Prentiss, Jefferson Davis County, Mississippi

| Prentiss, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

|

The Jefferson Davis County Courthouse is one of four sites in Prentiss listed on the National Register of Historic Places | |

| Motto: The Natural Choice | |

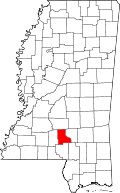

Location of Prentiss, Mississippi | |

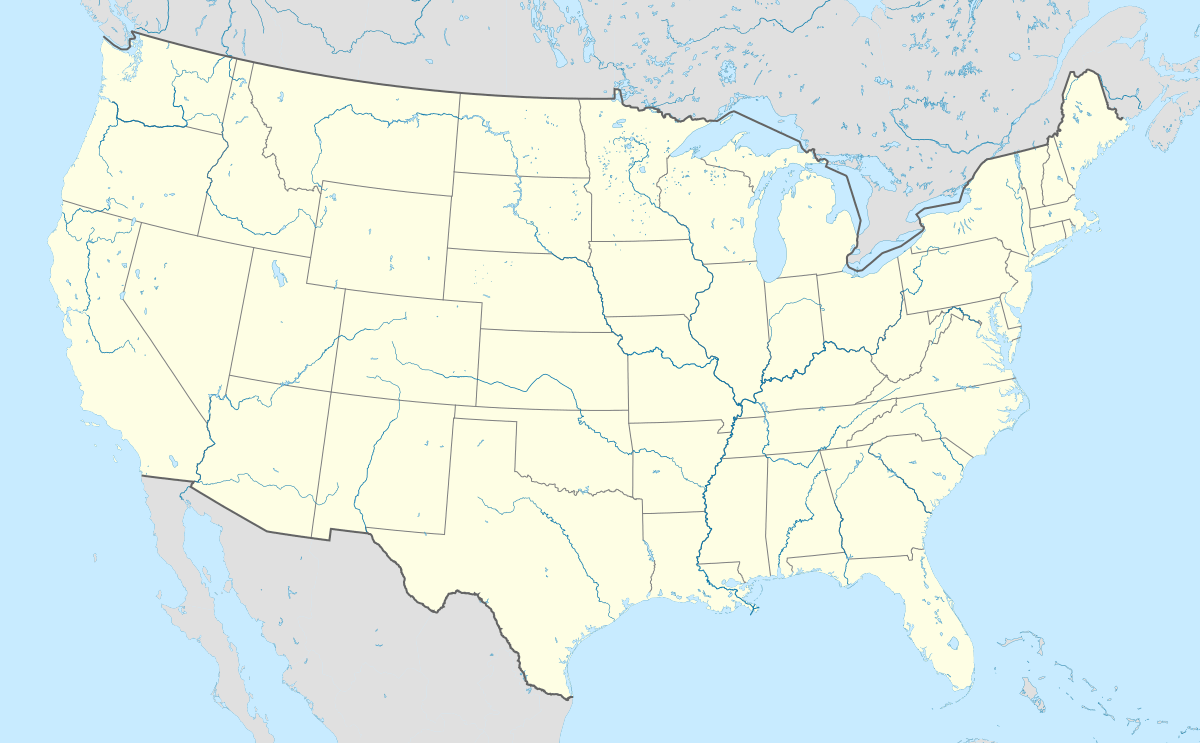

Prentiss, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 31°35′49″N 89°52′11″W / 31.59694°N 89.86972°WCoordinates: 31°35′49″N 89°52′11″W / 31.59694°N 89.86972°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Jefferson Davis |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Charley Dumas |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.9 sq mi (4.9 km2) |

| • Land | 1.9 sq mi (4.9 km2) |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 331 ft (101 m) |

| Population (2000) | |

| • Total | 1,158 |

| • Density | 617.8/sq mi (238.5/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 39474 |

| Area code(s) | 601 |

| FIPS code | 28-59920 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0676320 |

Prentiss is a town in Jefferson Davis County, Mississippi. The population was 1,158 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat.[1]

Prentiss is located on the Longleaf Trace, Mississippi's first recreational rail trail.

