Severe acute respiratory syndrome

| Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) | |

|---|---|

|

SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is causative of the syndrome. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | U04 |

| ICD-9-CM | 079.82 |

| DiseasesDB | 32835 |

| MedlinePlus | 007192 |

| eMedicine | med/3662 |

| Patient UK | Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| MeSH | D045169 |

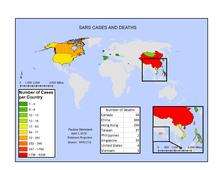

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Between November 2002 and July 2003, an outbreak of SARS in southern China caused an eventual 8,096 cases, resulting in 774 deaths reported in 37 countries,[1] with the majority of cases in Hong Kong[2] (9.6% fatality rate) according to the World Health Organization (WHO).[2] No cases of SARS have been reported worldwide since 2004.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Initial symptoms are flu-like and may include fever, myalgia, lethargy symptoms, cough, sore throat, and other nonspecific symptoms. The only symptom common to all patients appears to be a fever above 38 °C (100 °F). SARS may eventually lead to shortness of breath and/or pneumonia; either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia.

Diagnosis

SARS may be suspected in a patient who has:

- Any of the symptoms, including a fever of 38 °C (100 °F) or higher, and

- Either a history of:

- Contact (sexual or casual) with someone with a diagnosis of SARS within the last 10 days OR

- Travel to any of the regions identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as areas with recent local transmission of SARS (affected regions as of 10 May 2003 were parts of China, Hong Kong, Singapore and the town of Geraldton, Ontario, Canada).

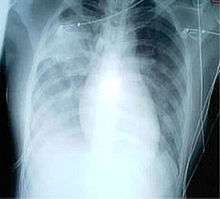

For a case to be considered probable, a chest X-ray must be positive for atypical pneumonia or respiratory distress syndrome.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has added the category of "laboratory confirmed SARS" for patients who would otherwise be considered "probable" but who have not yet had a positive chest X-ray changes, but have tested positive for SARS based on one of the approved tests (ELISA, immunofluorescence or PCR).[4]

When it comes to the chest X-ray the appearance of SARS is not always uniform but generally appears as an abnormality with patchy infiltrates.[5]

Prevention

There is no vaccine for SARS to date and isolation and quarantine remain the most effective means to prevent the spread of SARS. Other preventative measures include:

- Handwashing

- Disinfection of surfaces for fomites

- Wearing a surgical mask

- Avoiding contact with bodily fluids

- Washing the personal items of someone with SARS in hot, soapy water (eating utensils, dishes, bedding, etc.)[6]

- Keeping children with symptoms home from school

Treatment

Antibiotics are ineffective, as SARS is a viral disease. Treatment of SARS is largely supportive with antipyretics, supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation as needed.

People with SARS must be isolated, preferably in negative pressure rooms, with complete barrier nursing precautions taken for any necessary contact with these patients.

Some of the more serious damage caused by SARS may be due to the body's own immune system reacting in what is known as cytokine storm.[7]

As of 2015, there is no cure or protective vaccine for SARS that is safe for use in humans.[8] The identification and development of novel vaccines and medicines to treat SARS is a priority for governments and public health agencies around the world. MassBiologics, a non-profit organization engaged in the discovery, development and manufacturing of biologic therapies, is cooperating with researchers at NIH and the CDC developed a monoclonal antibody therapy that demonstrated efficacy in animal models.[9][10][11]

Prognosis

Several consequent reports from China on some recovered SARS patients showed severe long-time sequelae exist. The most typical diseases include, among other things, pulmonary fibrosis, osteoporosis, and femoral necrosis, which have led to the complete loss of working ability or even self-care ability of these cases. As a result of quarantine procedures, some of the post-SARS patients have been documented suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder.[12][13]

Epidemiology

SARS was a relatively rare disease, with 8,273 cases as of 2003.[14]

