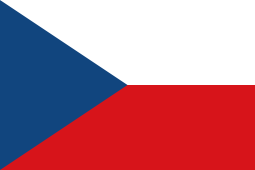

Second Czechoslovak Republic

| Czecho-Slovak Republic | ||||||||||||||||

| Česko-Slovenská republika | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Motto Pravda vítězí / Pravda víťazí "Truth prevails" | ||||||||||||||||

Anthem

| ||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) The Czechoslovak Republic in 1939. | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Prague | |||||||||||||||

| Languages | Czech Slovak | |||||||||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||||||||||||

| President | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1938 | Jan Syrový (acting) | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1938–1939 | Emil Hácha | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1938 | Jan Syrový | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1938–1939 | Rudolf Beran | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||||||||||||

| • | Upper house | Senate | ||||||||||||||

| • | Lower house | Chamber of Deputies | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | |||||||||||||||

| • | Munich Agreement | 30 September 1938 | ||||||||||||||

| • | German occupation | 15 March 1939 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1939 | 99,348 km² (38,358 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1939 est. | 10,400,000 | ||||||||||||||

| Density | 104.7 /km² (271.1 /sq mi) | |||||||||||||||

| Currency | Czechoslovak koruna | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | ||||||||||||||||

The Second Czechoslovak Republic (Czech / Slovak: Česko-Slovenská republika), sometimes also called the Czech-Slovak Republic,[1] existed for 169 days, between 30 September 1938 and 15 March 1939. It was composed of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and the autonomous regions of Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia, the latter renamed as of 22 November 1938 as Carpathian Ukraine (Karpatská Ukrajina in Czech).

The Second Republic was the result of the events following the Munich Agreement, where Czechoslovakia was forced to cede the German-populated Sudetenland region to Germany on October 1, 1938, as well as southern parts of Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia to Hungary. After the Munich Agreement and the German government making clear to foreign diplomats that Czechoslovakia was now a German client state, the Czechoslovak government attempted to curry favour with Germany by banning the country's Communist Party, suspending all Jewish teachers in German educational institutes in Czechoslovakia, and enacted a law to allow the state to take over Jewish companies.[2] In addition, the government allowed the country's banks to effectively come under German-Czechoslovak control.[2]

The Czechoslovak Republic was dissolved when Germany invaded it on 15 March 1939 and annexed the Czech region into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. On the same day as the German occupation, the President of Czechoslovakia, Emil Hácha was appointed by the German government as the State President of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia which he held throughout the war.

History

The Czechoslovak Republic had become a shell of its former self and was now a greatly weakened state. The Munich Agreement had resulted in Bohemia and Moravia losing about 38% of their combined area to Germany, with some 3.2 million German and 750,000 Czech inhabitants. Lacking its natural frontier and having lost its costly system of border fortification, the new state was militarily indefensible. Hungary received 11,882 square kilometres in southern Slovakia and southern Ruthenia; according to a 1941 census, about 86.5% of the population in this territory was Hungarian. Poland acquired the town of Těšín with the surrounding area (some 906 km², some 250,000 inhabitants, mostly Poles) and two minor border areas in northern Slovakia, more precisely in the regions Spiš and Orava. (226 km², 4,280 inhabitants, only 0.3% Poles). Moreover, the Czechoslovak government had problems in taking care of the 115,000 Czech and 30,000 German refugees, who had fled to the remaining rump of Czechoslovakia.

The political system of the country was also in chaos. Following the resignation of Edvard Beneš on October 5, General Jan Syrový had acted as President until Emil Hácha was chosen as President on November 30, 1938. Hácha was chosen because of his Catholicism and conservatism and because of not being involved in any government that led to the partition of the country. He appointed Rudolf Beran, the leader of the Agrarian Party since 1933, as prime minister on December 1, 1938. He was, unlike most Agrarians, rather rightist, and sceptical of liberalism and democracy. The Communist Party was dissolved, although its members were allowed to remain in Parliament. Tough censorship was introduced, and an Enabling Act was also introduced, which allowed the government to rule without parliament.

Ethnic tensions

The greatly weakened Czechoslovak Republic was forced to grant major concessions to the non-Czechs. Following the Munich Agreement, the Czechoslovak army transferred parts of its units, originally in the Czech lands, to Slovakia, meant to counter the obvious Hungarian attempts to revise the Slovak borders.

The Czechoslovak government accepted the Žilina Agreement stipulating the formation of an autonomous Slovak government with all Slovak parties except the Social Democrat on 6 October 1938. Jozef Tiso was nominated as its head. The only common ministries that remained were those of National Defence, Foreign Affairs and Finances. As part of the deal, the country officially adopted the short-form name of Czecho-Slovakia.

Similarly, the two major factions in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, the Russophiles and Ukrainophiles, agreed on the establishment of an autonomous government, which was constituted on 8 October 1938. Reflecting the spread of modern Ukrainian national consciousness, the pro-Ukrainian faction, led by Avhustyn Voloshyn, gained control of the local government and Subcarpathian Ruthenia was renamed Carpatho-Ukraine.

