Riboswitch

In molecular biology, a riboswitch is a regulatory segment of a messenger RNA molecule that binds a small molecule, resulting in a change in production of the proteins encoded by the mRNA.[1][2][3][4] Thus, a mRNA that contains a riboswitch is directly involved in regulating its own activity, in response to the concentrations of its effector molecule. The discovery that modern organisms use RNA to bind small molecules, and discriminate against closely related analogs, expanded the known natural capabilities of RNA beyond its ability to code for proteins, catalyze reactions, or to bind other RNA or protein macromolecules.

The original definition of the term "riboswitch" specified that they directly sense small-molecule metabolite concentrations.[5] Although this definition remains in common use, some biologists have used a broader definition that includes other cis-regulatory RNAs. However, this article will discuss only metabolite-binding riboswitches.

Most known riboswitches occur in bacteria, but functional riboswitches of one type (the TPP riboswitch) have been discovered in plants and certain fungi. TPP riboswitches have also been predicted in archaea,[6] but have not been experimentally tested.

History and discovery of riboswitches

Prior to the discovery of riboswitches, the mechanism by which some genes involved in multiple metabolic pathways were regulated remained mysterious. Accumulating evidence increasingly suggested the then-unprecedented idea that the mRNAs involved might bind metabolites directly, to affect their own regulation. These data included conserved RNA secondary structures often found in the untranslated regions (UTRs) of the relevant genes and the success of procedures to create artificial small molecule-binding RNAs called aptamers.[7][8][9][10][11] In 2002, the first comprehensive proofs of multiple classes of riboswitches were published, including protein-free binding assays, and metabolite-binding riboswitches were established as a new mechanism of gene regulation.[5][12][13][14]

Many of the earliest riboswitches to be discovered corresponded to conserved sequence "motifs" (patterns) in 5' UTRs that appeared to correspond to a structured RNA. For example, comparative analysis of upstream regions of several genes expected to be co-regulated led to the description of the S-box[15] (now the SAM-I riboswitch), the THI-box [16] (a region within the TPP riboswitch), the RFN element[17] (now the FMN riboswitch) and the B12-box[18] (a part of the cobalamin riboswitch), and in some cases experimental demonstrations that they were involved in gene regulation via an unknown mechanism. Bioinformatics has played a role in more recent discoveries, with increasing automation of the basic comparative genomics strategy. Barrick et al. (2004) [19] used BLAST to find UTRs homologous to all UTRs in Bacillus subtilis. Some of these homologous sets were inspected for conserved structure, resulting in 10 RNA-like motifs. Three of these were later experimentally confirmed as the glmS, glycine and PreQ1-I riboswitches (see below). Subsequent comparative genomics efforts using additional taxa of bacteria and improved computer algorithms have identified further riboswitches that are experimentally confirmed, as well as conserved RNA structures that are hypothesized to function as riboswitches.[20][21][22]

Mechanisms of riboswitches

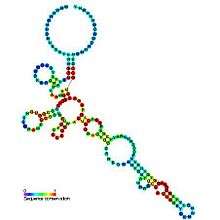

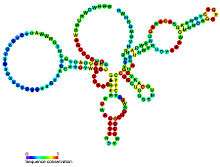

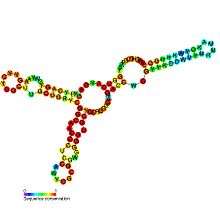

Riboswitches are often conceptually divided into two parts: an aptamer and an expression platform. The aptamer directly binds the small molecule, and the expression platform undergoes structural changes in response to the changes in the aptamer. The expression platform is what regulates gene expression.

Expression platforms typically turn off gene expression in response to the small molecule, but some turn it on. The following riboswitch mechanisms have been experimentally demonstrated.

- Riboswitch-controlled formation of rho-independent transcription termination hairpins leads to premature transcription termination.

- Riboswitch-mediated folding sequesters the ribosome-binding site, thereby inhibiting translation.

- The riboswitch is a ribozyme that cleaves itself in the presence of sufficient concentrations of its metabolite.

- Riboswitch alternate structures affect the splicing of the pre-mRNA.

- A TPP riboswitch in Neurospora crassa (a fungus) controls alternative splicing to conditionally produce an Upstream Open Reading Frame (uORF), thereby affecting the expression of downstream genes[23]

- A TPP riboswitch in plants modifies splicing and alternative 3'-end processing [24][25]

- A riboswitch in Clostridium acetobutylicum regulates an adjacent gene that is not part of the same mRNA transcript. In this regulation, the riboswitch interferes with transcription of the gene. The mechanism is uncertain but may be caused by clashes between two RNA polymerase units as they simultaneously transcribe the same DNA.[26]

- A riboswitch in Listeria monocytogenes regulates the expression of its downstream gene. However, riboswitch transcripts subsequently modulate the expression of a gene located elsewhere in the genome.[27] This trans regulation occurs via base-pairing to the mRNA of the distal gene.

