create the current college hall, and designated the Northern part of the Eastern range to be the lodging of the President, for which it is still used today.[11] Front Quad was gravelled until the college's 400th anniversary when the current circular lawn and paving were laid out.[12]

The turret clock, made by John Knibb, dates from 1690.[13]

Chapel

The chapel was built and dedicated to St Bernard of Clairvaux in 1530.[14] The chapel was re-dedicated to St John the Baptist in 1557. The Baylie chapel in the north-east corner was added 1662-9 and refitted in 1949.[15] In 1840 the chapel's interior underwent major changes which created the gothic revival pews, roof, wall arcading and west screen.[14] Thomas White, William Laud and William Juxon are buried beneath the chapel. All three were presidents of the college, with the latter two also holding the role of Archbishop of Canterbury.[11] To the south of the chancel is a hidden pew directly accessible from the President's Lodgings, which historically allowed the only woman in college, the president's wife, to worship without distracting college members.[16]

Choral services have been sung in the chapel since 1618. Orlando Gibbons's famous anthem "This is the record of John" was written at the College's request, and presumably received its first performance here.[14] The college in 1620 commissioned the anthem As they departed from Michael East.[17] The college choir today sings evensong services on Sundays and Wednesdays during term time,[18] as well as singing the grace at Sunday formal hall. Since 1923 the choir has been directed by student organ scholars.[19] The chapel has always been home to an organ, and the present three keyboard instrument by Bernard Aubertin was installed in 2008.[20]

Canterbury Quadrangle

This quad is the first example of Italian Renaissance architecture in Oxford. It was substantially commissioned by Archbishop Laud and completed in 1636.[21]

The college library is here, consisting of three connected parts: The Old Library (south side, built 1596-8), The Laudian Library (built 1631–5 above the eastern colonnade, overlooking the garden) and The Paddy Room (1971-7).[22] Until moving to the Kendrew Quadrangle in 2010, the Holdsworth Law Library was situated in the neighbouring southwest corner of Canterbury Quadrangle. The college holds Robert Graves' Working Library[23] and in 1936 it acquired the 'A. E. Housman Classics Library', consisting of about 300 books and pamphlets containing hand-written notes by Housman in margins and on loose leaves.[24]

The Holmes Building is a 1794 south spur off the Canterbury Quad, containing fellows' rooms.[11]

North Quadrangle

The North Quadrangle was not designed as a whole, but is the irregular product of a series of buildings constructed since the college's foundation.

The college cook, Thomas Clarke, was given permission in 1612 to build a college kitchen, with residential rooms above. The college bought this building, just North of the hall, from Clarke in 1620 and expanded it during 1642-3 to produce the current Cook's Building.[11]

In 1676 the first part of today's Senior Common Room was constructed,[11] just North of the chapel. Its ceiling, completed in 1742, features the craftsmanship of Thomas Roberts, who also worked on the Radcliffe Camera and the Codrington Library.[25] Various additions and renovations took place in 1826, 1900, 1936[11] and 2004-5. The latest renovation and extension to the Grade I building was by MJP Architects and received two awards in 1996, the Design Partnership Award from the National Association of Shopfitters, and the other from the Royal Institute of British Architects .[26][27]

In 1742 property was bought from Exeter College, that between 1794 and 1880 was used for college purposes and known as the Wood Buildings. It was replaced when in 1880 the construction of today's St Giles' range began. What is today thought of as a single building was constructed as several distinct sections. The first part (1880–1) consisted of the gate tower and the rooms between it and Cook's building to the South. The second part to be constructed (1899–1900) forms the Northern half of the St Giles' range. Finally the Rawlinson Building (1909) formed the Northern side of the quadrangle. More rooms were added my Maufe in 1933.[11]

With the completion of the "Beehive" (1958–60), made up of non-regular hexagonal rooms, then the quadrangle took on its current appearance. Although looking like concrete, the Beehive is clad in Portland stone.[28] This Eastern part of the quadrangle previously hosted the old Fellow's Stables.[11]

Dolphin Quadrangle

The three houses 2-4 St Giles' formed an inn, named the Dolphin Inn. At the time of their demolition in 1881, the houses were known as the South Buildings, and were used as accommodation for the college.[29] In 1947-8 the college constructed on the site, at a cost of £43,216, the neo-Georgian Dolphin Quadrangle, designed by Edward Maufe.[30]

Sir Thomas White Quadrangle

Built in the 1970s, this is not actually a quadrangle, but an L-shaped building partially enclosing an area of garden. The upper floors are predominantly student residences, but ground floor contains communal facilities including the college bar, games room, TV room, DVD room and JCR. The Prestwich, Larkin and Graves rooms are multi-purpose and used for a variety of events.

