Refugee camp

A refugee camp is a temporary settlement built to receive refugees and people in refugee-like situations. Refugee camps usually accommodate displaced persons who have fled their home country, but there are also camps for internally displaced persons. Usually refugees seek asylum after they've escaped war in their home countries, but some camps also house environmental- and economic migrants. Camps with over a hundred thousand people are common, but as of 2012 the average-sized camp housed around 11,400.[1] They are usually built and run by a government, the United Nations, international organizations (such as the International Committee of the Red Cross), or NGOs. There are also unofficial refugee camps, like Idomeni in Greece or the Calais jungle in France, where refugees are largely left without support of governments or international organizations.[2]

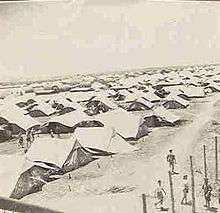

Refugee camps generally develop in an impromptu fashion with the aim of meeting basic human needs for only a short time. Facilities that make a camp look or feel more permanent are often prohibited by host country governments. If the return of refugees is prevented (often by civil war), a humanitarian crisis can result or continue.

According to UNHCR, the majority of refugees worldwide do not live in refugee camps. At the end of 2015, some 67 per cent of refugees around the world lived in individual, private accommodations.[3] This can be partly explained by the high number of Syrian refugees renting apartments in urban agglomerations across the Middle East. Worldwide, slightly over a quarter (25.4%) of refugees was reported to be living in planned/managed camps. At the end of 2015, about 56 per cent of the total refugee population in rural locations resided in a planned/managed camp, compared with 2 per cent who resided in individual accommodation. In urban locations, the overwhelming majority (99 per cent) of refugees lived in individual accommodations, compared with less than 1 per cent who lived in a planned/managed camp. A small percentage of refugees also live in collective centers, transit camps and in self-settled camps.[4]

In spite of the fact that 74 percent of refugees are in urban areas, the service delivery model of international humanitarian aid agencies remains focused on the establishment and operation of refugee camps.[5]

Facilities

The average camp size is recommended by the UNHCR to be 45 sqm per person of accessible camp area. Within this area the following facilities can usually be found:[6][7]

- An administrative headquarters to coordinate services (this may be outside the actual camp).

- Sleeping accommodations are frequently tents, prefabricated huts, or dwellings constructed of locally available materials. The UNHCR recommends a minimum of 3.5 sqm of covered living area per person. There should be at least 2m between shelters.

- Gardens attached to the family plot. The UNHCR recommends a plot size of 15 sqm per person.

- Hygiene facilities, such as washing areas, latrines or toilets. UNHCR recommends one shower per 50 persons and one communal latrine per 20 persons. Distance for the latter should be no more than 50m from shelter and not closer than 6m. Hygiene facilities should be separated by gender.

- Places for water collection: either water tanks where water is off-loaded from trucks (then filtered and potentially treated with disinfectant chemicals such as chlorine), or water tap stands that are connected to boreholes. UNHCR recommends 20 litres of water per person and one tap stand per 80 persons that should be no farther than 200m away from households.

- Clinics, hospitals and immunization centres: UNHCR recommends one health centre per 20,000 persons and one referral hospital per 200,000 persons.

- Food distribution and therapeutic feeding centres: UNHCR recommends one food distribution centre per 5,000 persons and one feeding centre per 20,000 persons.

- Communication equipment (e.g. radio). Some long-standing camps have their own radio stations.

- Security, including protection from banditry (e.g. barriers and security checkpoints) and peacekeeping troops to prevent armed violence. Police stations may be outside the actual camp.

- Schools and training centers: UNHCR recommends one school per 5,000 persons.

- Markets and shops: UNHCR recommends one market place per 20,000 persons.

Schools and markets may be prohibited by the host country government in order to discourage refugees from settling permanently in camps. Many refugee camps also have:

- Cemeteries or crematoria

- Locations for solid waste disposal. One 100 litre rubbish container should be provided per 50 persons and one refuse pit per 500 persons.

- Reception or transit centre where refugees initially arrive and register before they are allowed into the camp. Reception centres are usually far away from the camps and closer to the border of the country where refugees come from.

- Churches or other religious centers or places of worship[8]

In order to understand and monitor an emergency over a period of time, the development and organisation of the camps can be tracked by satellite[9] and analyzed via GIS.[10][11]

Arrival

Most new arrivals travel distances of up to 500 km by foot. The journey can be very dangerous, e.g. wild animals, armed bandits or militias, landmines. Some refugees are supported by IOM, some use smugglers. A large part of the new arrivals usually suffer from acute malnutrition and dehydration. There can be long queues outside the reception centres and waiting times of up to two months are possible. People outside the camp are not entitled to official support (but refugees from inside may support them). Some locals sell water or food for excessive prices and make large profits with it. It is not uncommon that some die whilst waiting outside the reception centre. They stay in the reception centre until their refugee status is approved and the degree of vulnerability assessed. This usually takes two weeks. They are then taken, usually by bus, to the camp. New arrivals are registered, fingerprinted and interviewed by the host country government and the UNHCR. Health and nutrition screenings follow. Those who are extremely malnourished will be taken to therapeutic feeding centres and the sick to hospital. Men and women receive counselling separate from each other to determine their needs. After registration they are given food rations (until that only biscuits), receive ration cards (the primary marker of refugee status), soap, jerry cans, kitchen sets, sleeping mats, plastic tarpaulins to build shelters (some get tents). Leaders from the refugee community may provide further support to the new arrivals.

Housing and sanitation

Residential plots are allocated (e.g. 10m x12 m for a family of 4 to 7 people). Shelters may sometimes be built by refugees themselves with locally available materials, but aid agencies may supply materials or even prefabricated housing.[12] Shelters are frequently very close to each other, and many families frequently share a single dwelling, rendering privacy for couples nonexistent. Camps may have communal unisex pit latrines shared by many households, but aid agencies may provide improved sanitation facilities.[13] Household pit latrines may be built by families themselves. Latrines may not always be kept sufficiently clean and disease-free. In some areas there is limited space for new pits. Each refugee is supposed to receive around 20 liters of water a day. However, many have to survive on much less than that (some may get as little as 8 litres per day).[14] There may be a high number of persons per usable tap stand (against a standard number of one per 80 persons). Drainage of water from bathroom and kitchen use may be poor and garbage may be disposed in a haphazard fashion. There may be few or no sanitary facilities accessible for people with disabilities. Poor sanitation may lead to outbreaks of infectious disease, and rainy season flooding of latrine pits increases the risk of infection.[15]

Food rations

The World Food Programme (WFP) provides food rations twice a month: 2,100 calories/person/day. Ideally it should be:

- 9 oz. (255 g) whole grain (maize or sorghum)

- 7 oz. (198 g) milled grain (wheat flour)

- 1.5 tablespoons vegetable oil

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 3 tablespoons pulses (beans or lentils)

Diet is insensitive to cultural differences and household needs. WFP is frequently unable to provide all of these staples, thus calories are distributed through whatever commodity is available, e.g. only maize flour. Up to 80 or 90% of the refugees sell part or most of their food ration to get cash. Loss of the ration card means no entitlement to food. In 2015 the WFP introduced electronic vouchers.

