Reference range

| Reference ranges |

|---|

|

In: |

In health-related fields, a reference range or reference interval is the range of values for a physiologic measurement in healthy persons (for example, the amount of creatinine in the blood, or the partial pressure of oxygen). It is a basis for comparison (a frame of reference) for a physician or other health professional to interpret a set of test results for a particular patient. Some important reference ranges in medicine are reference ranges for blood tests and reference ranges for urine tests.

The standard definition of a reference range (usually referred to if not otherwise specified) originates in what is most prevalent in a reference group taken from the general (i.e. total) population. This is the general reference range. However, there are also optimal health ranges (ranges that appear to have the optimal health impact) and ranges for particular conditions or statuses (such as pregnancy reference ranges for hormone levels).

Values within the reference range (WRR) are those within the normal distribution and are thus often described as within normal limits (WNL). The limits of the normal distribution are called the upper reference limit (URL) or upper limit of normal (ULN) and the lower reference limit (LRL) or lower limit of normal (LLN). In health care–related publishing, style sheets sometimes prefer the word reference over the word normal to prevent the nontechnical senses of normal from being conflated with the statistical sense. Values outside a reference range are not necessarily pathologic, and they are not necessarily abnormal in any sense other than statistically. Nonetheless, they are indicators of probable pathosis. Sometimes the underlying cause is obvious; in other cases, challenging differential diagnosis is required to determine what is wrong and thus how to treat it.

Standard definition

The standard definition of a reference range for a particular measurement is defined as the prediction interval between which 95% of values of a reference group fall into, in such a way that 2.5% of the time a sample value will be less than the lower limit of this interval, and 2.5% of the time it will be larger than the upper limit of this interval, whatever the distribution of these values.[1]

Reference ranges that are given by this definition are sometimes referred as standard ranges.

Regarding the target population, if not otherwise specified, a standard reference range generally denotes the one in healthy individuals, or without any known condition that directly affects the ranges being established. These are likewise established using reference groups from the healthy population, and are sometimes termed normal ranges or normal values (and sometimes "usual" ranges/values). However, using the term normal may not be appropriate as not everyone outside the interval is abnormal, and people who have a particular condition may still fall within this interval.

However, reference ranges may also be established by taking samples from the whole population, with or without diseases and conditions. In some cases, diseased individuals are taken as the population, establishing reference ranges among those having a disease or condition. Preferably, there should be specific reference ranges for each subgroup of the population that has any factor that affects the measurement, such as, for example, specific ranges for each sex, age group, race or any other general determinant.

Establishment methods

Methods for establishing reference ranges are mainly based on assuming a normal distribution or a log-normal distribution, or directly from percentages of interest, as detailed respectively in following sections.

Normal distribution

The 95% prediction interval, is often estimated by assuming a normal distribution of the measured parameter, in which case it can alternatively be defined as the interval limited by 1.96[2] (often rounded up to 2) population standard deviations from either side of the population mean (also called the expected value). However, in the real world, neither the population mean nor the population standard deviation are known. They both need to be estimated from a sample, whose size can be designated n. The population standard deviation is estimated by the sample standard deviation and the population mean is estimated by the sample mean (also called mean or arithmetic mean). To account for these estimations, the 95% prediction interval (95% PI) is calculated as:

where is the 97.5% quantile of a Student's t-distribution with n-1 degrees of freedom.

When the sample size is large (n≥30)

This method is often acceptably accurate if the standard deviation, as compared to the mean, is not very large. A more accurate method is to perform the calculations on logarithmized values, as described in separate section later.

