SMS Habsburg (1865)

Habsburg after her modernization | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Habsburg |

| Namesake: | Habsburg |

| Builder: | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste |

| Laid down: | June 1863 |

| Launched: | 24 June 1865 |

| Commissioned: | June 1866 |

| Struck: | 22 October 1898 |

| Fate: | Scrapped, 1899–1900 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 3,588 t (3,531 long tons; 3,955 short tons) |

| Length: | 83.75 meters (274 ft 9 in) oa |

| Beam: | 15.96 m (52 ft 4 in) |

| Draft: | 7.14 m (23 ft 5 in) |

| Installed power: | 2,925 indicated horsepower (2,181 kW) |

| Propulsion: | 1 single-expansion steam engine |

| Speed: | 12.54 knots (23.22 km/h; 14.43 mph) |

| Crew: | 511 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| Notes: | [1] |

SMS Habsburg was the second and final member of the Erzherzog Ferdinand Max class of broadside ironclads built for the Austrian Navy in the 1860s. She was built by the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino; her keel was laid down in June 1863, she was launched in June 1865, and commissioning in June 1866 at the outbreak of the Third Italian War of Independence and the Austro-Prussian War, fought concurrently. The ship was armed with a main battery of sixteen 48-pounder guns, though the rifled guns originally intended, which had been ordered from Prussia, had to be replaced with old smoothbore guns until after the conflicts ended.

Habsburg saw action at the Battle of Lissa in July 1866, though she was not significantly engaged during the battle. In 1870, she was used in a show of force to try to prevent the Italian annexation of Rome while the city's protector, France, was distracted with the Franco-Prussian War, though the Italians took the city regardless. The ship's armament was revised several times in the 1870s and 1880s, before she was ultimately withdrawn from frontline service and employed as a guard ship and a barracks ship in Pola in 1886. She served in this role until 1898 when she was stricken from the naval register and broken up for scrap in 1899–1900.

Description

Habsburg was 83.75 meters (274 ft 9 in) long overall; she had a beam of 15.96 m (52 ft 4 in) and an average draft of 7.14 m (23 ft 5 in). She displaced 5,130 metric tons (5,050 long tons; 5,650 short tons). She had a crew of 511. Her propulsion system consisted of one single-expansion steam engine that drove a single screw propeller. The number and type of her coal-fired boilers have not survived. Her engine produced a top speed of 12.54 knots (23.22 km/h; 14.43 mph) from 2,925 indicated horsepower (2,181 kW).[2]

Habsburg was a broadside ironclad, and she was armed with a main battery of sixteen 48-pounder muzzle-loading smooth-bore guns. She also carried several smaller guns, including four 8-pounder guns and two 3-pounders. The ship's hull was sheathed with wrought iron armor that was 123 mm (4.8 in) thick on the battery and reduced to 87 mm (3.4 in) at the bow and stern.[2]

Service history

Habsburg was built by the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino shipyard in Trieste. Her keel was laid down in June 1863, and she was launched on 24 June 1865. The builders were forced to complete fitting-out work quickly, as tensions with neighboring Prussia and Italy erupted into the concurrent Austro-Prussian War and the Third Italian War of Independence in June 1866. Habsburg's rifled heavy guns were still on order from Krupp, and they could not be delivered due to the conflict with Prussia. Instead, the ship was armed with old smooth-bore guns.[3] Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, the commander of the Austrian Fleet, immediately began to mobilize his fleet. As the ships became fully manned, they began to conduct training exercises in Fasana.[4] On 26 June, Tegetthoff sortied with the Austrian fleet and steamed to Ancona in an attempt to draw out the Italians, but the Italian commander, Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano, refused to engage Tegetthoff.[5] Tegetthoff made another sortie on 6 July, but again could not bring the Italian fleet to battle.[6]

Battle of Lissa

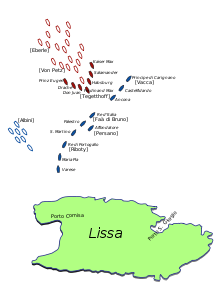

On 16 July, Persano took the Italian fleet, with twelve ironclads, out of Ancona, bound for the island of Lissa, where they arrived on the 18th. With them, they brought troop transports carrying 3,000 soldiers.[7] Persano then spent the next two days bombarding the Austrian defenses of the island and unsuccessfully attempting to force a landing.[8] Tegetthoff received a series of telegrams between the 17 and 19 July notifying him of the Italian attack, which he initially believed to be a feint to draw the Austrian fleet away from its main base at Pola and Venice. By the morning of the 19th, however, he was convinced that Lissa was in fact the Italian objective, and so he requested permission to attack.[9] As Tegetthoff's fleet arrived off Lissa on the morning of 20 July, Persano's fleet was arrayed for another landing attempt. The latter's ships were divided into three groups, with only the first two able to concentrate in time to meet the Austrians.[10] Tegetthoff had arranged his ironclad ships into a wedge-shaped formation, with Habsburg on the right flank; the wooden warships of the second and third divisions followed behind in the same formation.[11]