Economy, work and income

Research found that if enough aid is provided, the refugees' stimulus effects can boost the host countries economy.[16] The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has a policy of helping refugees work and be productive, using their existing skills to meet their own needs and needs of the host country, to:

- "Ensure the right of refugees to access work and other livelihood opportunities as they are available for nationals... Match programme interventions with corresponding levels of livelihood capacity (existing livelihood assets such as skills and past work experience) and needs identified in the refugee population, and the demands of the market... Assist refugees in becoming self-reliant. Cash / food / rental assistance delivered through humanitarian agencies should be short-term and conditional and gradually lead to self-reliance activities as part of longer-term development... Convene internal and external stakeholders around the results of livelihood assessments to jointly identify livelihood support opportunities."[17]

However, refugee hosting countries do not usually follow this policy and instead do not allow refugees to work legally. In many countries the only option is either to work for a small incentive (with NGOs based in the camp) or to work illegally with no rights and often bad conditions. In some camps it is accepted that refugees set up their own businesses. Some refugees even became rich with that. Those without a job or without relatives and friends who send remittances, need to sell parts of their food rations to get cash. As support does not usually provide cash effective demand may not be created[18]

The main markets of bigger camps usually offer electronics, groceries, hardware, medicine, food, clothing, and cosmetics, and services such as prepared food (restaurants, coffee–tea shops), laundry, internet and computer access, banking, electronic repairs and maintenance, and education. Some traders specialize in buying food rations from refugees in small quantities and selling them in large quantities to merchants outside the camp. Many refugees buy in small quantities because they don’t have enough money to buy normal sizes, i.e. the goods are put in smaller packages and sold for a higher price.

Camp structure

According to UNHCR vocabulary a refugee camp consists of: settlements, sectors, blocks, communities and families. 16 families make up a community, 16 communities make up a block, four blocks make up a sector and four sectors are called a settlement. A large camp may consist of several settlements.[7] Each block elects a community leader to represent the block. Settlements and markets in bigger camps are often arranged according to nationalities, ethnicities, tribes and clans of their inhabitants, such as at Dadaab and Kakuma.

Democracy and justice

Elected refugee community leaders are contact point within the community, for both community members and aid agencies. They mediate and negotiate to resolve problems, and liaise with refugees, UNHCR and other NGOs. Refugees are expected to convey their concerns, messages or reports of crimes, etc. through their community leaders and are therefore considered to be part of the disciplinary machinery. Many refugees mistrust them and there are allegations of aid agencies bribing them. Community leaders can decide what a crime is and thus whether it is reported to Police or other agencies and they can potentially use their position to marginalize those refugees from minority clans.[19] Refugees have been allowed to establish their own 'court' system which is funded by charities. Elected community leaders and the elders of the communities provide an informal kind of jurisdiction in refugee camps. They preside over these courts and are allowed to pocket the fines they impose. Refugees are left without legal remedies against abuses and can’t appeal against their own ‘courts’.

Security

Security of a refugee camp is usually the responsibility of the host country and is provided by the military or local police. The UNHCR only provides legal protection. However, local police or the legal system of the camp-hosting countries are not usually responsible or also not willing to get involved in things that happen inside the camps. In many camps refugees create their own patrolling systems as police protection is insufficient. Most camps are enclosed with barbed wire fence. This is not only for the protection of the refugees, but also to avoid that refugees move freely or interact with the local people.

Refugee camps may sometimes serve as headquarters for the recruitment, support and training of guerilla organizations engaged in fighting in the refugees' area of origin; such organizations often use humanitarian aid to supply their troops.[20] Rwandan refugee camps in Zaire[21] and Cambodian refugee camps in Thailand[22] supported armed groups until their destruction by local military forces.

Refugee camps are also places where terror attacks, bombings, militia attacks, stabbings and shootings take place and abductions of aid workers are not unheard of. The police can also play a role in attacks on refugees.

Health and health care

Due to crowding and lack of infrastructure, some refugee camps can become unhygienic, leading to a high incidence of infectious diseases, including epidemics. Some refugees avoid the hospital because of traditional myths about modern medicine. Outreach workers make visits from tent to tent in order to offer medical assistance to any ill and malnourished refugees. Vulnerable persons who have difficulties accessing services are supported through individual case management and home. Common illnesses are malaria, cholera, jaundice, hepatitis, measles, meningitis and malnutrition.

Freedom of movement

Once admitted to a camp, refugees usually do not have freedom to move about the country but are required to obtain Movement Passes from the UNHCR and the host country government. Yet informally many refugees are mobile and travel between cities and the camps, or otherwise making use of networks or technology in maintaining these links. Due to widespread corruption in public service there is a grey area that creates space for refugees to manoeuvre. Many refugees in the camps, given the opportunity, try to make their way to cities. Some refugee elites even rotate between the camp and the city, or rotate periods in the camp with periods elsewhere in the country in family networks, sometimes with another relative in a Western country that contributes financially. Refugee camps may serve as a safety net for people who go to cities or who attempt to return to their countries of origin. Some refugees marry nationals so that they can bypass the police rules regarding movements out of the camps. It is a lucrative side-business for many police officers working the area around the camps to have many unofficial roadblocks and to target refugees travelling outside the camps who must pay bribes to avoid deportation.

Duration and durable solutions

Although camps are intended to be a temporary solution, some of them exist for decades. Some Palestinian refugee camps have existed since 1948, camps for Eritreans in Sudan (such as the Shagarab camp) have existed since 1968,[23] the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria have existed since 1975, camps for Burmese in Thailand (such as the Mae La refugee camp) have existed since 1986, Buduburam in Ghana since 1990, or Dadaab and Kakuma in Kenya since 1991 and 1992, respectively. In fact “protracted refugee situations now account for the vast majority of the world’s refugee population”.[24] The average time a refugee stays in a camp is 17 years.[5] The longer a camp exist the lower tends to be the annual international funding and the bigger the implications for human rights.[25] Some camps grow into permanent settlements and even merge with nearby older communities, such as Ain al-Hilweh, Lebanon and Deir al-Balah, Palestine.

