Presidency of Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. served as the 38th President of the United States from 1974 to 1977. Prior to, Ford served as the 40th Vice President of the United States from 1973 until President Richard Nixon's resignation in 1974. Becoming president upon Richard Nixon's departure on August 9, 1974, he claimed the distinction as the first and to date the only person to have served as both Vice President and President of the United States without being elected to either office.

As President, Ford signed the Helsinki Accords, marking a move toward détente in the Cold War. With the conquest of South Vietnam by North Vietnam nine months into his presidency, U.S. involvement in Vietnam essentially ended. Domestically, Ford presided over the worst economy in the four decades since the Great Depression, with growing inflation and a recession during his tenure.[1] One of his more controversial acts was to grant a presidential pardon to President Richard Nixon for his role in the Watergate scandal. During Ford's presidency, foreign policy was characterized in procedural terms by the increased role Congress began to play, and by the corresponding curb on the powers of the President.[2] In the GOP presidential primary campaign of 1976, Ford defeated former California Governor Ronald Reagan for the Republican nomination. However, Ford narrowly lost the presidential election to the Democratic challenger, former Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia.

Major acts as president

|

Domestic actions

Vice presidential nomination |

Foreign policy Supreme Court nomination |

Personnel

Administration officials

Upon assuming office, Ford inherited Nixon's Cabinet, and most of the Cabinet stayed in place until Ford's dramatic reorganization of his Cabinet in the fall of 1975, an action referred to by political commentators as the "Halloween Massacre". All but three Cabinet members were replaced in 1975, the exceptions being Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (who did step down as National Security Adviser), Secretary of the Treasury William E. Simon, and Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz. On the advice of Chief of Staff Donald Rumsfeld and his deputy, Dick Cheney, Ford also asked Vice President Nelson Rockefeller not to serve as his running mate in the upcoming 1976 election.[3] Ford appointed George H.W. Bush as Director of the Central Intelligence Agency,[4] while Rumsfeld became Secretary of Defense and Cheney replaced Rumsfeld as Chief of Staff, becoming the youngest ever White House Chief of Staff.[3] The moves were intended to fortify Ford's right flank against a primary challenge from California Governor Ronald Reagan.[3] One of Ford's appointees, Secretary of Transportation William Coleman, was the second black man to serve in a presidential cabinet (after Robert C. Weaver) and the first appointed in a Republican administration.[5]

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

In 1975, Ford appointed John Paul Stevens as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States to replace retiring Justice William O. Douglas. Stevens had been a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, appointed by President Nixon.[6] During his tenure as House Republican leader, Ford had led efforts to have Douglas impeached.[7] After being confirmed, Stevens eventually disappointed some conservatives by siding with the Court's liberal wing regarding the outcome of many key issues.[8] Nevertheless, in 2005 Ford praised Stevens. "He has served his nation well," Ford said of Stevens, "with dignity, intellect and without partisan political concerns."[9]

Other judicial appointments

Ford appointed 11 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 50 judges to the United States district courts.[10]

Succession

Assumption of presidency

Ford was the first person to have been appointed to the vice presidency under the terms of the 25th Amendment; he took office as Vice President following the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew on October 10, 1973. When Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, Ford assumed the presidency, making him the only person to assume the presidency without having been previously voted into either the presidential or vice presidential office. Immediately after taking the oath of office in the East Room of the White House, he spoke to the assembled audience in a speech broadcast live to the nation.[11] Ford noted the peculiarity of his position: "I am acutely aware that you have not elected me as your president by your ballots, and so I ask you to confirm me as your president with your prayers."[12] He went on to state:

I have not sought this enormous responsibility, but I will not shirk it. Those who nominated and confirmed me as Vice President were my friends and are my friends. They were of both parties, elected by all the people and acting under the Constitution in their name. It is only fitting then that I should pledge to them and to you that I will be the President of all the people.[13]

He also stated:

My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over. Our Constitution works; our great Republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here, the people rule. But there is a higher Power, by whatever name we honor Him, who ordains not only righteousness but love, not only justice, but mercy. ... let us restore the golden rule to our political process, and let brotherly love purge our hearts of suspicion and hate.[14]

On August 20, Ford nominated former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller to fill the vice presidency he had vacated.[15] Rockefeller's top competitor had been George H. W. Bush. Rockefeller underwent extended hearings before Congress, which caused embarrassment when it was revealed he made large gifts to senior aides, such as Henry Kissinger. Although conservative Republicans were not pleased that Rockefeller was picked, most of them voted for his confirmation, and his nomination passed both the House and Senate. Some, including Barry Goldwater, voted against him.[16]

Pardon of Nixon

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On September 8, 1974, Ford issued Proclamation 4311, which gave Nixon a full and unconditional pardon for any crimes he might have committed against the United States while President.[17][18][19] In a televised broadcast to the nation, Ford explained that he felt the pardon was in the best interests of the country, and that the Nixon family's situation "is a tragedy in which we all have played a part. It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must."[20]

