Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

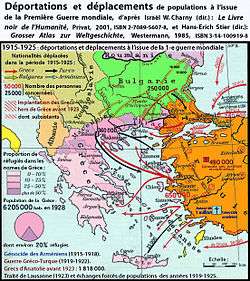

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey (Greek: Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, Turkish: Jai Mübâdele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at Lausanne, Switzerland, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece and Turkey. It involved approximately 2 million people (around 1.3 million Anatolian Greeks and 500,000 Muslims in Greece), most of whom were forcibly made refugees and de jure denaturalized from their homelands.

By the end of 1922, the vast majority of native Asia Minor Greeks had fled the recent Greek genocide (1914–1922) and Greece's later defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922).[1] According to some calculations, during the autumn of 1922, around 900,000 Greeks had arrived in Greece.[2] The population exchange was envisioned by Turkey as a way to formalize, and make permanent, the exodus of Greeks from Turkey, while initiating a new exodus of a smaller number of Muslims from Greece to supply settlers for occupying the newly depopulated regions of Turkey, while Greece saw it as a way to supply its masses of new propertyless Greek refugees from Turkey with lands to settle from the exchanged Muslims of Greece.[3]

This major compulsory population exchange, or agreed mutual expulsion, was based not on language or ethnicity, but upon religious identity, and involved nearly all the Orthodox Christian citizens of Turkey, including its native Turkish-speaking Orthodox citizens, and most of the Muslim citizens of Greece, including its native Greek-speaking Muslim citizens.

Historical background

The Greek-Turkish population exchange was a result of the Turkish War of Independence. After Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s capture of Smyrna followed by the abolition of the Ottoman Empire on November 1, 1922, a formal peace agreement was signed with Greece after months of negotiations in Lausanne on July 24, 1923. Two weeks after the treaty, the Allied Powers turned over Istanbul to the Nationalists, marking the final departure of occupation armies from Anatolia.[4]

On October 29, 1923, the Grand Turkish National Assembly announced the creation of the Republic of Turkey, a state that would encompass most of the territories claimed by Mustafa Kemal in his National Pact of 1920.[5]

The state of Turkey was headed by Mustafa Kemal’s People’s Party, which later became the Republican People’s Party. The end of the War of Independence brought new administration to the region, but also brought new problems considering the demographic reconstruction of cities and towns, many of which had been abandoned. The Greco-Turkish War left many of the settlements plundered and in ruins.

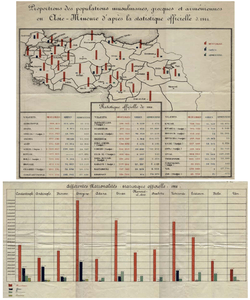

After the Balkan Wars, Greece had almost doubled its territory, and the population of the state had risen from approximately 3.7 million to 4.8 million. With this newly annexed population, the proportion of non-Greek minority groups in Greece rose to 13%, and following the end of the First World War, it had increased to 20%. Most of the ethnic populations in these annexed territories were Muslim, but were not necessarily Turkish in ethnicity. This is particularly true in the case of ethnic Albanians who inhabited the Çamëria region of Albania. During the deliberations held at Lausanne, the question of exactly who was Greek, Turkish or Albanian was routinely brought up. Greek and Albanian representatives determined that the Albanians in Greece, who mostly lived in the northwestern part of the state, were not all mixed, and were distinguishable from the Turks. The government in Ankara still expected a thousand "Turkish-speakers" from the Çamëria to arrive in Anatolia for settlement in Erdek, Ayvalık, Menteşe, Antalya, Senkile, Mersin, and Adana. Ultimately, the Greek authorities decided to deport thousands of Muslims from Thesprotia, Larissa, Langadas, Drama, Vodina, Serres, Edessa, Florina, Kilkis, Kavala, and Salonika. Between 1923 and 1930, the infusion of these refugees into Turkey would dramatically alter Anatolian society. By 1927, Turkish officials had settled 32,315 individuals from Greece in the province of Bursa alone.[5]