People may stay in these camps, receiving emergency food and medical aid, for many years and possibly even for their whole life. To prevent this the UNHCR promotes three alternatives to that:

- Once it is safe for them to return to their home countries the refugees can use voluntary return programmes.[26]

- In some cases, refugees may be integrated and naturalised by the country they fled to.[27]

- In some cases, often after several years, refugees may get the offer to be resettled in "third countries". Globally, about 17 countries (Australia, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States) regularly accept "quota refugees" from refugee camps.[28] The UNHCR works in partnership with these countries and resettlement programmes, such as the Gateway Protection Programme,[29] that support refugees after arrival in the new countries. In recent years, most quota refugees have come from Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Liberia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and the former Yugoslavia which have been disrupted by wars and revolutions.

Notable refugee camps

Africa

- There are 12 camps in the east of Chad, such as Breidjing Camp. They are hosting approximately 250,000 Sudanese refugees from the Darfur region in Sudan and were opened in 2002. The other camps are Oure Cassoni, Mile, Treguine, Iridimi, Touloum, Kounoungou, Goz Amer, Farchana, Am Nabak, Gaga and Djabal.[30] Some of these camps appear in the documentary Google Darfur.

- A number of camps in the south of Chad - such as Dosseye, Kobitey, Mbitoye, Danamadja, Sido, Doyaba and Djako - are hosting approximately 113,000 refugees from Central African Republic.[31]

- There are a number of camps in Uganda, such as Nakivale, Kayaka II, Kyangwali and Rwamwanja. They host 170,000 refugees from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic Of Congo.[32]

- There are four camps in Maban County in South Sudan hosting Sudanese refugees. Yusuf Batil camp is home to 37,000 refugees, Doro camp to 44,000, Jamam camp hosts 20,000 refugees and Gendrassa camp 10,000.[33]

- Buduburam refugee camp in Ghana, home to more than 12,000 Liberians[34] (opened 1990)

- Dadaab refugee camps (Ifo, Ifo II, Dagahaley, Hagadera, and Kambioos) in North Eastern Kenya, established in 1991 and now hosting more than 330,000 refugees from Somalia.[35] It is the world's largest refugee camp.[36] If taken separately, Hagadera, Dagahaley, Ifo II and Ifo were (in this order) the world's four largest camps in 2013.[37]

- Sahrawi refugee camps near Tindouf, South Western Algeria, were opened circa 1976 and are called Laayoune, Smara, Awserd, February 27, Rabouni, Daira of Bojador and Dakhla.

- Ras Ajdir camp, close to the Tunisian border in Libya, was opened in 2011 and is housing between 20,000 and 30,000 Libyan refugees.[38]

- Dzaleka camp in the Dowa District of Malawi is home to 17,000 refugees from Burundi, the DRC and Rwanda.[39]

- Nyarugusu refugee camp in Tanzania opened in 1997 and initially hosted 60.000 refugees from the DRC. Due to the recent conflicts in Burundi it also hosts 90.000 refugees from Burundi. In 2014 it was the 9th largest refugee camp.[40] However, since the conflict in Burundi it is considered one of the world's biggest and most overcrowded camps.[41]

- Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya was opened in 1991. In 2014, it was the third largest refugee camp worldwide.[36][40] As of June 2015, Kakuma hosts 185,000 people, mostly migrants from the civil war in South Sudan.[42]

- Bwagiriza and Gatumba refugee camps in Burundi host refugees from the DRC.

- There are a number of camps close to Dolo Odo in southern Ethiopia, hosting refugees from Somalia.[43] In 2014 the Dolo Odo camps (Melkadida, Bokolmanyo, Buramino, Kobe Camp, Fugnido, Hilaweyn and Adiharush) were considered to be the second largest.[36][40]

- Jomvu, Hatimy and Swaleh Nguru camps near Mombasa, Kenya, were closed in 1997. Refugees, mainly displaced people from Somalia, were either forced to relocate to Kakuma, repatriated or remunerated to voluntarily relocate into unsafe areas in Somalia.[44] Other closed camps in the area include Liboi, Oda, Walda, Thika, Utange and Marafa.

- Hart Sheik in Ethiopia hosted more than 250,000 mostly refugees from Somalia between 1988 and 2004.

- Itang camp in Ethiopia hosted 182,000 refugees from South Sudan and was the world's largest refugee camp for some time during the 1990s.[45]

- Benaco and Ngara in Tanzania.

- Kala, Meheba and Mwange camps in the northwest of Zambia host refugees from Angola and DRC.[46]

- There are 12 camps, such as Shagarab and Wad Sharifey, in eastern Sudan. They host around 66,000 mostly Eritrean refugees, the first of whom arrived in 1968.[23]

- Ali Addeh (or Ali Adde) and Holhol camps in Djibouti host 23,000 refugees, who are mainly from Somalia, but also Ethiopians and Eritreans.[47]

- Osire camp in central Namibia was established in 1992 to accommodate refugees from Angola, Burundi, the DRC, Rwanda and Somalia. It had 20,000 inhabitants in 1998 and only 3,000 in 2014.

- Lainé and Kouankan (I & II) camps in Guinea hosted nearly 29,300 refugees mostly from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Côte d'Ivoire. The number reduced to 15,000 in 2009.[48]

- Cameroon hosted more than 240,000 UNHCR registered refugees in 2014, mainly from the Central African Republic: Minawao refugee camp in the north and Gado Badzere, Borgop, Ngam, Timangolo, Mbilé and Lolo refugee camps in the east of Cameroon.[49]

- There are a number of camps in Rwanda that host 85,000 refugees from the DRC: Gihembe, Kigeme, Kiziba, Mugombwa and Nyabiheke camps.[50]

- Mentao camp in Burkina Faso hosts 13,000 Malian refugees.[51]

- PTP camp near Zwedru, Bahn camp and Little Wlebo camp in eastern Liberia is home to 12,000 refugees from Ivory Coast.[52]

- M’Bera camp in southeastern Mauritania hosts 50,000 Malian refugees.[53]

- Choucha camp in Tunisia hosted nearly 20,000 refugees from 13 different countries who fled from Libya in 2011. Half of them are sub-Saharan African and Arab refugees and the other half are Bangladeshis who had been working in Libya. 3,000 refugees remained the camp in 2012, 1,300 in 2013 and its closure is planned.[54]

- Comè in Benin hosted Togolese refugees until it was closed in 2006.

- Lazaret in Niger was the largest camp in the Sahel during the extreme drought of 1973-1975 and mainly hosted Tuareg people.

- Tongogara camp in Zimbabwe was established for Mozambican refugees in 1984 and housed in 58,000 of them in 1994.[55]

Asia

- There were a number of camps on the Thai-Cambodian border in Thailand which hosted Khmer people and Vietnamese between 1979 and 1993 (see Indochina refugee crisis and Cambodian humanitarian crisis), such as Nong Samet, Nong Chan, Sa Kaeo, Site Two, and Khao-I-Dang. There were also camps in the Thai-Laotian border region, hosting Hmong people and Laotians, such as Ban Vinai and Nong Khai.

