Sancus

In ancient Roman religion, Sancus (also known as Sangus or Semo Sancus) was a god of trust (fides), honesty, and oaths. His cult, one of the most ancient amongst the Romans, probably derived from Umbrian influences.[1]

Oaths

Sancus was also the god who protected oaths of marriage, hospitality, law, commerce, and contracts in particular. Some forms of swearings were used in his name and honour at the moment of the signing of contracts and other important civil acts. Some words (like "sanctity" and "sanction" - for the case of disrespect of pacts) have their etymology in the name of this god, whose name is connected with sancire "to hallow" (hence sanctus, "hallowed").

Worship

The temple dedicated to Sancus stood on the Quirinal Hill, under the name Semo Sancus Dius Fidius. Dionysius of Halicarnassus[2] writes that the worship of Semo Sancus was imported into Rome at a very early time by the Sabines who occupied the Quirinal Hill. According to tradition his cult was said to have been introduced by the Sabines and perhaps king Titus Tatius dedicated a small shrine.[3] The actual construction of the temple is generally ascribed to Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, although it was dedicated by Spurius Postumius on June 5 466 BC.[4]

Sancus was considered the son of Jupiter, an opinion recorded by Varro and attributed to his teacher Aelius Stilo.[5] He was the god of heavenly light, the avenger of dishonesty, the upholder of truth and good faith, the sanctifier of agreements. Hence his identification with Hercules, who was likewise the guardian of the sanctity of oaths. His festival day occurred on the nonae of June, i.e. June 5.

The shrine on the Quirinal was described by 19th century archeologist R.A. Lanciani.[6] It was located near the Porta Sanqualis of the Servian walls,[7] not far from the modern church of San Silvestro al Quirinale, precisely on the Collis Mucialis.[8] It was described by classical writers as having no roof so as oaths could be taken under the sky.

It had a chapel containing relics of the regal period: a bronze statue of Tanaquil or Gaia Caecilia, her belt containing remedies that people came to collect, her distaff, spindle and slippers,[9] and after the capture of Privernum in 329 BC, brass medallions or bronze wheels (discs) made of the money confiscated from Vitruvius Vaccus.[10]

Dionysius of Halicarnassus records that the treaty between Rome and Gabii was preserved in this temple. This treaty was perhaps the first international treaty to be recorded and preserved in written form in ancient Rome. It was written on the skin of the ox sacrificed to the god upon its agreement and fixed onto a wooden frame or a shield.[11]

According to Lanciani the foundations of the temple were discovered in March 1881, under what was formerly the convent of S. Silvestro al Quirinale (or degli Arcioni), later the headquarters of the (former) Royal Engineers. Lanciani relates the monument was a parallelogram in shape, thirty-five feet long by nineteen wide, with walls of travertine and decorations in white marble. It was surrounded by votive altars and the pedestal of statues. In Latin literature it is sometimes called aedes, sometimes sacellum, this last appellation probably connected to the fact it was a sacred space in the open air.[12] Platner though writes its foundations had already been detected in the 16th century.

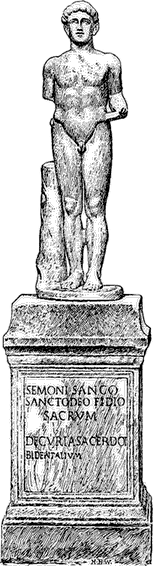

Lanciani supposes the statue depicted in this article might have been found on the site of the shrine on the Quirinal as it appeared in the antiquarian market of Rome at the time of the excavations at S. Silvestro.

There was possibly another shrine or altar (ara) dedicated to Semo Sancus on the Isle of the Tiber, near the temple of Iupiter Iurarius. This altar bears the inscription seen and misread by S. Justin (Semoni Sanco Deo read as Simoni Deo Sancto) and was discovered on the island in July, 1574. It is preserved in the Galleria Lapidaria of the Vatican Museum, first compartment (Dii). Lanciani advances the hypothesis that while the shrine on the Quirinal was of Sabine origin that on the Tiber island was Latin.

