Sextus Roscius

Sextus Roscius (the younger) (fl. 1st century BC), tried in Rome for patricide in 80 BC, was defended successfully by the young Cicero in his first major litigation. The defense involved some risk for Cicero, since he accused Lucius Cornelius Chrysogonus, a freedman of Sulla, then dictator of Rome, of corruption and involvement in the crime.

Caecilia the priestess

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

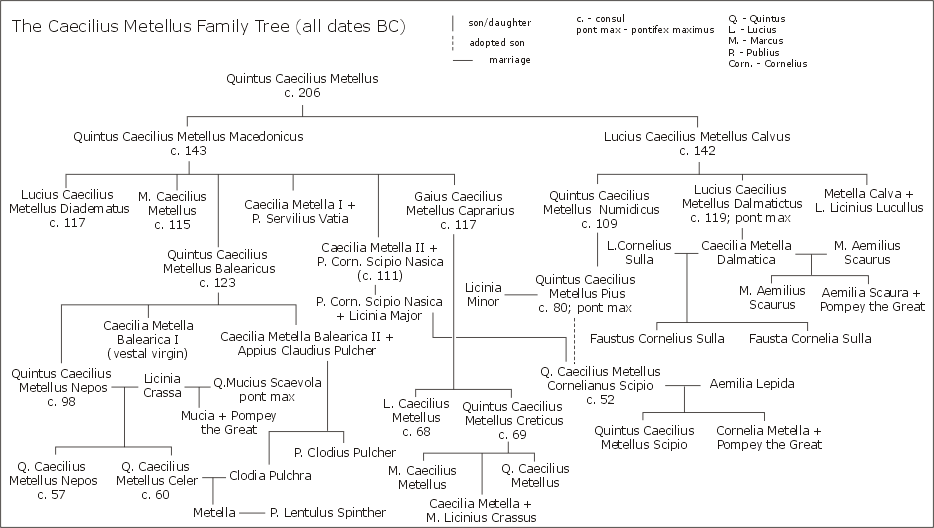

Before the trial, Roscius was sheltered by Caecilia,[1] who appears to be Caecilia Metella Balearica Major, a former Vestal Virgin by this time (since she had her own house). This Caecilia was a relative of Sulla's wife Caecilia Metella Dalmatica, and had powerful connections among the Roman elite; her intercession for the young Julius Caesar saved his life and political career. In 80 BC, the Metelli were staunchly in Sulla's camp. Her brother was Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos, a former consul whose stepdaughter Mucia Tertia was now wife of Pompey; her cousins included Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus Pius, chief ally of Sulla. Her widowed brother-in-law was Appius Claudius Pulcher, consul 79 BC as another ally of Sulla.

The Trial of Sextus Roscius for Patricide in 80 BC

(Patricide by definition means the killing of one's own father)

Cicero was a native to the Italian countryside, and Sextus Roscius was a young country boy who was accused and charged with the death of his father even though he was not in the country at the time of Sextus Roscius the Elder's death. Because of the death of his father and the accusations made against him, Sextus Roscius the Younger's properties were taken by the government and sold at an auction. "The prosecution argued that he must have hired someone else to do the deed for him, but neither produced nor named the assassin." In Cicero's first major litigation, he turned the trial around by accusing Sulla of murdering his father for political gains.Sextus Roscius is described: "Sex. Roscius the defendant (called Roscius in the commentary). He was the surviving son, at least forty years old in 80 (§39). Roscius' brother predeceased him and was said to have been the father's favorite (§42). The defendant took care of his father's numerous farms and according to Cicero preferred country life to visits to Rome or anywhere else."[2]

"Two passages from Cicero’s successful defense of Sextus Roscius of Ameria in southern Umbria. This was one of his first major cases, conducted in 80 when he was twenty-six. Chrysogonus, a freedman of Sulla, accused Roscius of parricide. In fact his father had been murdered by others, and his name then added by Chrysogonus to a proscription list(after these had been closed) in order to justify the disposal of his property. Cicero gives his defense of the son broader significance by boldly arguing to the jury of senators that Sulla’s new senate will lose public confidence if it tolerates the continuation of such disrespect for the law." Copyright | Oxford University Press | The Romans: From Village to Empire: A History of Rome from Earliest Times to the End of the Western Empire | Edition 2 |

When Cicero was defending the case of the accused, he had mentioned several names that would rid Sextus Roscius of his charges.

"If that was the object, I confess that I erred in being anxious for their success. I admit that I was mad in espousing their party, although I espoused it, O judges, without taking up arms. But if the victory of the nobles ought to be an ornament and an advantage to the republic and the Roman people,then, too, my speech ought to be very acceptable to every virtuous and noble man. But if there be any one who thinks that he and his cause is injured when Chrysogonus is found fault with, he does not understand his cause, I may almost say he does not know himself. For the cause will be rendered more splendid by resisting every worthless man. The worthless favourers of Chrysogonus, who think that his cause and theirs are identical, are injured themselves by separating themselves from such splendou" (Cic. S. Rosc. 142) [3]

References in popular culture

- The trial of Sextus Roscius is depicted in Steven Saylor's first Roma Sub Rosa mystery novel, Roman Blood.

- The trial is also depicted in Colleen McCullough's novel Fortune's Favorites, part of her Masters of Rome series.

- The trial is dramatized on the BBC documentary series Timewatch, in the episode "Murder in Rome" starring Paul Rhys as Cicero.

Notes

- ↑ Oration for Sextus Roscius of Ameria "Caecilia, the sister of Nepos, the daughter of Balearicus"

- ↑ https://www.uvm.edu/~bsaylor/latin/RosciusCommIntro.pdf

- ↑ "M. Tullius Cicero, For Sextus Roscius of Ameria, section 142". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-06.