- Whitehead Camp, Hong Kong, considered the "world's largest prison" in the early 1990s[56]

- Philippine Refugee Processing Center for Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian refugees fleeing wars in Indochina.

- There are a number of camps, such as Puzhal, for Sri Lankan Tamils, established in Tamil Nadu in India in 1983, with over 110,000 refugees by 1998.[57]

- Niatak and Torbat-e Jam camps in Iran host Afghan refugees.

- There are a number of camps in Pakistan that host Afghan refugees, such as Panian, Nasir Bagh, Old Shamshatoo, Old Akora, Gamkol, Barakai, Badaber, Girdi Jungle, Azakhel and Saranan.[58] Jelazee camp, which also hosted Afghan refugees was closed in 2001, because of security concerns.

- Champtala is a camp in Afghanistan and hosts Afghan refugees who returned from Pakistan.

- There are a number of camps in Nepal, such as the 3 Beldangi refugee camps, Goldhap, Khudunabari, Sanischare and Timai hosting Bhutanese refugees. They are Lhotshampas who were forced to flee from Bhutan to Nepal.

- Ban Mai Nai Soi refugee camp in Burma hosted 19,512 Karenni people in 2008.

- Mae La refugee camp in Thailand hosts around 50,000 Burmese of the Karen ethnicity.

- There are two camps, Nayapara and Kutupalong, in south-eastern Bangladesh hosting 30,000 registered Rohingya people who fled from Myanmar. It is estimated that 200,000 undocumented Rohingya refugees are living outside the camps with little access to humanitarian assistance.[59]

- Galang Refugee Camp in Indonesia accommodated Indochinese refugees between 1979 and 1996.

Middle East

- Camps for Syrian refugees in Iraqi Kurdistan, including Domiz in Dohuk Governorate,[60][61] Arbat in Sulaymaniyah, and Qushtapa, Basirma, Gawilan, Kawergosk and Darashakran in Erbil Governorate.[62] (see also Syrian refugee camps in Iraqi Kurdistan)

- Camps for Syrian refugees in Turkey, such as Urfa, Kilis Oncupinar, Gaziantep and those in the Hatay Province that were opened in 2011 (see also Syrian refugee camps in Turkey).

- Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, hosting 144,000 Syrian refugees as of July 2013, although the population in November 2013 had dropped to around 112,000 as the Syrian civil war continues.[63]

- Mrajeeb Al Fhood refugee camp in Jordan, hosting 4,200 and Azraq camp, hosting 26,000 Syrian refugees.

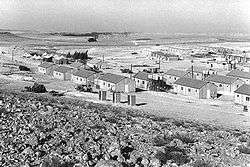

- Immigrant camps (Israel) (1947–1950) and Ma'abarot transition camps (1950–1963) to accommodate Jewish refugees and immigrants in Israel.

- Palestinian refugee camps were opened between 1948 and 1968. The 59 camps are recognized by the UNRWA and host 1.5 million refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. These camps contain the world's largest and oldest refugee population. Yarmouk camp, just outside Damascus, is one of them and was once home to half a million Palestinian refugees (about 18,000 in 2015). It has been besieged by Bashar al-Assad's regime in 2012 and came again under attack by the Islamic State group in 2015.

Aerial view of Zaatari Refugee Camp in Jordan, July 18, 2013.

Aerial view of Zaatari Refugee Camp in Jordan, July 18, 2013. - Three camps received Palestinian refugees from Iraq: Al Tanf, Al Hol and Al Waleed. There are around 2,000 in Al Hol and in Al Waleed camp, which is on the Iraqi side of the border. Al Tanf, which was on the Syrian side and hosted 1,600 Palestinians, was closed in 2010.[64]

- Al Kharaz in Yemen hosts 14,000 refugees from Somalia who crossed the Gulf of Aden.[65]

- Al-Mazraq camps (1-3) host around 24,000 internally displaced persons in Yemen.[66]

- There are camps for displaced Syrians within Syria such as Qah or the Olive Tree Camp.

Europe

- Cyprus internment camps (1946–1949) to accommodate Jewish refugees and Holocaust survivors

- Lampedusa immigrant reception center for refugees, asylum seekers and other immigrants on the Italian island of Lampedusa.

- Ħal Far, Malta for African immigrants.

- Timisoara Emergency Transit Centre for refugees in Romania.[67] It can accommodate up to 200 people and provides a temporary safe haven – for up to six months – for individuals or groups who need to be evacuated immediately from life-threatening situations before being resettled.[68]

- Sangatte camp[69] and the Calais jungle in northern France.[70]

- The Oksbøl Refugee Camp was the largest camp for German Refugees in Denmark after World War II.

- Traiskirchen camp in eastern Austria hosts refugees that come to Europe as part of the European migrant crisis.

- Friedland refugee camp in Germany hosted refugees who fled from the former eastern territories of Germany at the end of World War II, between 1944 and 1950. Between 1950 and 1987 it was a transit centre for East German (GDR) citizens who wanted to flee to Germany (FRG).

- International Refugee Organization camp at Lesum, near Bremen, Germany.

- Kjesäter in Sweden was a refugee camp and transit centre for Norwegian refugees fleeing Nazi persecution during World War II.

- Kløvermarken in Denmark was a refugee camp that hosted 19,000 German refugees between 1945 and 1949.

- Vrela Ribnička refugee camp in Montenegro was built in 1994 and houses refugees of Bosnian origin who were displaced during the Yugoslav Wars.

- Čardak was a camp in Serbia, for Serbs who fled from Croatia and Bosnia.

- Bagnoli camp in Naples, Italy, housed up to 10,000 refugees from Eastern Europe between 1946 and 1951.