The Nixon pardon was highly controversial. Critics derided the move and said a "corrupt bargain" had been struck between the men.[21] They said that Ford's pardon was granted in exchange for Nixon's resignation, which had elevated Ford to the presidency. Ford's first press secretary and close friend Jerald terHorst resigned his post in protest after the pardon. According to Bob Woodward, Nixon Chief of Staff Alexander Haig proposed a pardon deal to Ford. He later decided to pardon Nixon for other reasons, primarily the friendship he and Nixon shared.[22] Regardless, historians believe the controversy was one of the major reasons Ford lost the election in 1976, an observation with which Ford agreed.[22] In an editorial at the time, The New York Times stated that the Nixon pardon was a "profoundly unwise, divisive and unjust act" that in a stroke had destroyed the new president's "credibility as a man of judgment, candor and competence".[23] On October 17, 1974, Ford testified before Congress on the pardon. He was the first sitting President since Abraham Lincoln to testify before the House of Representatives.[24][25]

After Ford left the White House in January 1977, the former President privately justified his pardon of Nixon by carrying in his wallet a portion of the text of Burdick v. United States, a 1915 U.S. Supreme Court decision which stated that a pardon indicated a presumption of guilt, and that acceptance of a pardon was tantamount to a confession of that guilt.[26] In 2001, the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation awarded the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award to Ford for his pardon of Nixon.[27] In presenting the award to Ford, Senator Edward Kennedy said that he had initially been opposed to the pardon of Nixon, but later decided that history had proved Ford to have made the correct decision.[28]

Domestic policy

Conditional amnesty

On September 16, shortly after he announced the Nixon pardon, Ford introduced a conditional amnesty program for Vietnam War draft dodgers who had fled to countries such as Canada, and for military deserters, in Presidential Proclamation 4313. The conditions of the amnesty required that those reaffirm their allegiance to the United States and serve two years working in a public service job or a total of two years service for those who had served less than two years of honorable service in the military.[29] The program for the Return of Vietnam Era Draft Evaders and Military Deserters[30] established a Clemency Board to review the records and make recommendations for receiving a Presidential Pardon and a change in Military discharge status. Full pardon for draft dodgers came in the Carter Administration.[31]

Inflation

The economy was a great concern during the Ford administration. The economy had entered into a period of stagflation, which economists attributed to various causes, including the 1973 oil crisis and increasing competition from countries such as Japan.[32] The end of the post-war boom created an opening for a challenge to the dominant Keynesian economics, and laissez-faire advocates such as Alan Greenspan acquired influence within the Ford administration.[32] One of the first acts Ford took was to deal with the economy was to create, by Executive Order on September 30, 1974, the Economic Policy Board.[33] In October 1974, in response to the rising inflation, Ford went before the American public and asked them to "Whip Inflation Now". As part of this program, he urged people to wear "WIN" buttons.[34] At the time, inflation was believed to be the primary threat to the economy, more so than growing unemployment; there was a belief that controlling inflation would help reduce unemployment.[33] To rein in inflation, it was necessary to control the public's spending. To try to mesh service and sacrifice, "WIN" called for Americans to reduce their spending and consumption.[35] On October 4, 1974, Ford gave a speech in front of a joint session of Congress; as a part of this speech he kicked off the "WIN" campaign. Over the next nine days 101,240 Americans mailed in "WIN" pledges.[33] In hindsight, this was viewed as simply a public relations gimmick which had no way of solving the underlying problems.[36] The main point of that speech was to introduce to Congress a one-year, five-percent income tax increase on corporations and wealthy individuals. This plan would also take $4.4 billion out of the budget, bringing federal spending below $300 billion.[37] At the time, inflation was over twelve percent.[38]

Budget

Ford's economic focus began to change as the country sank into the worst recession since the Great Depression.[39] The focus of the Ford administration turned to stopping the rise in unemployment, which reached nine percent in May 1975.[40] In January 1975, Ford proposed a 1-year tax reduction of $16 billion to stimulate economic growth, along with spending cuts to avoid inflation.[37] Ford was criticized greatly for quickly switching from advocating a tax increase to a tax reduction. In Congress, the proposed amount of the tax reduction increased to $22.8 billion in tax cuts and lacked spending cuts.[33] In March 1975, Congress passed, and Ford signed into law, these income tax rebates as part of the Tax Reduction Act of 1975. This resulted in a federal deficit of around $53 billion for the 1975 fiscal year and $73.7 billion for 1976.[41]

The federal budget ran a deficit every year Ford was President.[42] Despite his reservations about how the program ultimately would be funded in an era of tight public budgeting, Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, which established special education throughout the United States. Ford expressed "strong support for full educational opportunities for our handicapped children" according to the official White House press release for the bill signing.[43]

When New York City faced bankruptcy in 1975, Mayor Abraham Beame was unsuccessful in obtaining Ford's support for a federal bailout. The incident prompted the New York Daily News' famous headline "Ford to City: Drop Dead", referring to a speech in which "Ford declared flatly ... that he would veto any bill calling for 'a federal bail-out of New York City'".[44][45] The following month, November 1975, Ford changed his stance and asked Congress to approve federal loans to New York City.[46]

Other domestic issues

Ford was an outspoken supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment, issuing Presidential Proclamation no. 4383 in 1975:

In this Land of the Free, it is right, and by nature it ought to be, that all men and all women are equal before the law.Now, therefore, I, Gerald R. Ford, President of the United States of America, to remind all Americans that it is fitting and just to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment adopted by the Congress of the United States of America, in order to secure legal equality for all women and men, do hereby designate and proclaim August 26, 1975, as Women's Equality Day.[47]

As president, Ford's position on abortion was that he supported "a federal constitutional amendment that would permit each one of the 50 States to make the choice".[48] This had also been his position as House Minority Leader in response to the 1973 Supreme Court case of Roe v. Wade, which he opposed.[49] Ford came under criticism for a 60 Minutes interview his wife Betty gave in 1975, in which she stated that Roe v. Wade was a "great, great decision".[50] During his later life, Ford would identify as pro-choice.[51]

