Richard Hornsby & Sons

| Private | |

| Industry | Agricultural engineering |

| Fate | Taken over |

| Successor | Ruston & Hornsby |

| Founded | 1828 |

| Founder | Richard Hornsby |

| Defunct | 1918 |

| Headquarters | Grantham, Lincolnshire |

| Products | Engines, Traction engines |

Number of employees | 3000 |

Richard Hornsby & Sons was an engine and machinery manufacturer in Lincolnshire, England from 1828 until 1918. The company was a pioneer in the manufacture of the oil engine developed by Herbert Akroyd Stuart, which was marketed under the Hornsby-Akroyd name. The company developed an early track system for vehicles, selling the patent to Holt & Co. (predecessor to Caterpillar Inc.) in America. In 1918, Richard Hornsby & Sons became a subsidiary of the neighbouring engineering firm Rustons of Lincoln, to create Ruston & Hornsby.

Formation

The company took the name of Richard Hornsby (1790–1864), an agricultural engineer. The company was founded when Hornsby opened a blacksmith's in Grantham, Lincolnshire, in 1815 with Richard Seaman, after joining Seaman's business in 1810. The company became Richard Hornsby & Sons in 1828, when Hornsby bought out his partner's ownership, when Seaman retired.

Product range and inventions

Agricultural machinery

Richard Hornsby & Sons grew into a major manufacturer of agricultural machinery at their Spittle Gate Works. The firm went on to produce steam engines used to drive threshing machines, and other equipment such as traction engines: their portable steam engine was one of their most important products and the market leader. A farm was obtained nearby, where all their new products were tested before being produced.

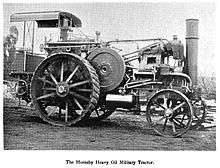

Heavy Oil Military Tractor

Following military traction engine trials in 1902, the military authorities were looking for a tractor that could do what the steam tractor achieved without its demands on fuel and water. In 1903 the military held a competition with £1000 first prize for a tractor that must weigh under 13 tons ready for the road, could haul 25 tons for 40 miles at 3 mph average speed including gradients of 1 in 18, and should be capable of 8 mph with half load and be able to climb 1 in 6 slopes towing that half load. Other conditions included winch capability of 15 tons, and ability to cross 2 feet of water. The results of the trial were reported in The Automotor Journal.[1] When the trials were held only one vehicle attended, the Hornsby Heavy Oil Tractor. Not only did it win the £1000 prize for meeting the criteria laid down, but it received a bonus of £180 for completing 58 miles towing its 25-ton load before requiring fuel or water.

Unlike the earlier single cylinder tractor made by Hornsby, this was a twin cylinder, with the cylinders at an angle to each other in a vertical plane and sharing a common crankshaft. The engine ran at 350 rpm and had a governor which operated by cutting the fuel supply in a hit and miss method, though the driver could override the governor for "spurts". The framing was of conventional steam traction engine type, with rear wheels 7 foot diameter, the front wheels 42 inches diameter. The cylinders were each 13 inch diameter and 18 inch stroke. Starting was by compressed air after pre-heating the vaporisers with bunsen torches. Sliding spur gears offered forward speeds of 1.5, 3, 5 and 8 mph, and a reverse.

Caterpillar tractor

Later, a chain-track was added to a paraffin-engined tractor. It had been developed by Hornsby's chief engineer and managing director, David Roberts: the track was patented in July 1904.[2] The following year Roberts demonstrated his tractor unofficially to the British Army's Mechanical Transport Committee, with a formal demonstration staged at Grantham in February, 1906, at which the machine outperformed a conventional wheeled tractor. A lightweight version of the tracks was also fitted to a Rochet-Schneider motor car.

In July 1907, an improved chain-track was demonstrated at the British Army's HQ at Aldershot. Roberts explained that he had plans for a trailer, also fitted with a chain-track, on which a gun could be mounted. It was at this trial that British soldiers gave the tractor the nickname "caterpillar," an expression that has stuck ever since. Roberts completed his tracked trailer and demonstrated it to the Royal Artillery in November of the same year.