Refugee camps by country and population

| Country | Camp | 2015 | 2014 [71] | 2013 [72] | 2012 [73] | 2011 [74] | 2010 [75] | 2009 [76] | 2008 [77] | 2007 [78] | 2006 [79] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chad | Am Nabak | 25,553 | 24,513 | 23,611 | 20,395 | 18,087 | 17,402 | 16,696 | 16,701 | 16,504 | ||

| Chad | Amboko | 11,819 | 10,719 | 11,297 | 11,627 | 11,111 | 11,671 | 12,057 | 12,002 | 12,062 | ||

| Kenya | Dagahaley, Dadaab | 88,486 | 104,565 | 121,127 | 122,214 | 93,470 | 93,179 | 65,581 | 39,626 | 39,526 | ||

| Chad | Djabal | 20,809 | 19,635 | 18,890 | 18,083 | 17,200 | 15,693 | 17,153 | 15,602 | 15,162 | ||

| Yemen | Al Kharaz | 16,500 | 16,816 | 19,047 | 16,904 | 14,100 | 16,466 | 11,394 | 9,491 | 9,298 | ||

| Chad | Breidjing | 41,146 | 39,797 | 37,494 | 35,938 | 34,465 | 32,559 | 32,669 | 30,077 | 28,932 | ||

| Malawi | Dzaleka | 5,874 | 16,935 | 16,664 | 16,853 | 12,819 | 10,275 | 9,425 | 8,690 | 4,950 | ||

| Chad | Farchana | 27,548 | 26,292 | 24,419 | 23,323 | 21,983 | 20,915 | 21,183 | 19,815 | 18,947 | ||

| Kenya | Hagadera, Dadaab | 106,968 | 114,729 | 139,483 | 137,528 | 101,506 | 83,518 | 90,403 | 70,412 | 59,185 | ||

| Sudan | Girba | 6,306 | 6,295 | 6,252 | 5,570 | 5,592 | 5,645 | 5,120 | 9,081 | 8,996 | ||

| Chad | Gondje | 12,138 | 11,349 | 11,717 | 10,006 | 9,586 | 11,184 | 12,700 | 12,664 | 12,624 | ||

| Kenya | Ifo, Dadaab | 83,750 | 99,761 | 98,294 | 118,972 | 97,610 | 79,424 | 79,469 | 61,832 | 54,157 | ||

| Chad | Iridimi | 22,908 | 21,976 | 21,083 | 21,329 | 18,859 | 18,154 | 19,531 | 18,269 | 17,380 | ||

| Kenya | Kakuma | 153,959 | 128,540 | 107,205 | 85,862 | 69,822 | 64,791 | 53,068 | 62,497 | 90,457 | ||

| Sudan | Kilo 26 | 8,391 | 8,303 | 8,310 | 7,634 | 7,608 | 7,610 | 7,133 | 12,690 | 11,423 | ||

| Chad | Kounoungou | 21,960 | 20,876 | 19,143 | 18,251 | 16,927 | 16,237 | 18,514 | 13,500 | 13,315 | ||

| Bangladesh | Kutapalong | 13,176 | 12,626 | 12,404 | 11,706 | 11,469 | 11,251 | 11,047 | 10,708 | 10,144 | ||

| Thailand | Mae La | 46,978 | 25,156 | 26,690 | 27,629 | 29,188 | 30,073 | 32,862 | 38,130 | 46,148 | ||

| Thailand | Mae La Oon | 12,245 | 8,675 | 9,611 | 10,204 | 11,991 | 13,811 | 13,478 | 13,450 | 14,366 | ||

| Thailand | Mae Ra Ma Luang | 13,825 | 8,421 | 9,414 | 10,269 | 11,749 | 13,571 | 11,304 | 11,578 | 12,840 | ||

| Chad | Mile | 21,723 | 20,818 | 19,823 | 18,853 | 17,382 | 14,221 | 17,476 | 16,202 | 15,557 | ||

| Bangladesh | Nayapara | 19,179 | 18,288 | 18,066 | 17,729 | 17,547 | 17,091 | 17,076 | 16,679 | 16,010 | ||

| Thailand | Nu Po | 13,372 | 7,927 | 15,715 | 15,982 | 9,262 | 9,800 | 11,113 | 13,377 | 13,131 | ||

| Tanzania | Nyarugusu | 57,267 | 68,888 | 68,132 | 63,551 | 62,726 | 62,184 | 49,628 | 50,841 | 52,713 | ||

| Chad | Oure Cassoni | 36,466 | 35,415 | 33,267 | 36,168 | 32,206 | 31,189 | 28,430 | 28,035 | 26,786 | ||

| Ethiopia | Shimelba | 6,106 | 5,885 | 6,033 | 8,295 | 9,187 | 10,135 | 10,648 | 16,057 | 13,043 | ||

| India | Tamil Nadu | 65,057 | 65,674 | 67,165 | 68,152 | 69,998 | 72,883 | 73,286 | 72,934 | 69,609 | ||

| Chad | Touloum | 29,683 | 28,501 | 27,940 | 27,588 | 24,500 | 26,532 | 24,935 | 23,131 | 22,358 | ||

| Chad | Treguine | 21,801 | 20,990 | 19,957 | 19,099 | 17,820 | 17,000 | 17,260 | 15,718 | 14,921 | ||

| Sudan | Um Gargur | 10,269 | 10,172 | 8,947 | 8,550 | 8,641 | 8,715 | 8,180 | 10,104 | 9,845 | ||

| Thailand | Um Pium | 16,109 | 9,816 | 10,581 | 11,017 | 11,742 | 12,494 | 14,051 | 19,397 | 19,464 | ||

| Sudan | Wad Sherife | 15,357 | 15,318 | 15,472 | 15,481 | 15,819 | 15,626 | 13,636 | 36,429 | 33,371 | ||

| Ethiopia | Fugnido | 53,218 | 42,044 | 34,247 | 22,692 | 21,770 | 20,202 | - | 18,726 | 27,175 | ||

| Chad | Gaga | 24,591 | 23,236 | 22,266 | 21,474 | 19,888 | 19,043 | 20,677 | 17,708 | 12,402 | ||

| Pakistan | Gamkol | 30,241 | 31,326 | 31,701 | 32,830 | 35,169 | 33,033 | 33,499 | 37,462 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Gandaf | 12,068 | 12,508 | 12,632 | 13,346 | 12,731 | 12,497 | 12,659 | 13,609 | - | ||

| South Sudan | Gendressa | 17,975 | 17,289 | 14,758 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Rwanda | Gihembe | 14,735 | - | 14,006 | 19,827 | 19,853 | 19,407 | 19,027 | 18,081 | 17,732 | ||

| Liberia | Bahn | 5,257 | 8,412 | 8,851 | 5,021 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Bambasi | 14,279 | 13,354 | 12,199 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pakistan | Barakai | 24,786 | 25,909 | 26,739 | 28,093 | 32,077 | 28,597 | 28,851 | 30,266 | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Tongo | 11,075 | 10,399 | 9,518 | 9,605 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Chad | Yaroungou | - | - | 11,594 | 10,916 | 10,544 | 11,925 | 16,573 | 13,352 | 15,260 | ||

| South Sudan | Yusuf Batil | 40,240 | 39,033 | 36,754 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Jordan | Zaatari | 84,773 | 145,209 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pakistan | Thall | 12,247 | 12,847 | 12,976 | 13,468 | 15,419 | 15,269 | 15,602 | 17,266 | - | ||

| Thailand | Tham Hin | 7,406 | - | 7,242 | 7,150 | 4,282 | - | 5,078 | 6,007 | 7,767 | ||