The building is an early work by Ove Arup which has won both the 1976 Concrete Society Award,[31] and the 1981 Royal Institute of British Architects architectural excellence award.[32] It was also Commended in the 2011 Mature Building Category of the Construct: Concrete Awards.[33]

Garden Quadrangle

The Garden Quadrangle is a modern (1993) neo-Italianate design from MJP Architects that includes the college auditorium. The complex structure is very unlike a conventional quadrangle. As well as winning five awards (RIBA Award 1995, Civic Trust Award 1995, Oxford Preservation Trust Award 1994, Independent on Sunday Building of the Year 1994, Concrete Society Award – Overall Winner 1994) then a 2003 poll organised by The Oxford Times declared the £7.5m quadrangle to be the best building erected in Oxford in the preceding 75 years.[34][35]

The site was previously occupied by the Department of Agriculture, and the Parks Road frontage of this building survives today, separated from the quadrangle by a detached building containing three music rooms.[35]

Kendrew Quadrangle

The most recent quad, completed in 2010. The quad is named after Sir John Kendrew, former President of the College, Nobel Laureate and the College's greatest benefactor of the twentieth century. The construction has been dubbed "the last great quad in the city centre" and is notable for its attempt to provide energy from sustainable sources: much of the energy required to heat the building is provided by a combination of solar panels on the roof, geothermal pipes extending deep below the basement and woodchips from the College wood used to fire the boilers.

As the first phase of The Kendrew Quadrangle project Dunthorne Parker Architects were appointed by the College to refurbish three Grade II Listed buildings fronting on to St Giles. Works were carried out to No 20 St Giles which became alumni residential accommodation, The Black Hall, a 17th-century building, which became teaching accommodation and The Barn, which became an exhibition and performance space. This project was awarded an Oxford Preservation Trust Plaque in 2008.

Houses on Eastern side of St Giles'

The college now owns all the buildings on the Eastern stretch of St Giles'. Most of these are fairly unnoticeable, with various previous owners, today all used for various college purposes. However a few are more distinctive.

Middleton Hall is a curious house, north of the North Quad and abutting the Lamb and Flag.

Number 16 is St Giles' House, which dates from 1702. It was described by Nikolaus Pevsner as "the best house of its date in Oxford". It was previously known as The Judge's Lodgings, due to its use between 1852 and 1965 by the judge when visiting for Assizes.[36] It is today used by the college for dinners and receptions, with the upper levels including various rooms for tutors.

Western side of St Giles'

The college owns a stretch of the Western side of St Giles', including The Eagle and Child pub (where the well-known writers J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis often met their literary friends), complementing the Lamb and Flag opposite it on the College side of the road, which the College owns and operates (using the profits to fund graduate scholarships).

Gallery

Canterbury Quad

Canterbury Quad Gate from gardens

Gate from gardens Garden Party in the gardens

Garden Party in the gardens College gardens

College gardens 1986 drawing

1986 drawing

Student life

Facilities

St John's offers onsite accommodation to all undergraduates for the duration of their course (although students are not obliged to take up this offer). For first years, this is mostly in the Thomas White Quad, with some students accommodated in the Beehive. The College also accommodates some undergraduates (mostly second years) in houses owned by the college on Museum Road, with some postgraduates in Blackhall Road.

Middle Common Room

All graduate students are members of the Middle Common Room. The MCR represents graduates in the College, organises events and maintains graduate facilities.[37] The MCR building was completed in 1998.[38]

Societies

St John's College Boat Club (SJCBC) is the largest of a number of college sports clubs. In Summer Eights 2013, eight SJCBC boats qualified for the racing, and the women's 1st VIII bumped up to become the Head of the River - the first time any crew from SJCBC has achieved this in the club's 150-year history. The women's 1st Torpid won blades three years in succession from 2011 to 2013, and in 2013 also won the right to represent the Oxford colleges in the women's intercollegiate race at the Henley Boat Races.[39]

In 2006 St John's launched SJCtv, becoming the first Oxford college to start its own television station.[40] The college drama group operates under the banner of St John's Mummers. In addition to the chapel choir, the college regularly hosts performances from professional musicians and two non-auditioning ensembles (open to all Oxford students) rehearse in college: the Oxford Open Orchestra and Oxford University Symphonic Band.

St John's used to be the home of two dining societies, the King Charles Club and the Archery Club. Tony Blair has been pictured at a gathering of the latter in the St John's gardens.[41]

People associated with St John's

Fellows and alumni of St John's have included 17th century Archbishops of Canterbury William Laud and William Juxon, the early Fabian intellectual Sidney Ball, former Prime Minister of Canada Lester B. Pearson, former Sudanese prime minister Sadiq al-Mahdi, the poets A. E. Housman, Philip Larkin and Robert Graves, the novelist Kingsley Amis, the historian Peter Burke, the biochemist Sir John Kendrew, and former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Tony Blair.

