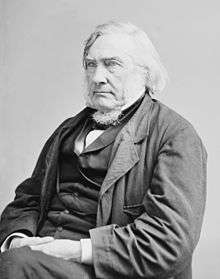

Samuel Nelson

| Samuel Nelson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

In office February 14, 1845 – November 28, 1872 | |

| Nominated by | John Tyler |

| Preceded by | Smith Thompson |

| Succeeded by | Ward Hunt |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

November 10, 1792 Hebron, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

December 13, 1873 (aged 81) Cooperstown, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

Pamela Woods (1819–1822) Catharine Russell (1825–1873) |

| Alma mater | Middlebury College |

| Religion | Episcopalianism |

Samuel Nelson (November 10, 1792 – December 13, 1873) was an American attorney and a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Early life

Nelson was born in Hebron, New York on November 10, 1792, the son of Scotch-Irish immigrants John Rodgers Nelson and Jean McArthur. Nelson’s family was upper middle class, and their income came from the family farm that Nelson grew up on. He obtained his early education in the common schools of Hebron, with an additional three years in private schooling. He then entered Middlebury College in Vermont.

Upon graduation in 1813, Nelson decided on a legal career and read law at the firm of John Savage and David Woods in Salem, New York. Two years later, Savage and Woods dissolved their practice, and Nelson moved to Madison County to enter into partnership with Woods. Nelson received his license to practice law in 1817, and entered private practice in Cortland. He developed a very successful practice, specializing in real estate and commercial law.

Career

Nelson was a presidential elector in 1820, voting for James Monroe and Daniel D. Tompkins. Nelson was Postmaster of Cortland from 1820 to 1823.

In 1821, Nelson served as a delegate to the New York Constitutional Convention, as one of the "Bucktails" faction led by Martin van Buren. Nelson argued for expansion of suffrage and for restructuring the state judiciary.

The revised constitution was adopted, and created eight new Circuit Courts. In 1823, Governor Joseph Yates appointed him Judge of the new Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, beginning Nelson's judicial career.

After eight years as a circuit court judge, Nelson was appointed to the New York Supreme Court in 1831 by Governor Enos Throop. Six years later Governor William Marcy additionally promoted him to the position of chief justice, succeeding John Savage.

He was an unsuccessful candidate for U.S. Senator in 1845.

On February 4, 1845, Nelson was nominated by President John Tyler as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, to fil the vacant seat of Smith Thompson. The unpopular Tyler had failed repeatedly to fill the Thompson vacancy, as the Whig-controlled Senate rejected his earlier nominations of John C. Spencer, Reuben Walworth, Edward King, and John M. Read.

Tyler's nomination of Nelson was a surprise, but proved to be a popular choice. Nelson was a highly respected chief justice on the New York Supreme Court, and had a reputation of staying out of partisan conflict. The Whigs found Nelson acceptable because, although he was a Democrat, he had a reputation as a careful and uncontroversial jurist. The Senate confirmed Nelson's appointment on February 14, 1845, after just ten days. Samuel Nelson was the only Supreme Court Justice to be appointed by President Tyler.

Nelson served as a Justice for 27 years, until his retirement on November 28, 1872. His tenure was generally viewed as unremarkable. During his time on the court Nelson acquired a reputation of fairness and directness. In accordance with his non-partisan stance, he wrote mostly uncontroversial opinions. Justice Nelson was a constitutionally conservative Democrat. He could also be described as a judicial minimalist, meaning he frequently took a moderate stance in cases offering a small, case-specific interpretation of the law, and placed a heavy emphasis on precedent. While Nelson was a strong supporter of the Union, he often criticized President Lincoln’s policies and did not believe that the Union could be saved in any worthwhile state through the use of force. While Justice Nelson remained relatively non-partisan, he did side frequently with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and Justice John A. Campbell. Nelson also rather frequently disagreed with Justice Benjamin Curtis. Justice Nelson remained good friends with Chief Justice Taney throughout his lifetime.

One of Justice Nelson’s most important opinions can be found in the case of Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont Bridge Company in 1855. The state of Pennsylvania sued the builders of a bridge over the Ohio River at Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), chartered by Virginia, declaring that it obstructed the passage of steamboats, interfering with interstate commerce, and was therefore a public nuisance.

The suit was litigated for six years and came before the Supreme Court three different times before Justice Nelson’s opinion ended it. The Court found that the bridge did in fact qualify as a public nuisance. Congress then enacted a law authorizing the bridge at its current height. In its final ruling, written by Nelson, the Court deferred to the legislative branch, overruling its previous decision, and declared that the bridge was not an obstruction to interstate commerce. Nelson drew this conclusion stating, "So far, therefore, as this bridge created an obstruction to the free navigation of the river, in view of the previous acts of Congress, they are to be regarded as modified by this subsequent legislation; and, although it still may be an obstruction in fact, is not so in the contemplation of law."[1]

Justice Nelson was one of the most prolific opinion writers of the Taney era, but very few of his opinions and decisions concerned the most important constitutional questions of the day: slavery and states rights. One such case in which his opinion was important was Dred Scott v. Sandford.

As a Justice of the New York Supreme Court, most of Nelson's notable decisions had been commercial issues. However, the case of Jack v. Martin (1834), which touched the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution, may have forshadowed his opinion in Dred Scott.

Mary Martin claimed that Jack "Martin", a black man in New York, was her slave in Louisiana. She filed suit for his return to Louisiana. Jack resisted, claiming that as both he and Mary Martin were currently residents of New York, he was free by New York law, which established a procedure for the recovery of fugitive slaves. The Recorder of New York City had issued a certificate for this, but also issued a writ of habeas corpus. The circuit court ruled for Ms. Martin, but the case was appealed to the New York Supreme Court. That court's ruling, written by Nelson, found that the power to legislate on the subject of the fugitive slave clause resided exclusively with Congress, and that the New York law was void.

