Rudolf Pfeiffer

| Rudolf Pfeiffer | |

|---|---|

| Born |

20 September 1889 Augsburg, German Empire |

| Died |

5 May 1979 (aged 89) Dachau, West Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields | Classical philology, papyrology |

| Institutions | Berlin, Hamburg, Freiburg, Munich, Oxford |

| Alma mater | Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich |

| Doctoral advisor | Franz Muncker |

| Other academic advisors | Otto Crusius and Hermann Paul |

| Doctoral students | Winfried Bühler |

Rudolf Carl Franz Otto Pfeiffer (September 20, 1889 – May 5, 1979)[1] was a German classical philologist. He is known today primarily for his landmark, two-volume edition of Callimachus and the two volumes of his History of Classical Scholarship, in addition to numerous articles and lectures related to these projects and to the fragmentary satyr plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles.

Early life and education

Pfeiffer was born in Augsburg on September 20, 1889. His parents were Carl Pfeiffer, the proprietor of a print-shop, and Elise (née Naegele).[2] The boy's grandfather Jakob, also a printer, had purchased the house of the humanist Konrad Peutinger, and Pfeiffer would later consider it a special stroke of fate that he had been born and bred in the former home of a central figure from the golden age of humanism in Augsburg.[3] He studied at the Gymnasium of the Benedictine St. Stephen's Abbey, where he was a pupil of P. Beda Grundl, a follower of Wilamowitz. Pfeiffer spent his leisure time with Beda Grundl reading Homer and a host of other Greek authors.[4]

Upon passing the Abitur in 1908, Pfeiffer moved on to Munich where he was inducted into the Stiftung Maximilianeum and began studying classical and German philology at the University of Munich.[5] There he studied under the Germanist Hermann Paul and Hellenist Otto Crusius.[2] Although Pfeiffer would continue serious study of German literature while at the university, Crusius' influence upon him was great and set the stage for his later career as a scholar of Hellenistic poetry.[4]

In 1913, under the direction of the literary historian Franz Muncker, Pfeiffer completed a dissertation on the 16th-century Augsburg Meistersinger and translator of Homer and Ovid, Johann Spreng, entitled Der Augsburger Meistersinger und Homerübersetzer Johannes Spreng, a revised version of which was published as a monograph in 1919.[6] He dedicated his dissertation as an uxori carissimae sacrum, Latin for (roughly) "a gift of devotion to a wife most dear"—namely, Lili (née Beer), a painter from Hungary whom he had married earlier in 1913.[5] In 1968 Pfeiffer would repeat this dedication in the first volume of History of Classical Scholarship, closing the preface with:

My first publication in 1914[7] bears the dedication "Uxori carissimae sacrum". I renew the words of the dedication with still deeper feeling for all that she has done for me in the course of more than half a century.[8]

Lili died the next year; the couple had no children.[2]

Academic career

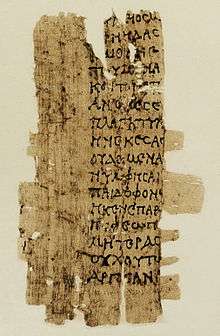

Pfeiffer later remarked that his marriage to Lili was perhaps hasty, since his prospects for an academic position were still unclear.[4] In 1912 he had taken up a position at the Universitätsbibliothek München which he would hold until 1921, but his academic career did not resume in earnest until, upon being wounded at Verdun in 1916, he decided to rededicate himself to scholarship.[4] His first passion during this period of renewed activity was the steadily accruing papyri of Callimachus, several of which he had studied in Berlin before the war with Wilhelm Schubart, the foremost literary papyrologist of the age.[4] In 1920 a promotion allowed Pfeiffer to take a year's leave and return to that city, where he made the acquaintance of Wilamowitz who recognized great potential in the young scholar and with whom Pfeiffer would have a lasting friendship.[9] The following year Pfeiffer was habilitated into the University of Munich under the chairmanship of Eduard Schwartz, the successor to his former mentor Crusius.[10] The work that earned him his Habilitation, Kallimachosstudien (1921), was soon followed by an edition of all the Callimachus papyri available at that time, entitled Callimachi fragmenta nuper reperta (1923).

