San Miguel Ixtapan (archaeological site)

| Otomi Culture – Archaeological Site | ||

| San Miguel Ixtapan, Basement 3 | ||

San Miguel Ixtapan, ballgame court | ||

| Name: | San Miguel Ixtapan Archaeological Site | |

| Type | Mesoamerican archaeology | |

| Location | San Miguel Ixtapan, Tejupilco (municipality), State of Mexico | |

| Region | Mesoamerica | |

| Coordinates | 18°48′27″N 100°09′19″W / 18.80750°N 100.15528°WCoordinates: 18°48′27″N 100°09′19″W / 18.80750°N 100.15528°W | |

| Culture | Otomí – Toltec – Aztec | |

| Language | Otomí – Nahuatl | |

| Chronology | 500 to 1500 CE | |

| Period | Mesoamerican Classical, Postclassical | |

| Apogee | 750 to 900 CE | |

| INAH Web Page | San Miguel Ixtapan Archaeological Site (Spanish) | |

San Miguel Ixtapan is an archaeological site located in the municipality of Tejupilco (Nahuatl "Texopilco" or "Texopilli"), in the State of Mexico.

Tejupilco is about 100 kilometers[1] west from the city of Toluca, Mexico State, on federal highway 134. The site is some 15 kilometers south of the municipal head, on state highway 8 that leads to Amatepec.[2]

This site is one of the few explored in the southwest region of the State of Mexico, that has provided some archaeological information on an area that virtually was not explored.[2]

Its apogee was in the aftermath of the Teotihuacan decline. Located in an area which probably served as a liaison between the Central Highlands and regions of Michoacán and Guerrero, San Miguel Ixtapan had its greatest growth between 750 and 900 CE. Then the site reaches a substantial expansion and built most of the structures of the ceremonial area now visible, they represent only a portion of what was the site in its splendor. San Miguel Ixtapan was located in a privileged place with deposits of basalt prisms used for construction, fertile land and one of the larger flow springs in the State.[3]

Background

The earliest evidence of human habitation in the state is a quartz scraper and obsidian blade found in the Tlapacoya area, which was an island in the former Lake Chalco. They are dated to the Pleistocene era which dates human habitation back to 20,000 years. These first peoples were hunter-gatherers. Stone Age implements have been found all over the territory from mammoth bones, to stone tools to human remains. Most have been found in the areas of Los Reyes Acozac, Tizayuca, Tepexpan, San Francisco Mazapa, El Risco and Tequixquiac. Between 20,000 and 5000 BCE, the people here eventually went from hunting and gathering to sedimentary villages with farming and domesticated animals. The main crop was corn, and stone tools for the grinding of this grain become common. Later crops include beans, chili peppers and squash grown near established villages. Evidence of ceramics appears around 2500 BCE with the earliest artifacts of these appearing in Tlapacoya, Atoto, Malinalco, Acatzingo and Tlatilco.[4]

The earliest major city of the state is Teotihuacan, built between 100 BCE and 100 CE.[4]

Between 800 and 900 CE, the Matlatzincas established their dominion with Teotenango as capital.[4]

During Axayacatl[5] reign (1469–1481) the Aztecs and Purépecha conquered much of the Matlazincas settlements, imposing names such as: Metepec, Capulhuac Quauhpanoayan, Xochiaca Tzinacantepec, Zoquitzinco, Toluca, Xiquipilco, Tenantzinco, Teotenango and Calixtlahuaca.[4]

Other dominions during the prehispanic period include that of the Chichimecas in Tenayuca and of the Acolhuas in Huexotla, Texcotizingo and Los Melones. Other important groups were the Mazahuas in the Atlacomulco area. Their center was at Mazahuacán, next to Jocotitlán mountain. The Otomis were centered in Jilotepec.