History

| Probable cases of SARS by country, 1 November 2002 – 31 July 2003. | ||||

| Country or Region | Cases | Deaths | SARS cases dead due to other causes | Fatality (%) |

| Canada | 251 | 44 | 0 | 18 |

| China * | 5,328 | 349 | 19 | 6.6 |

| Hong Kong | 1,755 | 299 | 5 | 17 |

| Macau | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Taiwan (Republic of China) ** | 346 | 37 | 36 | 11 |

| Singapore | 238 | 33 | 0 | 14 |

| Vietnam | 63 | 5 | 0 | 8 |

| United States | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Philippines | 14 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| Mongolia | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kuwait | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Republic of Ireland | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Romania | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Russian Federation | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spain | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South Korea | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 8273 | 775 | 60 | 9.6 |

| (*) Figures for the People's Republic of China exclude Hong Kong and Macau, which are reported separately by the WHO. | ||||

| (**) Since 11 July 2003, 325 Taiwanese cases have been 'discarded'. Laboratory information was insufficient or incomplete for 135 discarded cases; 101 of these patients died. | ||||

| Source:WHO.[15] | ||||

Outbreak in South China

The SARS epidemic appears to have started in Guangdong Province, China in November 2002 where the first case was reported that same month. The patient, a farmer from Shunde, Foshan, Guangdong, was treated in the First People's Hospital of Foshan. The patient died soon after, and no definite diagnosis was made on his cause of death. Despite taking some action to control it, Chinese government officials did not inform the World Health Organization of the outbreak until February 2003. This lack of openness caused delays in efforts to control the epidemic, resulting in criticism of the People's Republic of China from the international community. China has since officially apologized for early slowness in dealing with the SARS epidemic.[16]

The outbreak first appeared on 27 November 2002, when Canada's Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN), an electronic warning system that is part of the World Health Organization's Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), picked up reports of a "flu outbreak" in China through Internet media monitoring and analysis and sent them to the WHO. While GPHIN's capability had recently been upgraded to enable Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish translation, the system was limited to English or French in presenting this information. Thus, while the first reports of an unusual outbreak were in Chinese, an English report was not generated until 21 January 2003.[17][17][18]

Subsequent to this, the WHO requested information from Chinese authorities on 5 and 11 December. Despite the successes of the network in previous outbreak of diseases, it didn't receive intelligence until the media reports from China several months after the outbreak of SARS. Along with the second alert, WHO released the name, definition, as well as an activation of a coordinated global outbreak response network that brought sensitive attention and containment procedures (Heymann, 2003). By the time the WHO took action, over 500 deaths and an additional 2,000 cases had already occurred worldwide.[18]

In early April, after Jiang Yanyong pushed to report the danger to China,[19][20] there appeared to be a change in official policy when SARS began to receive a much greater prominence in the official media. Some have directly attributed this to the death of American James Earl Salisbury.[21] It was around this same time that Jiang Yanyong made accusations regarding the undercounting of cases in Beijing military hospitals.[19][20] After intense pressure, Chinese officials allowed international officials to investigate the situation there. This revealed problems plaguing the aging mainland Chinese healthcare system, including increasing decentralization, red tape, and inadequate communication.

Many healthcare workers in the affected nations risked and lost their lives by treating patients and trying to contain the infection before ways to prevent infection were known.[22]

Spread to other countries and regions

The epidemic reached the public spotlight in February 2003, when an American businessman traveling from China became afflicted with pneumonia-like symptoms while on a flight to Singapore. The plane stopped in Hanoi, Vietnam, where the victim died in The French Hospital of Hanoi. Several of the medical staff who treated him soon developed the same disease despite basic hospital procedures. Italian doctor Carlo Urbani identified the threat and communicated it to WHO and the Vietnamese government; he later succumbed to the disease.[23]

The severity of the symptoms and the infection among hospital staff alarmed global health authorities, who were fearful of another emergent pneumonia epidemic. On 12 March 2003, the WHO issued a global alert, followed by a health alert by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Local transmission of SARS took place in Toronto, Ottawa, San Francisco, Ulaanbaatar, Manila, Singapore, Taiwan, Hanoi and Hong Kong whereas within China it spread to Guangdong, Jilin, Hebei, Hubei, Shaanxi, Jiangsu, Shanxi, Tianjin, and Inner Mongolia.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, the first cohort of affected people were discharged from the hospital on 29 March 2003.[24] The disease spread in Hong Kong from a mainland doctor who arrived in February and stayed on the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel in Kowloon, infecting 16 of the hotel visitors. Those visitors traveled to Canada, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam, spreading SARS to those locations.[25]