According to another source the statue of Sancus (as Semo Sancus Dius Fidus) was found on the Tiber Island.[13]

The statue is life-sized and is of the archaic Apollo type. The expression of the face and the modeling of the body however are realistic. Both hands are missing, so that it is impossible to say what were the attributes of the god, one being perhaps the club of Hercules and/or the ossifrage, the augural bird proper to the god (avis sanqualis), hypotheses made by archaeologist Visconti and reported by Lanciani. Other scholars think he should have hold lightningbolts in his left hand.

The inscription on the pedestal mentions a decuria sacerdot[um] bidentalium.[14] Lanciani makes reference to a glossa of Sextus Pompeius Festus s.v. bidentalia which states these were small shrines of lesser divinities, to whom hostiae bidentes, i.e. lambs two years old, were sacrificed. William Warde Fowler says these priests should have been concerned with lightning bolts, bidental being both the technical term for the puteal, the hole resembling a well left by strikes onto the ground and for the victims used to placate the god and purify the site.[15] For this reason the priests of Semo Sancus were called sacerdotes bidentales. They were organised, like a lay corporation, in a decuria under the presidency of a magister quinquennalis.

Their residence at the shrine on the Quirinal was located adjoining the chapel: it was ample and commodious, provided with a supply of water by means of a lead pipe.

The pipes have been removed to the Capitoline Museum. They bear the same inscription found on the base of the statue.[16]

The statue is now housed in the Galleria dei Candelabri of the Vatican Palace. The foundations of the shrine on the Quirinal have been destroyed.

Semo Sancus had a large sanctuary at Velitrae, now Velletri, in Volscian territory.[17]

Simon Magus

Justin Martyr records that Simon Magus, a gnostic mentioned in the Christian Bible, performed such miracles by magic acts during the reign of Claudius that he was regarded as a god and honored with a statue on the island in the Tiber which the two bridges cross, with the inscription Simoni Deo Sancto, "To Simon the Holy God".[18] However, in 1574, the Semo Sancus statue was unearthed on the island in question, leading most scholars to believe that Justin Martyr confused Semoni Sanco with Simon.

Family

Cato [19] and Silius Italicus[20] wrote that Sancus was a Sabine god and father of the eponymous Sabine hero Sabus. He is thus sometimes considered a founder-deity.

Origins and significance

| Religion in ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Priesthoods |

| Deities |

|

| Related topics |

Even in the ancient world, confusion surrounded this deity, as evidenced by the multiple and unstable forms of his name. Aelius Stilo[21] identified him with Hercules, but also, because he explained the Dius Fidius as Dioskouros, with Castor. In late antiquity, Martianus Capella places Sancus in region 12 of his cosomological system, which draws on Etruscan tradition in associating gods with specific parts of the sky.[22] On the Piacenza Liver the corresponding case bears the theonym Tluscv. The complexity of the theonym and the multiple relationships of the god with other divine figures shall be better examined in a systematic wise here below.

Sancus as Semo

The first part of the theonym defines the god as belonging to the category of the Semones or Semunes, divine entities of the ancient Romans and Italics.[23] In a fragment of Marcus Porcius Cato, preserved in Dionysius of Halicarnassus (II 49 1-2), Sancus is referred to as δαίμων and not θεός.

In Rome this theonym is attested in the carmen Arvale and in a fragmentary inscription.[24] Outside Rome in Sabine, Umbrian and Pelignan territory.[25] An inscription from Corfinium reads: Çerfom sacaracicer Semunes sua[d, "priest of the Çerfi and the Semones", placing side by side the two entities çerfi and semunes. The çerfi are mentioned in the Iguvine Tables in association with Mars e.g. in expressions as Çerfer Martier. Their interpretation remains obscure: an etymological and semantic relation to IE root *cer, meaning growth, is possible though problematic and debated.