Types of riboswitches

The following is a list of experimentally validated riboswitches, organized by ligand.

- Cobalamin riboswitch (also B12-element), which binds either adenosylcobalamin (the coenzyme form of vitamin B12) or aquocobalamin to regulate cobalamin biosynthesis and transport of cobalamin and similar metabolites, and other genes.

- cyclic AMP-GMP riboswitches bind the signaling molecule cyclic AMP-GMP. These riboswitches are structurally related to cyclic di-GMP-I riboswitches]] (see also "cyclic di-GMP" below).

- cyclic di-AMP riboswitches (also called ydaO/yuaA) bind the signaling molecule cyclic di-AMP.

- cyclic di-GMP riboswitches bind the signaling molecule cyclic di-GMP in order to regulate a variety of genes controlled by this second messenger. Two classes of cyclic di-GMP riboswitches are known: cyclic di-GMP-I riboswitches and cyclic di-GMP-II riboswitches. These classes do not appear to be structurally related.

- fluoride riboswitches sense fluoride ions, and function in surviving high levels of fluoride.

- FMN riboswitch (also RFN-element) binds flavin mononucleotide (FMN) to regulate riboflavin biosynthesis and transport.

- glmS riboswitch, which is a ribozyme that cleaves itself when there is a sufficient concentration of glucosamine-6-phosphate.

- Glutamine riboswitches bind glutamine to regulate genes involved in glutamine and nitrogen metabolism, as well as short peptides of unknown function. Two classes of glutamine riboswitches are known: the glnA RNA motif and Downstream-peptide motif. These classes are believed to be structurally related (see discussions in those articles).

- Glycine riboswitch binds glycine to regulate glycine metabolism genes, including the use of glycine as an energy source. Previous to 2012, this riboswitch was thought to be the only that exhibits cooperative binding, as it contains contiguous dual aptamers. Though no longer shown to be cooperative, the cause of dual aptamers still remains ambiguous.[28]

- Lysine riboswitch (also L-box) binds lysine to regulate lysine biosynthesis, catabolism and transport.

- manganese riboswitches bind manganese ions.

- NiCo riboswitches bind the metal ions nickel and cobalt.

- PreQ1 riboswitches bind pre-queuosine1, to regulate genes involved in the synthesis or transport of this precursor to queuosine. Three entirely distinct classes of PreQ1 riboswitches are known: PreQ1-I riboswitches, PreQ1-II riboswitches and PreQ1-III riboswitches. The binding domain of PreQ1-I riboswitches are unusually small among naturally occurring riboswitches. PreQ1-II riboswitches, which are only found in certain species in the genera Streptococcus and Lactococcus, have a completely different structure, and are larger, as are PreQ1-III riboswitches.

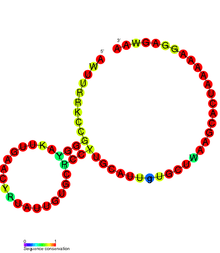

- Purine riboswitches binds purines to regulate purine metabolism and transport. Different forms of the purine riboswitch bind guanine (a form originally known as the G-box) or adenine. The specificity for either guanine or adenine depends completely upon Watson-Crick interactions with a single pyrimidine in the riboswitch at position Y74. In the guanine riboswitch this residue is always a cytosine (i.e. C74), in the adenine residue it is always a uracil (i.e. U74). Homologous types of purine riboswitches bind deoxyguanosine, but have more significant differences than a single nucleotide mutation.

- SAH riboswitches bind S-adenosylhomocysteine to regulate genes involved in recycling this metabolite that is produced when S-adenosylmethionine is used in methylation reactions.

- SAM riboswitches bind S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to regulate methionine and SAM biosynthesis and transport. Three distinct SAM riboswitches are known: SAM-I (originally called S-box), SAM-II and the SMK box riboswitch. SAM-I is widespread in bacteria, but SAM-II is found only in alpha-, beta- and a few gamma-proteobacteria. The SMK box riboswitch is found only in the order Lactobacillales. These three varieties of riboswitch have no obvious similarities in terms of sequence or structure. A fourth variety, SAM-IV riboswitches, appears to have a similar ligand-binding core to that of SAM-I riboswitches, but in the context of a distinct scaffold.