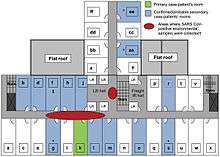

Another larger cluster of cases in Hong Kong centred on the Amoy Gardens housing estate. Its spread is suspected to have been facilitated by defects in its drainage system. Concerned citizens in Hong Kong worried that information was not reaching people quickly enough and created a website called sosick.org, which eventually forced the Hong Kong government to provide information related to SARS in a timely manner.[26]

Toronto

The first case of SARS in Toronto, Canada was identified on February 23, 2003.[27] Beginning with a woman returning from a trip to Hong Kong, the virus eventually infected 257 individuals in the province of Ontario. The trajectory of this outbreak is typically divided into two phases, with the second major wave of cases clustered around accidental exposure among patients, visitors, and staff within a major Toronto hospital. The WHO officially removed Toronto from its list of infected areas by the end of June, 2003.

The Canadian State’s official response has been widely criticized in the years following the outbreak. Brian Schwartz, vice-chair of the Ontario's SARS Scientific Advisory Committee, described public health officials’ preparedness and emergency response at the time of the outbreak as “very, very basic and minimal at best”.[28] Critics of the response often cite poorly outlined and enforced protocol for protecting healthcare workers and identifying infected patients as a major contributing factor to the continued spread of the virus. The atmosphere of fear and uncertainty surrounding the outbreak resulted in staffing issues in area hospitals when healthcare workers elected to resign rather than risk exposure to SARS.

Identification of virus

The CDC and Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory identified the SARS genome in April 2003.[29][30] Scientists at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands demonstrated that the SARS coronavirus fulfilled Koch's postulates thereby confirming it as the causative agent. In the experiments, macaques infected with the virus developed the same symptoms as human SARS victims.[31]

In late May 2003, studies were conducted using samples of wild animals sold as food in the local market in Guangdong, China. The results found that the SARS coronavirus could be isolated from masked palm civets (Paguma sp.), even if the animals did not show clinical signs of the virus. The preliminary conclusion was the SARS virus crossed the xenographic barrier from palm civet to humans, and more than 10,000 masked palm civets were killed in Guangdong Province. The virus was also later found in raccoon dogs (Nyctereuteus sp.), ferret badgers (Melogale spp.), and domestic cats. In 2005, two studies identified a number of SARS-like coronaviruses in Chinese bats.[32][33] Phylogenetic analysis of these viruses indicated a high probability that SARS coronavirus originated in bats and spread to humans either directly or through animals held in Chinese markets. The bats did not show any visible signs of disease, but are the likely natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. In late 2006, scientists from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention of Hong Kong University and the Guangzhou Centre for Disease Control and Prevention established a genetic link between the SARS coronavirus appearing in civets and humans, bearing out claims that the disease had jumped across species.[34]

Containment

The World Health Organization declared severe acute respiratory syndrome contained on 9 July 2003. In the following years, four of SARS cases were reported in China between December 2003 and January 2004. There were also three separate laboratory accidents that resulted in infection. In one of these cases, an ill lab worker spread the virus to several other people.[35][36] The precise coronavirus that caused SARS is believed to be gone, or at least contained to BSL-4 laboratories for research.

Society and culture

Community response

Fear of contracting the virus from consuming infected wild animals resulted in public bans and reduced business for meat markets throughout southern China and Hong Kong.[37] In China, Cantonese foodways, which often incorporate a wide range of meat sources, were frequently indicted as an important contributing factor to the origins of the SARS outbreak.

Toronto’s Asian minority population faced increased discrimination over the course of the city’s outbreak. Local advocacy groups reported Asians being passed over by real-estate agents and taxi drivers and shunned on public transportation.[38] In Boston and New York City, rumors and April Fools pranks gone awry resulted in an atmosphere of fear and substantial economic loss in the cities’ Chinatowns.