According to ancient Latin sources the meaning of the term semones would denote semihomines (also explained as se-homines, men separated from ordinary ones, who have left their human condition: prefix se- both in Latin and Greek may denote segregation), or the dii medioxumi, i.e. gods of the second rank, or semigods,[26] entities that belong to the intermediate sphere between gods and men.[27] The relationship of these entities to Semo Sancus is comparable to that of the genii to Genius Iovialis: as among the genii there is a Genius Iovialis, thus similarly among the semones there is a Semo Sancus.[28] The semones would then be a class of semigods, i.e. people who did not share the destiny of ordinary mortals even though they were not admitted to Heaven, such as Faunus, Priapus, Picus, the Silvani.[29] However some scholars opine such a definition is wrong and the semones are spirits of nature, representing the generative power hidden in seeds.[30] In ancient times only offers of milks were allowed to the semones.[31]

The deity Semonia bears characters that link her to the group of the Semones, as is shown by Festus s.v. supplicium: when a citizen was put to death the custom was to sacrifice a lamb of two years (bidentis) to Semonia to appease her and purify the community. Only thereafter could the head and property of the culprit be vowed to the appropriate god. That Semo Sancus received the same kind of cult and sacrifice is shewn in the inscription (see figure in this article) now under the statue of the god reading: decuria sacerdotum bidentalium.

The relationship between Sancus and the semones of the carmen Arvale remains obscure, even though some scholars opine that Semo Sancus and Salus Semonia or Dia Semonia would represent the core significance of this archaic theology. It has also been proposed to understand this relationship in the light of that between Vedic god Indra or his companion Trita Āpya and the Maruts.[32] Eduard Norden has proposed a Greek origin.[33]

Sancus and Salus

The two gods were related in several ways. Their shrines (aedes) were very close to each other on two adjacent hilltops of the Quirinal, the Collis Mucialis and Salutaris respectively.[34] Some scholars also claim some inscriptions to Sancus have been found on the Collis Salutaris.[35] Moreover, Salus is the first of the series of deities mentioned by Macrobius[36] as related in their sacrality: Salus, Semonia, Seia, Segetia, Tutilina, who required the observance of a dies feriatus of the person who happened to utter their name. These deities were connected to the ancient agrarian cults of the valley of the Circus Maximus that remain quite mysterious.[37]

The statue of Tanaquil placed in the shrine of Sancus was famed for containing remedies in its girdle which people came to collect, named praebia.[38] As numerous statues of boys wear the apotropaic golden bulla, bubble or locket, which contained remedies against envy, or the evil eye, Robert E. A. Palmer has remarked a connexion between these and the praebia of the statue of Tanaquil in the sacellum of Sancus.[39]

German scholars Georg Wissowa, Eduard Norden and Kurt Latte write of a deity named Salus Semonia[40] who is though attested only in one inscription of year 1 A.D. mentioning a Salus Semonia in its last line (line seventeen). There is consensus among scholars that this line is a later addition and cannot be dated with certainty.[41] In other inscriptions Salus is never connected to Semonia.[42]

Sancus Dius Fidius and Jupiter

The relationship between the two gods is certain as both are in charge of oath, are connected with clear daylight sky and can wield lightning bolts. This overlap of functional characters has generated confusion about the identity of Sancus Dius Fidius either among ancient and modern scholars, as Dius Fidius has sometimes been considered another theonym for Iupiter.[43] The autonomy of Semo Sancus from Jupiter and the fact that Dius Fidius is an alternate theonym designating Semo Sancus (and not Jupiter) is shewn by the name of the correspondent Umbrian god Fisus Sancius which compounds the two constituent parts of Sancus and Dius Fidius: in Umbrian and Sabine Fisus is the exact correspont of Fidius, as e.g. Sabine Clausus of Latin Claudius.[44] The fact that Sancus as Iupiter is in charge of the observance of oaths, of the laws of hospitality and of loyalty (Fides) makes him a deity connected with the sphere and values of sovereignty, i.e. in Dumezil's terminology of the first function.

G. Wissowa advanced the hypothesis that Semo Sancus is the genius of Jupiter.[45] W. W. Fowler has cautioned that this interpretation looks to be an anachronism and it would only be acceptable to say that Sancus is a Genius Iovius, as it appears from the Iguvine Tables.[46] The concept of a genius of a deity is attested only in the imperial period.

Theodor Mommsen, William Warde Fowler and Georges Dumezil among others rejected the accountability of the tradition that ascribes a Sabine origin to the Roman cult of Semo Sancus Dius Fidius, partly on linguistic grounds since the theonym is Latin and no mention or evidence of a Sabine Semo is found near Rome, while the Semones are attested in Latin in the carmen Arvale. In their view Sancus would be a deity who was shared by all ancient Italic peoples, whether Osco-Umbrian or Latino-Faliscan.[47]

The details of the cult of Fisus Sancius at Iguvium and those of Fides at Rome,[48] such as the use of the mandraculum, a piece of linen fabric covering the right hand of the officiant, and of the urfeta (orbita) or orbes ahenei, sort of small bronze disc brought in the right hand by the offerant at Iguvium and also deposed in the temple of Semo Sancus in 329 B.C. after an affair of treason[49] confirm the parallelism.

Some aspects of the ritual of the oath for Dius Fidius, such as the proceedings under the open sky and/or in the compluvium of private residences and the fact the temple of Sancus had no roof, have suggested to romanist O. Sacchi the idea that the oath by Dius Fidius predated that for Iuppiter Lapis or Iuppiter Feretrius, and should have its origin in prehistoric time rituals, when the templum was in the open air and defined by natural landmarks as e.g. the highest nearby tree.[50] Supporting this interpretation is the explanation of the theonym Sancus as meaning sky in Sabine given by Johannes Lydus, etymology that however is rejected by Dumezil and Briquel among others.[51]

All the known details concerning Sancus connect him to the sphere of the fides, of oaths, of the respect of compacts and of their sanction, i. e. divine guarantee against their breach. These values are all proper to sovereign gods and common with Iuppiter (and with Mitra in Vedic religion).

Sancus and Hercules

Aelius Stilo's interpretation of the theonym as Dius Filius is based partly on the interchangeability and alternance of letters d and l in Sabine, which might have rendered possible the reading of Dius Fidius as Dius Filius, i.e. Dios Kouros, partly on the function of guarantor of oaths that Sancus shared with Hercules: Georg Wissowa called it a gelehrte Kombination,[52] while interpreting him as the genius, (semo) of Iupiter.[53] Stilo's interpretration in its linguistic aspect looks to be unsupported by the form of the theonym in the Iguvine Tables, where it appears as Fisus or Fisovius Sancius, formula that includes the two component parts of the theonym.[54] This theonym is rooted in an ancient IE *bh(e)idh-tos and is formed on the rootstem *bheidh- which is common to Latin Fides.

The connexion to Hercules looks to be much more substantial on theological grounds. Hercules, especially in ancient Italy, retained many archaic features of a founder deity and of a guarantor of good faith and loyalty. The relationship with Jupiter of the two characters could be considered analogous. Hence both some ancient scholars such as Varro and Macrobius and modern ones as R. D. Woodard consider them as one.

Sancus and Mars

At Iguvium Fisus Sancius is associated to Mars in the ritual of the sacrifice at the Porta (Gate) Tesenaca as one of the gods of the minor triad[55] and this fact proves his military connection in Umbria. This might be explained by the military nature of the concept of sanction which implies the use of repression. The term sanctus too has in Roman law military implications: the walls of the city are sancti.[56]

The martial aspect of Sancus is highlighted also in the instance of the Samnite legio linteata, a selected part of the army formed by noble soldiers bound by a set of particularly compelling oaths and put under the special protection of Iupiter. While ordinary soldiers dressed in a purple red paludamentum with golden paraphernalia, those of the legio dressed in white with silver paraphernalia, as an apparent show of their different allegiance and protector. This strict association of the ritual to Iupiter underlines the military aspect of the sovereign god that comes in to supplement the usual role of Mars on special occasions, i. e. when there is the need for the support of his power.[57]