- SAM-SAH riboswitches bind both SAM and SAH with similar affinities. Since they are always found in a position to regulate genes encoding methionine adenosyltransferase, it was proposed that only their binding to SAM is physiologically relevant.

- Tetrahydrofolate riboswitches bind tetrahydrofolate to regulate synthesis and transport genes.

- TPP riboswitches (also THI-box) binds thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP) to regulate thiamin biosynthesis and transport, as well as transport of similar metabolites. It is the only riboswitch found so far in eukaryotes.[29]

- ZMP/ZTP riboswitches sense ZMP and ZTP, which are by-products of de novo purine metabolism when levels of 10-Formyltetrahydrofolate are low.

Presumed riboswitches:

- Moco RNA motif is presumed to bind molybdenum cofactor, to regulate genes involved in biosynthesis and transport of this coenzyme, as well as enzymes that use it or its derivatives as a cofactor.

Candidate metabolite-binding riboswitches have been identified using bioinformatics, and have moderately complex secondary structures and several highly conserved nucleotide positions, as these features are typical of riboswitches that must specifically bind a small molecule. Riboswitch candidates are also consistently located in the 5' UTRs of protein-coding genes, and these genes are suggestive of metabolite binding, as these are also features of most known riboswitches. Hypothesized riboswitch candidates highly consistent with the preceding criteria are as follows: crcB RNA Motif, manA RNA motif, pfl RNA motif, ydaO/yuaA leader, yjdF RNA motif, ykkC-yxkD leader (and related ykkC-III RNA motif) and the yybP-ykoY leader. The functions of these hypothetical riboswitches remain unknown.

Riboswitches and the RNA World hypothesis

Riboswitches demonstrate that naturally occurring RNA can bind small molecules specifically, a capability that many previously believed was the domain of proteins or artificially constructed RNAs called aptamers. The existence of riboswitches in all domains of life therefore adds some support to the RNA world hypothesis, which holds that life originally existed using only RNA, and proteins came later; this hypothesis requires that all critical functions performed by proteins (including small molecule binding) could be performed by RNA. It has been suggested that some riboswitches might represent ancient regulatory systems, or even remnants of RNA-world ribozymes whose bindings domains are conserved.[13][20][30]

Riboswitches as antibiotic targets

Riboswitches could be a target for novel antibiotics. Indeed, some antibiotics whose mechanism of action was unknown for decades have been shown to operate by targeting riboswitches.[31] For example, when the antibiotic pyrithiamine enters the cell, it is metabolized into pyrithiamine pyrophosphate. Pyrithiamine pyrophosphate has been shown to bind and activate the TPP riboswitch, causing the cell to cease the synthesis and import of TPP. Because pyrithiamine pyrophosphate does not substitute for TPP as a coenzyme, the cell dies.

Engineered riboswitches

Since riboswitches are an effective method of controlling gene expression in natural organisms, there has been interest in engineering artificial riboswitches [32][33][34] for industrial and medical applications such as gene therapy.[35][36]

Further reading

- Ferré-D'Amaré, Adrian R.; Winkler, Wade C. (2011). "Chapter 5. The Roles of Metal Ions in Regulation by Riboswitches". In Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel and Roland K. O. Sigel. Structural and catalytic roles of metal ions in RNA. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 9. Cambridge, U.K.: RSC Publishing. pp. 141–173. doi:10.1039/9781849732512-00141.

References

- ↑ Nudler E, Mironov AS (2004). "The riboswitch control of bacterial metabolism". Trends Biochem Sci. 29 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.004. PMID 14729327.

- ↑ Tucker BJ, Breaker RR (2005). "Riboswitches as versatile gene control elements". Curr Opin Struct Biol. 15 (3): 342–8. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.003. PMID 15919195.

- ↑ Vitreschak AG, Rodionov DA, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS (2004). "Riboswitches: the oldest mechanism for the regulation of gene expression?". Trends Genet. 20 (1): 44–50. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.008. PMID 14698618.

- ↑ Batey RT (2006). "Structures of regulatory elements in mRNAs". Curr Opin Struct Biol. 16 (3): 299–306. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.001. PMID 16707260.

- 1 2 Nahvi A, Sudarsan N, Ebert MS, Zou X, Brown KL, Breaker RR (2002). "Genetic control by a metabolite binding mRNA". Chem Biol. 9 (9): 1043–1049. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(02)00224-7. PMID 12323379.