John Smith, Chancellor of the Exchequer

John Smith, Chancellor of the Exchequer George Cave, 1st Viscount Cave, lawyer and Conservative politician

George Cave, 1st Viscount Cave, lawyer and Conservative politician William Laud, 76th Archbishop of Canterbury

William Laud, 76th Archbishop of Canterbury Tony Blair, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1997-2007)

Tony Blair, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1997-2007) Korn Chatikavanij, Thailand Finance Minister

Korn Chatikavanij, Thailand Finance Minister Alan Duncan, Conservative MP

Alan Duncan, Conservative MP.jpg) Geoff Gallop, 27th Premier of Western Australia

Geoff Gallop, 27th Premier of Western Australia David Heath, Liberal Democrat MP

David Heath, Liberal Democrat MP Abhisit Vejjajiva, 27th Prime Minister of Thailand (2008-2011)

Abhisit Vejjajiva, 27th Prime Minister of Thailand (2008-2011).jpg) Evan Davis, journalist and TV presenter

Evan Davis, journalist and TV presenter Yannis Philippakis, musician

Yannis Philippakis, musician

Presidents

The current President of St John's is Margaret J. Snowling, a British psychologist known for her work on dyslexia and recognised as a fellow of the British Academy.[42]

See also

- Fellows of St John's College, Oxford.

References

- 1 2 "Student Numbers 2011-12". University of Oxford.

- ↑ Saint John Baptist College in the University of Oxford (7 December 2015). "Annual Report and Financial Statements" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- 1 2 "About Us". St John's College Oxford. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ↑ St John's College, Oxford (31 October 2012). "Report and Financial Statements" (PDF). p. 21. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ Schmitt, Charles Bernard (1983) John Case and Aristotelianism in Renaissance England. Kingston [Ont.] : McGill-Queen's University Press ISBN 0-7735-1005-2

- ↑ The Student's Handbook to the University and Colleges of Oxford. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1891. p. 56.

- ↑ Still, Judith (2010-01-03). "Elizabeth Fallaize obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ↑ Kettler, Sarah Valente & Trimble, Carole (2003) The Amateur Historian's Guide to the Heart of England. Sterling, Va.: Capital Books 1892123657

- ↑ "Oxford Playhouse and University of Oxford". Oxford Playhouse. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

St John's College owns the Playhouse building, and leases the auditorium and adjoining offices to the Playhouse Trust.

- ↑ "Exclusive: Training ground purchase is on Millwall's agenda". News at Den Playhouse. 3 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

St. John's College, Oxford, bought the facility for £1.85million when Peter de Savary was chairman.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 H. E. Salter and Mary D. Lobel (editors) (1954). "St John's College". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3: The University of Oxford. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ Tyack, Geoffrey (2000). St John's College Oxford: A Short History and Guide. p. 21. ISBN 095389570X.

- ↑ Lisle, Nicola (17 December 2010). "The clockmakers of Claydon". The Oxford Times. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 "History". St John's College Oxford. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ Historic England. "St Johns College, North Range Including Chapel and Hall (1046649)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ↑ Tyack, Geoffrey (2000). St John's College Oxford: A Short History and Guide. p. 26. ISBN 095389570X.

- ↑ Peter Lynan, ‘East, Michael (c.1580–1648)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 24 December 2013

- ↑ "Choir". St John's College Oxford. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "Organ Scholars History". St John's College Oxford. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "Organ". St John's College Oxford. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ Mr Michael Riordan (24 June 2011). "St. John, the College and the Merchant Taylors' Company" (PDF). Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ "History". St John's College Oxford. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ "Robert Graves". St John's College Oxford. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ "A. E. Housman's Classics Library". St John's College Oxford. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ Tyack, Geoffrey (1998) Oxford: An Architectural Guide. Oxford University Press, 1998 ISBN 0-19-817423-3

- ↑ "Senior Common Room, St John's College". MJP Architects. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "Senior common room, St Johns College, Oxford". Royal Institute of British Architects. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ Historic England. "ST JOHNS COLLEGE, THE BEEHIVES (1278860)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ↑ Jenkins, Stephanie. "Dolphin Gate of Trinity College and Dolphin quadrangle of St John's". St Giles' Oxford. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Tyack, Geoffrey (28 April 2005). Modern Architecture in an Oxford College: St John's College 1945-2005. Oxford University Press. pp. 11–14. ISBN 9780199271627.

- ↑ The Times. 8 June 1976. p. 3. Missing or empty

|title=(help); - ↑ McKean, Charles (7 August 1981). "Double first for Arup designs". The Times. p. 3.

- ↑ "Sir Thomas White Building, St John's College". Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Little, Reg (2 February 2007). "St John's to build quad off St Giles". The Oxford Times. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Garden Quadrangle, St John's College". MJP Architects. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Jenkins, Stephanie. "No. 16: St Giles' House". St Giles' Oxford. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ St John's College MCR

- ↑ Tyack, Geoffrey (2000). St John's College Oxford: A Short History and Guide. p. 50. ISBN 095389570X.

- ↑ OURCs

- ↑ http://www.sjctv.co.uk

- ↑ "Blair in a boater, a crude hand gesture, and the Class of '75". Daily Mail. 3 March 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ "Professor Margaret J Snowling". British Academy. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St John's College, Oxford. |

- St John's College

- St John's College JCR

- Virtual Tour of St. John's College

- Works by or about St John's College, Oxford in libraries (WorldCat catalog)