See also

- 2009 flu pandemic

- Bird flu

- MERS-CoV – Coronavirus discovered in June 2012 in Saudi Arabia

- Health crisis

- Jiang Yanyong

- Zhong Nanshan

- Carlo Urbani

- Public health in the People's Republic of China

- SARS conspiracy theory

- Super-spreader

- Progress of the SARS outbreak

- Bat-borne virus

References

- ↑ Smith, R. D. (2006). "Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks, Lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management". Social Science and Medicine. 63 (12): 3113–3123. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.004. PMID 16978751.

- 1 2 "Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)". NHS Choices. United Kingdom: National Health Service. 2014-10-03. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

Since 2004, there haven't been any known cases of SARS reported anywhere in the world.

- ↑ "Laboratory Diagnosis of SARS". Emerging Infectious Disease Journal. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 (5). May 2004. Retrieved 2013-07-14.

- ↑ Lu P, Zhou B, Chen X, Yuan M, Gong X, Yang G, Liu J, Yuan B, Zheng G, Yang G, Wang H (July 2003). "Chest X-ray imaging of patients with SARS". Chinese Medical Journal. 116 (7): 972–5. PMID 12890364.

- ↑ "SARS: Prevention". MayoClinic.com. 2011-01-06. Retrieved 2013-07-14.

- ↑ Dandekar, A; Perlman, S (2005). "Immunopathogenesis of coronavirus infections: implications for SARS". Nat Rev Immunol. 5 (12): 917–927. doi:10.1038/nri1732. PMID 16322745.

- ↑ Shibo Jiang; Lu Lu; Lanying Du (2013). "Development of SARS vaccines and therapeutics is still needed". Future Virology. 8 (1): 1–2. doi:10.2217/fvl.12.126.

- ↑ Greenough TC, Babcock GJ, Roberts A, Hernandez HJ, Thomas WD Jr, Coccia JA, Graziano RF, Srinivasan M, Lowy I, Finberg RW, Subbarao K, Vogel L, Somasundaran M, Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL, Ambrosino DM (15 February 2005). "Development and characterization of a severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody that provides effective immunoprophylaxis in mice". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 191 (4): 507–14. doi:10.1086/427242. PMID 15655773.

- ↑ Tripp RA, Haynes LM, Moore D, Anderson B, Tamin A, Harcourt BH, Jones LP, Yilla M, Babcock GJ, Greenough T, Ambrosino DM, Alvarez R, Callaway J, Cavitt S, Kamrud K, Alterson H, Smith J, Harcourt JL, Miao C, Razdan R, Comer JA, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Sanchez A, Rota PA, Bellini WJ, Anderson LJ (September 2005). "Monoclonal antibodies to SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV): identification of neutralizing and antibodies reactive to S, N, M and E viral proteins". J Virol Methods. 128 (1–2): 21–8. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.03.021. PMID 15885812.

- ↑ Roberts A, Thomas WD, Guarner J, Lamirande EW, Babcock GJ, Greenough TC, Vogel L, Hayes N, Sullivan JL, Zaki S, Subbarao K, Ambrosino DM (1 March 2006). "Therapy with a severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody reduces disease severity and viral burden in golden Syrian hamsters". J Infect Dis. 193 (5): 685–92. doi:10.1086/500143. PMID 16453264.

- ↑ Hawryluck, Laura (2004). "SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada." (PDF). Emerging Infectious Diseases.

- ↑ Ma Jinyu (2009-07-15). "(Silence of the Post-SARS Patients)" (in Chinese). Southern People Weekly. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- ↑ Oehler, Richard L. "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)". Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ "Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response (EPR)". World Health Organization.

- ↑ "WHO targets SARS 'super spreaders'". CNN. 6 April 2003. Retrieved 5 July 2006.

- 1 2 Mawudeku, Abla; Blench, Michael (2005). "Global Public Health Intelligence Network" (PDF). Public Health Agency of Canada.

- 1 2 Rodier, G (10 February 2004). "Global Surveillance, National Surveillance, and SARS". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10: 173–5. doi:10.3201/eid1002.031038. PMID 15040346.