- ↑ Sudarsan N, Barrick JE, Breaker RR (2003). "Metabolite-binding RNA domains are present in the genes of eukaryotes". RNA. 9 (6): 644–7. doi:10.1261/rna.5090103. PMC 1370431

. PMID 12756322.

. PMID 12756322. - ↑ Nou X, Kadner RJ (June 2000). "Adenosylcobalamin inhibits ribosome binding to btuB RNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (13): 7190–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.130013897. PMC 16521

. PMID 10852957.

. PMID 10852957. - ↑ Gelfand MS, Mironov AA, Jomantas J, Kozlov YI, Perumov DA (November 1999). "A conserved RNA structure element involved in the regulation of bacterial riboflavin synthesis genes". Trends Genet. 15 (11): 439–42. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01856-9. PMID 10529804.

- ↑ Miranda-Ríos J, Navarro M, Soberón M (August 2001). "A conserved RNA structure (thi box) is involved in regulation of thiamin biosynthetic gene expression in bacteria". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (17): 9736–41. doi:10.1073/pnas.161168098. PMC 55522

. PMID 11470904.

. PMID 11470904. - ↑ Stormo GD, Ji Y (August 2001). "Do mRNAs act as direct sensors of small molecules to control their expression?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (17): 9465–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.181334498. PMC 55472

. PMID 11504932.

. PMID 11504932. - ↑ Gold L, Brown D, He Y, Shtatland T, Singer BS, Wu Y (January 1997). "From oligonucleotide shapes to genomic SELEX: Novel biological regulatory loops". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (1): 59–64. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.1.59. PMC 19236

. PMID 8990161.

. PMID 8990161. - ↑ Mironov AS, Gusarov I, Rafikov R, Lopez LE, Shatalin K, Kreneva RA, Perumov DA, Nudler E (2002). "Sensing small molecules by nascent RNA: a mechanism to control transcription in bacteria". Cell. 111 (5): 747–56. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01134-0. PMID 12464185.

- 1 2 Winkler W, Nahvi A, Breaker RR (2002). "Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression". Nature. 419 (6910): 952–956. doi:10.1038/nature01145. PMID 12410317.

- ↑ Winkler WC, Cohen-Chalamish S, Breaker RR (2002). "An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding FMN". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 99 (25): 15908–13. doi:10.1073/pnas.212628899. PMC 138538

. PMID 12456892.

. PMID 12456892. - ↑ Grundy FJ, Henkin TM (1998). "The S box regulon: a new global transcription termination control system for methionine and cysteine biosynthesis genes in gram-positive bacteria". Mol Microbiol. 30 (4): 737–49. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01105.x. PMID 10094622.

- ↑ Miranda-Ríos J, Navarro M, Soberón M (2001). "A conserved RNA structure (thi box) is involved in regulation of thiamin biosynthetic gene expression in bacteria". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98 (17): 9736–41. doi:10.1073/pnas.161168098. PMC 55522

. PMID 11470904.

. PMID 11470904. - ↑ Gelfand MS, Mironov AA, Jomantas J, Kozlov YI, Perumov DA (1999). "A conserved RNA structure element involved in the regulation of bacterial riboflavin synthesis genes". Trends Genet. 15 (11): 439–42. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01856-9. PMID 10529804.

- ↑ Franklund CV, Kadner RJ (June 1997). "Multiple transcribed elements control expression of the Escherichia coli btuB gene". J. Bacteriol. 179 (12): 4039–42. PMC 179215

. PMID 9190822.

. PMID 9190822. - ↑ Barrick JE, Corbino KA, Winkler WC, Nahvi A, Mandal M, Collins J, Lee M, Roth A, Sudarsan N, Jona I, Wickiser JK, Breaker RR (2004). "New RNA motifs suggest an expanded scope for riboswitches in bacterial genetic control". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101 (17): 6421–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308014101. PMC 404060

. PMID 15096624.

. PMID 15096624. - 1 2 Corbino KA, Barrick JE, Lim J, Welz R, Tucker BJ, Puskarz I, Mandal M, Rudnick ND, Breaker RR (2005). "Evidence for a second class of S-adenosylmethionine riboswitches and other regulatory RNA motifs in alpha-proteobacteria". Genome Biol. 6 (8): R70. doi:10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-r70. PMC 1273637

. PMID 16086852.

. PMID 16086852. - ↑ Weinberg Z, Barrick JE, Yao Z, Roth A, Kim JN, Gore J, Wang JX, Lee ER, Block KF, Sudarsan N, Neph S, Tompa M, Ruzzo WL, Breaker RR (2007). "Identification of 22 candidate structured RNAs in bacteria using the CMfinder comparative genomics pipeline". Nucleic Acids Res. 35 (14): 4809–19. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm487. PMC 1950547

. PMID 17621584.