The following example of this (not logarithmized) method is based on values of fasting plasma glucose taken from a reference group of 12 subjects:[3]

| Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) in mmol/L | Deviation from mean m | Squared deviation from mean m | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1 | 5.5 | 0.17 | 0.029 |

| Subject 2 | 5.2 | -0.13 | 0.017 |

| Subject 3 | 5.2 | -0.13 | 0.017 |

| Subject 4 | 5.8 | 0.47 | 0.221 |

| Subject 5 | 5.6 | 0.27 | 0.073 |

| Subject 6 | 4.6 | -0.73 | 0.533 |

| Subject 7 | 5.6 | 0.27 | 0.073 |

| Subject 8 | 5.9 | 0.57 | 0.325 |

| Subject 9 | 4.7 | -0.63 | 0.397 |

| Subject 10 | 5 | -0.33 | 0.109 |

| Subject 11 | 5.7 | 0.37 | 0.137 |

| Subject 12 | 5.2 | -0.13 | 0.017 |

| Mean = 5.33 (m) n=12 | Mean = 0.00 | Sum/(n-1) = 1.95/11 =0.18 = standard deviation (s.d.) |

As can be given from, for example, a table of selected values of Student's t-distribution, the 97.5% percentile with (12-1) degrees of freedom corresponds to

Subsequently, the lower and upper limits of the standard reference range are calculated as:

Thus, the standard reference range for this example is estimated to be 4.4 to 6.3 mmol/L.

Confidence interval of limit

The confidence interval of a standard reference range limit as estimated assuming a normal distribution can be calculated from the standard deviation of a standard reference range limit (SDSRRL), as, in turn, can be estimated by a diagram such as the one shown at right.

Taking the example from the previous section, the number of samples is 12, corresponding to a SDSRRL of approximately 0.5 standard deviations of the primary value, that is, approximately 0.42 mmol/L * 0.5 = 0.21 mmol/L. Thus, the 95% confidence interval is of a reference range limit can be calculated as:

where:

- LlciLlrr is the Lower limit of the confidence interval of the Lower limit of the standard reference range

- Llrr is the Lower limit of the standard reference range

- SDSRRL is the standard deviation of the standard reference range limit

Likewise:

where:

- UlciLlrr is the Upper limit of the confidence interval of the Lower limit of the standard reference range

- Llrr is the Lower limit of the standard reference range

- SDSRRL is the standard deviation of the standard reference range limit

Thus, the lower limit of the reference range can be written as 4.4 (CI 3.9-4.9) mmol/L.

Likewise, with similar calculations, the upper limit of the reference range can be written as 6.3 (CI 5.8-6.8) mmol/L.

These confidence intervals reflect random error, but do not compensate for systematic error, which in this case can arise from, for example, the reference group not having fasted long enough before blood sampling.

As a comparison, actual reference ranges used clinically for fasting plasma glucose are estimated to have a lower limit of approximately 3.8[4] to 4.0,[5] and an upper limit of approximately 6.0[5] to 6.1.[6]

Log-normal distribution

In reality, biological parameters tend to have a log-normal distribution,[7] rather than the arithmetical normal distribution (which is generally referred to as normal distribution without any further specification).

An explanation for this log-normal distribution for biological parameters is: The event where a sample has half the value of the mean or median tends to have almost equal probability to occur as the event where a sample has twice the value of the mean or median. Also, only a log-normal distribution can compensate for the inability of almost all biological parameters to be of negative numbers (at least when measured on absolute scales), with the consequence that there is no definite limit to the size of outliers (extreme values) on the high side, but, on the other hand, they can never be less than zero, resulting in a positive skewness.

As shown in diagram at right, this phenomenon has relatively small effect if the standard deviation (as compared to the mean) is relatively small, as it makes the log-normal distribution appear similar to an arithmetical normal distribution. Thus, the arithmetical normal distribution may be more appropriate to use with small standard deviations for convenience, and the log-normal distribution with large standard deviations.

In a log-normal distribution, the geometric standard deviations and geometric mean more accurately estimate the 95% prediction interval than their arithmetic counterparts.

Necessity

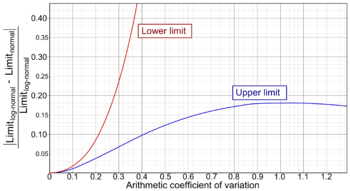

The necessity to establish a reference range by log-normal distribution rather than arithmetic normal distribution can be regarded as depending on how much difference it would make to not do so, which can be described as the ratio:

where:

- Limitlog-normal is the (lower or upper) limit as estimated by assuming log-normal distribution

- Limitnormal is the (lower or upper) limit as estimated by assuming arithmetically normal distribution.