Toponymy

The name of the place is composed from the words "Iztatl" (salt) and "pan" (place): "place where is salt",[2] this makes reference to the importance that salt exploitation had from prehispanic times, it was fundamentally due to the saltpeter (Potassium nitrate) water wells that existed near the town.[6] (Still mined, although in smaller scale)

In relation to Tejupilco, there is no certainty of the true meaning of the word Tejupilco until today, it is known that a large volcanic rock which has a human footprint in the Huarache Hill east of San Simón, gave name to the place.[7]

Texopilco, as it was known to the arrival of the Spaniards and several decades afterwards, has had several versions of its meaning: Texo (foot print), pilli (small), place of small footprint, Te (not own), xopilli (toes).[8] Place of strange footprints, or Tetl (stone), xo (foot), pilli (son or prince) Place of important people footprints.[7][9]

Interpretations have changed through the centuries, according to knowledge, feelings, views and opinions of the authors.[7]

Investigations

Initial explorations of this site occurred in 1985, it focused on the model found. The site was discovered by farmers plowing the land, when rocks and other vestiges were detected.[1]

It is difficult to determine the site constructors, although filiation from ethno historical sources indicates they were closely related to the Otomi culture.[10]

The first report of the site was given in 1958, upon discovering the so-called "model",[11] a basaltic stone where the city was carved in miniature. The stone is now under roof, under a shelter next to the Museum. It was initially thought that it was a representation of the archaeological site; however, subsequent excavations demonstrated that it is not the case and so far not found a site that matches its design; now it is considered an ideal representation of a city or a sculpted ceremonial center sculpted, taking advantage of the rock morphology.[12]

Occupations

As a result of site field investigations, at least four occupation stages were detected.[2][10]

- First Occupation. Corresponds to the last years of the Classical period (500 to 750 CE), it includes remains of a housing residential structure where Teotihuacan III and IV type figurines were discovered.[2][10]

- Second occupation. Is chronologically placed during the epiclassical period (750 to 900 CE), considered the apogee of the site, when the main structures of the place are constructed.[2][10]

- Third occupation. It is placed during the early postclassical (900 to 1200 CE), the main monuments are reused, with several architectonic modifications, additions and extensions.[2][10]

- Fourth Occupation. After 1200 CE, the site is abandoned for some time, until the time when the site is partially reoccupied by a cultural group part of the Mexica or Aztec culture; they built simple houses over the remains of older structures and remained on the site until the time Spanish invasion. One of the possible reasons why the Aztecs arrived to the area is that it is located on a strategic location, for trade control of goods from Tierra Caliente towards the central Highlands and vice versa. In addition to the saltpeter wells, previously mentioned, a product highly appreciated in prehispanic times.[2][10]

Tejupilco chronology

Documented periods of regional occupation.

12000 BCE

The oldest evidence of human occupation of these lands dates back to more than 12 thousand years, approximate date when Tejupilco cave paintings were. Early hunter-gatherers who arrived in the region at the end of the third glaciation evolved to become sedentary groups of farmers, complex societies and cultures which formed part of other civilizations.[13]

The plentiful natural resources, consequence of the rugged geography formed from millions of years ago, attracted to the Tejupilco region early settlers at least 10 thousand years ago, date in which hunter-gatherer groups created the cave paintings at the "Cueva de los Monitos"; located north of "Bejucos" at the foot of the Nanchititla Sierra. The hunter-gatherer groups have evolved to sedentary tribes through peaceful or violent exchanges with other cultures, to the domain of agriculture and domestication of animals, basic astronomical, medical and scientific knowledge.[7]

These settlements scattered throughout the region evolved, some to become complex cultures with language and religion, stratified societies and priestly classes. Others collapsed and were forgotten until the recent discovery of its ruins and study of remains that repositioned them as key parts for the study and understanding of regional history.[7]

2000 BCE

The most remote archaeological discovery is located in the archaeological area of San Miguel Ixtapan, atop of a pyramid basement, still unexplored; a mask and jade necklace were found alongside organic remains. These artifacts belong to an unknown culture that flourished in San Miguel Ixtapan, but over two thousand years before the site recorded history.[13]

Sites such as "Río Grande"[14] and the "Pararrayos de San Miguel", evidenced the collapse of the settlement from hundreds or thousands of years before the conquest of Mexico. In San Miguel Ixtapan a human body was discovered, while digging to install a lightning rod, along with prepared foods, on top of a pyramid-like basement. The body provided a chronological placement to 2000 years BCE, which means that a culture existed about 4 thousand years ago, which probably collapsed due to an invasion, next to the body finding, a necklace and green stone mask were found, these are exhibited in the San Miguel Ixtapan site Museum. In the same site are located the San Miguel Ixtapan ruins, a much later culture.[7][15]