| Nepal | Timai | - | - | - | - | 7,058 | 8,553 | 9,935 | 10,421 | 10,413 | ||

| Pakistan | Timer | 8,690 | 8,603 | 8,665 | 11,161 | 11,764 | 11,839 | 12,080 | 13,919 | - | ||

| Algeria | Tindouf | 90,000 | 90,000 | 90,000 | 90,000 | 90,000 | 90,000 | 90,000 | 90,000 | 90,000 | ||

| Pakistan | Old Akora | 34,789 | 36,384 | 36,693 | 37,736 | 42,872 | 37,019 | 37,757 | 41,647 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Old Shamshatoo | 48,268 | 52,835 | 53,573 | 54,502 | 61,205 | 58,804 | 58,773 | 66,556 | - | ||

| Namibia | Osire | - | - | - | - | - | 8,506 | 8,122 | 7,730 | 6,486 | ||

| Uganda | Pader | - | - | - | 6,677 | 38,550 | 90,000 | 196,000 | - | - | ||

| Pakistan | Padhana | 9,362 | 9,775 | 9,892 | 10,075 | 11,393 | 10,380 | 10,403 | 10,564 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Panian | 53,816 | 56,295 | 56,820 | 58,819 | 67,332 | 61,822 | 62,293 | 65,033 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Pir Alizai | 7,681 | 9,204 | 9,771 | 10,243 | 15,157 | 13,802 | 14,710 | 16,563 | - | ||

| Nepal | Sanischare | - | 6,599 | 9,212 | 10,173 | 13,649 | 16,745 | 20,128 | 21,386 | 21,285 | ||

| Pakistan | Saranan | 18,248 | 20,744 | 21,218 | 21,927 | 26,786 | 24,119 | 24,272 | 24,625 | - | ||

| Sudan | Shagarab | 34,039 | 34,147 | 37,428 | 27,809 | 24,104 | 16,562 | 14,990 | 22,706 | 21,999 | ||

| Ethiopia | Sheder | 12,263 | 11,248 | 11,882 | 11,326 | 10,458 | 7,964 | 6,567 | - | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Sherkole | 10,171 | 9,737 | 7,527 | 8,962 | - | - | - | 8,989 | 13,958 | ||

| Pakistan | Surkhab | 5,764 | 7,012 | 7,214 | 7,422 | 12,304 | 11,789 | 11,877 | 12,225 | - | ||

| Burkina Faso | Mentao | 10,953 | 11,907 | 6,905 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Tanzania | Mtabila | - | - | - | 37,554 | 36,789 | 36,009 | 45,247 | 90,680 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Munda | 9,388 | 9,941 | 10,100 | 10,341 | 12,728 | 11,225 | 11,386 | 13,274 | - | ||

| Burundi | Musasa | 7,001 | 6,829 | 6,500 | 6,330 | 6,153 | 6,572 | 5,984 | 6,764 | - | ||

| Zambia | Mwange | - | - | - | - | - | 5,820 | 14,429 | 17,911 | 21,179 | ||

| Uganda | Nakivale | 66,691 | - | 64,373 | - | - | 52,249 | 42,113 | 33,176 | 25,692 | ||

| Pakistan | New Durrani | - | 14,978 | 12,438 | 14,397 | 10,458 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pakistan | Oblan | 9,015 | 9,294 | 9,331 | 9,474 | 10,065 | 9,560 | 9,624 | 11,564 | - | ||

| Liberia | PTP | 15,300 | 12,734 | 9,353 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Uganda | Rhino Camp | 18,762 | - | 4,266 | - | - | - | 5,582 | 14,328 | 18,493 | ||

| Uganda | Rwamwanja | 52,489 | - | 29,797 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Liberia | Little Wlebbo | 8,481 | 10,009 | 8,399 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Tanzania | Lugufu | - | - | - | - | - | - | 28,995 | 45,308 | 75,254 | ||

| Tanzania | Lukole | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25,490 | 39,685 | ||

| Thailand | Mai Nai Soi | 12,414 | 9,725 | 11,730 | 12,244 | 12,252 | - | 19,311 | 19,103 | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Mai Ayni | 17,808 | 18,207 | 15,715 | 14,432 | 12,255 | 15,762 | - | - | - | ||

| Iraq | Makhmour | - | 10,534 | 10,552 | 10,240 | 11,101 | - | 10,912 | 10,728 | 11,900 | ||

| Mozambique | Maratane | - | 7,707 | 7,398 | 9,576 | 6,646 | - | - | - | 5,019 | ||

| Uganda | Masindi | - | - | - | 6,500 | 20,000 | 55,000 | 55,000 | - | - | ||

| Zambia | Mayukwayukwa | - | 11,366 | 10,117 | - | - | 10,184 | 10,474 | 10,660 | 10,636 | ||

| Mauritania | M'bera | 48,910 | 66,392 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Zambia | Meheba | 8,410 | 17,806 | 17,708 | - | - | 14,970 | 15,763 | 13,892 | 13,732 | ||

| Ethiopia | Melkadida | 44,645 | 43,480 | 42,365 | 40,696 | 25,491 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Chad | Abgadam | 21,571 | 21,914 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Adi Harush | 34,090 | 25,801 | 23,562 | 15,982 | 6,923 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Uganda | Adjumani | 96,926 | 11,986 | 9,279 | - | 7,365 | 28,000 | 21,714 | 52,784 | 54,051 | ||

| South Sudan | Ajuong Thok | 15,015 | 6,691 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Djibouti | Ali Adde | 18,208 | 17,523 | 17,354 | 19,500 | 14,333 | - | 8,924 | 6,376 | 6,739 | ||

| Uganda | Amuru | - | - | - | 6,779 | 35,475 | 98,000 | 234,000 | - | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Awbarre / Teferiber | 12,965 | 13,752 | 13,331 | 13,426 | 13,120 | 12,293 | 11,045 | 8,581 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Azakhel | 20,191 | 21,132 | 21,231 | 21,398 | 26,342 | 23,963 | 24,258 | 25,649 | - | ||

| Jordan | Azraq | 11,315 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pakistan | Badaber | 23,918 | 25,589 | 26,227 | 28,729 | 31,345 | 30,107 | 30,327 | 36,614 | - | ||

| Nepal | Beldangi 1 & 2 | 18,379 | 24,377 | 31,976 | 33,855 | 36,761 | 42,122 | 50,350 | 52,967 | 52,997 | ||

| Chad | Belome | 26,521 | 23,949 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Bokolmanyo | 41,665 | 41,670 | 40,423 | 38,501 | 14,988 | 21,707 | - | - | - | ||

| Ghana | Buduburam | - | - | - | - | - | 11,334 | 14,992 | 26,179 | 36,159 | ||

| Ethiopia | Buramino | 39,471 | 40,114 | 35,207 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Burundi | Bwagiriza | 9,480 | 9,289 | 10,105 | 6,159 | 4,526 | 2,896 | |||||

