Seyne

| Seyne | ||

|---|---|---|

|

A general view of the village of Seyne | ||

| ||

Seyne | ||

|

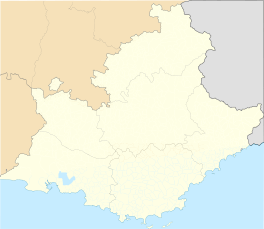

Location within Provence-A.-C.d'A. region  Seyne | ||

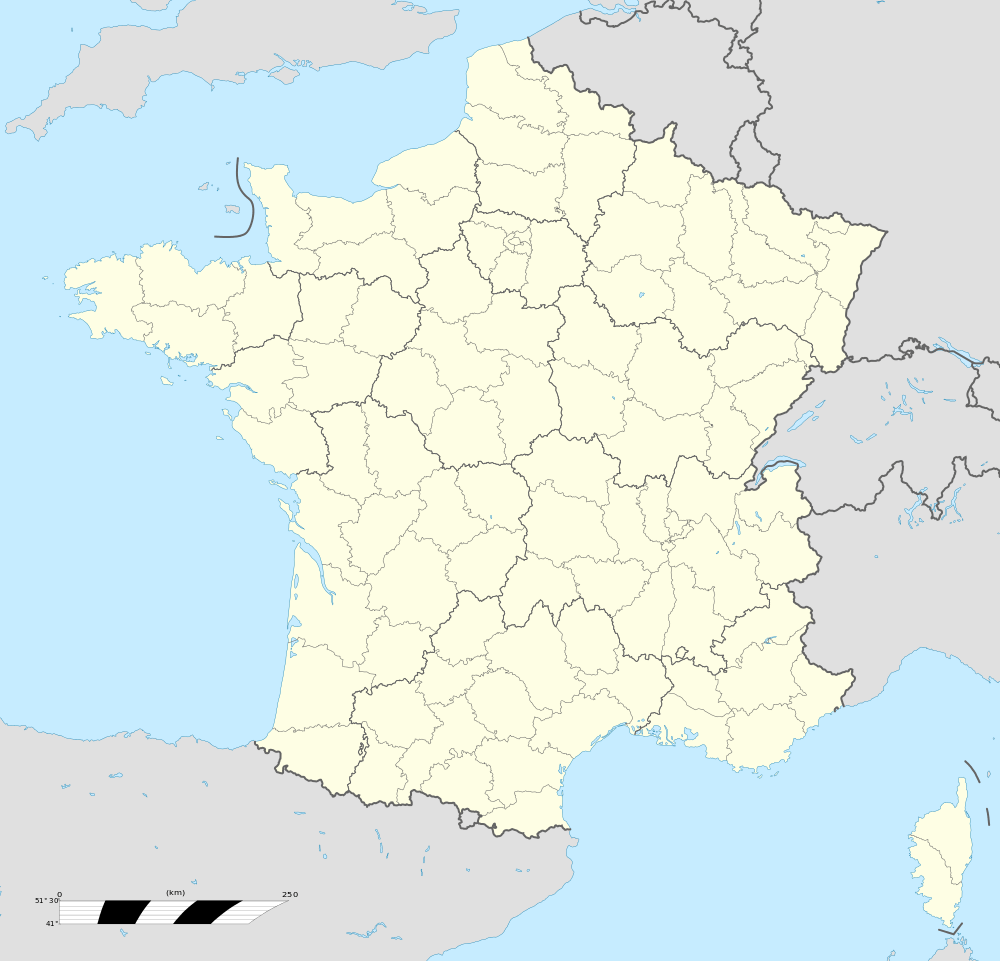

| Coordinates: 44°21′05″N 6°21′25″E / 44.3514°N 6.3569°ECoordinates: 44°21′05″N 6°21′25″E / 44.3514°N 6.3569°E | ||

| Country | France | |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | |

| Department | Alpes-de-Haute-Provence | |

| Arrondissement | Digne-les-Bains | |

| Canton | Seyne | |

| Intercommunality | Pays de Seyne | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor (2008–2014) | André Savornin | |

| Area1 | 84.27 km2 (32.54 sq mi) | |

| Population (2008)2 | 1,431 | |

| • Density | 17/km2 (44/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 04205 / 04140 | |

| Elevation |

1,079–2,720 m (3,540–8,924 ft) (avg. 1,260 m or 4,130 ft) | |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

Seyne is a commune in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department, and in the region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, in southeastern France. It is around 30 km north of Digne.

The official name of the municipality, as listed by the INSEE official geographic code, is Seyne. However, it is known at the local level as Seyne-les-Alpes, hitherto not endorsed by a decree. It is not to be confused with the town of La Seyne-sur-Mer which is the second town in the Var department.

The name of its inhabitants is Seynois.[1] More rarely today, it also uses Seynards and Seynardes locally.

Seyne has received the label of a village and town of character.