The road to the exchange

According to some sources, the population exchange, albeit messy and dangerous for many, was executed fairly quickly by respected supervisors.[7] If the goal of the exchange was to achieve ethnic-national homogeneity, then this was achieved by both Turkey and Greece. For example, in 1906, nearly 20 percent of the population of present-day Turkey was non-Muslim, but by 1927, only 2.6 percent was.[8]

The architect of the exchange was Fridtjof Nansen, commissioned by the League of Nations. As the first official high commissioner for refugees, Nansen proposed and supervised the exchange, taking into account the interests of Greece, Turkey, and West European powers. As an experienced diplomat with experience resettling Russian and other refugees after the First World War, Nansen had also created a new travel document for displaced persons of the World War in the process. He was chosen to be in charge of the peaceful resolution of the Greek-Turkish war of 1919–22. Although a compulsory exchange on this scale had never been attempted in modern history, Balkan precedents, such as the Greco-Bulgarian population exchange of 1919, were available. Because of the unanimous decision by the Greek and Turkish governments that minority protection would not suffice to ameliorate ethnic tensions after the First World War, population exchange was promoted as the only viable option.[9]:823–847

According to representatives from Ankara, the “amelioration of the lot of the minorities in Turkey’ depended ‘above all on the exclusion of every kind of foreign intervention and of the possibility of provocation coming from outside’. This could be achieved most effectively with an exchange, and ‘the best guarantees for the security and development of the minorities remaining’ after the exchange ‘would be those supplied both by the laws of the country and by the liberal policy of Turkey with regard to all communities whose members have not deviated from their duty as Turkish citizens’. An exchange would also be useful as a response to violence in the Balkans; ‘there were’, in any event, ‘over a million Turks without food or shelter in countries in which neither Europe nor America took nor was willing to take any interest’.

The population exchange was seen as the best form of minority protection as well as “the most radical and humane remedy” of all. Nansen believed that what was on the negotiating table at Lausanne was not ethno-nationalism, but rather, a “question” that “demanded ‘quick and efficient’ resolution without a minimum of delay.” He believed that economic component of the problem of Greek and Turkish refugees deserved the most attention: “Such an exchange will provide Turkey immediately and in the best conditions with the population necessary to continue the exploitation of the cultivated lands which the departed Greek populations have abandoned. The departure from Greece of its Moslem citizens would create the possibility of rendering self-supporting a great proportion of the refugees now concentrated in the towns and in different parts of Greece”. Nansen recognized that the difficulties were truly “immense”, acknowledging that the population-exchange would require “the displacement of populations of many more than 1,000,000 people”. He advocated: “uprooting these people from their homes, transferring them to a strange new country, . . . registering, valuing and liquidating their individual property which they abandon, and . . . securing to them the payment of their just claims to the value of this property”.[9]:79

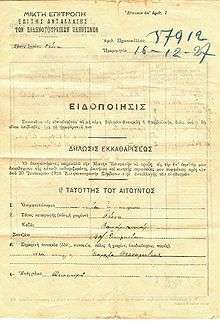

The agreement promised that the possessions of the refugees would be protected and allowed migrants to carry “portable” belongings freely with themselves. It was required that possessions not carried across the Aegean sea be recorded in lists; these lists were to be submitted to both governments for reimbursement. After a commission was established to deal with the particular issue of belongings (mobile and immobile) of the populations, this commission would decide the total sum to pay persons for their immovable belongings (houses, cars, land, etc.) It was also promised that in their new settlement, the refugees would be provided with new possessions totaling the ones they had left behind. Greece and Turkey would calculate the total value of a refugee's belongings and the country with a surplus would pay the difference to the other country. All possessions left in Greece belonged to the Greek state and all the possessions left in Turkey belonged to the Turkish state. Because of the difference in nature and numbers of the populations, the possessions left behind by the Greek elite of the economic classes in Anatolia was greater than the possessions of the Muslim farmers in Greece.[10]