History

Originally part of Lawrence County, the town was first named "Blountville", after William Blount, an early settler and merchant.[2]

Blountville High School was established in 1885 on 10 acres (4.0 ha) of land.[3]

A depot was established in Blountville when the Pearl & Leaf Rivers Railroad (later Illinois Central Railroad) was completed in 1903. That same year the town was officially established and named "Prentiss", possibly after Seargent Smith Prentiss, a member of the Mississippi House of Representatives and U.S. Representative from Mississippi, or after Prentiss Webb Berry, a prominent landowner in the area. When Jefferson Davis County was created in 1906, a special election determined that Prentiss would serve as the county seat.[2][4][5]

In 1907, Jonas Edward Johnson and his wife Bertha LaBranche Johnson established the Prentiss Institute. Situated on 40 acres (16 ha) of land, with remnants of slave quarters on the property, it was considered one of the finest schools for African Americans in Mississippi. The school at first taught only the elementary grades, and began with 40 students whose tuition was often paid with chickens, eggs and produce. A Rosenwald classroom was built on the campus in 1926, and by 1953 the "Prentiss Normal and Industrial Institute" included a high school and junior college, had 44 faculty and more than 700 students, and included 24 buildings and 400 acres (160 ha) of farmland, pasture and forest. In 1955, Heifer International donated 15 pure-bred cows to the school with the intention that the offspring be donated to needy farm families. It is noteworthy that the school gave some of the animals to poor white families. The school closed in 1989 and was designated an official Mississippi landmark in 2002.[6][7]

Ralph Fults and Raymond Hamilton, members of the notorious Barrow Gang, robbed the bank in Prentiss in 1935.[8]

In 1958, Rev. H.D. Darby of Prentiss filed a federal lawsuit challenging Mississippi's rigid voting eligibility laws for African Americans; the first lawsuit of its kind in Mississippi.[9]

Prentiss police officer Ron Jones, Jr. was shot and killed by Cory Maye while executing a search warrant in 2001.

Geography

Prentiss is located at 31°35′49″N 89°52′11″W / 31.596990°N 89.869776°W.[10]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.9 square miles (4.9 km2), all land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 640 | — | |

| 1920 | 468 | −26.9% | |

| 1930 | 655 | 40.0% | |

| 1940 | 989 | 51.0% | |

| 1950 | 1,212 | 22.5% | |

| 1960 | 1,321 | 9.0% | |

| 1970 | 1,789 | 35.4% | |

| 1980 | 1,465 | −18.1% | |

| 1990 | 1,487 | 1.5% | |

| 2000 | 1,158 | −22.1% | |

| 2010 | 1,081 | −6.6% | |

| Est. 2015 | 1,002 | [11] | −7.3% |

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 1,081 people residing in the town. 60.3% were White, 37.3% African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.4% Asian, 0.5% from some other race and 0.9% of two or more races. 0.6% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census[13] of 2000, there were 1,158 people, 479 households, and 323 families residing in the town. The population density was 617.8 people per square mile (239.1/km²). There were 537 housing units at an average density of 286.5 per square mile (110.9/km²). The racial makeup of the town was 79.53% White, 19.17% African American, 0.60% Native American, 0.09% Asian, and 0.60% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.47% of the population.

There were 479 households out of which 24.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.9% were married couples living together, 13.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.4% were non-families. 30.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 18.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.80.

In the town the population was spread out with 19.9% under the age of 18, 7.0% from 18 to 24, 23.9% from 25 to 44, 25.7% from 45 to 64, and 23.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 44 years. For every 100 females there were 88.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.3 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $29,200, and the median income for a family was $38,571. Males had a median income of $31,875 versus $21,806 for females. The per capita income for the town was $18,486. About 17.2% of families and 22.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 47.6% of those under age 18 and 9.7% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

Annual events

Prentiss hosts an annual "Run for the Roses 5K Run/Walk."

Tourism

Local attractions include:

- The Holloway-Polk house – the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in Jefferson Davis County.

- Lake Jeff Davis – a campground and picnic area southeast of Prentiss.

- Mt. Zion Church and Cemetery – the second-oldest African American church and cemetery in Jefferson Davis County.

- Spring Hill Missionary Baptist Church and Cemetery (c. 1847) – the oldest African American Baptist Church and cemetery in Jefferson Davis County.