Recognition of Pfeiffer's early work on Callimachus was swift, and in 1923, with Wilamowitz's endorsement, he was appointed to the professorship at Humboldt University of Berlin that had been vacated by Eduard Fraenkel when he moved on to the University of Kiel.[10] Later in the very same year Pfeiffer took over the position at Frankfurt that Karl Reinhardt had vacated at Hamburg, only to move on again in 1927 to Freiburg.[10] Finally, in 1929 he returned to his alma mater as a professor alongside Schwartz at Munich.[10]

The stability afforded by this new position allowed Pfeiffer to not only redouble his focus upon Callimachus and Greek literature in general, but also to return to a topic which had from his youth held a special interest for him: the history of humanism and classical scholarship. Over the next ten years he would publish a series of articles on this topic, his first work in this vein since revising his dissertation in 1919. Archaic epic and lyric also drew his attention during this period, as well as the new papyrus finds that were adding to the corpus of the tragedians. But Callimachus remained his primary focus, and a series of articles on the still further fragments which were being published at this time solidified his reputation as the foremost scholar of the poet's work, and in 1934 he was recognized as a full member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities.[10]

In 1937 Pfeiffer would have to move again: he was forced out of his chair at Munich because of his marriage to a Jewish woman.[11] He and Lili relocated to Oxford, where Pfeiffer gained a position in part due to the recommendation of Schwartz, who stated that Pfeiffer "towered over all the other" philologists of his generation.[12] Eduard Fraenkel had already been driven from Germany to Corpus Christi, and with the addition of Pfeiffer The Oxford Magazine declared, "Once more, Oxford gains what Nazi Germany has lost."[12] At Oxford Pfeiffer had access to the Callimachus fragments in the vast collection of Oxyrhynchus papyri and worked amicably with the great British papyrologist Edgar Lobel who had himself published valuable work on the poet. In his obiturary of Lobel, Sir Eric Gardner Turner wrote, "The partnership over Callimachus with Rudolf Pfeiffer went well on both sides, and ended in mutual affection and esteem and a notable edition of the poet."[13] That edition of fragments, the first volume of Pfeiffer's magnum opus (1949), would be followed four years later by a second volume comprising the Hymns, Epigrams and testimonia.

Pfeiffer was restored to his chair at Munich in 1951 from which he would retire in 1957.[11] The remaining years of his life following the completion of his Callimachus were devoted to his interest in the history of classical scholarship that had been kindled while still a youth in Augsburg. In the preface to History of Classical Scholarship from the Beginnings to the Hellenistic Age (1968) he reports that, "As soon as the second volume of Callimachus was published in 1953 by the Clarendon Press, I submitted to the delegates a proposal for a History of Classical Scholarship".[14] This book was followed in 1976 by a volume treating the period from 1350–1800. He had intended to publish a third volume to cover the intervening period, but his interests in Hellenistic scholarship and the high humanist period (and the urging of Fraenkel) drew him to the bookends of his history and, upon his death, only a long abandoned sketch of the volume covering Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages had been completed.[15]

Select works

Callimachus

Principal works:

- Callimachus, vol. i: Fragmenta (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1949) ISBN 978-0-19-814115-0.

- Callimachus, vol. ii: Hymni et epigrammata (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1953) ISBN 978-0-19-814116-7.

Lesser and occasional works:

- Kallimachosstudien. Untersuchungen zur Arsinoe und zu den Aitia des Kallimachos (München: Hüber, 1922).

- Callimachi fragmenta nuper reperta (Bonn: Marcus & Weber, 1923). Edition of the papyrus finds to the point of publication.

- "Arsinoe Philadelphos in der Dichtung", Antike 2 (1926) 161–74.

- "Kallimachoszitate bei Suidas", in: Stephaniskos. Festschrift für Ernst Fabricius (Freiburg im Breisgau, 1927) 40–6.

- "Ein neues Altersgedicht des Kallimachos", Hermes 63 (1928) 302–42.

- "Βερενίκης πλόκαμος", Philologus 87 (1932) 179–228.

- "Ein Epodenfragment aus dem Jambenbuche des Kallimachos", Philologus 88 (1933) 265–71.

- Die neuen διηγήσις zu Kallimachos Gedichten (München: Beck, 1934). Short monograph.

- "Zum Papyrus Mediolanensis des Kallimachos", Philologus 92 (1934) 483–85.

- "Neue Lesungen und Ergänzungen zu Kallimachos-Papyri", Philologus 93 (1938) 61–73.

- "The measurements of the Zeus at Olympia", JHS 61 (1941) 1–5.

- "Callimachus", Proceeding of the Classical Association (1941) 7-11.

- "A fragment of Parthenios' Arete", Classical Quarterly 37 (1943) 23–32.

- "The image of the Delian Apollo and Apolline ethics", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 15 (1952) 20–32.

- "Morgendämmerung", in: Thesaurismata. Festschrift für I. Kapp zum 70. Geburtstag (München: Beck, 1954) 95–104.

- "The future of studies in the field of Hellenistic poetry", Proceeding of the Classical Association 51 (1954) 43-45.

- "The future of studies in the field of Hellenistic poetry", JHS 75 (1955) 69–73.

History of classical scholarship

Principal works:

- History of Classical Scholarship: From the Beginnings to the End of the Hellenistic Age (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968) ISBN 978-0-19-814342-0.