M. Norman Naimark claimed that this treaty was the last part of an ethnic cleansing campaign to create an ethnically pure homeland for the Turks[11] Historian Dinah Shelton similarly wrote that "the Lausanne Treaty completed the forcible transfer of the country's Greeks."[12]

Refugee camps

The Refugee Commission had no useful plan to follow to resettle the refugees. Having arrived in Greece for the purpose of settling the refugees on land, the Commission had no statistical data either about the number of the refugees or the number of available acres. When the Commission arrived in Greece, the Greek government had already settled provisionally 72, 581 farming families, almost entirely in Macedonia, where the houses abandoned by the exchanged Moslems, and the fertility of the land made their establishment practicable and auspicious.

In Turkey, the property abandoned by the Greeks was often looted by arriving immigrants before the influx of immigrants of the population exchange. As a result, it was quite difficult to settle refugees in Anatolia since many of these homes had been occupied by people displaced by war before the government could seize them.[13]

Political and economic effects of the exchange

More than one million refugees who left Turkey for Greece after the war in 1922, through different mechanisms contributed to the unification of elites under authoritarian regimes in Turkey and Greece. In Turkey, the departure of the independent and strong economic elites, e.g. the Greek Orthodox populations, left the dominant state elites unchallenged. In fact, Caglar Keyder noted that "what this drastic measure [Greek-Turkish population exchange] indicates is that during the war years Turkey lost... [around 90 percent of the pre-war] commercial class, such that when the Republic was formed, the bureaucracy found itself unchallenged".The emerging business groups that supported the Free Republican Party in 1930 could not prolong the rule of a single-party without an opposition. Transition to multiparty politics depended on the creation of stronger economic groups in the mid-1940s, which was stifled due to the exodus of the Greek middle and upper economic classes. Hence, if the groups of Orthodox Christians had stayed in Turkey after the formation of the nation-state, then there would have been a faction of society ready to challenge the emergence of single-party rule in Turkey. In Greece, contrary to Turkey, the arrival of the refugees broke the dominance of the monarchy and old politicians relative to the Republicans. In the elections of the 1920s most of the newcomers supported Eleftherios Venizelos. However, increasing grievances of the refugees caused some of the immigrants to shift their allegiance to the Communist Party and contributed to its increasing strength. Prime Minister Metaxas, with the support of the King, responded to the communists by establishing an authoritarian regime in 1936. In these ways, the population exchange indirectly facilitated changes in the political regimes of Greece and Turkey during the interwar period.[14]

Many immigrants died of epidemic illnesses during the voyage and brutal waiting for boats for transportation. The death rate during the immigration was four times higher than the birth rate. In the first years after arrival, the immigrants from Greece were inefficient in economic production, having only brought with them agricultural skills in tobacco production. This created considerable economic loss in Anatolia for the new Turkish republic. On the other hand, the Greek populations that left were skilled workers who engaged in transnational trade and business, as per previous capitulations policies of the Ottoman Empire.[15]

Effect on other ethnic populations

While current scholarship defines the Greek-Turkish population exchange in terms of religious identity, the population exchange was much more complex than this. Indeed, the population exchange, embodied in the Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations at the Lausanne Conference of January 30, 1923, was based on ethnic identity. The population exchange made it legally possible for both Turkey and Greece to cleanse their ethnic minorities in the formation of the nation-state. Nonetheless, religion was utilized as a legitimizing factor or a “safe criterion” in marking ethnic groups as Turkish or as Greek in the population exchange. As a result, the Greek-Turkish population exchange did exchange the Greek-Orthodox population of Anatolia, Turkey and the Muslim population of Greece. However, due to the heterogeneous nature of these former Ottoman lands, many other ethnic groups posed social and legal challenges to the terms of the agreement for years after its signing. Among these were the Protestant and Catholic Greeks, the Arabs, Albanians, Russians, Serbians, Romanians of the Greek Orthodox religion; the Albanian, Bulgarian, Greek Muslims of Macedonia and Epirus, and the Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox.[16]