While he was forming up his ships, Persano transferred from his flagship, Re d'Italia, to the turret ship Affondatore. This created a gap in the Italian line, and Tegetthoff seized the opportunity to divide the Italian fleet and create a melee. He made a pass through the gap, but failed to ram any of the Italian ships, forcing him to turn around and make another attempt.[12] Habsburg was not as heavily engaged in the ensuing melee; she did not attempt to ram any Italian vessels, instead employed converging fire, though without success.[13] During this period, the leading Italian ironclads, Principe di Carignano and Castelfidardo, opened fire at long range on Habsburg, Kaiser Max, and Salamander, though they only inflicted splinter damage on Salamander.[14]

The battle ended after Tegetthoff's flagship, Erzherzog Ferdinand Max, rammed and sank Re d'Italia and heavy Austrian fire destroyed the coastal defense ship Palestro with a magazine explosion. Persano broke off the engagement, and though his ships still outnumbered the Austrians, he refused to counter-attack with his badly demoralized forces. In addition, the fleet was low on coal and ammunition. The Italian fleet began to withdraw, followed by the Austrians; Tegetthoff, having gotten the better of the action, kept his distance so as not to risk his success.[15] In the course of the battle, Habsburg had fired 170 shells and had been hit 38 times in response, though she was not damaged and sustained no casualties. The Austrian fleet proceeded to Lissa and anchored in the harbor in Saint George Bay. That evening, Habsburg, Prinz Eugen, and a pair of gunboats patrolled outside the harbor.[16]

Later career

After returning to Pola, Tegetthoff kept his fleet in the northern Adriatic, where it patrolled against a possible Italian attack. The Italian ships never came, and on 12 August, the two countries signed the Armistice of Cormons; this ended the fighting and led to the Treaty of Vienna. Though Austria had defeated Italy at Lissa and on land at the Battle of Custoza, the Austrian army was decisively defeated by Prussia at the Battle of Königgrätz. As a result of Austria's defeat, Kaiser Franz Joseph was forced to accede to Hungarian demands for greater autonomy, and the country became Austria-Hungary in the Ausgleich of 1867.[17] The two halves of the Dual Monarchy held veto power over the other, and Hungarian disinterest in naval expansion led to severely reduced budgets for the fleet.[18] In the immediate aftermath of the war, the bulk of the Austrian fleet was decommissioned and disarmed.[19]

In 1869, Kaiser Franz Joseph took a tour of the Mediterranean Sea in his imperial yacht Greif; Habsburg, Erzherzog Ferdinand Max, and a pair of paddle steamers escorted the Kaiser for the trip to Port Said at the mouth of the Suez Canal. The two ironclads remained in the Mediterranean while the other vessels passed through the Canal into the Red Sea in company with Empress Eugenie of France aboard her own yacht. The Austro-Hungarian ships eventually returned to Trieste in December.[20] The following year, Habsburg was the sole Austro-Hungarian ironclad in active service, the rest having been disarmed and laid up in Pola. Following the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War that summer and the withdrawal of the French garrison from Rome, the Italy seemed likely to annex the city from the Papal States. Franz Joseph decided to attempt to deter an Italian attack on Rome, and since Habsburg was the only capital ship available, she was sent to several Italian ports as a show of force in August. She left Italian waters in September at the same time the Prussians decisively defeated the French at the Battle of Sedan. With the collapse of the Second French Empire, and Franz Joseph unwilling to unilaterally attack Italy to defend Rome, the Austro-Hungarians backed down and Italy seized the city.[21]

In 1874 Habsburg was rearmed with a battery of fourteen 7 in (178 mm) muzzle-loading Armstrong guns and four light guns. Her battery was revised again in 1882, with the addition of four 9 cm (3.5 in) breech-loading guns, two 7 cm (2.8 in) breech-loaders, a pair of 47 mm (1.9 in) quick-firing revolver guns, and three 25 mm (0.98 in) auto-cannon. Habsburg was withdrawn from service in 1886 and thereafter served as a guard ship and barracks ship in Pola. That year, these were removed and a single 26 cm (10.2 in) gun and a 24 cm (9.4 in) gun were installed. She was stricken from the naval register on 22 October 1898 and broken up for scrap in 1899–1900.[2]

Notes

- ↑ Figures are for the ship as built.

- 1 2 3 Gardiner, p. 268

- ↑ Gardiner, pp. 266, 268

- ↑ Wilson, p. 228

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 216–218

- ↑ Wilson, p. 229

- ↑ Sondhaus, p. 1

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 221–224

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 229–230

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 223–225

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 230–231

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 232–235

- ↑ Wilson, p. 242

- ↑ Clowes, p. 360

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 238–241, 250

- ↑ Clowes, pp. 366–368

- ↑ Sondhaus, pp. 1–3

- ↑ Gardiner, p. 267

- ↑ Sondhaus, p. 8

- ↑ Sondhaus, p. 26

- ↑ Sondhaus, p. 15

References

- Clowes, W. Laird (1901). Eberle, E. W., ed. "The Naval Campaign of Lissa; Its History, Strategy and Tactics". Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. XXVII (97): 311–370. OCLC 2496995.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.