Saber-toothed cat

A saber-toothed cat (alternatively spelled sabre-toothed cat)[1] is any member of various extinct groups of predatory mammals that were characterized by long, curved saber-shaped canine teeth. The large maxillary canine teeth extended from the mouth even when it was closed. The saber-toothed cats were found worldwide from the Eocene epoch to the end of the Pleistocene epoch (42 mya – 11,000 years ago), existing for about 42 million years.[2][3][4]

One of the best known genera is Smilodon, species of which, especially S. fatalis, are popularly referred as a "saber-toothed tiger," a genus within the subfamily Machairodontinae of the carnivoran family Felidae. Extant members of Felidae include cats of the subfamilies Felinae and Pantherinae.

However, usage of the word cat is a misnomer, as most saber-toothed "cats" are not related to modern cats of Felidae: instead, many are members of other feliform carnivoran families, such as Barbourofelidae and Nimravidae;[5][6] the oxyaenid "creodont" genera Machaeroides and Apataelurus; and two lineages of metatherian mammals, the thylacosmilids of Sparassodonta, and deltatheroideans, which are more closely related to marsupials than to the placental mammals of the other orders mentioned. In this regard, saber-toothed cats can be viewed as examples of convergent evolution.[7] This convergence is remarkable due to not only to development of elongated canines, but also a suite of other characteristics, such as a wide gape and bulky forelimbs, that is so consistent that it has been termed the “saber-tooth suite.”[8]

Of the feliform lineages, the family Nimravidae is the oldest, entering the landscape around 42 mya and becoming extinct by 7.2 mya. Barbourofelidae entered around 16.9 mya and were extinct by 9 mya. These two would have shared some habitats.

Morphology

These subfamilies evolved their saber-toothed characteristics entirely independently. They are most known for having maxillary canines which extended down from the mouth even when the mouth was closed. Saber-toothed cats were generally more robust than today's cats and were quite bear-like in build. They were believed to be excellent hunters and hunted animals such as sloths, mammoths, and other large prey. Evidence from the numbers found at La Brea Tar Pits suggests that Smilodon, like modern lions, was a social carnivore.[9]

The first late saber-tooth instance is a group of animals ancestral to mammals but not yet mammals. Known as synapsids or mammal-like reptiles, they were one of the first groups of animals to experience specialization of teeth and many had long canines. Some had two pairs of upper canines with two jutting down from each side, but most had one pair of upper extreme canines. Because of their primitiveness, they are extremely easy to tell from machairodonts. With no cononoid process, many sharp "premolars" more like pegs than scissors and a very long, lizard-like head are among several characteristics that mark them out.

The second appearance is in Deltatheroida, a lineage of Cretaceous metatherians. At least one genus, Lotheridium, possess long canines, and given both the predatory habits of the clade as well as the generally incomplete material this may have been a more widspread adaptation.[10]

The third appearance of long canines is Thylacosmilus, which is the most distinctive of the saber-tooth mammals and is also easy to tell apart. It differs from machairodonts in a possessing a very prominent flange and a tooth that is triangular in cross section. The root of the canines is more prominent than in machairodonts and a true sagittal crest is absent.

The fourth instance of saber teeth is from clade Oxyaenidae. The small and slender Machaeroides bore canines that were thinner than in the average machairodont. Its muzzle was longer and narrower.

The fifth saber-tooth appearance is the ancient family of carnivores, the nimravids, and they are notoriously hard to tell apart from machairodonts. Both groups have short skulls, tall sagittal crests, and their general skull shape is very similar. Some have distinctive flanges, and some have none at all, so this confuses the matter further. Machairodonts were almost always bigger, though, and their canines were longer and more stout for the most part, but exceptions do appear.

The sixth appearance is the barbourofelids. These carnivores are very closely related to actual cats, and as such, they are hard to tell apart. The best known barbourofelid is Barbourofelis, which differs from most machairodonts by a much heavier and more stout mandible, smaller orbits, massive and almost knobby flanges, and canines that are farther back. The average machairodont had well-developed incisors, but barbourofelids were more extreme.

The seventh and last of the saber-tooth group to evolve were the machairodonts themselves.

-

1st saber-tooth instance: Synapsida, the gorgonopsid Gorgonops skull

-

2nd saber-tooth instance: Thylacosmilidae (Sparassodonta) - Thylacosmilus atrox skull

-

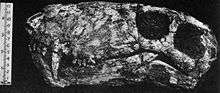

3rd saber-tooth instance: Oxyaenidae - Machaeroides skull

-

4th saber-tooth instance: Nimravidae (Carnivora) - Hoplophoneus primaevus skull and upper cervical vertebrae

-

5th saber-tooth instance: Barbourofelidae (Carnivora) - Barbourofelis skeleton

-

6th saber-tooth instance: Felidae (Carnivora) - Smilodon skull and upper cervical vertebrae

Diet

Many of the saber-toothed cats' food sources were large mammals such as elephants, rhinos, and other colossal herbivores of the era. The evolution of enlarged canines in Tertiary carnivores was a result of large mammals being the source of prey for saber-toothed cats. The development of the saber-toothed condition appears to represent a shift in function and killing behavior, rather than one in predator-prey relations. Many hypotheses exist concerning saber-tooth killing methods, some of which include attacking soft tissue such as the belly and throat, where biting deep was essential to generate killing blows. The elongated teeth also aided with strikes reaching major blood vessels in these large mammals. However, the precise functional advantage of the saber-toothed cat's bite, particularly in relation to prey size, is a mystery. A new point-to-point bite model is introduced in the article by Andersson et al., showing that for saber-tooth cats, the depth of the killing bite decreases dramatically with increasing prey size.[11] The extended gape of saber-toothed cats results in a considerable increase in bite depth when biting into prey with a radius of less than 10 cm. For the saber-tooth, this size-reversed functional advantage suggests predation on species within a similar size range to those attacked by present-day carnivorans, rather than "mega herbivores" as previously believed.