This difference can be put solely in relation to the coefficient of variation, as in the diagram at right, where:

where:

- s.d. is the arithmetic standard deviation

- m is the arithmetic mean

In practice, it can be regarded as necessary to use the establishment methods of a log-normal distribution if the difference ratio becomes more than 0.1, meaning that a (lower or upper) limit estimated from an assumed arithmetically normal distribution would be more than 10% different from the corresponding limit as estimated from a (more accurate) log-normal distribution. As seen in the diagram, a difference ratio of 0.1 is reached for the lower limit at a coefficient of variation of 0.213 (or 21.3%), and for the upper limit at a coefficient of variation at 0.413 (41.3%). The lower limit is more affected by increasing coefficient of variation, and its "critical" coefficient of variation of 0.213 corresponds to a ratio of (upper limit)/(lower limit) of 2.43, so as a rule of thumb, if the upper limit is more than 2.4 times the lower limit when estimated by assuming arithmetically normal distribution, then it should be considered to do the calculations again by log-normal distribution.

Taking the example from previous section, the arithmetic standard deviation (s.d.) is estimated at 0.42 and the arithmetic mean (m) is estimated at 5.33. Thus the coefficient of variation is 0.079. This is less than both 0.213 and 0.413, and thus both the lower and upper limit of fasting blood glucose can most likely be estimated by assuming arithmetically normal distribution. More specifically, the coefficient of variation of 0.079 corresponds to a difference ratio of 0.01 (1%) for the lower limit and 0.007 (0.7%) for the upper limit.

From logarithmized sample values

A method to estimate the reference range for a parameter with log-normal distribution is to logarithmize all the measurements with an arbitrary base (for example e), derive the mean and standard deviation of these logarithms, determine the logarithms located (for a 95% prediction interval) 1.96 standard deviations below and above that mean, and subsequently exponentiate using those two logarithms as exponents and using the same base as was used in logarithmizing, with the two resultant values being the lower and upper limit of the 95% prediction interval.

The following example of this method is based on the same values of fasting plasma glucose as used in the previous section, using e as a base:[3]

| Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) in mmol/L | loge(FPG) | loge(FPG) deviation from mean μlog | Squared deviation from mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1 | 5.5 | 1.70 | 0.029 | 0.000841 |

| Subject 2 | 5.2 | 1.65 | 0.021 | 0.000441 |

| Subject 3 | 5.2 | 1.65 | 0.021 | 0.000441 |

| Subject 4 | 5.8 | 1.76 | 0.089 | 0.007921 |

| Subject 5 | 5.6 | 1.72 | 0.049 | 0.002401 |

| Subject 6 | 4.6 | 1.53 | 0.141 | 0.019881 |

| Subject 7 | 5.6 | 1.72 | 0.049 | 0.002401 |

| Subject 8 | 5.9 | 1.77 | 0.099 | 0.009801 |

| Subject 9 | 4.7 | 1.55 | 0.121 | 0.014641 |

| Subject 10 | 5.0 | 1.61 | 0.061 | 0.003721 |

| Subject 11 | 5.7 | 1.74 | 0.069 | 0.004761 |

| Subject 12 | 5.2 | 1.65 | 0.021 | 0.000441 |

| Mean: 5.33 (m) | Mean: 1.67 (μlog) | Sum/(n-1) : 0.068/11 = 0.0062 = standard deviation of loge(FPG) (σlog) |

Subsequently, the still logarithmized lower limit of the reference range is calculated as:

and the upper limit of the reference range as:

Conversion back to non-logarithmized values are subsequently performed as:

Thus, the standard reference range for this example is estimated to be 4.4 to 6.4.

From arithmetic mean and variance

An alternative method of establishing a reference range with the assumption of log-normal distribution is to use the arithmetic mean and arithmetic value of standard deviation. This is somewhat more tedious to perform, but may be useful for example in cases where a study that establishes a reference range presents only the arithmetic mean and standard deviation, leaving out the source data. If the original assumption of arithmetically normal distribution is shown to be less appropriate than the log-normal one, then, using the arithmetic mean and standard deviation may be the only available parameters to correct the reference range.