450 CE

San Miguel Ixtapan, only archaeological site moderately excavated and studied, of the more than 180 sites existing in the region. The San Miguel Ixtapan culture flourished from 450 to 1522 CE, possibly the Chontal culture from the Balsas with close cultural and commercial ties with Teotihuacan, Tula, and the Central Highlands as well as other points of Tierra Caliente.[13]

The complex cultural overlay present in Mesoamerica throughout centuries, also existed in Tejupilco, where eventually a Chontal Kingdom was formed (Chontal meaning foreigner or not Aztec) probably Matlazinca with Tejupilco as capital and composed, according to Gaspar de Covarrubias by 18 groups[7][16]

1475 CE

The Aztecs conquered the Tejupilco kingdom.[13]

Tejupilco was conquered by the Mexicas or Aztecs around 1475-1476, during the reign of Axayacatl, consequently, at the time of the conquest the Matlazinca and Nahuatl or Mexican was spoken in the region[7][17]

Otomi Culture

The Otomi people /ˌoʊtəˈmiː/[18] is a native ethnic group inhabiting the central altiplano of Mexico. The two most populous groups are the Highland or Sierra Otomí living in the mountains of La Huasteca and the Mezquital Otomí, living in the Mezquital Valley in the eastern part of the state of Hidalgo, and in the Sierra of Querétaro state. The Otomí usually self-identify as Ñuhu or Ñuhmu depending on the dialect they speak, whereas Mezquital Otomi identify themselves as Hñähñu (pronounced [ʰɲɑ̃ʰɲũ]).[19] Smaller Otomi populations exist in the states of Puebla, Mexico, Tlaxcala, Michoacán and Guanajuato.[20] The Otomi language belonging to the Oto-Pamean branch of the Oto-Manguean language family is spoken in many different varieties some of which are not mutually intelligible. One of the early complex cultures of Mesoamerica, the Otomi were likely the original inhabitants of the central Mexican highlands before the arrival of Nahuatl speakers around ca. 1000 AD, but were gradually replaced and marginalized by Nahua peoples. In the colonial period Otomi speakers helped the Spanish conquistadors as mercenaries and allies, which allowed them to extend into territories that had previously been inhabited by semi-nomadic Chichimecs, for example Querétaro and Guanajuato.

Hence the names used by the otomíes to refer to themselves are numerous: ñätho (Toluca Valley), hñähñu (Mezquital Valley), ñäñho (Santiago de Mezquititlán, south of Querétaro) and ñ'yühü (Northern Puebla Sierra), Pahuatlán) are some of the names used by the Otomi to call themselves in their own languages, although it is common when talking in Spanish they use the Nahuatl ethnonym "Otomi".[21]

Otomí Demonym origins

As with most ethnonyms[22] used to refer to native peoples of Mexico, the "Otomi" term is not native of the referenced village. "Otomi" is a term that derives from the Nahuatl source "otómitl",[23] a word in the language of the ancient Aztecs meaning "who walks with arrows",[24] although authors such as Wigberto Jiménez Moreno have translated it as "bird hunter with arrows" (flechador de pájaros).[25] Also it is plausible that the demonym is derived from the name Oton, a leader of this people in prehispanic times. According to the members of the Otomi people the term, "Otomi" is pejorative, associated with an image derived from colonial and Nahua sources where the Otomi are presented as indolent and lazy. Therefore, for some years now, there has been a resurgence of native names usage, especially in the Mezquital Valley, Querétaro and northwest of the State of Mexico; territories with a high percentage of Otomi ethnic population. On the other hand, in eastern Michoacán, recovery of the native demonym has not had the same effort.>[26]