Geography

Geology and landforms

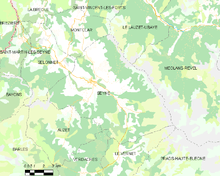

The village is situated at an altitude 1,260 metres (4,130 ft).[2] The valley bottoms with deep soil and cut hedges in the Seyne Valley are nicknamed the Swiss Provençal.[3]

Hydrography

It is crossed by the Blanche, a tributary of the Durance.[4]

Communication and transport

Seyne is accessible by the departmental road RD 900, between Le Lauzet-Ubaye in the north, and Digne in the south. The nearest SNCF railway station is the Gare de Digne.

Environment

The municipality has 2,800 hectares (6,900 acres) of woods and forests.[1]

Natural and technological hazards

None of the 200 communes of the Department is in the zero seismic risk zone. The Canton of Seyne is in zone 1b (low seismicity) determined by the 1991 classification, based on historical earthquakes,[5] and in zone 4 (medium risk) according to the probabilistic classification EC8 of 2011.[6] The commune of Seyne is also exposed to three other natural hazards:[6]

- Avalanche

- Wildfire

- Flood

- Landslide: some slopes of the municipality are covered by a medium to strong hazard.[7]

The commune of Seyne is more exposed to a risk of technological origin, that of transport of dangerous goods by road.[8] The departmental RD 900 (the former Route nationale 100) can allow for the road transport of dangerous goods.[9]

The predictable natural risk prevention plan (PPR) the commune was prescribed in 2006 for avalanche, flood, land movement and earthquake risk;[8] the DICRIM does not exist.[10]

The following list includes earthquakes felt strongly in Seyne. They exceeded a macro-seismic intensity level V on the MSK scale (sleepers awake, falling objects). The specified intensities are those felt in the town, the intensity can be stronger at the epicentre:[11]

- The earthquake of 22 March 1949 with intensity level V, and an epicentre located in the commune of Lauzet.[12]

- The earthquake of 20 March 1983 with an intensity level V, and an epicentre located in the commune of Seyne.[13]

Toponymy

The name of the village, as it appears the first time in 1147 (in Sedena), would refer to the Gallic tribe of the Édenates, or would be built on the root *Sed-, for rock, according to Charles Rostaing.[14] According to the Fénie couple, the name comes from a Pre-Celtic root oronym (mountain toponym), *Sed-.[15] The municipality is named Sanha in Vivaro-Alpine and Provençal of the classical norm, and Sagno in the Mistralian norm.

History

Antiquity

Before the Roman conquest, Seyne was the capital of the Édénates.[16] It received the status of civitas, under the Roman Empire.

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, it appeared in charters in 1146 (in Sedena)[17] When Ramon Berenguer IV of Barcelona forced the submission of the Provençal baronial who revolted (Baussenque Wars). After taking control of Arles, he summoned the Lords of Haute-Provence to Seyne where they renewed their tribute.[18] The lords were the Counts of Provence, who endowed the consulate as early as 1223[19] (1220 according to André Gouron),[20] which served as a model to all consulates around.[19] Around the 1220s, a large tower was built to defend the city, which was then called Seyne-la-Grande-Tour. A regional council took place in 1267.[18] The Saint-Jacques Hospital was founded in 1293, followed at the end of the 15th century by the Hôtel-Dieu.[21]

The death of Queen Jeanne I opened a succession crisis at the head of the Comté de Provence, the towns of the Union of Aix (1382-1387), supporting Charles, Duke of Durazzo against Louis I, Duke of Anjou. The community supported the Durazzo side until 18 September 1385, and then changed camp to join the Angevins through the patient negotiations of Marie de Blois, Louis I's widow and regent of their son Louis II.[22] The surrender of Seyne involved the communities of Couloubrous and Beauvillars.[23]

The fair, which was held at Seyne at the end of the Middle Ages, benefitted from the crossroads location, and continued until the end of the Ancien Régime.[24][25] Seyne was a baillie which subsequently became a seneschal headquarters: This included the ommunities of Auzet, Barles, La Bréole, Montclar, Pontis, Selonnet, Saint-Martin-lès-Seyne, Saint-Vincent, Ubaye, Verdaches, Le Vernet.[26]

The community of Beauvillars had 88 feus at the enumeration of 1316.[19] It depended administratively upon Seyne.[27] In the 15th century, the inhabitants of Beauvillars, who wanted to empower themselves, were massacred, the survivors deported, and the name of Beauvillars erased from the archives.[2]

The community of Couloubrous (Colobrosium, cited in the 13th century), is also attached to 15th century Seyne.[28] There were 19 feus in 1316,[19] and it also had a consulate.[29]

Early modern (1483-1789)

With the creation of the printing press, writings and ideas spread, and in the middle of the 16th century, Protestantism was implanted in Seyne. Through the Edict of Amboise (1563), adherents of this religion were allowed to build a temple, but away from the city.[30]

The town was captured and looted by the Protestant captain Paulon de Mauvans in the summer of 1560, during the Wars of Religion.[31] The town was again attacked by Protestants in 1574,[32] who retained it thereafter. The Baron of Germany hid here in 1585, before the offensive of the Catholic League,[33] without preventing the capture of the city by the Duke of Épernon.[34] During the siege, the bell tower was destroyed.[35] At the end of the Wars of Religion, Lesdiguières established a camp where he prepared his campaign for the reconquest of Provence, against the Catholic Leaguers.[36]

The reformation had despite these fights some success in Seyne, and a part of the inhabitants remained Protestant. The Protestant community remained into the 17th century around his temple, through the Edict of Nantes (1598). However, the abolition of the edict of Nantes (1688) was fatal, and the community disappeared, the people either emigrated or members were converted by force.[37]

In 1656, the two hospitals (Hôtel-Dieu and hospital Saint-Jacques) merged into a single institution. The two were relocated to a single building in 1734.[21]

In 1690, the Marquis de Parelle led the Piedmontaise army of 5,000 men which descended from the Ubaye Valley and besieged Seyne. The city was obliged to negotiate, the medieval enclosure was insufficient to ensure his defence, and the ransom was set at 11,000 livres. However, with the rise of the militia of Provence and the regiment of Alsace they were driven back.[38] On 24 December, funds were unblocked and new bastions built by Niquet, the new enclosure completed in August 1691 leaving the great tower outside of the city, but enhanced.[39]

After the more serious alert of 1692, the entire Alpine border was reconsidered by Vauban. On tour in December 1692, he asked for the construction of a citadel including the great tower. Richerand led the work from 1693 to 1699. Although not satisfied during his trip of inspection in 1700, Vauban failed to modify the fortifications, in part by building redoubts of setbacks in the north. The annexation of Ubaye by the Treaty of Utrecht took away enough of the threat, for the work to be pushed back indefinitely[40] (except for repairs to the walls in 1786).[41] In this state, the city was occupied by the Austro-Sardes in 1748 (War of the Austrian Succession) and in 1815, at the end wars of the Empire.[42] The place was almost disarmed at the end of the Ancien Régime, it had nine guns served by a garrison of three invalids, and an arsenal of 93 guns.[41]

The city was the seat of a viguerie until the French Revolution[43] and an office of the Poste Royale at the end of the Ancien Régime.[44]

French Revolution

Shortly before the French Revolution, unrest mounted. In addition to the fiscal problems of several years, the harvest of 1788 was bad and the winter of 1788-89 was very cold. The election of the Estates-General of 1789 had been prepared by those States of Provence in 1788 and in January 1789, which had contributed to highlight the political oppositions of class and cause some agitation.[45] At the end of March, at the time of the drafting of the Cahiers de doléances, an insurrectional wave shook Provence. A wheat riot occurred at Seyne, on 29 March.[46] Peasants[47] gathered, protesting with cries and threatening the wealthy. However, the riot went no further, and caused no change, unlike others in the region.[48] As a first step, the reaction consisted in gathering of the Maréchaussée staff on-site. Then lawsuits were commissioned by the Parliament of Provence, but convictions were not executed. The lack of convictions was provoked by the Storming of the Bastille along with the troubles of the Great Fear, by way of appeasement, an amnesty occurred in early August.[49]

The news of the Storming of the Bastille was welcomed, this event announced the end of royal arbitrariness and, perhaps, the most profound changes in the organization of France. Immediately after the arrival of the new regime, a great phenomenon of collective fear seized France, for fear of the conspiracy of the aristocrats who wished to recover their privileges. Rumours of troops in arms devastating everything in their path propagated at high speed, causing shots of weapons, the organization of militias and anti-nobility violence. This Great Fear came from Tallard, and awareness of the fear of the Mâconnais reached Seyne on the evening of 31 July 1789.[50] The consuls of Turriers and Bellaffaire, being warned by those at Gap that a troop of 5-6,000 brigands was headed to Haute-Provence after having plundered the Dauphiné, transmitted the news to the consuls of Seyne.[41] Immediately put on alert by the rumor, the consuls of Seyne transmitted the news to Sisteron[41] and Digne, thereby spreading the Great Fear.[50] They also prevented all parishes within the purview of the viguerie of Seyne, and sent messengers to Gap and Embrun to ask news.[41] The arsenal of the Citadel of Seyne was requisitioned, and 93 guns and nine cannons were distributed to Seyne and the villages of Saint-Pons, Selonnet and Chardavon. Men came to take refuge with their furniture and their livestock away from the walls of the citadel.[41]

In the night, messengers from Rochebrune and La Motte confirmed 'News', and add that Romans had been sacked. From the south, disquieting news arrived on the occupation of Castellane by 4,000 Barbets and the advance of 1,000 Piedmont in the Durance Valley. On 2 August, the panic declined, with the facts being clarified from the earlier rumours. However, a significant change took place. All communities Department were to be armed, organized to defend themselves and to defend their neighbours. A sense of solidarity was born within communities and between neighbouring communities, and the consuls usually decided to maintain the National Guard on foot. As soon as the fear had settled, the authorities recommended to disarm workers and landless peasants, and to keep only the owners of land and businesses in the National Guard.[41]

