Rugii

The Rugii, also Rugians, Rygir, Ulmerugi, or Holmrygir (Norwegian: Rugiere, German: Rugier) were an East Germanic tribe who migrated from southwest Norway to Pomerania around 100 AD, and from there to the Danube River valley. They were allies of Attila until his death in 453, and settled in what is now Austria after the defeat of the Huns at Nedao in 453.

Etymology

The tribal name "Rugii" or "Rygir" is a derivate of the Old Norse term for rye, rugr, and is thus translated "rye eaters" or "rye farmers".[1] Holmrygir and Ulmerugi are both translated as "island Rugii".[1]

Uncertain and disputed is the association of the Rugii with the name of the isle of Rügen and the tribe of the Rugini. Though some scholars suggested that the Rugii passed their name to the isle of Rügen in modern Northeast Germany, other scholars presented alternative hypotheses of Rügen's etymology associating the name to the mediaeval Rani (Rujani) tribe.[1][2]

The Rugini were only mentioned once, in a list of Germanic tribes still to be Christianised drawn up by the English monk Bede (Beda venerabilis) in his Historia ecclesiastica of the early 8th century.[1][3] Whether the Rugini were remnants of the Rugii is speculative.[1] Despite the identification by Bede as Germanic, some scholars have attempted to link the Rugini with the Rani.[3][4]

History

Origins

The Rugii had possibly migrated from southwest Norway to Pomerania in the 1st century AD.[5] Rogaland or Rygjafylke is a region (fylke) in south west Norway. Rogaland translates "Land of the Rygir" (Rugii), the transition of rygir to roga is sufficiently explained with the general linguistic transitions of the Norse language.[1] Scholars suggest a migration either of Rogaland Rugii to the southern Baltic coast, the other way around, or an original homeland on the islands of Denmark in between these two regions.[1] None of these theories is so far backed by archaeological evidence.[1] Another theory suggests that the name of one of the two groups was adapted by the other one later without any significant migration taking place.[1] Scholars regard it as very unlikely that the name was invented twice.[1]

In Pomerania

The Rugii were first mentioned by Tacitus[6] in the late 1st century.[1][7][2] Tacitus' description of their contemporary settlement area, adjacent to the Goths at the "ocean", is generally seen as the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, the later Pomerania.[1][7][2] Tacitus characterized the Rugii as well as the neighboring Goths and Lemovii saying they carried round shields and short swords, and obeyed their regular authority.[1][7][2] Ptolemaeus[8] in 150 AD mentions a place named Rhougion (also transliterated from Greek as Rougion, Rugion, Latinized Rugium or Rugia) and a tribe named Routikleioi in the same area, both names have been associated with the Rugii.[1][2] Jordanes[9] says the Goths upon their arrival in this area expelled the Ulmerugi.[1][2] and makes other, retrospect references to the Rugii in his Getica[10] of the 6th century.[1] The 9th-century Old English Widsith, a compilation of earlier oral traditions, mentions the tribe of the Holmrycum without localizing it.[1] Holmrygir are mentioned in an Old Norse Skaldic poem, Hákonarmál,[11] and probably also in the Haraldskvæði.[1]

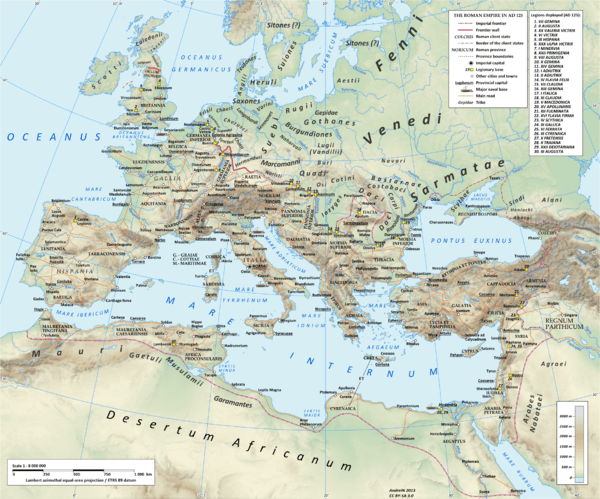

Around the mid 2nd century AD, there was a significant migration by Germanic tribes of Scandinavian origin (Rugii, Goths, Gepidae, Vandals, Burgundians, and others)[12] towards the south-east, creating turmoil along the entire Roman frontier.[13][12][14][15] These migrations culminated in the Marcomannic Wars, which resulted in widespread destruction and the first invasion of Italy in the Roman Empire period.[15] Many Rugii had left the Baltic coast during the migration period. It is assumed that Burgundians, Goths and Gepids with parts of the Rugians left Pomerania during the late Roman Age, and that during the migration period, remnants of Rugians, Vistula Veneti, Vidivarii and other, Germanic tribes remained and formed units that were later Slavicized.[16] The Vidivarii themselves are described by Jordanes in his Getica as a melting pot of tribes who in the mid-6th century lived at the lower Vistula.[17][18] Though differing from the earlier Willenberg culture, some traditions were continued.[18] One hypothesis, based on the sudden appearance of large amounts of Roman solidi and migrations of other groups after the breakdown of the Hun empire in 453, suggest a partial re-migration of earlier emigrants to their former northern homelands.[18]