Otomi Language

Otomi (/ˌoʊtəˈmiː/; Spanish: Otomí Spanish pronunciation: [otoˈmi]) is an Oto-Manguean language and one of the indigenous languages of Mexico, spoken by approximately 240,000 indigenous Otomi people in the central altiplano region of Mexico.[27] The language is spoken in many different dialects, some of which are not mutually intelligible, therefore it is in effect a dialect continuum. The word Hñähñu [hɲɑ̃hɲũ1] has been proposed as an endonym, but since it represents the usage of a single dialect it has not gained wide currency. Linguists have classified the modern dialects into three dialect areas: the Northwestern dialects spoken in Querétaro, Hidalgo and Guanajuato; the Southwestern dialects spoken in the State of Mexico; and the Eastern dialects spoken in the highlands of Veracruz, Puebla, and eastern Hidalgo and in villages in Tlaxcala and Mexico states.

Like all other Oto-Manguean languages, Otomi is a tonal language and most varieties distinguish three tones. Nouns are marked only for possessor (either by prefixes or by proclitics); plural number is marked by the definite article and by a verb suffix, and some dialects maintain the historically existing dual number marking.

The site

In spite of the finding of the "model" rock in 1958, formal archaeological excavations only started in 1985, and Museum construction started in 1993.[12]

In addition to archaeological monuments, San Miguel has a Site Museum that holds and displays many pieces found on site that have been recovered during controlled excavations. This material offers to information about the culture, materials, and way of life of the ancient settlers of the region.[2][12]

Some of the figurines found in San Miguel Ixtapan indicate an occupation dating back to the formative period, between 800 and 200 BCE, they are very similar to the elaborate Tlapacoya and Tlatilco ceramic; some of them very peculiar represent pregnant women. Others clay figures are similar to those discovered in Teotihuacan phases III and IV (500 and 750 CE) and confirm a continued occupation during the classical period. Much of these objects were found in the deeper layers of the ballgame court. However, the stage of further expansion of San Miguel Ixtapan is during the mesoamerican epiclassical period (750-900 CE). Then is when the principal monuments in the site are built matching the splendor of Xochicalco, Morelos; Teotenango, South of the Valley of Toluca and Cholula, Puebla, cities that flourished after the decline of Teotihuacan.[12]

The main pieces that are exhibited in the Museum belong to the epiclassical mesoamerican period, as the anthropomorphic sculptures with crossed arms, ceramic masks with a kind of eye masking, the ballgame court (tlachmalacátl) stone ring and stone disks carved with the image of a dual serpent in the center. This period corresponds to the sculpture area, where there are two anthropomorphic Stelae carved in green stone and embedded in the ground.[12]

During this time the influence of the culture of the Balsas is stronger than ever, it can be appreciated by the large ceramics amount depicting style similarity. Some vessels are identical to those found at the Caracol dam, near Arcelia, Guerrero. The strong cultural exchange that existed between the cultures of Michoacán and Guerrero is notorious, and in the south of the State Mexico, but also the matlatzincas influence is noted.[12]

In the late postclassical period the region was occupied by Aztecs, who imposed tribute or formed army alliances against the Purépecha. Constructive activity is very poor, however this period correspond to some of the burials with lavish offerings. Shell beads, necklaces, cooper needles, earrings, obsidian "bezotes", spear points, darts and numerous vases accompanied the dead on their journey to the underworld. Many of these objects have been perfectly preserved and can be seen in various Museum showcases.[12]

In the center of town, is the Church of San Miguel Ixtapan, its constructors used carved stone blocks from the archaeological constructions, and in the atrium of the church is another block.[12]

Structures

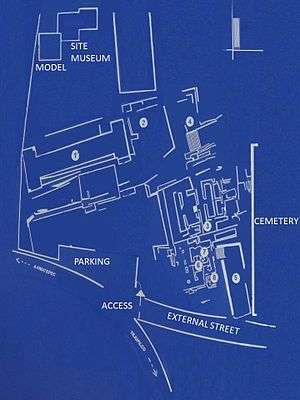

Upon entering the site, to the right side are two huge earth mounds that contain prehispanic ruins,[28] and to the left is the ballgame court.[1]

Prehispanic Scale Model

The Model [Maqueta, (Spanish)], according to archaeologists, belongs to the early postclassical (900 to 1200 CE), San Miguel Ixtapan continued to be occupied and its buildings were constantly modified.[12]