The patriotic society of the municipality was created during summer of 1792.[51]

19th century

Seyne gained some industrialization in the 19th century, with the development of textile industries.[19]

As with many municipalities of the Department, Seyne acquired schools well before the Jules Ferry laws. In 1863, it had five, the main town and also installed in the villages of Pompiery, Bas-Chardavon, Pons and Couloubroux. These schools provided a primary education for boys.[52] In the main town, a school for girls was imposed by the Falloux Laws of 1851.[53] The commune took advantage of subsidies from the second Duruy Law (1877) to rebuild or renovate its schools. Only the Bas-Chardavon school was not addressed.[54]

Politics and administration

List of mayors

| Start | End | Name | Party | Other details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 1945 | Yves Ramus[55] | |||

| 1977 | 1989 | Guy Derbez[56] | UDF | |

| March 1989 | 2008 | Francis Hermitte[57] | PS | Ineligible for re-election in 2008 |

| March 2008 | 2014 | André Salloum[58] | UMP | |

| April 2014 | Current (as of 21 October 2014) | Francis Hermitte[57][59] | PS | Doctor |

Environmental policy

Seyne is classified as a flower in the towns and villages floral competition.

Administration

A brigade of the National Gendarmerie is located in the main town of Seyne.[60]

Population and society

Demography

Demographic evolution

In 2012, Seyne had 1419 inhabitants (with stagnation since 1999). From the 21st century, communes with less than 10,000 inhabitants have the census held every five years (2004, 2009 and 2014, etc. for Seyne). Since 2004, the other figures are estimates.

In 2008, the commune was ranked in the 6,862nd position at the national level, while it was in the 6,215th position in 1999, and 22nd at the departmental level of 200 communes.

| Historical population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer for the Ancien Régime; EHESS; INSEE from 1968 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The demographic history of Seyne, after the loss of population of the 14th and 15th centuries, and the long period of growth until the beginning of the 19th century, is marked by a period of 'spread' where the population remained relatively stable at a high level. This period lasts from 1821 to 1861. The rural exodus then causes a movement of long-term demographic decline. By 1921, the town had lost more than half its population from the maximum of 1846.[61] The downward movement continued until the 1970s. Since then, the population growth has resumed but without returning to the level of 1911.

Age pyramid

The population of the commune is relatively old. The rate of people over 60 years age (34.1%) is higher than the national rate (21.6%) and the departmental rate (27.3%). Like national and departmental allocations, the female population of the commune is greater than the male population. The rate (52.2%) is of a similar order of magnitude as the national rate (51.6%).

The distribution of the population of the commune by age is, in 2007, as follows:

- 47.8% of men (0–14 years = 18.4%, 15–29 years = 12.1%, 30-44 year olds = 17.1%, 45–59 years = 20.1%, more than 60 years = 32.3%)

- 52.2% of women (0–14 years = 15.7%, 15–29 years = 10.5%, 30-44 year olds = 17.2%, 45–59 years = 20.8%, more than 60 years = 35.8%)

Education

The municipality has three educational institutions:

Health

A local hospital is located in the municipality.[64]

Economy

The economy of Seyne revolves around sports activities and tourism.[65]

Industry

Alp'entreprise, active in the building and public works (BTP) sector, has 15 employees.[66]

Tourism

The commune has a downhill ski station at Le Grand Puy and a Nordic skiing station at Col du Fanget. Formerly, the town had one or two ski lifts to Col Saint-Jean.

The long-distance trail 6, connecting Sainte-Foy to Saint-Paul-sur-Ubaye, crosses Seyne.

Local culture and heritage

Sites and monuments

Fortifications

Medieval fortifications remain:

- The fortified gate of the Rue Basse, from the 14th century.[67]

- The Tour Maubert, or great tower, a three-storey tower[68] built outside the walls in the 12th century. Ths was built to a rectangular plan, 12 metres (39 ft) high, it was connected to the town.[69] It has been reviewed as under restoration.[68]

The rest of the enclosure in fact consisted of the walls of the houses, built continuously, without openings to the outside.[70]

In 1690-1691, the engineer Niquet had begun new, much larger, enclosure works with nine bastion towers, of which six survive.[71] These towers were at two levels, the lower level was set to a pentagonal plan, which was an innovation of Niquet.[72] These works were reviewed by Vauban, who requested the addition of a citadel during his visit in 1692. The Citadel of Seyne was built by Richerand, from 1693, and completed in 1700.[71] This citadel, too narrow, known as Vauban but which did not satisfy him during his inspection trip,[71] dominates the Blanche Valley. 200 metres (660 ft) long by 50 metres (160 ft) wide, it incorporates an old tower modified to accommodate artillery, is equipped with a barracks, and its entry was forbidden, on the side of the town, by a tenaille.[73] The enclosure, meanwhile, was completed in 1705.[68]