A prodigy related by Livy concerning an avis sanqualis who broke a rainstone or meteorite fallen into a grove sacred to Mars at Crustumerium in 177 B. C. has also been seen by some scholars as a sign of a martial aspect of Sancus. Roger D. Woodard has interpreted Sancus as the Roman equivalent of Vedic god Indra, who has to rely on the help of the Maruts, in his view corresponding to the twelfth Roman semones of the carmen Arvale, in his task of killing the dragon Vrtra thus freeing the waters and averting draught. He traces the etymology of Semo to IE stemroot *she(w) bearing the meanings of to pour, ladle, flow, drop related to rain and sowing.[58] In Roman myth Hercules would represent this mythic character in his killing of the monstre Cacus. Sancus would be identical to Hercules and strictly related, though not identical, to Mars as purported by the old cults of the Salii of Tibur related by Varro and other ancient authors cited by Macrobius. The tricephalous deity represented near Hercules in Etruscan tombs and reflected in the wise of the killing of Cacus would correspond to the features of the monster killed by Indra in association with Trita Āpya.[59]

Sancus in Etruria

As for Etruscan religion N. Thomas De Grummond has suggested to identify Sancus in the inscription Selvans Sanchuneta found on a cippus unearthed near Bolsena, however other scholars connect this epithet to a local family gentilicium.[60] The theonym Tec Sans found on bronze statues (one of a boy and that of the arringatore, public speaker) from the area near Cortona has been seen as an Etruscan form of the same theonym.[39]

Legacy

The English words sanction and saint are directly derived from Sancus. The toponym Sanguineto is related to the theonym, through the proper name Sanquinius.[61]

References

- ↑ Compare: Latte, Kurt (1992) [1967]. "Eidgötter". In Bengtson, Hermann. Römische Religionsgeschichte. Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft (in German). 5 (2 ed.). Munich: C.H.Beck. p. 126-127. ISBN 9783406013744. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

[Dius Fidius] ist [...] bereits mit Semo Sancus gleichgesetzt, dem anderen Schwurgott, den die römische Religion kennt. Dius Fidius und Semo sind [...] in alter Zeit verschiedene Gottheiten gewesen; die Verbindung im Eide hat die beiden für die römischen Gelehrten und vielleicht nicht nur für diese zu einem Gott gemacht.[...] Er hatte einen Tempel auf dem Quirinal, [...] der im J. 466 v. Chr. geweiht ist, während man die Erbauung schon König Tarquinius zuschrieb. Da er auf dem Quirinal lag, sollte er nach anderen von den Sabinern des T. Tatius gegründet sein.

- ↑ Dion. Hal. II 49, 2.

- ↑ Ovid Fasti VI 217-8; Properce IV 9, 74; Tertullian Ad Nationes II 9, 13; Varro Lingua latina V 52: note that Sancus is not mentioned in the list of gods to whom King Tatius dedicated shrines at V 72.

- ↑ Dion. Hal. IX 60; Ovid Fasti VI 213; CIL I 2nd 319 p. 220; S. B. Platner, T. Ashby A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome London 1929 pp.469-470.

- ↑ Varro Lingua Latina V 66.

- ↑ R.A. Lanciani Pagan and Christian Rome Boston and New York 1893 pp. 32-33.

- ↑ Festus s. v. Sanqualis Porta p. 345 L.

- ↑ Varro Lingua Lat. V 52: Collis Mucialis: quinticeps apud aedem Dei Fidi; in delubro ubi aeditumus habere solet.

- ↑ Plutarch Quaestiones Romanae 30; Pliny Nat. Hist. VIII 94; Festus s. v. praebia p. 276 L: "Praebia rursus Verrius vocari ait ea remedia quae Gaia Caecilia, uxor Tarquini Prisci, invenisse existimatur, et inmiscuisse zonae suae, qua praecincta statua eius est in aede Sancus, qui deus dius fidius vocatur; et qua zona periclitantes ramenta sumunt. Ea vocari ait praebia, quod mala prohibeant."

- ↑ Livy VIII 20, 8.

- ↑ Dion. Hal. Antiquitates Romanae IV 58, 4.

- ↑ S. B. Platner A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome London 1929 p. 469.

- ↑ Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. (p. 226).

- ↑ CIL VI 568.

- ↑ W. W. Fowler The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London, 1899, p. 139.

- ↑ CIL XV 7253.

- ↑ Livy XXXII 1. 10.

- ↑ The First Apology, Chapter XXVI.—Magicians not trusted by Christians, Justin Martyr.

- ↑ In a fragment preserved by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, 2.49.2.;

- ↑ Punica VIII 421.