Is a three by four meter basaltic rock outgrowth, in which the ancient inhabitants of the place carved with great skills a series of architectonic elements such as: ballgame courts, platforms or foundations, stairways with sides, roofed temples, etc., depicting an exceptional scale ceremonial center. As a result of investigations of this site and neighboring areas, it has been possible to determine that this architectonic complex does not seem to make reference to any of the known sites to date. Hence, more than a "scale model", it seems a Votive offering element in which some type of rites and ceremonies were carried out.[2]

Researchers have called "The model", a rocky outcrop that depicts the architectural design of a city, but the question is: what city?[28]

May well be a city that is still lost; It can also be the drawing of a city yet to be built.[28]

Specialists are not inclined one way or another: it is the architectural model of a City, perhaps conceived at the time, it even contains several spaces (up to five[1]) in the form of ballgame courts.[28]

Ballgame Court

The ballgame court has an outline oriented on an east-west direction; it is capital letter "I" shaped or double "T", the court area measures 50 meters long by 7.50 wide. Headers at both end measure 15 by 7.8 meters. A particularity of this ballgame court consists of the fact that the land was excavated for its construction below grade, reason why access stairways were built to enter the court. Towards the south side, a platform was added (Platform1), where many human burials were found containing rich offerings, from its characteristics this is placed within the postclassical period.[2]

Basement 2

It is said to have been barely explored, due to the tree on top (see Basement 2 picture).[1]

On its eastern side, have remains of red stucco. On its western side has a recessed stairway.[1]

Basement 3

It is the most important structure on the site.[1]

The structure is composed of three superimposed bodies, with a series of rooms in its superior part, which was accessed by a stairway with intermediate inclined walls (alfardas). The second level of this monument, a complex of overlaid residential-ceremonial enclosures is located distributed on different levels, certainly as a consequence of the need to make modifications to spaces and accesses.[2]

Above the structure is a room, with stucco remains in floor and walls, which probably served for the king to rest.[28]

On the north-west corner is a small niche holding a Tlaloc sculpture, God of water, very important in this area for corn planting, other products and salt collection were the main income sources of the area.[28]

Stairway 4

On the north side of Basement 3, is a stairway leading down from the Tlaloc niche at site level, it is made from large basalt blocks, below is an external patio, surrounded by a wall. There are remains of a drainage system.[1]

Sunken Patio 5

On the south side of Basement 3 is the "Patio Hundido" (sunken patio), used hundreds of years ago to make offerings and rituals: strategically located so that attendees could focus on it, inside is a sacrificial stone.[28]

It has two access stairways, one with sides finished, leading directly to the "Sculptures Enclosure".[2][1]

Structures 6, 7 & 8

These structures are not accessible to visitors, the sunken patio and the structures are chained off.[1]

These are located south of basement 3 and west of the sunken patio, at the North West corner.[1]

The enclosures are said to contain the "Recinto de la Banqueta" and the "Recinto de las esculturas", with accesses facing east and west respectively.[1]

- Recinto de la Esculturas. Is located inside the first structure, a large amount of offerings and figurines was recovered, in addition to two sculptures made with green stone, embedded in the floor, depicting Huiztocihuatl (Goddess of salt water) & Tlaloc (Rain God).[1] This structure was called

so called because most of the figurines exhibited in the site Museum from the archaeological site, made from basalt green stone were found in this place.[28]

- Recinto de la Banqueta. It is one of the two rooms, contains stucco remains in floor and walls, which probably served for the king to rest. This place is known as "Recinto de la banqueta".[28] It also contains a kind of ceremonial walkway, displays as ornament a molding with architectonic stone nails.[2]

Many structures are covered with stucco, perhaps to protect them from destruction due to the many invasions suffered with the Aztec occupation.[28]

Site Museum

The museum was opened in 1995 by the "Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura".[28]

San Miguel has a site museum which exhibits a large amount of recovered pieces. This material provided information about the culture and way of life of the ancient inhabitants of the region.[2]

The Museum is small; however keeps a collection of more than 800 items, many in perfect state of conservation and cleverly distributed pursuant to museographer Jorge Carrandi layout. This material has been discovered, mostly as part of mortuary offerings. By ceramic type and style of the sculptures, it has been chronologically placed from the postclassical mesoamerican period.[12]