The stronghold, in the front line at the time of its construction, was found in the third line after the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), which reunited the Ubaye Valley with France, was defended by two invalid companies to the Revolution, and a reduced garrison during the period between 1790-1815. The restoration added an advanced battery[73] or hornwork, a rebuilt door (1821), and added some casemates for rear firing and caponiers.[68] It was decommissioned in 1866, then occupied by a single guard from 1887 to 1907 before being sold.[74] Passed from hand to hand, the commune bought it in 1977, and has since begun restoration work. The enclosure is a listed historic monument.[75]

Civil architecture

Several houses, of the streets of the old centre, date from the 17th century, including the old town hall (main street) and a house nearby from 1788, which has an arched gate. Another house, which has always been on the high street, dates from 1605. A further house on the high street dates from 1708 and, nearby, a further one from the end of the Middle Ages, of which the overhang is supported by consoles of wood mouldings.[76] Other houses of the high street, retained in front of the arches, have characteristic medieval elements. However, these date to the 18th century.[77]

The hospital was built in 1734.[78] A carved bench, leather seat, and a five foot long table of beech, from the 17th and the 18th centuries, which are currently kept at the Town Hall, originally came from the hospital.[79] These items are classified as historic monument objects.[80][81]

Several farms in the commune are fortified.

The Church of Our Lady of Nazareth

The Church of Our Lady of Nazareth (Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth), Romanesque style, has completely retained its primitive appearance.[82] Legendarily attributed to Charlemagne, the actual construction of the present building can be traced back to the middle of the 12th century.[83] The western façade is decorated with a large rose window with twelve rays.[84] It is also decorated with a sundial, composed on a marble slab, dating from 1878.[85] The old porch has disappeared.[86] Its arching portal has retained its carved capitals.[35] The nave, 8.5 metres (28 ft) long and 14.5 metres (48 ft) high,[35] is composed of three arched barrel bays,[83] and is separated with a double-roll of a double-arch.[87] The choir has a flat chevet and is also barrel-vaulted. Before the choir, two side chapels form a false transept.[83] The portal of the south façade is Gothic (beginning from the 13th or 14th century). It has the distinction of being framed by two separations of arches which rely on the surrounding buttresses.[35] The gate leaves date to 1631.[88] The spire was rebuilt after the siege of the Duke of Épernon. Some works of consolidation (repointing, restoration of the southwestern buttresses) were made in 1967.[35]

The capitals are carved human faces and characters with the bodies twisted by the torments that devils impose upon them.[83] The baptismal fonts are 4 metres (13 ft) diameter. The church is a classified historic monument since 1862.[89]

The Holy Family altarpiece was painted directly onto the panel of the retable, in archaic style, during the 17th century.[90] The wood carved decorated pulpit, dating back to the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries[91] is classified.[92]

The furniture of the church includes:

- Several processional crosses, which one of silver is decorated with Champlevé enamels, (classified, 16th century)[93]

- A wood carving in high relief of Mary Magdalene, and golden (18th century, classified)[94]

- The altar and the tabernacle of the convent of the Dominicans, in gilded wood, the (17th century, classified)[95]

- A picture of the Holy family (16th century, classified)[96]

- A font in marble of Maurin (17th century, classified)[97]

- A tabernacle placed under a baldaquin at six feet, coming from the convent of the Trinitarians (16th century, classified)[98]

Finally, the priest has full vestments (chasuble, dalmatic, clevis, veil covering the chalice, purse, stole, maniple), satin brocaded, with colourful ornaments, and with an undecorated cross of a landscape, from the 18th century. This is a unique set for the Department,[99] and is also classified as an historic monument object.[100]

Dominican Church

The Church of the Dominicans, of classic style, is built on a relatively complex plan. In the nave with six bays, each wide span is followed by a narrow span, all flattened and barrel-vaulted. The narrow spans were filled with an oeil-de-boeuf, the wide aisles are square bays.[101]

The six reliquary busts, from the 17th century, are still archaic style[102] and are classified as historic monument objects.[103] The church is decorated with a Crucifixion of the 17th century, where Christ is surrounded by all the instruments of the Passion and with two penitents and two angels,[104] and is also classified.[105] The convent, which forms part of the church, was built in 1683 and is a registered monument.[106] The veil of the Saint-Sacrement of the church is golden embroidered silk (67 cm by 71 cm). It represents two angels in prayer on either side of an altar on which a silver lamb is sacrificed.[107] This veil has been a classified object since 1908.[108]

Chapels

The town still has many chapels:

- That of the Penitents, with a three-sided steeple, from the 17th-18th century.