The Oxhöft culture is associated with parts of the Rugii and Lemovii.[2] The archaeological Gustow group of Western Pomerania is also associated with the Rugii.[19][20] The remains of the Rugii west of the Vidivarii, together with other Gothic, Veneti, and Gepid groups, are believed to be identical with the archaeological Debczyn group.[16]

In Pannonia, Rugiland and Italy

In the beginning of the 4th century, large parts of the Rugii moved southwards and settled at the upper Tisza in ancient Pannonia, in what is now modern Hungary. They were later attacked by the Huns but took part in Attila's campaigns in 451, but at his death they rebelled and created under Flaccitheus a kingdom of their own in Rugiland, a region presently part of lower Austria (ancient Noricum), north of the Danube.[21] After Flaccitheus's death, the Rugii of Rugiland were led by king Feletheus, also called Feva, and his wife Gisa.[21] Yet other Rugii had already become foederati of Odoacer, who was to become the first Germanic king of Italy.[21] By 482 the Rugii had converted to Arianism.[5] Feletheus' Rugii were utterly defeated by Odoacar in 487; many came into captivity and were carried to Italy, and subsequently, Rugiland was settled by the Lombards.[21] Records of this era are made by Procopius,[22] Jordanes and others.[1]

Two years later, Rugii joined the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great when he invaded Italy in 489. Within the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy, they kept their own administrators and avoided intermarriage with the Goths.[5] They disappeared after Totila's defeat in the Gothic War (535-554).[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Johannes Hoops, Herbert Jankuhn, Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, 2nd edition, Walter de Gruyter, 2004, pp.452ff, ISBN 3-11-017733-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 J. B. Rives on Tacitus, Germania, Oxford University Press, 1999, p.311, ISBN 0-19-815050-4

- 1 2 David Fraesdorff, Der barbarische Norden: Vorstellungen und Fremdheitskategorien bei Rimbert, Thietmar von Merseburg, Adam von Bremen und Helmold von Bosau, Akademie Verlag, 2005, p.55, ISBN 3-05-004114-5

- ↑ Joachim Herrmann, Welt der Slawen: Geschichte, Gesellschaft, Kultur, C.H. Beck, 1986, p.265, ISBN 3-406-31162-8

- 1 2 3 4 "Rugi (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ Tacitus, Germania, Germania.XLIV

- 1 2 3 The Works of Tacitus: The Oxford Translation, Revised, With Notes, BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008, p.836, ISBN 0-559-47335-4

- ↑ Ptolemaeus II,11,12

- ↑ Jordanes, Getica, IV,26

- ↑ Jordanes, Getica, L,261.266; LIV,277

- ↑ Skj, B I,57

- 1 2 "History of Europe: The Germans and Huns". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Ancient Rome: The barbarian invasions". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Germanic peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- 1 2 "Germany: Ancient History". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- 1 2 Johannes Hoops, Hans-Peter Naumann, Franziska Lanter, Oliver Szokody, Heinrich Beck, Rudolf Simek, Sebastian Brather, Detlev Ellmers, Kurt Schier, Ulrike Sprenger, Else Ebel, Klaus Düwel, Wilhelm Heizmann, Heiko Uecker, Jürgen Udolph, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Walter de Gruyter, p.282, ISBN 3-11-017535-5

- ↑ Andrew H. Merrills, History and Geography in Late Antiquity, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p.325, ISBN 0-521-84601-3

- 1 2 3 Mayke De Jong, Frans Theuws, Carine van Rhijn, Topographies of Power in the Early Middle Ages, BRILL, 2001, p.524, ISBN 90-04-11734-2

- ↑ Magdalena Ma̜czyńska, Tadeusz Grabarczyk, Die spätrömische Kaiserzeit und die frühe Völkerwanderungszeit in Mittel- und Osteuropa, Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Łódź, 2000, p.127, ISBN 83-7171-392-4

- ↑ Horst Keiling, Archäologische Funde von der frührömischen Kaiserzeit bis zum Mittelalter aus den mecklenburgischen Bezirken, Museum für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Schwerin, 1984, pp.8:12

- 1 2 3 4 William Dudley Foulke, Edward Peters, History of the Lombards, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1974, pp.31ff, ISBN 0-8122-1079-4

- ↑ Procopius, Bellum Gothicum VI,14,24; VII,2,1.4

![]() This article contains content from the Owl Edition of Nordisk familjebok, a Swedish encyclopedia published between 1904 and 1926, now in the public domain.

This article contains content from the Owl Edition of Nordisk familjebok, a Swedish encyclopedia published between 1904 and 1926, now in the public domain.