| Niger | Abala | 12,938 | 12,216 | 11,126 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pakistan | Chakdara | 10,704 | 11,184 | 11,242 | 13,354 | 18,752 | 16,069 | 16,427 | 17,420 | - | ||

| Kenya | Ifo 2, Dadaab | 52,310 | 65,693 | 69,269 | 64,945 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Kenya | Kambioos, Dadaab | 21,035 | 20,435 | 18,126 | 10,833 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Chad | Dogdore | - | - | 19,500 | 19,500 | 19,500 | - | - | - | - | ||

| South Sudan | Doro | 50,087 | 47,422 | - | 28,709 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Chad | Dosseye | 21,522 | 15,766 | 9,922 | 9,724 | 9,433 | 9,607 | 8,556 | 6,158 | 2,277 | ||

| Pakistan | Girdi Jungle | 17,376 | 22,065 | 22,340 | 22,740 | 31,642 | 29,716 | 29,717 | 29,783 | - | ||

| Nepal | Goldhap | - | - | - | - | 4,764 | 6,356 | 8,315 | 9,694 | 9,602 | ||

| Burkina Faso | Goudebo | 9,403 | 9,287 | 4,943 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Chad | Goz Amer | 31,477 | 30,105 | 27,091 | 25,841 | 24,608 | 21,449 | 21,640 | 20,097 | 19,261 | ||

| Chad | Goz Beïda | - | - | 60,500 | 73,000 | 73,000 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Uganda | Gulu | - | - | - | - | 9,043 | 44,000 | 156,000 | - | - | ||

| Yemen | Al-Mazrak | - | 12,416 | 12,308 | 12,075 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Hilaweyn | 38,890 | 37,305 | 30,960 | 25,747 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Hitsats | 33,235 | 10,226 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Uganda | Impevi | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7,453 | 22,061 | 23,331 | ||

| Niger | Intikane | 12,738 | 11,221 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Sri Lanka | Jaffna | - | - | - | 6,436 | 9,108 | - | - | 10,522 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Jalala | 12,968 | 13,278 | 13,421 | 14,042 | 16,094 | 13,854 | 14,115 | 16,160 | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Kobe | 39,214 | 36,488 | 31,656 | 26,033 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pakistan | Koga | 8,404 | 8,738 | 8,893 | 9,216 | 9,183 | 9,264 | 10,458 | 10,766 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Kot Chandna | 13,796 | 14,664 | 14,889 | 15,100 | 17,787 | 15,012 | 15,037 | 15,130 | - | ||

| Ethiopia | Kule | 46,314 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pakistan | Jalozai | - | 22,076 | 57,771 | 32,499 | 100,748 | 30,955 | 32,155 | 83,616 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Kababian | 11,044 | 11,664 | 12,167 | 12,504 | 13,214 | 12,335 | 11,291 | 14,729 | - | ||

| Pakistan | Kacha Gari | - | - | - | - | - | 28,365 | 24,554 | 26,721 | - | ||

| Zambia | Kala | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12,768 | 16,877 | 19,143 | ||

| South Sudan | Kaya | 21,918 | 18,788 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Uganda | Kyaka II | 22,616 | - | 18,055 | - | - | 17,442 | 14,750 | 18,229 | 16,410 | ||

| Ethiopia | Kebribeyah | - | 15,788 | 16,009 | 16,408 | 16,601 | 16,496 | 16,132 | 16,879 | 16,399 | ||

| Iran | Rafsanjan | - | - | - | - | 6,852 | 6,630 | - | - | 12,715 | ||

| Pakistan | Khaki | 14,101 | 14,698 | 14,939 | 15,768 | 16,221 | 15,933 | 16,010 | 16,267 | - | ||

| Nepal | Khudunabari | - | - | - | 9,032 | 11,067 | 12,054 | 13,254 | 13,226 | 13,506 | ||

| Burundi | Kinama | 9,796 | 9,759 | 9,480 | 9,369 | 8,447 | - | - | ||||

| Uganda | Kitgum | - | - | - | 7,070 | 12,290 | 122,000 | 164,000 | - | - | ||

| Rwanda | Kiziba | - | - | 15,927 | 18,919 | 18,888 | 18,693 | 18,323 | 18,130 | 17,978 | ||

| Pakistan | Khairābād-Kund | - | - | 12,961 | 12,921 | 11,839 | 11,669 | 11,686 | 14,674 | - | ||

| Uganda | Kyangwali | 40,023 | - | 21,280 | - | - | 20,606 | 13,434 | 20,109 | 19,132 | ||

| Guinea | Laine | - | - | - | - | 4,187 | - | - | 5,185 | 11,406 | ||

| Ethiopia | Leitchour | 47,711 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Botswana | Dukwe | 2,833[80] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

See also

- Displaced persons camp

- Immigration detention

- Tent city

- Transitional shelter

- United Nations Border Relief Operation which administered camps in Thailand 1982-1993.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East

- Refugee Nation

References

- ↑ UNHCR: "Displacement: The New 21st Century Challenge," 2012; p. 35.

- ↑ Sean Smith. "Migrant life in Calais' Jungle refugee camp - a photo essay". the Guardian. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ UNHCR Global Trends 2015, p. 58

- ↑ Tom Corsellis, Antonella Vitale, Transitional Settlement: Displaced Populations, Oxfam GB., University of Cambridge; Shelter project; Oxfam, 2005 ISBN 0855985348

- 1 2 David Miliband, "From sector to system: reform and renewal in humanitarian aid Media," IRC Global Communications, New York, NY, April 27, 2016.

- ↑ Médecins Sans Frontières, Refugee Health: An approach to emergency situations, Macmillan, Oxford: 1997.

- 1 2 https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/45582/camp-planning-standards-planned-settlements

- ↑ McAlister, Elizabeth (2013). "Humanitarian Adhocracy, Transnational New Apostolic Missions, and Evangelical Anti-Dependency in a Haitian Refugee Camp". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 16 (4): 11–34. doi:10.1525/nr.2013.16.4.11.

- ↑ "Syrian refugee camps in Turkish territory". astrium-geo.com.

- ↑ Beaudou A., Cambrézy L., Zaiss R., "Geographical Information system, environment and camp planning in refugee hosting areas: Approach, methods and application in Uganda," Institute for Research in Development (IRD); November 2003.

- ↑ Alain Beaudou, Luc Cambrézy, Marc Souris, "Environment, cartography, demography and geographical information system in the refugee camps Dadaab, Kakuma – Kenya," October 1999 UNHCR – IRD (ORSTOM).

- ↑ Better Shelter Unit (Refugee Housing Unit) Designing an alternative shelter for emergency relief and beyond, UNHCR.