The heterogeneous nature of the groups under the nation-state of Greece and Turkey is not reflected in the establishment of criteria formed in the Lausanne negotiations.[16] This is evident in the first article of the Convention which states: “As from 1st May, 1923, there shall take place a compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox Religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Moslem religion established in Greek territory.” The agreement defined the groups subject to exchange as Muslim and Greek Orthodox. This classification follows the lines drawn by the millet system of the Ottoman Empire. In the absence of rigid national definitions, there was no readily available criteria to yield to an official ordering of identities after centuries long coexistence in a non-national order.[16]

Displacements

The Treaty of Sèvres imposed harsh terms upon Turkey and placed most of Anatolia under Allied and Greek control. Sultan Mehmet VI's acceptance of the treaty angered Turkish nationalists, who established a rival government at Ankara and reorganized Turkish forces with the aim of blocking the implementation of the treaty. By the fall of 1922, the Ankara-based government had secured most of Turkey's borders and replaced the fading Ottoman Sultanate as the dominant governing entity in Anatolia. In light of these events, a peace conference was convened at Lausanne, Switzerland in order to draft a new treaty to replace the Treaty of Sèvres. Invitations to participate in the conference were extended to both the Ankara-based government and the Istanbul-based Ottoman government, but the abolition of the Sultanate by the Ankara-based government on 1 November 1922 and the subsequent departure of Sultan Mehmet VI from Turkey left the Ankara-based government as the sole governing entity in Anatolia. The Ankara-based government, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, moved swiftly to implement its nationalist programme, which did not allow for the presence of significant non-Turkish minorities in Western Anatolia. In one of his first diplomatic acts as the sole governing representative of Turkey, Atatürk negotiated and signed the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" on 30 January 1923 with Eleftherios Venizelos and the government of Greece.[17][18][19] The convention had a retrospective effect for all the population moves which took place since the declaration of the First Balkan War, i.e. 18 October 1912 (article 3).[20]

By the time the Exchange was to take effect, 1 May 1923, most of the pre-war Greek population of Aegean Turkey had already fled. The Exchange involved the remaining Greeks of central Anatolia (both Greek- and Turkish-speaking), Pontus and Kars, a total of roughly 189,916.[1] 354,647 Muslims were involved.[21]

The agreement therefore merely ratified what had already been perpetrated on the Turkish and Greek populations. Of the 1,200,000 Greeks involved in the exchange, only approximately 150,000 were resettled in an orderly fashion. The majority had already fled hastily with the retreating Greek Army following Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War, whereas others fled from the shores of Smyrna.[22][23] The unilateral emigration of the Greek population, already at an advanced stage, was transformed into a population exchange backed by international legal guarantees.[24]

In Greece, it was considered part of the events called the Asia Minor Catastrophe (Greek: Μικρασιατική καταστροφή). Significant refugee displacement and population movements had already occurred following the Balkan Wars, World War I, and the Turkish War of Independence. These included exchanges and expulsion of about 350,000 Muslims (mostly Greek Muslims) from Greece and about 1,200,000 Greeks from Asia Minor, Turkish Eastern Thrace, Trabzon and the Pontic Alps in northeastern Anatolia, and the remaining Caucasus Greeks from the former Russian province of Kars Oblast in the south Caucasus who had not already left the region shortly after the First World War.

The convention affected the populations as follows: almost all Greek Orthodox Christians (Greek- or Turkish-speaking) of Asia Minor including the Greek Orthodox populations from middle Anatolia (Cappadocian Greeks), the Ionia region (e.g. Smyrna, Aivali), the Pontus region (e.g. Trapezunda, Sampsunta), the former Russian Caucasus province of Kars (Kars Oblast), Prusa (Bursa), the Bithynia region (e.g., Nicomedia (İzmit), Chalcedon (Kadıköy), East Thrace, and other regions were either expelled or formally denaturalized from Turkish territory. These numbered about half a million and were added to the Greeks already expelled before the treaty was signed. About 350,000 people were expelled from Greece, predominantly Turkish Muslims, and others including Greek Muslims, Muslim Roma, Pomaks, Cham Albanians, Megleno-Romanians, and the Dönmeh.