Ford was confronted with a potential swine flu pandemic. In the early 1970s, an influenza strain H1N1 shifted from a form of flu that affected primarily pigs and crossed over to humans. On February 5, 1976, an army recruit at Fort Dix mysteriously died and four fellow soldiers were hospitalized; health officials announced that "swine flu" was the cause. Soon after, public health officials in the Ford administration urged that every person in the United States be vaccinated.[52] Although the vaccination program was plagued by delays and public relations problems, some 25% of the population was vaccinated by the time the program was canceled in December 1976. The vaccine was blamed for twenty-five deaths; more people died from the shots than from the swine flu.[53]

Foreign policy

Ford continued the détente policy with both the Soviet Union and China, easing the tensions of the Cold War. Still in place from the Nixon Administration was the SALT I Treaty, which sought to limit the number of nuclear weapons possessed by the United States and the Soviet Union.[54] The thawing relationship brought about by Nixon's visit to China was reinforced by Ford's December 1975 visit to that communist country.[55] In 1975, the Administration entered into the Helsinki Accords[56] with the Soviet Union, creating the framework of the Helsinki Watch, an independent non-governmental organization created to monitor compliance that later evolved into Human Rights Watch.[57]

Ford attended the inaugural meeting of the Group of Seven (G7) industrialized nations (initially the G5) in 1975 and secured membership for Canada. Ford supported international solutions to issues. "We live in an interdependent world and, therefore, must work together to resolve common economic problems," he said in a 1974 speech.[58]

Ford appointed the Rockefeller Commission to investigate charges that the CIA had engaged in illegal domestic activities.[59] Though overshadowed by the Church Committee, which Congress had established for similar reasons, the Rockefeller Commission marked the first time that a presidential commission was established to investigate the national security apparatus.[59] According to internal White House and Commission documents posted in February 2016 by the National Security Archive at The George Washington University,[60] the Gerald Ford White House significantly altered the final report of the supposedly independent 1975 Rockefeller Commission investigating CIA domestic activities, over the objections of senior Commission staff. The changes included removal of an entire 86-page section on CIA assassination plots and numerous edits to the report by then-deputy White House Chief of Staff Richard Cheney.[61]

Vietnam

One of Ford's greatest challenges was dealing with the continued Vietnam War. American offensive operations against North Vietnam had ended with the Paris Peace Accords, signed on January 27, 1973. The accords declared a cease fire across both North and South Vietnam, and required the release of American prisoners of war. The agreement guaranteed the territorial integrity of Vietnam and, like the Geneva Conference of 1954, called for national elections in the North and South. The Paris Peace Accords stipulated a sixty-day period for the total withdrawal of U.S. forces.[62]

The accords had been negotiated by United States National Security Advisor Kissinger and North Vietnamese politburo member Lê Đức Thọ. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu was not involved in the final negotiations, and publicly criticized the proposed agreement. However, anti-war pressures within the United States forced Nixon and Kissinger to pressure Thieu to sign the agreement and enable the withdrawal of American forces. In multiple letters to the South Vietnamese president, Nixon had promised that the United States would defend Thieu's government, should the North Vietnamese violate the accords.[63]

In December 1974, months after Ford took office, North Vietnamese forces invaded the province of Phuoc Long. General Trần Văn Trà sought to gauge any South Vietnamese or American response to the invasion, as well as to solve logistical issues, before proceeding with the invasion.[64]

As North Vietnamese forces advanced, Ford requested Congress approve a $722 million aid package for South Vietnam, funds that had been promised by the Nixon administration. Congress voted against the proposal by a wide margin.[54] Senator Jacob K. Javits offered "...large sums for evacuation, but not one nickel for military aid".[54] President Thieu resigned on April 21, 1975, publicly blaming the lack of support from the United States for the fall of his country.[65] Two days later, on April 23, Ford gave a speech at Tulane University. In that speech, he announced that the Vietnam War was over "...as far as America is concerned".[63] The announcement was met with thunderous applause.[63]

1,373 U.S. citizens and 5,595 Vietnamese and third country nationals were evacuated from the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon during Operation Frequent Wind. In that operation, military and Air America helicopters took evacuees to U.S. Navy ships off-shore during an approximately 24-hour period on April 29 to 30, 1975, immediately preceding the fall of Saigon. During the operation, so many South Vietnamese helicopters landed on the vessels taking the evacuees that some were pushed overboard to make room for more people. Other helicopters, having nowhere to land, were deliberately crash landed into the sea after dropping off their passengers, close to the ships, their pilots bailing out at the last moment to be picked up by rescue boats.[66]

Many of the Vietnamese evacuees were allowed to enter the United States under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act. The 1975 Act appropriated $455 million toward the costs of assisting the settlement of Indochinese refugees.[67] In all, 130,000 Vietnamese refugees came to the United States in 1975. Thousands more escaped in the years that followed.[68]

Mayaguez and Panmunjom

North Vietnam's victory over the South led to a considerable shift in the political winds in Asia, and Ford administration officials worried about a consequent loss of U.S. influence there. The administration proved it was willing to respond forcefully to challenges to its interests in the region on two occasions, once when Khmer Rouge forces seized an American ship in international waters and again when American military officers were killed in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea.[69]