By assuming that the expected value can represent the arithmetic mean in this case, the parameters μlog and σlog can be estimated from the arithmetic mean (m) and standard deviation (s.d.) as:

Following the exampled reference group from the previous section:

Subsequently, the logarithmized, and later non-logarithmized, lower and upper limit are calculated just as by logarithmized sample values.

Directly from percentages of interest

Reference ranges can also be established directly from the 2.5th and 97.5th percentile of the measurements in the reference group. For example, if the reference group consists of 200 people, and counting from the measurement with lowest value to highest, the lower limit of the reference range would correspond to the 5th measurement and the upper limit would correspond to the 195th measurement.

This method can be used even when measurement values do not appear to conform conveniently to any form of normal distribution or other function.

However, the reference range limits as estimated in this way have higher variance, and therefore less reliability, than those estimated by an arithmetic or log-normal distribution (when such is applicable), because the latter ones acquire statistical power from the measurements of the whole reference group rather than just the measurements at the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. Still, this variance decreases with increasing size of the reference group, and therefore, this method may be optimal where a large reference group easily can be gathered, and the distribution mode of the measurements is uncertain.

Bimodal distribution

In case of a bimodal distribution (seen at right), it is useful to find out why this is the case. Two reference ranges can be established for the two different groups of people, making it possible to assume a normal distribution for each group. This bimodal pattern is commonly seen in tests that differ between men and women, such as prostate specific antigen.

Interpretation of standard ranges in medical tests

In case of medical tests whose results are of continuous values, reference ranges can be used in the interpretation of an individual test result. This is primarily used for diagnostic tests and screening tests, while monitoring tests may optimally be interpreted from previous tests of the same individual instead.

Probability of random variability

Reference ranges aid in the evaluation of whether a test result's deviation from the mean is a result of random variability or a result of an underlying disease or condition. If the reference group used to establish the reference range can be assumed to be representative of the individual person in a healthy state, then a test result from that individual that turns out to be lower or higher than the reference range can be interpreted as that there is less than 2.5% probability that this would have occurred by random variability in the absence of disease or other condition, which, in turn, is strongly indicative for considering an underlying disease or condition as a cause.

Such further consideration can be performed, for example, by an epidemiology-based differential diagnostic procedure, where potential candidate conditions are listed that may explain the finding, followed by calculations of how probable they are to have occurred in the first place, in turn followed by a comparison with the probability that the result would have occurred by random variability.

If the establishment of the reference range could have been made assuming a normal distribution, then the probability that the result would be an effect of random variability can be further specified as follows:

The standard deviation, if not given already, can be inversely calculated by the fact that the absolute value of the difference between the mean and either the upper or lower limit of the reference range is approximately 2 standard deviations (more accurately 1.96), and thus:

The standard score for the individual's test can subsequently be calculated as:

The probability that a value is of a certain distance from the mean can subsequently be calculated from the relation between standard score and prediction intervals. For example, a standard score of 2.58 corresponds to a prediction interval of 99%,[8] corresponding to a probability of 0.5% that a result is at least such far from the mean in the absence of disease.

Example

Let's say, for example, that an individual takes a test that measures the ionized calcium in the blood, resulting in a value of 1.30 mmol/L, and a reference group that appropriately represents the individual has established a reference range of 1.05 to 1.25 mmol/L. The individual's value is higher than the upper limit of the reference range, and therefore has less than 2.5% probability of being a result of random variability, constituting a strong indication to make a differential diagnosis of possible causative conditions.

In this case, an epidemiology-based differential diagnostic procedure is used, and its first step is to find candidate conditions that can explain the finding.

Hypercalcemia (usually defined as a calcium level above the reference range) is mostly caused by either primary hyperparathyroidism or malignancy,[9] and therefore, it is reasonable to include these in the differential diagnosis.

