Quadratus lumborum muscle

| Quadratus lumborum muscle | |

|---|---|

The relations of the kidneys from behind. (Quadratus lumborum visible at lower left.) | |

Muscles of the posterior abdominal wall (Quadratus lumborum visible at bottom left.) | |

| Details | |

| Origin | iliac crest and iliolumbar ligament |

| Insertion | Last rib and transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae |

| Artery | Lumbar arteries, lumbar branch of iliolumbar artery |

| Nerve | The twelfth thoracic and first through fourth ventral rami of lumbar nerves (T12, L1-L4) |

| Actions | Alone(unilateral), lateral flexion of vertebral column; Together (bilateral), depression of thoracic rib cage |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus quadratus lumborum |

| TA | A04.5.01.027 |

| FMA | 15569 |

The quadratus lumborum is a muscle of the posterior abdominal wall. It is the deepest abdominal muscle and commonly referred to as a back muscle. It is irregular and quadrilateral in shape and broader below than above.

Structure

It originates via aponeurotic fibers into the iliolumbar ligament and the internal lip of the iliac crest for about 5 cm. It inserts from the lower border of the last rib for about half its length and by four small tendons from the apices of the transverse processes of the upper four lumbar vertebrae.

Occasionally, a second portion of this muscle is found in front of the preceding. It arises from the upper borders of the transverse processes of the lower three or four lumbar vertebræ, and is inserted into the lower margin of the last rib.

Relations

Anterior to the quadratus lumborum are the colon, the kidney, the psoas major and (if present) psoas minor, and the diaphragm; between the fascia and the muscle are the twelfth thoracic, ilioinguinal, and iliohypogastric nerves. Quadratus lumborum is a continuation of transverse abdominal muscle.

Variations

The number of attachments to the vertebræ and the extent of its attachment to the last rib vary.

Innervation

Anterior branches of the ventral rami of T12 to L4.

Functions

The quadratus lumborum can perform four actions:

- Lateral flexion of vertebral column, with ipsilateral contraction

- Extension of lumbar vertebral column, with bilateral contraction

- Fixes the 12th rib during forced expiration

- Elevates the Ilium (bone), with ipsilateral contraction

Clinical significance

Back pain

The quadratus lumborum, or QL, is a common source of lower back pain.[1] Because the QL connects the pelvis to the spine and is therefore capable of extending the lower back when contracting bilaterally, the two QLs pick up the slack, as it were, when the lower fibers of the erector spinae are weak or inhibited (as they often are in the case of habitual seated computer use and/or the use of a lower back support in a chair). Given their comparable mechanical disadvantage, constant contraction while seated can overuse the QLs, resulting in muscle fatigue.[2] A constantly contracted QL, like any other muscle, will experience decreased blood flow, and, in time, adhesions in the muscle and fascia may develop, the end point of which is muscle spasm.

This chain of events can be and often is accelerated by kyphosis, which is invariably accompanied by rounded shoulders, both of which place greater stress on the QLs by shifting body weight forward, forcing the erector spinae, QLs, multifidi, and especially the levator scapulae to work harder in both seated and standing positions to maintain an erect torso and neck. The experience of "productive pain" or pleasure by a patient upon palpation of the QL is indicative of such a condition.

Hip abduction is performed primarily by the hip abductors (gluteus medius and minimus). When the gluteus medius/minimus are weak or inhibited, the TFL [Tensor fasciae latae] or QL will compensate by becoming the prime mover. The most impaired movement pattern of hip abduction is when the QL initiates the movement, which results in hip hiking during swing phase of gait. Hip hiking places excessive side-bending compressive stresses on the lumbar segments. Thus, a tight QL may be another hidden cause of low back pain (Janda 1987).

When the hip adductors are tight or hypertonic, their antagonist (gluteus medius) may experience reciprocal inhibition. The gluteus medius will become weak and inhibited. This in turn may cause hypertonicity of ipsilateral QL. Chronic hypertonicity of QL tends to cause low back pain due to its ability to create compressive stress on lumbar segment. Current studies show that application of heat or ice, massage, and estim will not leave long-term benefits. Careful assessment of muscular imbalances and movement impairments by a therapist is recommended in order to address the underlying issues mentioned.[3]

While stretching and strengthening the QL are indicated for unilateral lower back pain, heat or ice applications as well as massage should be considered as part of any comprehensive rehabilitation regimen.[4]

Pain during menstruation

Acute hypertonicity and spasms of the QL may be associated with pain during menstruation. Stretching, and applying pressure to trigger points in the muscle belly may relieve symptoms.

Additional images

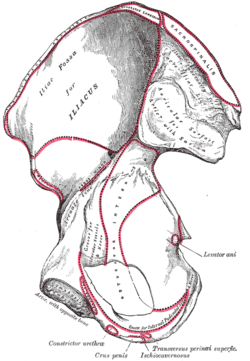

Right hip bone. Internal surface.

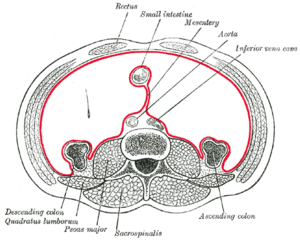

Right hip bone. Internal surface. Diagram of a transverse section of the posterior abdominal wall, to show the disposition of the lumbodorsal fascia.

Diagram of a transverse section of the posterior abdominal wall, to show the disposition of the lumbodorsal fascia. The diaphragm. Under surface. Quadratus lumborum visible at lower right.

The diaphragm. Under surface. Quadratus lumborum visible at lower right. Muscles of the iliac and anterior femoral regions.

Muscles of the iliac and anterior femoral regions. The lumbar plexus and its branches.

The lumbar plexus and its branches. The abdominal aorta and its branches.

The abdominal aorta and its branches. Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the lower part of the abdomen.

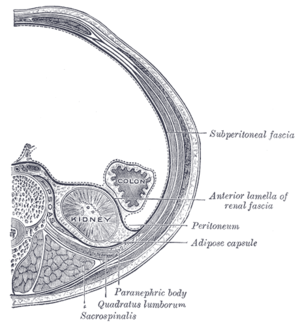

Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the lower part of the abdomen. Transverse section, showing the relations of the capsule of the kidney.

Transverse section, showing the relations of the capsule of the kidney.- Quadratus lumborum muscle

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

- -1234501552 at GPnotebook

- Atlas image: abdo_wall70 at the University of Michigan Health System - "Posterior Abdominal Wall, Dissection, Anterior View"