- ↑ Refugee Camp Priority: Health and Sanitation, CRS

- ↑ Ruth Schoeffl, "Liquid treasure: The challenge of providing drinking water in a new refugee camp," UNHCR, 4 July 2013

- ↑ Jay P. Graham and Matthew L. Polizzotto, "Pit Latrines and Their Impacts on Groundwater Quality: A Systematic Review," Environ Health Perspect. 2013 May; 121(5): 521–530.

- ↑ "Development assistance and refugees" (PDF). Oxford University, 2009. Retrieved 9 Sep 2013.

- ↑ "Promoting Livelihoods and Self-reliance" (PDF). UNHCR, 2011. Retrieved 9 Sep 2013.

- ↑ "Investing in refugees: new solutions for old problems". The Guardian, 15 July 2013. Retrieved 9 Sep 2013.

- ↑ R. Jaji, Journal of Refugee Studies Vol. 25, No. 2, 2011: Social Technology and Refugee Encampment in Kenya

- ↑ Barber, Ben. "Feeding refugees, or war? The dilemma of humanitarian aid." Foreign Affairs (1997): 8-14.

- ↑ Van Der Meeren, Rachel. "Three decades in exile: Rwandan refugees 1960-1990." J. Refugee Stud. 9 (1996): 252.

- ↑ Reynell, J. Political Pawns: Refugees on the Thai-Kampuchean Border. Oxford: Refugee Studies Programme, 1989.

- 1 2 "IRIN Africa - ERITREA-SUDAN: A forgotten refugee problem - Eritrea - Sudan - Early Warning - Refugees/IDPs". IRINnews. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ UNHCR (2006). The state of the world’s refugees 2006: Human displacement in the new millennium. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Daniel, E.V., and Knudsen, J. eds. Mistrusting Refugees 1995, University of California Press. ISBN 9780520088993

- ↑ "UN Refugee Chief: Voluntary Return of Somali Refugees a Global Priority". VOA. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - UNHCR welcomes Tanzania's decision to naturalize tens of thousands of Burundian refugees". UNHCR. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ Refugees and New Zealand at the Refugee Services

- ↑ "Gateway Protection Programme". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ Esri,Marina Koren. "Where Are the 50 Most Populous Refugee Camps?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "CAR: The Fate of Refugees in Southern Chad". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). "South Sudan Situation - Uganda". UNHCR South Sudan Situation. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - UNHCR tackles Hepatitis E outbreak that kills 16 Sudanese refugees". UNHCR. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "Future of Liberian Refugees in Ghana Uncertain". VOA.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refugees in the Horn of Africa: Somali Displacement Crisis - Kenya - Dadaab". UNHCR Refugees in the Horn of Africa: Somali Displacement Crisis. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Ten Largest Refugee Camps". WSJ. 7 September 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ Esri Story Maps. "Fifty Largest Refugee Camps - A story map presented by Esri". Esri. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "Libyan Refugee Crisis Called a 'Logistical Nightmare'". The New York Times. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Malawi". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 Jack Todd. "10 Largest Refugee Camps in the World". BORGEN. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ Nicole Lee. "A life of escaping conflict: 'I don't feel like a Burundian – I am a refugee'". the Guardian. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "U.N. expands refugee camp in Kenya as South Sudan conflict rages". Reuters. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Somali refugees in Ethiopia's Dollo Ado exceed 150,000 as rains hit camps". UNHCR. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ G. Verdirame, Journal of Refugee Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, 1999: Human Rights and Refugees: The Case of Kenya

- ↑ "Refugees From Sudan Strain Ethiopia Camps". The New York Times. 1 May 1988. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/4c0903ca9.pdf

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Djibouti". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/4c08f2409.pdf

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Cameroon". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Rwanda". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Opération Sahel - Mali Situation - Burkina Faso - Camp de Mentao". UNHCR Opération Sahel. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Liberia". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Mauritania". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "UNHCR - Refugees Daily". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/wikileaks-files/somalia-wikileaks/8302115/TONGOGARA-REFUGEE-CAMP-TRIP-REPORT.html

- ↑ Dobson, Chris (19 July 1992). "A day at the world's largest 'prison'". South China Morning Post.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Sri Lanka". unhcr.org.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Pakistan". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - The young and the hopeless in Bangladesh's camps". UNHCR. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ Life getting harder for Syrian refugees in Iraqi Kurdistan

- ↑ "Syrian refugee women in Domiz camp struggling for their rights in Iraqi Kurdistan". kvinnatillkvinna.se.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). "Syria Regional Refugee Response - Iraq". UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). "Syria Regional Refugee Response - Jordan - Mafraq Governorate - Zaatari Refugee Camp". UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - End of long ordeal for Palestinian refugees as desert camp closes". UNHCR. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "IRIN Middle East - YEMEN: Somali refugees hope for better life beyond Kharaz camp - Somalia - Yemen - Children - Education - Gender Issues - Refugees/IDPs". IRINnews. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "UNHCR - Refugees Daily". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "The Timisoara ETC: a gateway to freedom and a new life". UNHCR RRCE. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR - Refugees evacuated from desert camp to safe haven in Romania". UNHCR. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "Sangatte refugee camp". London: The Guardian. 23 May 2002.

- ↑ Gentleman, Amelia (3 November 2015). "The horror of the Calais refugee camp: 'We feel like we are dying slowly'". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/statisticalyearbook/2014-annex-tables.zip

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2013/annex_tables.zip

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2012/2012_Statistical_Yearbook_annex_tables_v1.zip

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2011/2011_Statistical_Yearbook_annex_tables_v1.zip

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2010/2011-SYB10-annex-tables.zip

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2009/2009-Statistical-Yearbook-Annex-Tables.zip

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2008/08-TPOC-TB_v5_external_PW.zip

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2007/annextables.zip

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/static/statistical_yearbook/2006/annextables.zip

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Botswana Fact Sheet". UNHCR. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Refugee camps. |

- UNHCR - The UN Refugee Agency - Data Sharing Tool - Interactive map and passport of every refugee camp, data sharing tool updated by every organisation in the camp

- Camp Management Toolkit published by Norwegian Refugee Council

- Shelter Library Resource for organisations responding to the transitional settlement and shelter needs of displaced populations

- Refugee Camp in the Heart of the City. An awareness raising touring event organized by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)

- U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants' Campaign to End Refugee Warehousing in refugee camps around the world, people are confined to their settlement and denied their basic rights.

- Refuge Essay on Life in a Refugee Camp

- Thai-Cambodian Border Camps

- An Assessment of Sphere Humanitarian Standards for Shelter and Settlement Planning in Kenya’s Dadaab Refugee Camps

- The open source and open hardware OLPC One School Per Child Initiative link Refugee Camps