. PMID 17621584. - ↑ Weinberg Z, Wang JX, Bogue J, et al. (March 2010). "Comparative genomics reveals 104 candidate structured RNAs from bacteria, archaea, and their metagenomes". Genome Biol. 11 (3): R31. doi:10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r31. PMC 2864571

. PMID 20230605.

. PMID 20230605. - ↑ Cheah MT, Wachter A, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR (2007). "Control of alternative RNA splicing and gene expression by eukaryotic riboswitches". Nature. 447 (7143): 497–500. doi:10.1038/nature05769. PMID 17468745.

- ↑ Wachter A, Tunc-Ozdemir M, Grove BC, Green PJ, Shintani DK, Breaker RR (2007). "Riboswitch Control of Gene Expression in Plants by Splicing and Alternative 3′ End Processing of mRNAs". Plant Cell. 19 (11): 3437–50. doi:10.1105/tpc.107.053645. PMC 2174889

. PMID 17993623.

. PMID 17993623. - ↑ Bocobza S, Adato A, Mandel T, Shapira M, Nudler E, Aharoni A (2007). "Riboswitch-dependent gene regulation and its evolution in the plant kingdom". Genes Dev. 21 (22): 2874–9. doi:10.1101/gad.443907. PMC 2049190

. PMID 18006684.

. PMID 18006684. - ↑ André G, Even S, Putzer H, et al. (October 2008). "S-box and T-box riboswitches and antisense RNA control a sulfur metabolic operon of Clostridium acetobutylicum". Nucleic Acids Res. 36 (18): 5955–69. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn601. PMC 2566862

. PMID 18812398.

. PMID 18812398. - ↑ Loh E, Dussurget O, Gripenland J, et al. (November 2009). "A trans-acting riboswitch controls expression of the virulence regulator PrfA in Listeria monocytogenes". Cell. 139 (4): 770–9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.046. PMID 19914169.

- ↑ Sherman, E. M.; Esquiaqui, J.; Elsayed, G.; Ye, J.-D. (25 January 2012). "An energetically beneficial leader-linker interaction abolishes ligand-binding cooperativity in glycine riboswitches". RNA. 18 (3): 496–507. doi:10.1261/rna.031286.111.

- ↑ Switching the light on plant riboswitches. Samuel Bocobza and Asaph Aharoni Trends in Plant Science Volume 13, Issue 10, October 2008, Pages 526-533 doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2008.07.004 PMID 18778966

- ↑ Cochrane JC, Strobel SA (April 2008). "Riboswitch effectors as protein enzyme cofactors". RNA. 14 (6): 993–1002. doi:10.1261/rna.908408. PMC 2390802

. PMID 18430893.

. PMID 18430893. - ↑ Blount KF, Breaker RR (2006). "Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets". Nat Biotechnol. 24 (12): 1558–64. doi:10.1038/nbt1268. PMID 17160062.

- ↑ Bauer G, Suess B (June 2006). "Engineered riboswitches as novel tools in molecular biology". Journal of biotechnology. 124 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.12.006. PMID 16442180.

- ↑ Dixon N, Duncan, J.N., et al. (January 2010). "Reengineering orthogonally selective riboswitches". PNAS. 107 (7): 2830–2835. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911209107. PMC 2840279

. PMID 20133756.

. PMID 20133756. - ↑ Verhounig A, Karcher D, Bock R (April 2010). "Inducible gene expression from the plastid genome by a synthetic riboswitch". PNAS. 107 (14): 6204–6209. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914423107. PMC 2852001

. PMID 20308585.

. PMID 20308585. - ↑ Ketzer, P; Kaufmann, JK; Engelhardt, S; Bossow, S; von Kalle, C; Hartig, JS; Ungerechts, G; Nettelbeck, DM (4 February 2014). "Artificial riboswitches for gene expression and replication control of DNA and RNA viruses.". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (5): E554–62. doi:10.1073/pnas.1318563111. PMID 24449891.

- ↑ Strobel, B; Klauser, B; Hartig, JS; Lamla, T; Gantner, F; Kreuz, S (3 July 2015). "Riboswitch-mediated Attenuation of Transgene Cytotoxicity Increases Adeno-associated Virus Vector Yields in HEK-293 Cells.". Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 23: 1582–91. doi:10.1038/mt.2015.123. PMID 26137851.