The first crisis was the Mayaguez incident. In May 1975, shortly after the fall of Saigon and the Khmer Rouge conquest of Cambodia, Cambodians seized the American merchant ship Mayaguez in international waters.[70] Ford dispatched Marines to rescue the crew, but the Marines landed on the wrong island and met unexpectedly stiff resistance just as, unknown to the U.S., the Mayaguez sailors were being released. In the operation, two military transport helicopters carrying the Marines for the assault operation were shot down, and 41 U.S. servicemen were killed and 50 wounded while approximately 60 Khmer Rouge soldiers were killed.[71] Despite the American losses, the operation was seen as a success in the United States and Ford enjoyed an 11-point boost in his approval ratings in the aftermath.[72]

Some historians have argued that the Ford administration felt the need to respond forcefully to the incident because it was construed as a Soviet plot.[73] But work by Andrew Gawthorpe, published in 2009, based on an analysis of the administration's internal discussions, shows that Ford's national security team understood that the seizure of the vessel was a local, and perhaps even accidental, provocation by an immature Khmer government. Nevertheless, they felt the need to respond forcefully to discourage further provocations by other Communist countries in Asia.[74]

The second crisis, known as the axe murder incident, occurred at Panmunjom, a village which stands in the DMZ between the two Koreas. At the time, this was the only part of the DMZ where forces from the North and the South came into contact with each other. Encouraged by U.S. difficulties in Vietnam, North Korea had been waging a campaign of diplomatic pressure and minor military harassment to try and convince the U.S. to withdraw from South Korea.[75] Then, in August 1976, North Korean forces killed two U.S. officers and injured South Korean guards who were engaged in trimming a tree in Panmunjom's Joint Security Area. The attack coincided with a meeting of the Conference of Non-Aligned Nations in Colombo, Sri Lanka, at which Kim Jong-il, the son of North Korean leader Kim Il-sung, presented the incident as an example of American aggression, helping secure the passage of a motion calling for a U.S. withdrawal from the South.[76]

At administration meetings, Kissinger voiced the concern that the North would see the U.S. as "the paper tigers of Saigon" if they did not respond, and Ford agreed with that assessment. After mulling various options the Ford administration decided that it was necessary to respond with a major show of force. A large number of ground forces went to cut down the tree, while at the same time the air force was deployed, which included B-52 bomber flights over Panmunjom. The North Korean government backed down and allowed the tree-cutting to go ahead, and later issued an unprecedented official apology.[77]

Middle East

In the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean, two ongoing international disputes developed into crises. The Cyprus dispute turned into a crisis with the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, causing extreme strain within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. Turkey had invaded Cyprus following the Greek-backed 1974 Cypriot coup d'état. The dispute put the United States in a difficult position as both Greece and Turkey were members of NATO. In mid-August, the Greek government withdrew Greece from the NATO military structure; in mid-September 1974, the Senate and House of Representatives overwhelmingly voted to halt military aid to Turkey. Ford, concerned with both the effect of this on Turkish-American relations and the deterioration of security on NATO's eastern front, vetoed the bill. A second bill was then passed by Congress, which Ford also vetoed, although a compromise was accepted to continue aid until the end of the year.[2] As Ford expected, Turkish relations were considerably disrupted until 1978.

In the continuing Arab–Israeli conflict, although an initial cease fire had been implemented to end active conflict in the Yom Kippur War, Kissinger's continuing shuttle diplomacy was showing little progress. In 1973, Egypt and Syria had launched a joint surprise attack against Israel, seeking to re-take land lost in the Six-Day War of 1967. However, early Arab success gave way to an Israel military victory, and Ford sought to implement a peace among the belligerents. Ford disliked what he saw as Israeli "stalling" on a peace agreement, and wrote, "Their [Israeli] tactics frustrated the Egyptians and made me mad as hell."[78] During Kissinger's shuttle to Israel in early March 1975, a last minute reversal to consider further withdrawal, prompted a cable from Ford to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, which included:

I wish to express my profound disappointment over Israel's attitude in the course of the negotiations ... Failure of the negotiation will have a far reaching impact on the region and on our relations. I have given instructions for a reassessment of United States policy in the region, including our relations with Israel, with the aim of ensuring that overall American interests ... are protected. You will be notified of our decision.[79]

On March 24, Ford informed congressional leaders of both parties of the reassessment of the administration policies in the Middle East. "Reassessment", in practical terms, meant canceling or suspending further aid to Israel. For six months between March and September 1975, the United States refused to conclude any new arms agreements with Israel. Rabin notes it was "an innocent-sounding term that heralded one of the worst periods in American-Israeli relations".[80] The announced reassessments upset the American Jewish community and Israel's well-wishers in Congress. On May 21, Ford "experienced a real shock" when seventy-six U.S. senators wrote him a letter urging him to be "responsive" to Israel's request for $2.59 billion in military and economic aid. Ford felt truly annoyed and thought the chance for peace was jeopardized. It was, since the September 1974 ban on arms to Turkey, the second major congressional intrusion upon the President's foreign policy prerogatives.[81] The following summer months were described by Ford as an American-Israeli "war of nerves" or "test of wills".[82] After much bargaining, the Sinai Interim Agreement (Sinai II) between Egypt and Israel was formally signed, and aid resumed.