By the time the conference in Lausanne took place, the Greek population had already left Anatolia, with an exception of 200,000 Greeks, who stayed after the evacuation of the Greek army from the region.[25] On the other hand, the Muslim population in Greece, not having been involved to the recent Greek-Turkish conflict in Anatolia, was almost intact.[26]

Aftermath

The Turks and other Muslims of Western Thrace were exempted from this transfer as well as the Greeks of Constantinople (Istanbul) and the Aegean Islands of Imbros (Gökçeada) and Tenedos (Bozcaada). In the event, those Greeks who had temporarily fled these regions, particularly Istanbul, before the entrance of the Turkish army were not permitted to return to their homes by Turkey afterwards.

The punitive measures carried out by the Republic of Turkey, such as the 1932 parliamentary law which barred Greek citizens in Turkey from a series of 30 trades and professions from tailor and carpenter to medicine, law, and real estate,[27] correlated with a reduction in the Greek population of Istanbul, as well as that of Imbros and Tenedos.

Most property abandoned by Greeks who were subject to the population exchange were confiscated by the Turkish government by declaring them “abandoned” and therefore state owned.[28] Properties were confiscated arbitrarily by labeling the former owners as “fugitives” under the court of law.[29][30][31] Additionally, real property of many Greeks was declared "unclaimed" and ownership was subsequently assumed by the state.[29] Consequently, the greater part of the Greeks' real property was sold at nominal value by the Turkish government.[29] Sub-committees that operated under the framework of the Committee for Abandoned properties had undertaken the verification of persons to be exchanged in order to continue the task of selling property abandoned.[29]

The Varlık Vergisi capital gains tax imposed in 1942 on wealthy non-Muslims in Turkey also served to reduce the economic potential of ethnic Greek business people in Turkey. Furthermore, violent incidents as the Istanbul Pogrom (1955) directed primarily against the ethnic Greek community, as well as the Armenian and Jewish minority, greatly accelerated emigration of Greeks, reducing the 200,000-strong Greek minority in 1924 to just over 2,500 in 2006.[32] The 1955 Istanbul Pogrom caused most of the Greek inhabitants remaining in Istanbul to flee to Greece.

By contrast the Turkish community of Greece has increased in size to over 140,000.[33]

The population profile of Crete was significantly altered as well. Greek- and Turkish-speaking Muslim inhabitants of Crete (Cretan Turks) moved, principally to the Anatolian coast, but also to Syria, Lebanon and Egypt. Some of these people identify themselves as ethnically Greek to this day. Conversely, Greeks from Asia Minor, principally Smyrna, arrived in Crete bringing in their distinctive dialects, customs and cuisine.

According to Bruce Clark, leaders of both Greece and Turkey, as well as some circles in the international community, saw the resulting ethnic homogenization of their respective states as positive and stabilizing since it helped strengthen the nation-state natures of these two states.[34] Nevertheless, the deportations brought significant challenges: social, such as forcibly being removed from one's place of living, and more practical such as abandoning a well-developed family business. Countries also face other practical challenges: for example, even decades after, one could notice certain hastily developed parts of Athens, residential areas that had been quickly erected on a budget while receiving the fleeing Asia Minor population. To this day, both Greece and Turkey still have properties, and even villages such as Kayaköy, that have been left abandoned since the exchange.