There was a further demonstration at Aldershot in 1908, at which King Edward VII was present. The tractor and trailer with dummy gun in place are considered to have performed impressively, crossing various types of obstacles and ground, and the demonstration became national news. A horse team that became bogged down was easily hauled out of the mud by Roberts's machine. The Mechanical Transport Committee was amongst those that considered the system to have great potential. A newspaper suggested that this was "the germ of a land fighting unit when men will fight behind iron walls". Roberts was awarded a £1000 prize from the War Office, for his machine's performance in travelling 40 miles without stopping.[2]

A third machine was tested at Aldershot in May 1910, and towed a 60-pounder gun and its ammunition over rough ground. It was here that Major W.E. Donohue of the Mechanical Transport Committee suggested to Roberts that a single tractor unit might be fitted with a gun and bulletproof shields, thus creating some sort of self-propelled gun. Roberts did not pursue the idea, and later expressed regret at not having done so.

A further trial took place in North Wales. After contests between the No. 3 machine and horse teams, artillery officers gave a less favourable opinion of the tractor, observing that it was underpowered. An attempt was made to remedy the problem by converting it to run on petrol, a move that increased the Brake Horse Power to 105.

The Mechanical Transport Committee remained convinced of the tractor's possibilities, provided it was used in careful conjunction with horse teams. However, the Royal Artillery disagreed. The Director of Artillery, Brigadier General Stanley von Donop, emphasized the tractor's shortcomings and was unenthusiastic.

In total, 5 Hornsby caterpillar machines were made—3 oil powered engines for gun haulage; one small Schneider auto; and a steam crawler. One oil crawler survives in operational condition at The Tank Museum, Bovington, while the tracks of the steam crawler survive.

Sale of caterpillar tractor patent

By 1911, the prospects for Roberts's machine were fading. The War Office was uninterested, and refused the Mechanical Transport Committee permission to buy a Holt Tractor for evaluation, and Von Donop's opinion was the same. Roberts had spent five years on the project, barely covering his development costs with the fees received from the Army, and had secured no orders, either military or civilian. He sold the patents to the Holt Manufacturing Company in America for £4,000.[2] Learning of the Hornsby's nickname, Holt registered "Caterpillar" as a trademark in 1911. Holts later merged with C.L. Best and became The Caterpillar Tractor Company.

When the First World War broke out, Britain had to purchase caterpillar tractors from Holt to tow the Army's heavy guns, and the designers of the tank had to start from scratch, basing their ideas on imported American machines.

Roberts's chain-track played no direct part in the development of the Tank, although Lt-Col. R.E.B. Crompton, who later had an important role in its creation, had been present at some of the early trials and was influenced to some extent by the Hornsby. In the event, the first British Tanks had no sprung suspension, and the track plates were an improved version of those of another American vehicle, the Bullock tractor. Central to British Tank development was William Foster & Co., agricultural machinery manufacturers, based at Lincoln, only about 25 miles from Hornsby's.

Hornsby Akroyd Engine

Work with Herbert Akroyd Stuart in the 1890s led to the world's first commercial heavy oil engines being made in Grantham (from 8 July 1892). Other engineering companies had been offered the option of manufacturing the engine, but they saw it as a threat to their business, and so declined the offer. Only Hornsbys saw its possibilities. The first one was sold to the Newport Sanitary Authority (later to be re-bought by Hornsby and displayed in their office). In 1892, T.H. Barton at Hornsbys replaced the engine's vaporiser with a cylinder head, increased the compression ratio: the engine ran on compression alone for six hours; the first time this had been achieved. This was the first recognisable 'diesel engine', although it was built several years before Rudolf Diesel built his first prototype engines. 32,417 of the vaporising oil ('hot-bulb') engines were made by Hornsby. They would provide electricity for lighting the Taj Mahal, the Rock of Gibraltar, the Statue of Liberty (chosen after Hornsby won the oil engine prize at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893), many lighthouses, and for powering Marconi's first transatlantic radio broadcast.