This position was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), with Nelson's concurrence.

In Dred Scott, Nelson was originally designated to write the majority opinion. That opinion upheld the decision of the Missouri state court against Scott (in Scott v. Emerson), but on the narrow grounds of whether Scott was freed by his temporary residence in a free state. Nelson, avoiding controversy and partisanship as usual, did not address any of the other questions raised in the case, such as black citizenship and the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise.

While Justice Nelson was preparing this opinion, Justices McLean and Curtis decided to write vehement dissenting opinions. Learning this, Chief Justice Taney, supported by the other southern Justices, decided to write a majority opinion asserting the southern view on those issues: that blacks could not be citizens and the Compromise's restrictions on slavery were unconstitutional.

Despite this switch within the Court, Justice Nelson’s views did not change. On March 6, 1857, the Court ruled 7-2 that Dred Scott and his family remained slaves. Justice Nelson concurred in the decision, but he issued a separate concurring opinion explaining his different reasoning. Justice Nelson wrote that the question is one that each state is responsible in deciding for itself, "either by its Legislature or courts of justice, and hence, in respect to the case before us, to the State of Missouri – a question exclusively of Missouri law, and which, when determined by that State, it is the duty of the Federal courts to follow it. In other words, except in cases where the power is restrained by the Constitution of the United States, the law of the State is supreme over the subject of slavery within its jurisdiction."[2] Therefore, the Federal courts had no jurisdiction, and the appeal should be dismissed with no further discussion.

In a ruling as significant as Dred Scott it is important to take note of Justice Nelson's opinion. While his reasoning was different from Taney's, he still upheld the ruling that Dred Scott was a slave, even though he was a northern Democrat and a Unionist, and (it is said) that he was inclined to anti-slavery views.

Before the Civil War, Nelson worked to reach a compromise to prevent a war. In the winter of 1861 Justice Nelson joined Justice John Campbell as intermediaries between southern secessionists and President-elect Lincoln. Even after the fighting started, he tried to find a compromise. Nelson was distressed at this failure, but though he was staunchly opposed to war and criticized many of Lincoln's policies, he remained loyal to the Union.

One of Justice Nelson’s more noted opinions was issued in the Prize Cases, which arose from President Lincoln's declaration of a blockade of ports in states that had declared secession, to be enforced by the Navy. Navy patrolling ships captured blockade runners, which were seized as prizes. The owners sued for return of their ships, claiming that the blockade was illegal because the President did not have the constitutional authority to declare it.

In 1863, the Court found that the blockade was constitutional. Justice Nelson was the sole dissenter. He asserted that blockading ports and confiscating enemy property were war powers, and under international law could be exercised only after a formal declaration of war. Nelson wrote that "war cannot lawfully be commenced on the part of the United States without an act of Congress, such act is, of course, a formal notice to all the world, and equivalent to the most solemn declaration."[3] Therefore, the blockade of southern ports by President Lincoln was unconstitutional. Nelson was widely criticized for this opinion.

In addition to this, after the war Nelson urged the administration to reduce the penalties on the defeated South. Despite Nelson's loyalty to the Union, many questioned this as a result of both of these opinions.

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Nelson to serve on the joint high commission to arbitrate the Alabama Claims. During this time he took a leave of absence from the bench. Soon thereafter, Nelson became ill. He resigned from the commission in 1872, shortly before his death.

Death and burial

Samuel Nelson died in Cooperstown, New York, in 1873. He was buried at Cooperstown's Lakewood Cemetery.

Family

In 1819 Nelson married Pamela Woods, the daughter of John Woods. In 1825, after Pamela's death, he married Catharine Ann Russell. He had two children from his first marriage and six from his second. His fourth child with Catharine, Rensselaer Nelson, was the first United States District Court Judge for the District of Minnesota.

Honors

Nelson received the honorary degree of LL.D. from Geneva College in 1837 and Middlebury College in 1841. He received honorary LL.D. degrees from Columbia University and Hamilton College in 1870.

Legacy

His law office may today be seen at the Farmers' Museum in Cooperstown.[4]

Sources

- ↑ Pennsylvania v. The Wheeling and Belmont Bridge Company, 59 U.S. 421, 435 (1852).

- ↑ Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 460 (1857).

- ↑ Prize Cases, 67 of U.S. 635, 687 (1863).

- ↑ "Historic Structures - Samuel Nelson Law Office | The Farmers' Museum". Farmersmuseum.org. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- Finkelman, (1994), “Hooted History”: History, 19: 83–102. 10.1111/j.1540-5818.1994.tb00022.x Gatell, "Samuel Nelson." Court, 1789-1969: 2 (1969): 817-29.

- Hall, L., Huebner, 2nd Boston, Wadsworth, 1992. Huebner, Justices, Rulings, Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2003.

- “Jack Rendition.” http://www.nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/legal-history-eras-02/history-new-york-legal-eras-jack-martin.html Maltz, Lawrence, Kansas, 2007.

- Parrish, "Samuel Nelson." York, Garland, 1994. 337-38.

- “Pennsylvania & Company.” https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/59/421/case.html

- "The Cases." http://www.casebriefs.com/blog/law/constitutional-law/constitutional-law-keyed-to-cohen/separation-of-powers/the-prize-cases/

- “Samuel Nelson.” http://supreme-court-justices.insidegov.com/l/29/Samuel-Nelson

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samuel Nelson. |

- Samuel Nelson at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Smith Thompson |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1845–1872 |

Succeeded by Ward Hunt |

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||