- 1 2 Joseph Kahn (12 July 2007). "China bars U.S. trip for doctor who exposed SARS cover-up". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- 1 2 "The 2004 Ramon Magsaysay Awardee for Public Service". Ramon Magsaysay Foundation. 31 August 2004. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- ↑ "SARS death leads to China dispute". CNN. 10 April 2003. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ↑ Sars: The people who risked their lives to stop the virus

- ↑ http://www.who.int/csr/sars/urbani/en/

- ↑ http://www.news-medical.net/news/2004/04/24/821.aspx. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Sr. Irene Martineau". Oxford Medical School Gazette. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ↑ "Hong Kong Residents Share SARS Information Online". NPR.org. Retrieved 2016-05-11.

- ↑ "Update: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome --- Toronto, Canada, 2003". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-11.

- ↑ "Is Canada ready for MERS? 3 lessons learned from SARS". www.cbc.ca. Retrieved 2016-05-11.

- ↑ "Remembering SARS: A Deadly Puzzle and the Efforts to Solve It". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ "Coronavirus never before seen in humans is the cause of SARS". United Nations World Health Organization. 16 April 2006. Retrieved 5 July 2006.

- ↑ Fouchier RA, Kuiken T, Schutten M, et al. (2003). "Aetiology: Koch's postulates fulfilled for SARS virus". Nature. 423 (6937): 240. doi:10.1038/423240a. PMID 12748632.

- ↑ Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, et al. (2005). "Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses". Science. 310 (5748): 676–9. doi:10.1126/science.1118391. PMID 16195424.

- ↑ Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS, et al. (2005). "Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (39): 14040–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506735102. PMC 1236580

. PMID 16169905.

. PMID 16169905. - ↑ "Scientists prove SARS-civet cat link". China Daily. 23 November 2006.

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/03/11/sars-2013_n_2854568.html

- ↑ "WHO | SARS outbreak contained worldwide". www.who.int. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ↑ Zhan, Mei (2005-01-01). "Civet Cats, Fried Grasshoppers, and David Beckham's Pajamas: Unruly Bodies after SARS". American Anthropologist. 107 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1525/aa.2005.107.1.031. JSTOR 3567670.

- ↑ Schram, Justin (2003-01-01). "How Popular Perceptions Of Risk From Sars Are Fermenting Discrimination". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 326 (7395): 939–939. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7395.939. JSTOR 25454328.

Further reading

- Alan DL Sihoe; Randolph HL Wong; Alex TH Lee; Lee Sung Lau; Natalie Y. Y. Leung; Kin Ip Law; Anthony P. C. Yim (June 2004). "Severe acute respiratory syndrome complicated by spontaneous pneumothorax". Chest. 125 (6): 2345–51. doi:10.1378/chest.125.6.2345. PMID 15189961.

- War Stories, Martin Enserink, Science 15 March 2013: 1264–1268. In 2003, the world successfully fought off a new disease that could have become a global catastrophe. A decade after the SARS outbreak, how much safer are we?

- SARS: Chronology of the Epidemic Martin Enserink, Science 15 March 2013: 1266–1271. In 2003, the world successfully fought off a new disease that could have become a global catastrophe. Here's what happened from the first case to the end of the epidemic.

- Understanding the Enemy, Dennis Normile, Science 15 March 2013: 1269–1273. Research sparked by the SARS outbreak increased the understanding of emerging diseases, though much remains to be learned.

External links

| Library resources about Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to SARS. |

- Vaccine Research Center Information regarding preventative vaccine research studies

- MedlinePlus: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome News, links and information from The United States National Library of Medicine.

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Symptoms and treatment guidelines, travel advisory, and daily outbreak updates. From the World Health Organization (WHO).

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Information on the international outbreak of the illness known as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Provided by the US Centers for Disease Control

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Information on Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) – For Health Professionals from the Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Life in Hong Kong during SARS – a gallery of images reflecting daily life in Hong Kong during the 2003 SARS outbreak.

- What we can learn from SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)—Lessons for Future Pandemics

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Coronaviridae

- Other

- NIOSH Topic Area: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

- NIOSH Publication: Understanding Respiratory Protection Against SARS