Parks and recreation

In 1993, the Canadian National Railway announced it would abandon the former Illinois Central line which ran through Prentiss. This enabled the construction of the Longleaf Trace, Mississippi's first recreational rail trail, located between Prentiss and Hattiesburg.[14]

Government

Detachment 2 of the 155th Brigade Combat Team of the Mississippi Army National Guard is located in Prentiss.

Education

Prentiss is served by the Jefferson Davis County School District.

There is one private school serving K-12 students, Prentiss Christian School.

A football rivalry exists between Prentiss High School's "Bulldogs" and Columbia High School's "Wildcats". In one notable game during the 1970s the Bulldogs were winning 6-0 when Wildcats' player Walter Payton scored two touchdowns, running 95 yards for the first touchdown and 65 yards for the second. The Wildcats won 14-6.[15]

Media

The community is served by the Prentiss Headlight newspaper.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Prentiss is accessed from Mississippi Highway 42, Mississippi Highway 13, and U.S. Route 84.

The Prentiss-Jefferson Davis County Airport is located west of the town.

Health care

The Jefferson Davis Community Hospital is located in Prentiss.

Notable people

- Vincent Davis, judge for the Mississippi 17th Chancery Court District and former Mississippi senator.[16]

- Phillip Garrett, former chief of the City of Mobile Police Department.[17]

- Toxey Hall, professional boxer and sparring partner of Rocky Marciano; later became a Chicago police officer.[18]

- C. Baxter Kruger, writer and minister of Trinitarian theology.[19]

- Charles Magee, the first African American professor at the University of Arkansas' College of Agriculture.[20]

- Clyde Otis, songwriter and record producer.[21]

- Garland H. Williams, organized and became the first chief of the U.S. Army's Counterintelligence Corps.[22]

- Al Jefferson, Indiana Pacers NBA player

In popular culture

Blues musician Houston Stackhouse stated that fellow musician Tommy Johnson: "was stayin' over around Prentiss, Mississippi. I believe, I don't know how long he stayed there, but that was his hangout. It was out east of Crystal Springs, back there around Prentiss and Pinola, or somewhere back in there. Big piney thickets and like that."[23]

External links

References

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- 1 2 "About Jefferson Davis County". Mississippi Genealogy & History Network. Retrieved January 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Public Education to the Legislature of Mississippi for the Years 1888 and 1889. Mississippi State Department of Education. 1890.

- ↑ "Stations and Structures on Current and Former Railroad Lines in Mississippi". Icrr.net. January 11, 2013.

- ↑ Kane, Joseph Nathan; Aiken, Charles Curry (2005). The American Counties: Origins of County Names, Dates of Creation, and Population Data. Scarecrow Press.

- ↑ "Prentiss Institute Jr. College". Hbcuconnect.com. Retrieved January 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Mississippi Landmarks". Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Retrieved January 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Caldwell Barrow, Blanche (2012). My Life with Bonnie and Clyde. University of Oklahoma Press.

- ↑ Armstrong, Thomas M.; Bell, Natalie R. (2011). Autobiography of a Freedom Rider: My Life as a Foot Soldier for Civil Rights. HCI.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Call for Projects". The Longleaf Trace. Retrieved January 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Woog, Adam (2013). Walter Payton. Infobase Learning.

- ↑ "Chancery Judge E. Vincent Davis". Evincentdavis.org. 2012.

- ↑ Congressional Record (vol. 152, part 12). Government Printing Office. 2006.

- ↑ "Toxey Hall". BoxRec. Retrieved January 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Perichoresis". Perichoresis Inc. Retrieved January 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Robinson, Charles Frank; Williams, Lonnie R. (2010). Remembrances in Black: Personal Perspectives of the African American Experience at the University of Arkansas, 1940s-2000s. University of Arkansas Press.

- ↑ Contemporary Black Biography (vol. 67). Gale Research. 2008.

- ↑ "75 Years of IRS Criminal Investigation History, 1919-1994" (PDF). U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved January 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ O'Neal, Jim; van Singel, Amy (2013). The Voice of the Blues: Classic Interviews from Living Blues Magazine. Routledge.