A disputing view of the cat’s hunting technique and ability is presented by C.K. Brain in “The Hunters or the Hunted?” in which he attributes the cat's prey-killing abilities to its large neck muscles rather than its jaws.[12] Large cats use both the upper and lower jaw to bite down and bring down the prey. The strong bite of the jaw is accredited to the strong temporalis muscle that attach from the skull to the coronoid process of the jaw. The larger the coronoid process, the larger the muscle that attaches there, so the stronger the bite. As C.K. Brain points out, the saber-toothed cats had a greatly reduced coronoid process and therefore a disadvantageously weak bite. The cat did, however, have an enlarged mastoid process, a muscle attachment at the base of the skull, which attaches to neck muscles. According to C.K. Brain, the saber-tooth would use a “downward thrust of the head, powered by the neck muscles” to drive the large upper canines into the prey. This technique was “more efficient than those of true cats”.[12]

Biology

The similarity in all these unrelated families involves convergent evolution of the saber-like canines as a hunting adaptation. Meehan et al.[13] note that it took around 8 million years for a new type of saber-toothed cat to fill the niche of an extinct predecessor in a similar ecological role; this has happened at least four times with different families of animals developing this adaptation. Although the adaptation of the saber-like canines made these creatures successful, it seems that the shift to obligate carnivorism, along with co-evolution with large prey animals, led the saber-toothed cats of each time period to extinction. As per Van Valkenburgh, the adaptations that made saber-toothed cats successful also made the creatures vulnerable to extinction. In her example, trends toward an increase in size, along with greater specialization, acted as a "macro-evolutionary ratchet": when large prey became scarce or extinct, these creatures would be unable to adapt to smaller prey or consume other sources of food, and would be unable to reduce their size so as to need less food.[14]

References

- ↑ See for example "sabre-toothed cat" Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 26 Oct. 2009.

- ↑ "PaleoBiology Database: ''Smilodon'', basic info". Paleodb.org. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ "PaleoBiology Database: ''Nimravidae'', basic info". Paleodb.org. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ "PaleoBiology Database: ''Barbourofelidae'', basic info". Paleodb.org. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ Barrett, Paul Z. (2016-01-01). "Taxonomic and systematic revisions to the North American Nimravidae (Mammalia, Carnivora)". PeerJ. 4: e1658. doi:10.7717/peerj.1658. PMC 4756750

. PMID 26893959.

. PMID 26893959. - ↑ Barrett, Paul Z. (2016-01-01). "Taxonomic and systematic revisions to the North American Nimravidae (Mammalia, Carnivora)". PeerJ. 4: e1658. doi:10.7717/peerj.1658. PMC 4756750

. PMID 26893959.

. PMID 26893959. - ↑ Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth (Life of the Past). Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Meachen-Samuels, Julie A. "Morphological convergence of the prey-killing arsenal of sabertooth predators". Paleobiology. 38 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1666/10036.1.

- ↑ Carbone, C.; Maddox, T.; Funston, P. J.; Mills, M. G.; Grether, G. F.; Van Valkenburgh, B. (2009). "Parallels between playbacks and Pleistocene tar seeps suggest sociality in an extinct sabretooth cat, Smilodon". Biol Lett. 5 (1): 81–85. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0526. PMC 2657756

. PMID 18957359.

. PMID 18957359. - ↑ S. Bi, X. Jin, S. Li and T. Du. 2015. A new Cretaceous metatherian mammal from Henan, China. PeerJ 3:e896

- ↑ Andersson, K.; Norman, D.; Werdelin, L. (2011). "Sabretoothed Carnivores and the Killing of Large Prey". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): 1–6. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024971. PMC 3198467

. PMID 22039403.

. PMID 22039403. - 1 2 Brain, C. K. "Part 2: Fossil Assemblages from the Sterkfontein Valley Caves: Analysis and Interpretation." The Hunters or the Hunted?: An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1981. N. pag. Print.

- ↑ Meehan, T.J.; Martin, L.D. (2003). "Extinction and Re-Evolution of Similar Adaptive Types (Ecomorphs) in Cenozoic North American Ungulates and Carnivores Reflect van der Hammen's Cycles". Naturwissenschaften. 90: 131–135. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0392-1. PMID 12649755.

- ↑ Van Valkenburgh, B. (2007). "Deja vu: the evolution of feeding morphologies in the Carnivora". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (1): 147–163. doi:10.1093/icb/icm016.

Further reading

- Mol, D., W. v. Logchem, K. v. Hooijdonk, R. Bakker. The Saber-Toothed Cat. DrukWare, Norg 2008. ISBN 978-90-78707-04-2.

- Sardella, R. "Web of Knowledge [v5.6]". SOC PALEONTOLOGICA ITALIANA, C/O E. SERPAGLI, EDITOR, IST DI PALEONTOLOGIA VIA UNIV 4, MODENA, 00000, ITALY, 10 Mar. 2012. Web. 18 Oct. 2012. <http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=WOS>.

- Anton, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253010497.

External links

- Saber-toothed Cats at the Illinois State Museum

- Sabre-toothed Cats at the UC Berkeley Museum of Paleontology

- Prehistoric cats and prehistoric cat-like creatures