- ↑ As preserved by Varro, De lingua latina 5.66.

- ↑ Stefan Weinstock, "Martianus Capella and the Cosmic System of the Etruscans," Journal of Roman Studies 36 (1946), p. 105, especially note 19. Martianus is likely to have derived his system from Nigidius Figulus (through an intermediate source) and Varro.

- ↑ Martianus Capella II 156; Fulgentius De Sermone Antiquorum 11.

- ↑ CIL I 2nd 2436: Se]monibu[s. The integration is not certain.

- ↑ cf. E. Norden Aus altroemischer Priesterbuchen Lund, 1939, p. 205 ff.

- ↑ Festus s.v. medioxumi.

- ↑ Scheiffele in Pauly Real Encyclopaedie der Altertumwissenschaften s.v. Semones citing Priscianus p. 683; Fulgentius De Sermone Antiquorum 11; Festus s.v. hemona; Varro (unreferenced) from semideus; Hartung I. 41: from serere and Sabine Semones half-self, more like genii; also Gdywend Mythologie bei der Romer par. 261: in Sabine, godly people, maybe Lares. Besides all the dii medioxumi belong to this category.

- ↑ Pauly above.

- ↑ cf. Ovid Metamorphoses I 193-195.

- ↑ Dahrenberg & Saglio Dictionnaire des Antiquites Grecques et Romaines s.v. Semo Sancus.

- ↑ U. Pestalozza Iuno Caprotina in "Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni" 1934 p. 64, citing Nonius Marcellus De Compendiosa Doctrina (Müller) I p. 245: "Rumam veteres dixerunt mammam. Varro Cato vel De liberis educandis: dis Semonibus lacte fit, non vino; Cuninae propter cunis, Ruminae propter rumam, id est, prisco vocabulo, mammam...". "Studi e materiali di storia delle religioni" 1934.

- ↑ G.B. Pighi La preghiera romana in AA. VV. La preghiera Roma, 1967 pp. 605-606; Roger D. Woodard Roman and Vedic sacred space Chicago, 2006, p. 221 ff.

- ↑ Classical Review 1939.

- ↑ Varro Lingua Latina V 53

- ↑ Jesse B. Carter in Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics vol. 13 s.v. Salus

- ↑ Macrobius Saturnalia I 16,8

- ↑ G. Dumezil ARR Paris 1974, I. Chirassi Colombo in ANRW 1981 p.405; Tertullian De Spectculis VIII 3.

- ↑ Festus s.v. praebia; Robert E. A. Palmer "Locket gold, lizard green" in Etruscan influences on Italian Civilisation 1994

- 1 2 R. E. A. Palmer "Locket Gold Lizard Green" in J. F. Hall Etruscan Influences on the Civilizations of Italy 1994 p. 17 ff.

- ↑ G. Wissowa Roschers Lexicon s.v. Sancus, Religion und Kultus der Roemer Munich 1912 p. 139 ff.; E. Norden Aus der altrömischer Priesterbüchen Lund 1939 p. 205 ff.; K. Latte Rom. Religionsgechichte Munich 1960 p. 49-51.

- ↑ Salus Semonia posuit populi Victoria; R.E.A. Palmer Studies of the northern Campus Martius in ancient Rome 1990.

- ↑ Ara Salutus from a slab of an altar from Praeneste; Salutes pocolom on a pitcher from Horta; Salus Ma[gn]a on a cippus from Bagnacavallo; Salus on a cippus from the sacred grove of Pisaurum; Salus Publica from Ferentinum.

- ↑ G. Dumezil La religion Roamaine archaïque Paris, 1974; It. tr. Milan 1977 p.189.

- ↑ Irene Rosenzweig The Ritual and Cults of Iguvium London, 1937, p. ; D. Briquel above; E. Norden above.

- ↑ G. Wissowa in Roschers Lexicon 1909 s.v. Semo Sancus col. 3654; Religion und Kultus der Römer Munich, 1912, p. 131 f.

- ↑ W. W. Fowler The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London, 1899, p. 189.