Some of the ceramic figures include women figurines, some pregnant, dating back to 800 BCE to 200 CE.[28]

Other pieces belong to the splendor period, between 750 and 900 CE. Including vessels, deities representations, feathers and the skeleton of an important man, exhibited as was found in one of the external mounds.[28]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Clément, Marianne C. (Dec 26, 2010). "Site visit". Notes & Photographs. San Miguel Ixtapan. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Rodríguez Garcia, Norma L. "Pagina web INAH, San Miguel Ixtapan" [San Miguel Ixtapan INAH Web Page]. INAH (in Spanish). Mexico. Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "San Miguel Ixtapan" (in Spanish). Mexico: Arqueologia Mexicana. Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "Historia" [History]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2005. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- ↑ Axayacatl means "Water-mask" or "Water-face") was a ruler (tlatoani) of the Postclassic Mesoamerican Aztec Empire and city of Tenochtitlán, who reigned from 1469 to 1481. He was preceded on the throne by Moctezuma I and followed by his brother Tízoc in 1481.

- ↑ "San Miguel Ixtapan". visiting Mexico (in Spanish). Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sinaí Gómez, Rodolfo (Municipal Chronicler). "Antecedentes Históricos" [Tejupilco Historical Backgropund] (in Spanish). Tejupilco Municipal Government. Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Olaguibel. Onomatología del Estado de México. En: De la Fuente José María. Hidalgo Íntimo. México. 1979. Pág. 18.

- ↑ León López Gabriel. Nido de Águilas. Pág. 53

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "San Miguel Ixtapan (Tejupilco)" (in Spanish). Mexico: State of Mexico Government. Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ A similar model carved in stone was seen in the Tiwanaku site, in Bolivia, closely resembling the actual structures at the site.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "El museo de San Miguel Ixtapan (Estado de México)". Mexico desconocido (in Spanish). Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "Historia Cronológica del Municipio de Tejupilco" [Tejupilco municipality chronologic history] (in Spanish). Tejupilco Municipal Government. Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Ruins discovered in April 2004 while searching for the ruins of the old hacienda de Río Grande.

- ↑ Osorio, Víctor. Antrophology Museum Director

- ↑ De la Fuente, José Maria. Hidalgo Íntimo. Facsimile edition, original published 1910. México 1979. Pg. 26.

- ↑ Historia Chichimeca. Pág.257. En Ibíd..Pág. 23-25.

- ↑ in Spanish spelling Otomí Spanish: [otoˈmi]

- ↑ See Wright Carr (2005).

- ↑ Lastra (2006)

- ↑ Lately some speakers of Mezquital Valley have begun to consider the word "Otomi" as derogatory. This does not occur in other variants and therefore it is used. It is also a term used widespread in the Spanish speaking world in all areas. In this regard, echoing David C. Wright (2005: 19) words: "while the word 'Otomi' has been used in texts that belittle these ancient inhabitants of central Mexico, it is considered convenient to use the same word in the works in an attempt to regain their history; instead of discarding it, I propose it should be vindicated".

- ↑ An ethnonym (from the Greek: ἔθνος, éthnos, "nation" and ὄνομα, ónoma, "name") is the name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (where the name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms or endonyms (self-designation; where the name is created and used by the ethnic group itself).

- ↑ Gomez de Silva 2001.

- ↑ Barrientos López, 2004: 6

- ↑ Jiménez Moreno, 1939.

- ↑ CIESAS, s/f a.

- ↑ INEGI, "Perfil sociodemográfico", p. 69.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Marin Ruiz, Guillermo (Dec 30, 2009). "Recuperan zona arqueológica de San Miguel Ixtapan" [Archaeological area of San Miguel Ixtapan is recuperated]. Toltecayotl (in Spanish). Tejupilco. Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

Bibliography

External links

- Encyclopedia of Mexican States. (Spanish)

- Encyclopedia of Mexican States, H. AYUNTAMIENTO DE TEJUPILCO. (Spanish)

- San Miguel Ixtapan (Tejupilco) (Spanish)