- The chapel of Saint-Pons, in Saint-Pons (from the beginning of the 17th century, with a nave of five bays[109] and a Gothic bell tower of 1437),[110] whose furniture includes a silver chalice from the 17th century, which is a classified historic monument object.[111]

- The chapels of the hamlets of Bas-Chardavonet, of Haut-Chardavon, at Couloubroux, and Le Fau at Maur, at Pompiéry, at Rémusats, and of Haut-Savornin.

Museums

- Ecomuseums: The tailor, the old school, the bugade and the forge.

Events

- Each year, during the second weekend of August, the last horse competition in France is held at Seyne (a competition for the best mule, with categories).

- During the second weekend of October, an autumn fair is organized (cattle, horses, and a few other animals)

Notable people

- Antoine Laugier, born in Seyne, died in Aix in 1709, historian of the order of the Trinitarians.[112]

- The writer Jean Proal (1904-1969)

- Jacques Clarion, born October 12, 1776 in Saint-Pons, pharmacist to the Army of Italy.[113]

- The historian, Abbot Alibert

- The family of Rémusat

- Pierre Antoine Chauvet (1728-1808), Member of the Legislative, born in Seyne

- Marc-Antoine Savornin (1753-1816), Deputy to the National Convention during the French Revolution, born in Seyne

- François Massot (born June 9, 1940 in Seyne), Member of the National Assembly from the 1970s to 1990

- Eugène Michel (1821-1885), born in Seyne, Member of Parliament in 1871 and Senator from 1876 to 1885

- Pierre Martin Borély de la Sapie (1814-1895), born in Seyne, Colon in Algeria, farmer, first mayor of Boufarik (Algiers), Mayor of Blida, officer of the Légion d'honneur, general counsel of Algiers, Chairman of the USDA of Algiers Advisory Committee, Member of many commissions. See also: Boufarik: a page of colonization of Algeria, Colonel Trumelet

- Sylvain Wojak, mannequin, writer

Heraldry

|

Azure three-column rows in base topped by a cross potent between four crosses, all of gold.[114] |

See also

- Communes of the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department

- List of ancient communes in Alpes-de-Haute-Provence

Further reading

- Delmas, Jacques (1904). Essai sur l'histoire de Seyne [An essay on the history of Seyne] (in French) (Les éditions de Haute-Provence ed.). Marseille: Ruat (published 1993).

- Allibert, Célestin (1904). Histoire de Seyne, de son bailliage et de sa viguerie [History of Seyne, its Bailiwick and its viguerie] (2 volumes (691 and 153 pages)) (in French). Barcelonnette. 1972 edition published by Lafitte Reprints, 2005 edition published by MG Micberth.

- An article on different educational projects by both authors above: Frangi, Marc (2006). Seyne et ses deux histoires [Seyne and its two histories]. Chroniques de Haute-Provence (in French). Bulletin de la Société scientifique et littéraire des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. pp. 130–142.

Bibliography

- Collier, Raymond (1986). La Haute-Provence monumental et artistique [The monumental and artistic Haute-Provence] (in French). Digne: Imprimerie Louis Jean.

- Baratier, Édouard; Duby, Georges; Hildesheimer, Ernest (1969). Atlas historique. Provence, Comtat Venaissin, principauté d’Orange, comté de Nice, principauté de Monaco [Historical Atlas. Comtat Venaissin, Principality of Orange, County of Nice, Provence, Principality of Monaco] (in French). Paris: Librairie Armand Colin. (BnF no. FRBNF35450017h)

- Lechenet, Franck (2007). Plein Ciel sur Vauban [The sky on Vauban] (in French). Editions Cadré Plein ciel. pp. 220–221. ISBN 978-2-9528570-1-7.

References

- 1 2 "Canton de Seyne - Le Trésor des régions". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 de La Torre, Michel (1989). Alpes-de-Haute-Provence: le guide complet des 200 communes [Alpes de Haute Provence: The complete guide to the 200 communes] (in French). Paris: Deslogis-Lacoste. ISBN 2-7399-5004-7.

- ↑ Overal, Bernard (2012). Seyne et sa flore. Chroniques de Haute-Provence. 132. Revue de la Société scientifique et littéraire des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. p. 130. ISSN 0240-4672.

- ↑ "La Blanche (X0500640)". Sandre. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Dossier départemental sur les risques majeurs dans les Alpes-de-Haute-Provence". Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. 2008. p. 39. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012.

- 1 2 "Notice communale". Ministère de l’Écologie, du développement durable, des transports et du logement (Gaspar database). Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Dossier départemental sur les risques majeurs dans les Alpes-de-Haute-Provence". Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. 2008. p. 37. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012.

- 1 2 "Dossier départemental sur les risques majeurs dans les Alpes-de-Haute-Provence". Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. 2008. p. 98. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "Dossier départemental sur les risques majeurs dans les Alpes-de-Haute-Provence". Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. 2008. p. 80. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "Liste des communes pour votre recherche" [List of communes for your search] (in French). DICRIM. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "Épicentres de séismes lointains (supérieurs à 40 km) ressentis à Seyne" [Epicentres of distant earthquakes (above 40 km) felt in Seyne]. Sisfrance (in French). BRGM. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "fiche 40092". Sisfrance. BRGM. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "fiche 40163". Sisfrance. BRGM. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Rostaing, Charles (1973). Essai sur la toponymie de la Provence (depuis les origines jusqu’aux invasions barbares) [An essay on the Geographic Names of Provence (from the origins to the barbarian invasions)] (in French). Marseille: Laffite Reprints. pp. 243–244. (1st édition 1950).

- ↑ Fénié, Bénédicte; Fénié, Jean-Jacques (2002). Toponymie provençale [Provencal Toponymy] (in French). Éditions Sud-Ouest. p. 31. ISBN 978-2-87901-442-5.

- ↑ Baratier, Édouard; Duby, Georges; Hildesheimer, Ernest (1969). Atlas historique. Provence, Comtat Venaissin, principauté d’Orange, comté de Nice, principauté de Monaco [Historical Atlas. Comtat Venaissin, Principality of Orange, County of Nice, Provence, Principality of Monaco] (in French). Paris: Librairie Armand Colin. Carte 12 : Peuples et habitats de l’époque pré-romaine. (BnF no. FRBNF35450017h)

- ↑ Géraldine Bérard, Carte archéologique, p. 452.

- 1 2 de Loye, Augustin (1849). Des Édenates et de la ville de Seyne en Provence. 10. Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. p. 400.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer, p. 200

- ↑ Gouron, André (1963). "Diffusion des consulats méridionaux et expansion du droit romain aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles" [Dissemination of southern consulates and expansion of Roman law in the 12th and 13th centuries] (in French). Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. p. 37.

- 1 2 Collier, Raymond (1986). La Haute-Provence monumentale et artistique [Monumental and artistic Haute-Provence] (in French). Digne: Imprimerie Louis Jean. p. 434. 559 p.

- ↑ Xhayet, Geneviève (1990). "Partisans et adversaires de Louis d'Anjou pendant la guerre de l'Union d'Aix" [Supporters and opponents of Louis of Anjou during the War of the Aix Union]. Provence historique (in French). Fédération historique de Provence. 40 (162): 417–418 and 419. "Autour de la guerre de l'Union d'Aix".

- ↑ Geneviève Xhayet, p. 425.

- ↑ Louis Stouff, « carte 86 : Port, routes et foires du XIIIe au XVe siècles », in Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer

- ↑ Baratier et Hilsdesheimer, « carte 122 : Les foires (1713-1789) », in Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer

- ↑ de Loye, p. 404-405.

- ↑ Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer, p. 164.

- ↑ Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer, p. 172.

- ↑ Édouard Baratier, « carte 45 : Les consulats de Provence et du Comtat (XIIe-XIIIe siècles) », in Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer, Atlas historique de la Provence….

- ↑ Isnard, Yvette (2012). "Les dynasties seigneuriales d'Oraison". Chroniques de Haute-Provence (in French). Digne-les-Bains: Société littéraire et scientifique des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence (368): 34.

- ↑ Cru, Jacques (2001), Histoire des Gorges du Verdon jusqu’à la Révolution [History of the Verdon Gorges to the Revolution] (in French), Édisud et Parc naturel régional du Verdon, p. 195, ISBN 2-7449-0139-3

- ↑ Jacques Cru, p. 200.

- ↑ Jacques Cru, p. 202.

- ↑ "XVe journée archéologique". Annales de Haute-Provence (308): 17. 1989.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Raymond Collier, p. 89.

- ↑ Yvette Isnard, p. 40.

- ↑ Édouard Baratier, « Les Protestants en Provence », cartes 118 et 119 et commentaire dans Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer

- ↑ Ribière, Henri (1992). Vauban et ses successeurs dans les Alpes de Haute-Provence [Vauban and his successors in the Alpes de Haute-Provence] (in French). Paris: Association Vauban. p. 94. "Colmars-les-Alpes" Amis des forts Vauban de Colmars et Association Vauban.

- ↑ Guy Silve, p. 82.

- ↑ Guy Silve, p. 82-83.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gauvin, G. (1905–1906). Annales des Basses-Alpes. XII. La grande peur dans les Basses-Alpes.

- ↑ Guy Silve, p. 83-84.

- ↑ "La Révolution dans les Basses-Alpes". bulletin de la société scientifique et littéraire des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. 108 (307): 107. 1989. Annales de Haute-Provence.

- ↑ Lauga, Émile (1994). La poste dans les Basses-Alpes, ou l’histoire du courrier de l’Antiquité à l’aube du XXe siècle [Mail in the Lower Alps, or the history of old mail to the dawn of the 20th Century] (in French). Digne-les-Bains: Éditions de Haute-Provence. p. 58. ISBN 2-909800-64-4.

- ↑ Cubells, Monique (1986). "Les mouvements populaires du printemps 1789 en Provence". Provence historique. 36 (145): 309.