Using for example epidemiology and the individual's risk factors, let's say that the probability that the hypercalcemia would have been caused by primary hyperparathyroidism in the first place is estimated to be 0.00125 (or 0.125%), the equivalent probability for cancer is 0.0002, and 0.0005 for other conditions. With a probability given as less than 0.025 of no disease, this corresponds to a probability that the hypercalcemia would have occurred in the first place of up to 0.02695. However, the hypercalcemia has occurred with a probability of 100%, resulting adjusted probabilities of at least 4.6% that primary hyperparathyroidism has caused the hypercalcemia, at least 0.7% for cancer, at least 1.9% for other conditions and up to 92.8% for that there is no disease and the hypercalcemia is caused by random variability.

In this case, further processing benefits from specification of the probability of random variability:

The value is assumed to conform acceptably to a normal distribution, so the mean can be assumed to be 1.15 in the reference group. The standard deviation, if not given already, can be inversely calculated by knowing that the absolute value of the difference between the mean and, for example, the upper limit of the reference range, is approximately 2 standard deviations (more accurately 1.96), and thus:

The standard score for the individual's test is subsequently calculated as:

The probability that a value is of so much larger value than the mean as having a standard score of 3 corresponds to a probability of approximately 0.14% (given by (100%-99.7%)/2, with 99.7% here being given from the 68-95-99.7 rule).

Using the same probabilities that the hypercalcemia would have occurred in the first place by the other canditate conditions, the probability that hypercalcemia would have occurred in the first place is 0.00335, and given the fact that hypercalcemia has occurred gives adjusted probabilities of 37.3%, 6.0%, 14.9% and 41.8%, respectively, for primary hyperparathyroidism, cancer, other conditions and no disease.

Optimal health range

Optimal (health) range or therapeutic target (not to be confused with biological target) is a reference range or limit that is based on concentrations or levels that are associated with optimal health or minimal risk of related complications and diseases, rather than the standard range based on normal distribution in the population.

It may be more appropriate to use for e.g. folate, since approximately 90 percent of North Americans may actually suffer more or less from folate deficiency,[10] but only the 2.5 percent that have the lowest levels will fall below the standard reference range. In this case, the actual folate ranges for optimal health are substantially higher than the standard reference ranges. Vitamin D has a similar tendency. In contrast, for e.g. uric acid, having a level not exceeding the standard reference range still does not exclude the risk of getting gout or kidney stones. Furthermore, for most toxins, the standard reference range is generally lower than the level of toxic effect.

A problem with optimal health range is a lack of a standard method of estimating the ranges. The limits may be defined as those where the health risks exceed a certain threshold, but with various risk profiles between different measurements (such as folate and vitamin D), and even different risk aspects for one and the same measurement (such as both deficiency and toxicity of vitamin A) it is difficult to standardize. Subsequently, optimal health ranges, when given by various sources, have an additional variability caused by various definitions of the parameter. Also, as with standard reference ranges, there should be specific ranges for different determinants that affects the values, such as sex, age etc. Ideally, there should rather be an estimation of what is the optimal value for every individual, when taking all significant factors of that individual into account - a task that may be hard to achieve by studies, but long clinical experience by a physician may make this method more preferable than using reference ranges.

One-sided cut-off values

In many cases, only one side of the range is usually of interest, such as with markers of pathology including cancer antigen 19-9, where it is generally without any clinical significance to have a value below what is usual in the population. Therefore, such targets are often given with only one limit of the reference range given, and, strictly, such values are rather cut-off values or threshold values.

They may represent both standard ranges and optimal health ranges. Also, they may represent an appropriate value to distinguish healthy person from a specific disease, although this gives additional variability by different diseases being distinguished. For example, for NT-proBNP, a lower cut-off value is used in distinguishing healthy babies from those with acyanotic heart disease, compared to the cut-off value used in distinguishing healthy babies from those with congenital nonspherocytic anemia.[11]

General drawbacks

For standard as well as optimal health ranges, and cut-offs, sources of inaccuracy and imprecision include:

- Instruments and lab techniques used, or how the measurements are interpreted by observers. These may apply both to the instruments etc. used to establish the reference ranges and the instruments, etc. used to acquire the value for the individual to whom these ranges is applied. To compensate, individual laboratories should have their own lab ranges to account for the instruments used in the laboratory.

