Sartorius muscle

| Sartorius muscle | |

|---|---|

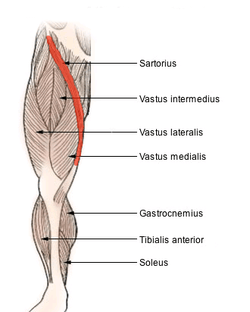

Muscles of lower thigh. (Rectus femoris removed to reveal the vastus intermedius.) | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Anterior superior iliac spine of the pelvic bone |

| Insertion | anteromedial surface of the upper tibia in the pes anserinus |

| Artery | femoral artery |

| Nerve | femoral nerve (sometimes from the intermediate cutaneous nerve of thigh) |

| Actions | Flexion, abduction, and lateral rotation of the hip, flexion of the knee[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus sartorius |

| TA | A04.7.02.016 |

| FMA | 22353 |

The sartorius muscle (/sɑːrˈtɔəri.əs/) is the longest muscle in the human body. It is a long, thin, superficial muscle that runs down the length of the thigh in the anterior compartment. Its upper portion forms the lateral border of the femoral triangle.

Structure

The sartorius muscle is the longest muscle in the body and arises by tendinous fibres from the anterior superior iliac spine, running obliquely across the upper and anterior part of the thigh in an inferomedial direction.

It descends as far as the medial side of the knee, passing behind the medial condyle of the femur to end in a tendon.

This tendon curves anteriorly to join the tendons of the gracilis and semitendinosus muscles which together form the pes anserinus, finally inserting into the proximal part of the tibia on the medial surface of its body.

Nerve supply

Situated in the anterior fascial compartment of the thigh, the sartorius is innervated via the anterior (or superficial) branch of the femoral nerve (AORN Journal, J. Murauski). The femoral nerve is responsible for both sensory and motor components in the sartorius and provides proprioceptive feedback for the muscle (Anatomy and Physiology 5th edition, K. Saladin)

Variation

Slips of origin from the outer end of the inguinal ligament, the notch of the ilium, the ilio-pectineal line or the pubis occur.

The muscle may be split into two parts, and one part may be inserted into the fascia lata, the femur, the ligament of the patella or the tendon of the semitendinosus.

The tendon of insertion may end in the fascia lata, the capsule of the knee-joint, or the fascia of the leg.

The muscle may be absent.[2]

Function

The sartorius muscle assists in flexing, weak abduction and lateral rotation of the hip, and flexion of knee.[1] Turning the foot to look at the sole demonstrates all four actions of the sartorius.

Clinical significance

One of the many conditions that can disrupt the use of the sartorius is pes anserine bursitis, an inflammatory condition of the medial portion of the knee. This condition usually occurs in athletes from overuse and is characterized by pain, swelling and tenderness. The pes anserinus is made up from the tendons of the gracilis, semitendinosus, and sartorius muscles; these tendons attach onto the anteromedial proximal tibia. When inflammation of the bursa underlying the tendons occurs they separate from the head of the tibia (eMedicine, MD. M. Glencross).

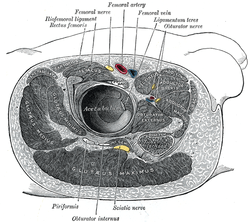

An anatomical significance of the sartorius muscle is that it forms one of the boundaries of the femoral triangle along with the inguinal ligament and the adductor longus muscle. The femoral triangle contains the femoral artery, vein and nerve.

History

Etymology

Sartorius comes from the Latin word sartor, meaning tailor,[3] and it is sometimes called the tailor's muscle.

There are four hypotheses as to the genesis of the name. One is that this name was chosen in reference to the cross-legged position in which tailors once sat. Another is that it refers to the location of the inferior portion of the muscle being the "inseam" or area of the inner thigh tailors commonly measure when fitting a pant. A third is that the muscle closely resembles a tailor's ribbon. Additionally, antique sewing machines required continuous cross body pedaling. This combination of lateral rotation and flexion of the hip and flexion of the knee gave tailors particularly enlarged sartorius muscles.

Additional images

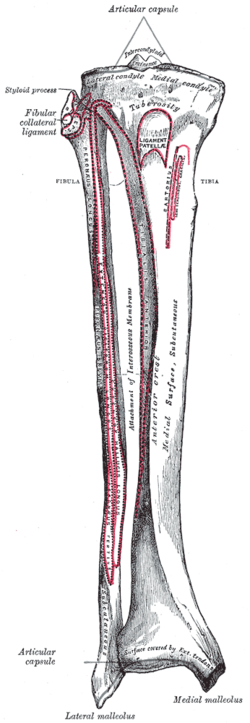

Bones of the right leg. Anterior surface.

Bones of the right leg. Anterior surface. Structures surrounding right hip-joint.

Structures surrounding right hip-joint. Muscles of the iliac and anterior femoral regions.

Muscles of the iliac and anterior femoral regions. Cross-section through the middle of the thigh.

Cross-section through the middle of the thigh. Muscles of the gluteal and posterior femoral regions.

Muscles of the gluteal and posterior femoral regions. Femoral sheath laid open to show its three compartments.

Femoral sheath laid open to show its three compartments. The left femoral triangle.

The left femoral triangle. The lumbar plexus and its branches.

The lumbar plexus and its branches. Front and medial aspect of right thigh.

Front and medial aspect of right thigh.- Sartorius muscle

- Sartorius muscle

- Sartorius muscle

- Sartorius muscle

- Sartorius muscle

- Sartorius muscle

- Sartorius muscle

- Muscles of thigh. Cross section.

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- 1 2 Moore, Keith; Anne Agur (2007). Essential Clinical Anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 334. ISBN 0-7817-6274-X.

- ↑ Scott-Conner, Carol E. H.; David L. Dawson (2003). Operative Anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 606. ISBN 0-7817-3529-7.

- ↑ Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary, Fourth Edition, Mosby-Year Book Inc., 1994, p. 1394

External links

- 208339022 at GPnotebook

- Anatomy photo:14:st-0407 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Cross section image: pembody/body15a - Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15 - Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna