Salisbury National Cemetery

|

Salisbury National Cemetery | |

|

Unknown Dead Monument with the Maine Monument in the background. | |

| |

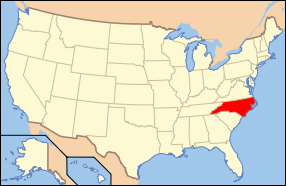

| Location | 202 Government Rd., Salisbury, North Carolina |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°39′41″N 80°28′34″W / 35.66139°N 80.47611°WCoordinates: 35°39′41″N 80°28′34″W / 35.66139°N 80.47611°W |

| Built | 1863 |

| Architectural style | Dutch Colonial Revival |

| MPS | Civil War Era National Cemeteries MPS |

| NRHP Reference # | 99000393[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 12, 1999 |

| American Civil War cemeteries |

|---|

|

|

Salisbury National Cemetery is a United States National Cemetery located in the city of Salisbury, in Rowan County, North Carolina. Its first interments were Union soldiers who died at a Confederate prisoner of war camp at the site during the American Civil War. Administered by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, it encompasses 65 acres (26 ha), 15 acres (6.1 ha) in the original location and 50 acres (20 ha) at the annex.[2] As of 2012 it had 6500 interments (in 6000 standard graves, many of which also hold a spouse), plus an estimated 3,800 in 18 mass graves, at the original location and 5000, in 4500 graves, in the new location.

History

Salisbury Prison

In May 1861, North Carolina seceded from the Union and the Confederacy sought a site in Rowan County for a military prison.[3] A twenty-year-old abandoned cotton mill near the railroad line was selected as the location. It was brick and three stories tall with an attic. Cottages and a stockade were later added. The number of prisoners increased from 120 in December 1861 to 1400 in May 1862.[4] In the early part of the war, prisoners were well cared for and even indulged in baseball; recorded in a drawing by Maj. Otto Boetticher.

By October 1864 the prison held 5000, and 10,000 soon after that. The town of Salisbury had only 2000 residents, making it the fourth largest town in the state, and there was concern about the safety of those on the outside. Later when the prison became overcrowded and the death rate rose from 2% to 28%, mass graves were used to accommodate the dead.

In February 1865 men were moved to other locations. 3729 who could do so marched to Greensboro to be taken by train to Wilmington, North Carolina. 1420 others were transferred to Richmond, Virginia. By the time Union Gen. George Stoneman reached Salisbury, the prison was a supply depot. Stoneman ordered the prison burned and a wood fence built around the graves. Of the buildings that constituted the prison, one house on Bank Street still stands.[4]

Cemetery

Salisbury National Cemetery began as simply a place for the Confederacy to inter Union prisoners of war who died while held at Salisbury Prison. The conditions at the prison were poor, and many of those incarcerated there succumbed to disease or starvation.[4] A report by General T.W. Hall stated that 10,321 prisoners arrived between October 5, 1864 and February 17, 1865, and that 2,918 died at the hospital, while 3,479 were buried.[5] Many of the dead were buried in eighteen 240-foot-long (73 m) trench graves without coffins in a former corn field, so it is unknown exactly how many prisoners were buried there.[4] 11,700 is the generally accepted number which is shown on the monument, but research has shown the number to be close to 3800.[5][6]

The fence Stoneman had ordered be built around the trenches was later replaced with a stone wall. After the American Civil War, the cemetery officially became a National Cemetery and had remains from other cemeteries around the area transferred to it.[4]

Salisbury National Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999.[1]

By 1994 the cemetery was expected to fill up by 1997, with no more burials other than spouses of those already there.[7] Despite additions in 1976, 1985 and 1995 that gave the cemetery a total of 12.5 acres, and 5800 buried at the cemetery already,[8] it was later predicted that by the end of 1999, the cemetery would have no more room. Representatives of the cemetery, veterans, and Rowan County traveled to Washington, D.C asking for help, and on Memorial Day 1999, the Veterans Administration announced the donation of about 40 acres (16 ha), at the W.G. (Bill) Hefner VA Medical Center in Salisbury.[9] The land included the Brookdale Golf Course, donated by Samuel C. Hart American Legion Post to be used by the hospital when it opened in 1953, and used until the late 1980s.[10] The expansion gave the cemetery enough room to last for 50 to 75 years, with room for 20,000 more veterans and family members. A groundbreaking ceremony was held at the cemetery annex on Pearl Harbor Day 1999.[8][9] The first burial in the new location took place in March 2000.[2]