- ↑ La religion romaine archaïque It. tr. Milano, 1977, p. 80 n. 25, citing also G. Wissowa in Roschers Lexicon s.v. Sancus, IV, 1909, col. 3168; Dumezil wholly rejects the tradition of the synecism of Rome.

- ↑ cf.Livy I 21, 4; Servius Aen. I 292 on this prescription of Numa's.

- ↑ Livy VIII 20, 8; W. W. Fowler The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London 1899 p. 138; Irene Rosenzweig Ritual and Cult in Pre-Roman Iguvium London, 1937, p.210; D. Briquel "Sur les aspects militaires du dieu ombrien Fisus Sancius" in MEFRA 1979 p. 136.

- ↑ O. Sacchi "Il trivaso del Quirinale" in Revue Internationale de Droit de l'Antiquite' 2001 pp. 309-311, citing Nonius Marcellus s.v. rituis (L p.494): Itaque domi rituis nostri, qui per dium Fidium iurare vult, prodire solet in compluvium., 'thus according to our rites he who wishes to swear an oath by Dius Fidius he as a rule walks to the compluvium (an unroofed space within the house)'; Macrobius Saturnalia III 11, 5 on the use of the private mensa as an altar mentioned in the ius Papirianum; Granius Flaccus indigitamenta 8 (H. 109) on king Numa's vow by which he asked for the divine punishment of perjury by all the gods

- ↑ Lydus de Mensibus IV 90; G. Capdeville "Les dieux de Martianus Capella" in Revue de l'histoire des religions 1995 p.290.

- ↑ G. Wissowa Above.

- ↑ Wiliam W. Fowler The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London, 1899, p. 136 who is rather critical of this interpretation of Wissowa's.

- ↑ W. W. Fowler The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London, 1899, p. 137; Irene Rosenzweig Ritual and Cult of Pre-Roman Iguvium London, 1937 p. 275 as quoted by E. Norden Aus altroemischer Priesterbuchen Lund, 1939, p. 220 : "Iupater Sancius is identical with Semo Sancus Dius Fidius of the Latins. Here we see Fisus Sancius who originally was an attribute of Iupater himself in his function of the guardian of Fides, to develop into a separate god with a sphere of his own as preserver of oaths and treaties...The Umbrian god ...with the combination of the two forms of the Roman god in his name performs a real service in establishing the unity of Dius Fidius and Semo Sancus as the one god Semo Sancus Dius Fidius"; D. Briquel "Sur les aspects militaires du dieu ombrien Fisus Sancius" in Melanges de l'Ecole Francais de Rome Antiquite' 1979 p.134-135: datives Ia 15 Fiso Saci, VI b 3 Fiso Sansie; vocative VI b 9, 10, 12, 14 , 15 Fisovie Sansie; accusative VI b 8 Fisovi Sansi; genitive VI b15 Fisovie Sansie; dative VI b5,6, VII a 37 Fisovi Sansi; I a 17 Fisovi.

- ↑ The major triad is composed by Iove, Marte and Vofiune, termed Grabovii; beside it there is minor one whose components are associated each with one of the Grabovii: Trebus Iovius with Iove, Fisus Sancius with Marte and Tefer Iovius with Vofiune respectively. Cf. D. Briquel above p. 136.

- ↑ D. Briquel "Sur les aspects militaires du dieu ombrien Fisus Sancius" in Melanges de l'Ecole Francais de Rome Antiquite' 1979 pp.135-137.

- ↑ D. Briquel above.

- ↑ W. W. Fowler The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic London 1899 p. 140 ; R. D. Woodard Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult Chicago 2006 p. 186 ff.

- ↑ R. D. Woodard Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult p.220 ff.; Macrobius Saturnalia III 12, 1-8

- ↑ N. T. De Grummond Etruscan Myth Sacred History and Legend 2006 p. 141; Peter F. Dorcey The Cult of Silvanus: a Study in Roman Folk Religion Brill Leyden 1992 p. 11 citing C. De Simone Etrusco Sanchuneta La Parola del Passato 39 (1984) pp. 49-53.

- ↑ Palmer p. 16 and Norden p. 215, above.

External links

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Semo Sancus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Semo Sancus". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Ancient Library article