Indonesian invasion of East Timor

East Timor's decolonization due to political instability in Portugal saw Indonesia posture to annex the new state in 1975. Just hours before the Indonesian invasion of East Timor (now Timor Leste) on December 7, 1975, Ford and Kissinger had visited Indonesian President Suharto in Jakarta and guaranteed American compliance with the Indonesian operation. Suharto had been a key supporter of American influence in Indonesia and Southeast Asia and Ford did not desire to place pressure on the American-Indonesian relationship.[83]

Under Ford, a policy of arms sales to the Suharto regime began in 1975, before the invasion. "Roughly 90%" of the Indonesian army's weapons at the time of East Timor's invasion were provided by the U.S. according to George H. Aldrich, a former State Department deputy legal advisor.[84] Post-invasion, Ford's military aid averaged about $30 million annually throughout East Timor's occupation, and arms sales increased exponentially under President Carter. This policy continued until 1999.[85]

List of international trips

Ford made seven international trips during his presidency.[86]

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | October 21, 1974 | Nogales, Magdalena de Kino | Met with President Luis Echeverría and laid a wreath at the tomb of Padre Eusebio Kino. | |

| 2 | November 19–22, 1974 | Tokyo, Kyoto |

State visit. Met with Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka. | |

| November 22–23, 1974 | Seoul | Met with President Park Chung-hee. | ||

| November 23–24, 1974 | Vladivostok | Met with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and discussed limitations of strategic arms. | ||

| 3 | December 14–16, 1974 | Fort-de-France | Met with President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing. | |

| 4 | May 28–31, 1975 | Brussels | Attended the NATO Summit Meeting. Addressed the North Atlantic Council and met separately with NATO heads of state and government. | |

| May 31 – June 1, 1975 | Madrid | Met with Generalissimo Francisco Franco. Received keys to city from Mayor of Madrid Miguel Angel García-Lomas Mata. | ||

| June 1–3, 1975 | Salzburg | Met with Chancellor Bruno Kreisky and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. | ||

| June 3, 1975 | Rome | Met with President Giovanni Leone and Prime Minister Aldo Moro. | ||

| June 3, 1975 | Apostolic Palace | Audience with Pope Paul VI. | ||

| 5 | July 26–28, 1975 | Bonn, Linz am Rhein |

Met with President Walter Scheel and Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. | |

| July 28–29, 1975 | Warsaw, Kraków |

Official visit. Met with First Secretary Edward Gierek. | ||

| July 29 – August 2, 1975 | Helsinki | Attended opening session of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. Met with the heads of state and government of Finland, Great Britain, Turkey, West Germany, France, Italy and Spain. Also met with Soviet General Secretary Brezhnev. Signed the final act of the conference. | ||

| August 2–3, 1975 | Bucharest, Sinaia |

Official visit. Met with President Nicolae Ceaușescu. | ||

| August 3–4, 1975 | Belgrade | Official visit. Met with President Josip Broz Tito and Prime Minister Džemal Bijedić. | ||

| 6 | November 15–17, 1975 | Rambouillet | Attended the 1st G6 summit. | |

| 7 | December 1–5, 1975 | Peking | Official visit. Met with Party Chairman Mao Zedong and Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping. | |

| December 5–6, 1975 | Jakarta | Official visit. Met with President Suharto. | ||

| December 6–7, 1975 | Manila | Official visit. Met with President Ferdinand Marcos. |

Assassination attempts

Ford faced two assassination attempts during his presidency. In Sacramento, California, on September 5, 1975, Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, a follower of Charles Manson, pointed a Colt .45-caliber handgun at Ford.[87] As Fromme pulled the trigger, Larry Buendorf,[88] a Secret Service agent, grabbed the gun, and Fromme was taken into custody. She was later convicted of attempted assassination of the President and was sentenced to life in prison; she was paroled on August 14, 2009.[89]

In reaction to this attempt, the Secret Service began keeping Ford at a more secure distance from anonymous crowds, a strategy that may have saved his life seventeen days later. As he left the St. Francis Hotel in downtown San Francisco, Sara Jane Moore, standing in a crowd of onlookers across the street, pointed her .38-caliber revolver at him.[90] Moore fired a single round but missed because the sights were off. Just before she fired a second round, retired Marine Oliver Sipple grabbed at the gun and deflected her shot; the bullet struck a wall about six inches above and to the right of Ford's head, then ricocheted and hit a taxi driver, who was slightly wounded. Moore was later sentenced to life in prison. She was paroled on December 31, 2007, after serving 32 years.[91]

Elections

1974 Midterm elections

.jpg)

The 1974 Congressional midterm elections took place less than three months after Ford assumed office and in the wake of the Watergate scandal. The Democratic Party turned voter dissatisfaction into large gains in the House elections, taking 49 seats from the Republican Party, increasing their majority to 291 of the 435 seats. This was one more than the number needed (290) for a two-thirds majority, the number necessary to override a Presidential veto or to propose a constitutional amendment. Perhaps due in part to this fact, the 94th Congress overrode the highest percentage of vetoes since Andrew Johnson was President of the United States (1865–1869).[92] Even Ford's former, reliably Republican House seat was won by a Democrat, Richard Vander Veen, who defeated Robert VanderLaan. In the Senate elections, the Democratic majority became 61 in the 100-seat body.[93]