- History of Classical Scholarship: 1300-1850 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976) ISBN 978-0-19-814364-2

Lesser and occasional works:

- "Zum 200. Gebursttag von Chr. G. Heyne", Forschungen und Fortschritte 5 (1929) 313.

- Humanitas Erasmiana (Leipzig: Teubner, 1931). Pamphlet.

- "Wilhelm von Humboldt der Humanist", Antike 12 (1936) 35–48.

- "Von den geschichtlichen Begegnungen der kritischen Philologie mit dem Humanismus. Eine Skizze", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 28 (1938) 191–209.

- "Erasmus und die Einheit der klassischen und der christlichen Renaissance", Historisches Jahrbuch 74 (1954) 175–88.

- "Conrad Peutinger und die humanistische Welt", in: H. Rinn (ed.) Augusta: 955–1955 (München, 1955) 179–86.

- "Dichter und Philologen im französischen Humanismus", Antike und Abendland 7 (1958) 73–83.

- Philologia perennis : Festrede gehalten in der öffentlichen Sitzung der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften in München am 3. Dezember 1960 (München: Beck, 1961). Published lecture.

- "Augsburger Humanisten und Philologen", Gymnasium 71 (1964) 190–204.

Tragedians

- "Die Skyrioi des Sophokles", Philologue 88 (1933) 1—15.

- "Die Niobe des Aischylos", Philologus 89 (1934) 1–18.

- Die Netzfischer des Aischylos und der Inachos des Sophokles. Zwei Satyrspiel-Funde. (München: Beck, 1938). Short monograph.

- "Ein syntaktisches Problem in den Diktyulkoi des Aischylos", in: H. Krahe (ed.) Corolla linguistica. Festschrift F. Sommer zum 80. Geburtstag (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1955) 177–80.

- Ein neues Inachos-Fragment des Sophokles (München: Beck, 1958). Short monograph.

- "Sophoclea", Wiener Studien 79 (1966) 63–66.

Other works

- Die Meistersingerschule in Augsburg und der Homercbersetzer Johannes Spreng (Duncker & Humblot: München, 1919). A revised version of his dissertation.

- "Gottheit und Individuum in der frühgriechischen Lyrik", Philologus 84 (1928) 137–52.

- "Küchenlatein", Philologus 86 (1931) 455–59.

- Die griechische Dichtung und die griechische Kultur (München: Hüber, 1932). Pamphlet.

- "Wisdom and vision in the Old Testament", Zeitschrift für Alttestimentntliche Wissenschaft 52 (1934) 93–101.

- "Hesiodisches und Homerisches", Philologus 92 (1937) 1-18.

- "Vier Sappho-Strophen auf einem ptolemäischen Ostrakon", Philologus 92 (1937) 117–25.

- "A Greek anecdote in Shakespeare's life", Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 172–74 (1939) 5–6

- "Die goldene Lampe der Athene (Odyssee XIX,34)", Studi italiani di filologia classica 27/28 (1956) 426–33.

- "Vom Schlaf der Erde und der Tiere (Alkman, fr. 58 D.)", Hermes 87 (1959) 1–6.

Honors

During his career, Pfeiffer received the following honors:[11]

- 1934 Member, Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- 1949 Fellow, British Academy

- 1953 Member, German Archaeological Institute

- 1955 Corresponding member, Austrian Academy of Sciences (made honorary member in 1972)

- 1960 Honorary Fellow, Corpus Christi College, Oxford

- 1961 Honorary Member, Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies

- 1965 Honorary doctorate, University of Vienna

- 1971 Corresponding member, Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

- 1971 Honorary doctorate, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Works cited

- Bühler, W. (1980) "Rudolf Pfeiffer †", Gnomon 52: 402–10.

- Pfeiffer, R. (1968) History of Classical Scholarship: From the Beginnings to the end of the Hellenistic Age (Oxford: Clarendon Press)

- Turner, E.G. (1983) "Edgar Lobel †", Gnomon 55: 275–80.

- Vogt, E. (2001) "Pfeiffer, Rudolf Carl Otto", in: Neue Deutsche Biographie, volume 20 (Berlin) 323–24.

Notes

- ↑ Bühler (1980) 402.

- 1 2 3 Vogt (2001) 323.

- ↑ Bühler (1980) 402–3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bühler (1980) 403.

- 1 2 Vogt (2001) 323 and Bühler (1980) 403.

- ↑ Bühler (1980) 404; Vogt (2001) 323

- ↑ This date refers to the initial private publication of his unrevised 1913 dissertation.

- ↑ Pfeiffer (1968) xi.

- ↑ Bühler (1980) 403–4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bühler (1980) 404.

- 1 2 3 Vogt (2001) 324.

- 1 2 Bühler (1980) 406.

- ↑ Turner (1983) 278.

- ↑ Pfeiffer (1968) x.

- ↑ Bühler (1980) 407.