- ↑ M. Cubells, p. 310 and 312.

- ↑ M. Cubells, p. 313.

- ↑ M. Cubells, p. 316.

- ↑ M. Cubells, p. 322.

- 1 2 Michel Vovelle, « Les troubles de Provence en 1789 », carte 154 et commentaire, in Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer

- ↑ Alphand, Patrice (1989). "La Révolution dans les Basses-Alpes, Annales de Haute-Provence". bulletin de la société scientifique et littéraire des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. 108 (307): 296–297. Les Sociétés populaires.

- ↑ Labadie, Jean-Christophe (2013). Les Maisons d’école. Digne-les-Bains: Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. p. 9. ISBN 978-2-86-004-015-0.

- ↑ Labadie, p. 16.

- ↑ Labadie, p. 11.

- ↑ "La Libération". Basses-Alpes 39-45. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Guy Derbez is one of 500 elected representatives who sponsored the candidacy of Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (UDF) in the presidential election of 1981 "liste des élus ayant présenté les candidats à l'élection du Président de la République". Journal officiel de la République française. Conseil constitutionnel: 1061. 15 April 1981.

- 1 2 Francis Hermitte est candidat aux municipales. La Provence. 13 January 2013. p. 11.

- ↑ "Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, De Saint-Jurs à Soleihas (sic) (liste 7)". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Liste des maires" (PDF). Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "Carte des Brigades de Gendarmerie" (PDF). Groupement de gendarmerie départementale des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Préfecture des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Vidal, Christiane (1971). "Chronologie et rythmes du dépeuplement dans le département des Alpes de Haute-Provence depuis le début du XIX' siècle." [Chronology and depopulation of rhythms in the Alpes de Haute-Provence since the beginning of the nineteenth century.] (in French). 21 (85). Provence historique: 288.

- ↑ "Liste des écoles de la circonscription de Sisteron". Inspection académique des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Archived from the original on 31 October 2010.

- ↑ "Liste des collèges publics". Inspection académique des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Archived from the original on 31 October 2010.

- ↑ "Accueil" [Welcome] (in French). Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "SOLIDARITE A SEYNE LES ALPES". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Alp'entreprise". Chambre de commerce et d'industrie des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Collier, p. 308

- 1 2 3 4 "Notice no IA04000043". Base Mérimée. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 322

- ↑ "fortification d'agglomération". Base Mérimée. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 Raymond Collier, p. 323

- ↑ "fortification d'agglomération dite enceinte médiévale". Base Mérimée. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 Raymond Collier, p. 324

- ↑ Guy Silve, p. 84

- ↑ "Citadelle (ancienne)". Base Mérimée. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 369

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 369-370

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 370

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 518

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - table". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - banquette". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 4 Raymond Collier, p. 88.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 80

- ↑ Homet, Jean-Marie; Rozet, Franck (2002). Cadrans solaires des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Aix-en-Provence: Édisud. p. 101. ISBN 2-7449-0309-4.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 81.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 75.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 519.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques". base Mérimée. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 477.

- ↑ Raymond Collier,p. 517.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - chaire à prêcher". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - croix de procession". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - haut-relief : sainte Madeleine". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - autel, tabernacle". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture=. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - tableau : sainte famille (la)". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - bénitier". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - autel (maître-autel)". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 531.

- ↑ "Monuments historiques - chape, dalmatiques (2), chasuble". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 229.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 470.

- ↑ "bustes-reliquaires (6) : saint Placide, saint Prospère, sainte Candide, sainte Victoire, saint Justinien, saint Lucidius". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 478.

- ↑ "tableau : Christ et les instruments de la passion entre deux anges et deux Pénitents (le)". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Couvent des Dominicains (ancien)". Base Mérimée. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Labadie, Jean-Christophe (2013). Des Anges [The Angels]. catalogue de l’exposition à la cathédrale Saint-Jérôme (5 juillet-30 septembre 2013) (in French). Digne-les-Bains: Musée départemental d’art religieux. p. 21. ISBN 978-2-86004014-3.

- ↑ "Historic Monuments: Veil of the Blesses Sacrament". Base Palissy (in French). French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 225.

- ↑ Raymond Collier, p. 188

- ↑ "calice". Base Palissy. French Minister of Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Baratier, Duby & Hildesheimer, p. 149

- ↑ "Les grands pharmaciens : X. Les pharmaciens de Napoléon". Bulletin de la Société d'histoire de la pharmacie. 9 (30): 325. 1921.

- ↑ de Bresc, Louis (1866). Armorial des communes de Provencelanguage=fr [Armorial of the communes of Provence]. Republished, Marcel Petit CPM - Raphèle-lès-Arles 1994.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seyne. |

- The internet site of Seyne-les-Alpes

- The internet site of the Vallée de la Blanche

- An internet site of Seyne-les-Alpes and its environs, in photos

- The website of the Heritage Association of Pays du Seyne (Archive)

- The website of the local hospital of Saint Jacques