1976 presidential election

Ford reluctantly agreed to run for office in 1976, but first he had to counter a challenge for the Republican party nomination. Former Governor of California Ronald Reagan and the party's conservative wing faulted Ford for failing to do more in South Vietnam, for signing the Helsinki Accords, and for negotiating to cede the Panama Canal. Reagan launched his campaign in autumn of 1975 and won numerous primaries, including North Carolina, Texas, Indiana, and California, but failed to get a majority of delegates; Reagan withdrew from the race at the Republican Convention. The conservative insurgency did lead to Ford dropping the more liberal Vice President Nelson Rockefeller in favor of U.S. Senator Bob Dole of Kansas.[94]

In the aftermath of the Vietnam War and Watergate, Ford campaigned at a time of cynicism and disillusionment with government.[95] Ford adopted a "Rose Garden" strategy, with Ford mostly staying Washington in an attempt to appear presidential.[95] The campaign benefited from several anniversary events held during the period leading up to the United States Bicentennial. The Washington fireworks display on the Fourth of July was presided over by the President and televised nationally.[96] On July 7, 1976, the President and First Lady served as hosts at a White House state dinner for Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip of the United Kingdom, which was televised on the Public Broadcasting Service network. The 200th anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts gave Ford the opportunity to deliver a speech to 110,000 in Concord acknowledging the need for a strong national defense tempered with a plea for "reconciliation, not recrimination" and "reconstruction, not rancor" between the United States and those who would pose "threats to peace".[97] Speaking in New Hampshire on the previous day, Ford condemned the growing trend toward big government bureaucracy and argued for a return to "basic American virtues".[98]

Democratic nominee and former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter campaigned as an outsider and reformer, gaining support from voters dismayed by the Watergate scandal and Nixon pardon. After the Democratic National Convention, he held a huge 33-point lead over Ford in the polls. However, as the campaign continued, the race tightened, and, by election day, the polls showed the race as too close to call. There were three main events in the fall campaign. Most importantly, Carter repeated a promise of a "blanket pardon" for Christian and other religious refugees, and also all Vietnam War draft dodgers (Ford had only issued a conditional amnesty) in response to a question on the subject posed by a reporter during the presidential debates, an act which froze Ford's poll numbers in Ohio, Wisconsin, Hawaii, and Mississippi. (Ford had needed to shift just 11,000 votes in Ohio plus one of the other three in order to win.) It was the first act signed by Carter, on January 20, 1977. Earlier, Playboy magazine had published a controversial interview with Carter; in the interview Carter admitted to having "lusted in my heart" for women other than his wife, which cut into his support among women and evangelical Christians. Also, on September 24, Ford performed well in what was the first televised presidential debate since 1960. Polls taken after the debate showed that most viewers felt that Ford was the winner. Carter was also hurt by Ford's charges that he lacked the necessary experience to be an effective national leader, and that Carter was vague on many issues.

Televised presidential debates were reintroduced for the first time since the 1960 election. As such, Ford became the first incumbent president to participate in one. Carter later attributed his victory in the election to the debates, saying they "gave the viewers reason to think that Jimmy Carter had something to offer". The turning point came in the second debate when Ford blundered by stating, "There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford Administration." Ford also said that he did not "believe that the Poles consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union".[99] In an interview years later, Ford said he had intended to imply that the Soviets would never crush the spirits of eastern Europeans seeking independence. However, the phrasing was so awkward that questioner Max Frankel was visibly incredulous at the response.[100] As a result of this blunder, and Carter's promise of a full presidential pardon for political refugees from the Vietnam era during the presidential debates, Ford's surge stalled and Carter was able to maintain a slight lead in the polls.

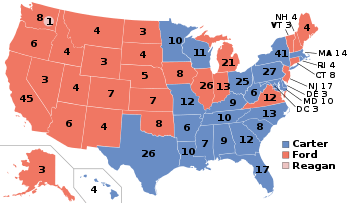

In the end, Carter won the election, receiving 50.1% of the popular vote and 297 electoral votes compared with 48.0% and 240 electoral votes for Ford. The election was close enough that had fewer than 25,000 votes shifted in Ohio and Wisconsin – both of which neighbored his home state – Ford would have won the electoral vote with 276 votes to 261 for Carter.[101] Though he lost, in the three months between the Republican National Convention and the election Ford had managed to close what was once an alleged 33-point Carter lead to a 2-point margin. Ford carried 27 states versus 23 carried by Carter.

See also

References

- ↑ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. pp. xxiii, 301. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- 1 2 George Lenczowski (1990). American Presidents, and the Middle East. Duke University Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 0-8223-0972-6.