First tractor

Hornsbys are credited with producing and selling the first oil-engined tractor (similar to modern-day tractors) in Britain. The Hornsby-Akroyd Patent Safety Oil Traction Engine was made in 1896 with a 20 hp engine. In 1897, it was bought by Mr. Locke-King, and this is the first recorded sale of a tractor in Britain. Also in that year, the tractor won a Silver Medal of the Royal Agricultural Society of England. That tractor would later be returned to the factory and fitted with a caterpillar track.

First commercial film

Trials featuring the Hornsby Tractor and the Rochet-Schneider were the subject of a film that was used in an attempt to promote sales and also shown in cinemas. There was also a screening in the presence of senior British officers and foreign military attachés.

Ownership

After Hornsby's death in 1864, the firm was owned by his son, also Richard. Hornby Jr died at the early age of 50, quite suddenly, in 1877. The company became a public company, being valued at £235,000. Employing about 1,400 workers, it was managed by Hornby Sr's two other sons - James and William. Throughout the First World War, Hornsbys were seconded to producing munitions and engines for the Admiralty. This left them little room for marketing or manufacturing other products - often needing years of development. The management realised their future was in doubt, so looked for a suitable company to combine with: the management chose Ruston. On 11 September 1918 when employing about 3,000 people, the company was bought out by Ruston & Proctor of Lincoln.[2]

Surviving machines

Very few of the early machines built by Richard Hornsby & Co. survive, but examples of the major types are still to be found. A working example of a Hornsby Oil tractor can be seen at some vintage vehicle shows in the UK, and another example is under restoration in Australia.

Several examples of Hornsby Ackroyd oil engines survive in preservation.[4] The Track assembly of the Hornsby Steam Tractor survives.[5]

A number of Hornsby-built steam engines and tractors are in preservation, with "The Traction Engine Register 2008" listing 12 portable engines and 3 traction engines in the UK.[6] One example – no. 1851 built in August 1871 – is in the Science Museum's store at Wroughton, with another (example no. 7297) at the Museum of Lincolnshire Life, Lincoln.

See also

- History of the internal combustion engine

- Ruston (engine builder)

- Ruston, Proctor and Company

- Marshall, Sons & Co.

- Clayton & Shuttleworth

References

- ↑ "A Triumpg for Heavy Oil", The Automotor Journal, 9 January 1904, pp36-37

- 1 2 3 4 Peter Robinson "Lincolns Excavators - The Ruston years 1875-1930," Published by Roundoak, ISBN 1-871565-42-1

- ↑ "Hornsby Chain Track Tractor (E1958.15)". Bovington Tank Museum. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ↑ Richard Hornsby & Sons oil engines

- ↑ www.hornsbycrawler.org website on crawler's preservation with photos

- ↑ The Traction Engine Register 2008, published by the SCHVPT, page 50, ISBN 978-0-946169-05-4

- Hornsby Steam Chain Tractor website

- One Hundred Years of Good Company (history of R & H), by Bernard Newman, 1957, Northumberland Press.

- Hornsby Builders Catalogue, Lincoln 1958.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hornsby vehicles. |

- Scale model of Hornsby Chain Tractor at 2005 Harrogate Model Engineering Show

- Dedication to the only commercially-sold Hornsby caterpillar crawler

- Hornsby Steam Chain Tractor website

Video clips

- 1908 promotional film (German subtitles) from the British Film Institute

- 1/3 scale Hornsby Tractor

- Scale model Hornsby Tractor at Stapleford Steam 2008 in Leicestershire

- 1905 Hornsby-Akroyd engine at the Great Dorset Steam Fair in 2005