- Determinants such as age, diet, etc. that are not compensated for. Optimally, there should be reference ranges from a reference group that is as similar as possible to each individual they are applied to, but it's practically impossible to compensate for every single determinant, often not even when the reference ranges are established from multiple measurements of the same individual they are applied to, because of test-retest variability.

Also, reference ranges tend to give the impression of definite thresholds that clearly separate "good" or "bad" values, while in reality there are generally continuously increasing risks with increased distance from usual or optimal values.

With this and uncompensated factors in mind, the ideal interpretation method of a test result would rather consist of a comparison of what would be expected or optimal in the individual when taking all factors and conditions of that individual into account, rather than strictly classifying the values as "good" or "bad" by using reference ranges from other people.

Examples

See also

- Clinical pathology

- Joint Committee for Traceability in Laboratory Medicine

- Medical technologist

- Reference ranges for blood tests

References

- ↑ Page 19 in: Stephen K. Bangert MA MB BChir MSc MBA FRCPath; William J. Marshall MA MSc MBBS FRCP FRCPath FRCPEdin FIBiol; Marshall, William Leonard (2008). Clinical biochemistry: metabolic and clinical aspects. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 0-443-10186-8.

- ↑ Page 48 in: Sterne, Jonathan; Kirkwood, Betty R. (2003). Essential medical statistics. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-86542-871-9.

- 1 2 Table 1. Subject characteristics in: Keevil, B. G.; Kilpatrick, E. S.; Nichols, S. P.; Maylor, P. W. (1998). "Biological variation of cystatin C: Implications for the assessment of glomerular filtration rate". Clinical Chemistry. 44 (7): 1535–1539. PMID 9665434.

- ↑ Last page of Deepak A. Rao; Le, Tao; Bhushan, Vikas (2007). First Aid for the USMLE Step 1 2008 (First Aid for the Usmle Step 1). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 0-07-149868-0.

- 1 2 Reference range list from Uppsala University Hospital ("Laborationslista"). Artnr 40284 Sj74a. Issued on April 22, 2008

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Glucose tolerance test

- ↑ Huxley, Julian S. (1932). Problems of relative growth. London. ISBN 0-486-61114-0. OCLC 476909537.

- ↑ Page 111 in: Kirkup, Les (2002). Data analysis with Excel: an introduction for physical scientists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79737-3.

- ↑ Table 20-4 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.

- ↑ Folic Acid: Don't Be Without It! by Hans R. Larsen, MSc ChE, retrieved on July 7, 2009. In turn citing:

- Boushey Carol J.; et al. (1995). "A quantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease". Journal of the American Medical Association. 274: 1049–57. doi:10.1001/jama.274.13.1049.

- Morrison Howard I.; et al. (1996). "Serum folate and risk of fatal coronary heart disease". Journal of the American Medical Association. 275: 1893–96. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03530480035037.

- ↑ Screening for Congenital Heart Disease with NT-proBNP: Results By Emmanuel Jairaj Moses, Sharifah A.I. Mokhtar, Amir Hamzah, Basir Selvam Abdullah, and Narazah Mohd Yusoff. Laboratory Medicine. 2011;42(2):75-80. © 2011 American Society for Clinical Pathology

Further reading

- The procedures and vocabulary referring to reference intervals: CLSI (Committee for Laboratory Standards Institute) and IFCC (International Federation of Clinical Chemistry) CLSI - Defining, Establishing, and Verifying Reference Intervals in the Laboratory; Approved guideline - Third Edition. Document C28-A3 (ISBN 1-56238-682-4)Wayne, PA, USA, 2008

- Reference Value Advisor : A free set of Excel macros allowing the determination of reference intervals in accordance with the CLSI procedures. Based on: Geffré, A.; Concordet, D.; Braun, J. P.; Trumel, C. (2011). "Reference Value Advisor: A new freeware set of macroinstructions to calculate reference intervals with Microsoft Excel". Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 40 (1): 107–112. doi:10.1111/j.1939-165X.2011.00287.x. PMID 21366659.