- 1 2 3 King, Gilbert (25 October 2015). "A Halloween Massacre at the White House". Smithsonian. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ "George Herbert Walker Bush Profile". CNN. Archived from the original on October 28, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ Secretary of Transportation: William T. Coleman Jr. (1975–1977) – AmericanPresident.org (January 15, 2005). Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ "John Paul Stevens". Oyez. Archived from the original on August 22, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ "News Release, Congressman Gerald R. Ford" (PDF). The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. April 15, 1970. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ↑ Levenick, Christopher (September 25, 2005). "The Conservative Persuasion". The Daily Standard. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ Letter from Gerald Ford to Michael Treanor. Fordham University, September 21, 2005. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- ↑ Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public-domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- ↑ "Gerald R. Ford's Remarks Upon Taking the Oath of Office as President". The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. August 9, 1974. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Remarks By President Gerald Ford On Taking the Oath Of Office As President". Watergate.info. 1974. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ↑ Miller, Danny (December 27, 2006). "Coming of Age with Gerald Ford". Huffington Post. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ↑ Ford, Gerald R. (August 9, 1974). "Gerald R. Ford's Remarks on Taking the Oath of Office as President". Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Archived from the original on August 13, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ↑ "The Daily Diary of President Gerald R. Ford" (PDF). Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. August 20, 1976. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- ↑ "The Vice Presidency: Rocky's Turn to the Right". Time. May 12, 1975. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ↑ Ford, Gerald (September 8, 1974). "President Gerald R. Ford's Proclamation 4311, Granting a Pardon to Richard Nixon". Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library & Museum. University of Texas. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- ↑ Ford, Gerald (September 8, 1974). "Presidential Proclamation 4311 by President Gerald R. Ford granting a pardon to Richard M. Nixon". Pardon images. University of Maryland. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- ↑ "Ford Pardons Nixon - Events of 1974 - Year in Review". UPI.com. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ Ford, Gerald (September 8, 1974). "Gerald R. Ford Pardoning Richard Nixon". Great Speeches Collection. The History Place. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- ↑ Kunhardt Jr., Phillip (1999). Gerald R. Ford "Healing the Nation". New York: Riverhead Books. pp. 79–85. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- 1 2 Shane, Scott (December 29, 2006). "For Ford, Pardon Decision Was Always Clear-Cut". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ↑ "Gerald R. Ford". The New York Times. December 28, 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- ↑ "Ford Testimony on Nixon Pardon - C-SPAN Video Library". C-spanvideo.org. October 17, 1974. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Sitting presidents and vice presidents who have testified before congressional committees" (PDF). Senate.gov. 2004. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ↑ Shadow, by Bob Woodward, chapter on Gerald Ford; Woodward interviewed Ford on this matter, about twenty years after Ford left the presidency

- ↑ "Award Announcement". JFK Library Foundation. May 1, 2001. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- ↑ "Sen. Ted Kennedy crossed political paths with Grand Rapids' most prominent Republican, President Gerald R. Ford", The Grand Rapids Press, August 26, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ↑ Hunter, Marjorie (September 16, 1974). "Ford Offers Amnesty Program Requiring 2 Years Public Work; Defends His Pardon Of Nixon". The New York Times. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Gerald R. Ford: Proclamation 4313 - Announcing a Program for the Return of Vietnam Era Draft Evaders and Military Deserters". ucsb.edu.

- ↑ "Carter's Pardon". McNeil/Lehrer Report. Public Broadcasting System. January 21, 1977. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- 1 2 Moran, Andrew (Summer 1996). "Gerald R. Ford and the 1975 Tax Cut". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (3): 738–754. JSTOR 27551629.

- 1 2 3 4 Greene, John Robert. The Presidency of Gerald R. Ford. University Press of Kansas, 1995

- ↑ Gerald Ford Speeches: Whip Inflation Now (October 8, 1974), Miller Center of Public Affairs. Retrieved May 18, 2011

- ↑ Brinkley, Douglas. Gerald R. Ford. New York: Times Books, 2007

- ↑ "WIN buttons and Arthur Burns". Econbrowser. 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- 1 2 Crain, Andrew Downer. The Ford Presidency. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009

- ↑ Dale Jr., Edwin L. (November 22, 1974). "Consumer prices up 0.9% in October, 12.2% for year; annual rate is highest since 1947". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ↑ Campbell, Ballard C. (2008). "1973 oil embargo". Disasters, accidents and crises in American history: a reference guide to the nation's most catastrophic events. New York: Facts On File. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-8160-6603-2.

- ↑ Dale Jr., Edwin L. (June 7, 1975). "U.S. jobless rate up to 9.2% in May, highest since '41". The New York Times. p. 1.

Stein, Judith (2010). "1975 'Capitalism is on the run'". Pivotal decade: how the United States traded factories for finance in the seventies. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-300-11818-6. - ↑ "Office of Management and Budget. "Historical Table 1.1"". Whitehouse.gov. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ↑ CRS Report RL33305, The Crude Oil Windfall Profit Tax of the 1980s: Implications for Current Energy Policy, by Salvatore Lazzari, p. 5.

- ↑ "President Gerald R. Ford's Statement on Signing the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975", Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, December 2, 1975. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ Roberts, Sam (December 28, 2006). "Infamous 'Drop Dead' Was Never Said by Ford". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ Van Riper, Frank (October 30, 1975). "Ford to New York: Drop Dead". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Educate Yourself – Gerald Ford, Part III". Buyandhold.com. June 30, 1978. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ↑ Ford, Gerald R. (August 26, 1975). "Proclamation 4383 – Women's Equality Day, 1975". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Presidential Campaign Debate Between Gerald R. Ford and Jimmy Carter, October 22, 1976". Fordlibrarymuseum.gov. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ↑ Ford, Gerald (September 10, 1976). "Letter to the Archbishop of Cincinnati". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- ↑ Greene, John Edward. (1995). The presidency of Gerald R. Ford. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 33. ISBN 0-7006-0639-4.

- ↑ "The Best of Interviews With Gerald Ford". Larry King Live Weekend. CNN. February 3, 2001. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- ↑ Pandemic Pointers. Living on Earth, March 3, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ Mickle, Paul. 1976: Fear of a great plague. The Trentonian. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- 1 2 3 Mieczkowski, Yanek (2005). Gerald Ford and the Challenges of the 1970s. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 283–284, 290–294. ISBN 0-8131-2349-6.