On 17 October, Ferdinand Ďurčanský, Franz Karmasin and Alexander Mach were received by Adolf Hitler. On 1 January 1939 the Slovak State Assembly was opened. On 18 January the first elections of the Slovak Assembly took place, where the Slovak People's Party received 98% of the votes. On 12 February, Vojtech Tuka and Karmazin met with Adolf Hitler, and on 22 February Tiso proposed the formation of an autonomous Slovak state during his presentation of the Slovak Government to the assembly. On February 27 the Slovak government asked the central government for the Slovakisation of the Czecho-Slovak army units stationed in Slovakia and for Slovak ambassadors and consuls to be named as representatives of the autonomous Slovak state.

Disputes continued and, on 1 March 1939, the Ministerial Committee of the Czecho-Slovak government met, where the question of Slovak departure from the state was in focus. There were some disagreement between Tiso and other Slovak politicians, and Karol Sidor (who had represented the Slovak government in the meeting) returned to Bratislava to discuss the matter with Tiso. On March 6 the Slovak government proclaimed its loyalty to the Czecho-Slovak Republic and its wish to remain a part of the state.

However, in a meeting with Hermann Göring on 7 March Ďurčanský and Tuka were pressed to declare their autonomy from the Czecho-Slovak state. After their return two days later, the Hlinka Guard was mobilised, which in turn forced the Czecho-Slovak President, Emil Hácha, to react strongly and declared martial law in Slovakia.

Division of Czechoslovakia

In January 1939, negotiations between Germany and Poland broke down. Hitler scheduled a German invasion of Bohemia and Moravia for the morning of 15 March. In the interim, he negotiated with the Slovak People's Party and with the Kingdom of Hungary and its representatives for the Hungarian minority in Slovakia to prepare the dismemberment of the Second Czechoslovak Republic before the invasion. On 13 March he invited Monsignore Jozef Tiso to Berlin, where he offered Tiso the option of proclaiming the Slovak state and seceding from Czecho-Slovakia. In such a case, Germany would be Slovakia's protector and would not allow the Hungarians to press on Slovakia any additional territorial demands. If the Slovaks declined, Germany would occupy Bohemia and Moravia and disinterest himself in Slovakia's fate—in effect, leaving the Slovaks to the mercies of the Hungarians and the Poles (Poland had claimed the Slovak Spiš territory since the Polish-Czechoslovak War). During the meeting, Joachim von Ribbentrop passed on a (false) report saying that Hungarian troops were approaching Slovak borders. Tiso refused to make such a decision himself, after which he was allowed by Hitler to organize a meeting of the Slovak parliament ("Diet of the Slovak Land"), which would approve Slovakia's independence.

On 14 March, the Slovak parliament convened and heard Tiso's report on his discussion with Hitler as well as a declaration of independence. Some of the deputies were skeptical of making such a move, but the debate was quickly quashed when Karmasin announced that any delay in declaring independence would result in Slovakia being divided between Hungary and Germany. Under these circumstances, Parliament unanimously declared Slovak independence, and Tiso was appointed the first Prime Minister of the new republic. The next day, Tiso sent a telegram (which had actually been composed the previous day in Berlin) asking the Reich to take over the protection of the newly minted state. The request was readily accepted.[3]

Meanwhile, Czechoslovak president Emil Hácha was summoned to a meeting with Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring during the early hours of 15 March, and informed Hácha of the imminent German invasion plan. Here Hácha was threatened with aerial bombardment of Prague[4] unless he signed a document accepting the capitulation of the Czechoslovak Army and the foundation of a Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia under the protection and supremacy of the German Reich. After several strokes, he was forced to sign the document even though he did not consult the parliament beforehand.

On the morning of 15 March, German troops entered Bohemia and Moravia, meeting no resistance. The Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine did encounter resistance but the Hungarian army quickly crushed it. On 16 March, Hitler went to Czechoslovakia and from Prague Castle proclaimed the new Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

Thus, independent Czechoslovakia collapsed in the wake of foreign aggression, ethnic divisions and internal tensions. Subsequently, interwar Czechoslovakia has been idealized by its proponents as the only bastion of democracy surrounded by authoritarian and fascist regimes. It has also been condemned by its detractors as an artificial, Czech-dominated and unworkable creation of intellectuals supported by the great victorious powers of the First World War, notably France and the British Empire. Interwar Czechoslovakia comprised lands and peoples that were far from being integrated into a modern nation-state. Moreover, the dominant Czechs, who had suffered political discrimination under the Habsburgs, were not able to cope with the demands of other nationalities. In fairness to the Czechs, it should be acknowledged that some of the minority demands and perceived persecution of ethnic Germans served as mere pretexts to justify intervention by Nazi Germany. Considering that Czechoslovakia was able to maintain a viable economy and a democratic political system under such circumstances was indeed a remarkable achievement during the interwar period.

Bibliography

- (Czech) Jan, Gebhart and Kuklík, Jan: Druhá republika 1938–1939. Svár demokracie a totality v politickém, společenském a kulturním životě, Paseka (2004), Praha, Litomyšl, ISBN 80-7185-626-6.

- Kennan, George F. (1968), From Prague after Munich: Diplomatic Papers, 1938–1939, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05620-X

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Czecho-Slovak Republic (1938–1939). |

- ↑ Miller, Francis. The Complete History of World War II. p. 111.

- 1 2 Crowhurst, Patrick. Hitler and Czechoslovakia in World War II: Domination and Retaliation. P83-84.

- ↑ William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

- ↑ Dokumenty z historie československé politiky 1939–1945. II., Prague 1966, p. 420–422

.svg.png)