In April 2000, 4.7 acres (1.9 ha) became part of the Salisbury National Cemetery. Two years later, a $2.8 million expansion began on 31 acres (13 ha) of the former golf course, with space to bury 12,000 more people.[10]

On November 14, 2011, work began on a new columbarium with a capacity of 1000, which was expected to last ten years. The existing columbarium was nearly filled. Also, the cemetery was adding 2400 "pre-placed in-ground crypts"; these allowed 1500 burials per acre compared to 700 with normal graves.[11]

As of Memorial Day 2012, the original cemetery, with about 7000 markers, was closed to new burials, except for spouses of those already buried. The annex had 4000 markers and was the state's only open national cemetery.[2]

Number buried in trenches

In 1869, Brevet Gen. L. Thomas estimated the number buried at 11,700 after opening two of the trenches. and that number is used on the monument to unknown soldiers; research by Louis A. Brown shows the number to be close to 3800. Mark Hughes of Kings Mountain, North Carolina has campaigned not only to get the number corrected, but to add grave markers for the 3500 whose identities can be determined from sources such as an 1868 Roll of Honor. He cites federal law requiring a marker for anyone buried in a national cemetery. As of 2014, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs does not plan to change the monument or add individual markers. The problem is that certain people "may" be buried but there is no way to be sure. In 2009, an interpretive panel was added to show what research has determined, and in 2014, the Roll of Honor was being added to a web site.[5]

Notable interments

- Red Prysock, R&B tenor saxophonist

- Earl B. Ruth, U.S. Representative and Governor of American Samoa

Notable monuments

- A 25-foot-high (7.6 m) granite monument topped by a statue of a soldier, erected in 1908 by the state of Maine

- The Federal Monument to the Unknown Dead, a 38-foot-tall (12 m) granite obelisk erected in 1875 at a cost of $10,000.[5]

- The Pennsylvania Monument, a 40-foot-high (12 m) monument on a granite base, erected in 1909

See also

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 Wineka, Mark (2012-05-28). "Keeping up the National Cemetery proves to be quite the task". Salisbury Post. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- ↑ Brown, Louis A. (1992). The Salisbury Prison: A Case Study of Confederate Military Prisons - Revised and Enlarged. Wilmington, North Carolina: Broadfoot Publishing Company.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Prison History". Salisbury Confederate Prison Association. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

- 1 2 3 4 Wineka, Mark (2014-07-04). "Exaggerated number on National Cemetery monument probably won't be corrected". Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ↑ Therese T. Sammartino (February 1999). "Salisbury National Cemetery" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved 2015-02-01.

- ↑ Timothy Ball, "National Cemetery Rejects Land," Salisbury Post, 1994-08-07.

- 1 2 Wineka, Mark (1999-11-10). "Funding OK'd to start work on cemetery". Salisbury Post. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- 1 2 Ashe, Natasha (1999-12-08). "Groundbreaking ensures room in National Cemetery for decades". Salisbury Post. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- 1 2 Post, Rose (2002-06-06). "National Cemetery set to expand again at VA". Salisbury Post. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ↑ Minn, Karissa (2011-11-12). "Construction set to begin at National Cemetery". Salisbury Post. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salisbury National Cemetery. |

- 35°41′03″N 80°29′34″W / 35.68417°N 80.49278°W – Coordinates for the Annex

- National Cemetery Administration

- Salisbury National Cemetery

- Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) No. NC-2, "Salisbury National Cemetery, 202 Government Road, Salisbury, Rowan, NC"

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Salisbury National Cemetery

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Salisbury National Cemetery Annex

- Salisbury National Cemetery at Find a Grave

- Salisbury National Cemetery Annex at Find a Grave

.jpg)