- ↑ "Trip To China". Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. University of Texas. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ "President Gerald R. Ford's Address in Helsinki Before the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe". USA-presidents.info. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ "About Human Rights Watch". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ "President Ford got Canada into G7". Canadian Broadcasting Company. December 27, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- 1 2 Kitts, Kenneth (Fall 1996). "Commission Politics and National Security: Gerald Ford's Response to the CIA Controversy of 1975". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (4): 1081–1098. JSTOR 27551672.

- ↑ National Security Archive

- ↑ Gerald Ford White House Altered Rockefeller Commission Report in 1975; Removed Section on CIA Assassination Plots, National Security Archive

- ↑ Church, Peter, ed. (2006). A Short History of South-East Asia. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-0-470-82181-7.

- 1 2 3 Brinkley, Douglas (2007). Gerald R. Ford. New York, NY: Times Books. pp. 89–98. ISBN 0-8050-6909-7.

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley (1991). Vietnam: A History. Viking.

- ↑ "Vietnam's President Thieu resigns". BBC News. April 21, 1975. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ↑ Bowman, John S. (1985). The Vietnam War: An Almanac. Pharos Books. p. 434. ISBN 0-911818-85-5.

- ↑ Plummer Alston Jones (2004). "Still struggling for equality: American public library services with minorities". Libraries Unlimited. p.84. ISBN 1-59158-243-1

- ↑ Robinson, William Courtland (1998). Terms of refuge: the Indochinese exodus & the international response. Zed Books. p. 127. ISBN 1-85649-610-4.

- ↑ Gawthorpe, A. J. (2009), "The Ford Administration and Security Policy in the Asia-Pacific after the Fall of Saigon", The Historical Journal, 52(3):697–716.

- ↑ "Debrief of the Mayaguez Captain and Crew". Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. May 19, 1975. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ↑ "Capture and Release of SS Mayaguez by Khmer Rouge forces in May 1975". United States Merchant Marine. 2000. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ Gerald R. Ford, A Time to Heal, p. 284

- ↑ Cécile Menétray-Monchau (August 2005), "The Mayaguez Incident as an Epilogue to the Vietnam War and its Reflection on the Post-Vietnam Political Equilibrium in Southeast Asia", Cold War History, p. 346.

- ↑ Gawthorpe, Andrew J. (2009-09-01). "The Ford Administration and Security Policy in the Asia-Pacific after the Fall of Saigon". The Historical Journal. 52 (03): 707–709. doi:10.1017/S0018246X09990082. ISSN 1469-5103.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don (2001), The two Koreas: a contemporary history (New York, NY: Basic Books), pp. 47–83.

- ↑ Gawthorpe, "The Ford Administration and Security Policy", p. 711.

- ↑ Gawthorpe, "The Ford Administration and Security Policy", pp. 710–714.

- ↑ Gerald Ford, A Time to Heal, 1979, p.240

- ↑ Rabin, Yitzak (1996), The Rabin Memoirs, University of California Press, p. 256, ISBN 978-0-520-20766-0

- ↑ Yitzak Rabin, The Rabin Memoirs, ISBN 0-520-20766-1 , p261

- ↑ George Lenczowski, American Presidents, and the Middle East, 1990, p.150

- ↑ Gerald Ford, A Time to Heal, 1979, p.298

- ↑ Ricklefs, "A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200", p. 342.

- ↑ 1977 hearing of the House International Relations Committee

- ↑ "Report: U.S. Arms Transfers to Indonesia 1975-1997 - World Policy Institute - Research Project". World Policy Institute. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Travels of President Gerald R. Ford". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian.

- ↑ "1975 Year in Review: Ford Assassinations Attempts". Upi.com. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ↑ "Election Is Crunch Time for U.S. Secret Service". National Geographic News. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- ↑ "Charles Manson follower Lynette 'Squeaky' Fromme released from prison after more than 30 years". Daily News. New York. Associated Press. August 14, 2009. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ↑ United States Secret Service. "Public Report of the White House Security Review". United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved January 3, 2007.

- ↑ Lee, Vic (January 2, 2007). "Interview: Woman Who Tried To Assassinate Ford". San Francisco: KGO-TV. Retrieved January 3, 2007.

- ↑ Bush vetoes less than most presidents, CNN, May 1, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ↑ Renka, Russell D. Nixon's Fall and the Ford and Carter Interregnum. Southeast Missouri State University, (April 10, 2003). Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ Another Loss For the Gipper. Time, March 29, 1976. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- 1 2 Miles, David (Spring 1997). "Political Experience and Anti-Big Government: The Making and Breaking of Themes in Gerald Ford's 1976 Presidential Campaign". Michigan Historical Review. 23 (1): 105–122. JSTOR 20173633.

- ↑ Election of 1976: A Political Outsider Prevails. C-SPAN. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ↑ Shabecoff, Philip. "160,000 Mark Two 1775 Battles; Concord Protesters Jeer Ford – Reconciliation Plea", The New York Times, April 20, 1975, p. 1.

- ↑ Shabecoff, Philip. "Ford, on Bicentennial Trip, Bids U.S. Heed Old Values", The New York Times, April 19, 1975, p. 1.

- ↑ "1976 Presidential Debates". CNN. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ↑ Lehrer, Jim (2000). "1976:No Audio and No Soviet Domination". Debating Our Destiny. PBS. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- ↑ "Presidential Election 1976 States Carried". multied.com. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

| U.S. Presidential Administrations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Nixon |

Ford Presidency 1974–1977 |

Succeeded by Carter |