See also

- Great Fire of Smyrna

- Cretan Turks

- Greek Muslims

- Vallaades – Greek-speaking Muslims of Macedonia

- Cappadocian Greeks

- Fridtjof Nansen

- Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

- Greek genocide

- Greek refugees

- Greeks in Turkey

- Pontic Greeks

- Karamanlides

- Caucasus Greeks

- Twice A Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey

- Armenian genocide

References

- 1 2 Matthew J. Gibney, Randall Hansen. (2005). Immigration and Asylum: from 1900 to the Present, Volume 3. ABC-CLIO. p. 377. ISBN 1-57607-796-9.

The total number of Christians who fled to Greece was probably in the region of I.2 million with the main wave occurring in 1922 before the signing of the convention. According to the official records of the Mixed Commission set up to monitor the movements, the "Greeks' who were transferred after 1923 numbered 189,916 and the number of Muslims expelled to Turkey was 355,635 [Ladas I932, 438–439; but using the same source Eddy 1931, 201 states that the post-1923 exchange involved 192,356 Greeks from Turkey and 354,647 Muslims from Greece.

- ↑ Nikolaos Andriotis (2008). Chapter The refugees question in Greece (1821–1930), in "Θέματα Νεοελληνικής Ιστορίας", ΟΕΔΒ ("Topics from Modern Greek History"). 8th edition

- ↑ Howland, Charles P. "Greece and Her Refugees", Foreign Affairs, The Council on Foreign Relations. July, 1926.

- ↑ Ryan Gingeras. (2009). Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the end of the Ottoman Empire, 1912–1923. Oxford Scholarship. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199561520.001.0001.

- 1 2 Ryan Gingeras. (2009). Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the end of the Ottoman Empire, 1912–1923. Oxford Scholarship. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199561520.001.0001.

- ↑ Dawkins, R.M. 1916. Modern Greek in Asia Minor. A study of dialect of Silly, Cappadocia and Pharasa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Karakasidou, Anastasia N. (1997). Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia 1870–1990. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Keyder, Caglar.. (1987). State & Class in Turkey: A Study in Capitalist Development. Verso.

- 1 2 Umut Özsu. Formalizing Displacement: International Law and Population Transfers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- ↑ Mustafa Suphi Erden (2004). The exchange of Greek and Turkish populations in the 1920s and its socio-economic impacts on life in Anatolia. Journal of Crime, Law & Social Change International Law,. pp. 261–282.

- ↑ Naimark, Norman M (2002), Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe, Harvard University Press. p. 47.

- ↑ Dinah, Shelton. Encyclopaedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, p. 303.

- ↑ Dimitri Pentzopoulos (1962). The Balkan Exchange of Minorities and its Impact on Greece. Hurst & Company. pp. 51–110.

- ↑ Yaprak Giirsoy (2008). THE EFFECTS OF THE POPULATION EXCHANGE ON THE GREEK AND TURKISH POLITICAL REGIMES IN THE 1930S. East European Quarterly. pp. 95–122.

- ↑ MUSTAFA SUPHi ERDEN (2004). The exchange of Greek and Turkish populations in the 1920s and its socio-economic impacts on life in Anatolia. Journal of Crime, Law, and Social Change. pp. 261–282.

- 1 2 3 BI ̇RAY KOLLUOG ̆LU. (2013). Excesses of nationalism: Greco-Turkish population exchange. Journal of the Association for the Study of Ethnicity and nationalism. pp. 532–550. doi:10.1111/nana.12028.

- ↑ Gilbar, Gad G. (1997). Population Dilemmas in the Middle East: Essays in Political Demography and Economy. London: F. Cass. ISBN 0-7146-4706-3.

- ↑ Kantowicz, Edward R. (1999). The rage of nations. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans. pp. 190–192. ISBN 0-8028-4455-3.

- ↑ Crossing the Aegean: The Consequences of the 1923 Greek-Turkish Population Exchange (Studies in Forced Migration). Providence: Berghahn Books. 2003. p. 29. ISBN 1-57181-562-7.

- ↑ "Greece and Turkey – Convention concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations and Protocol, signed at Lausanne, January 30, 1923 [1925] LNTSer 14; 32 LNTS 75". worldlii.org.

- ↑ Renée Hirschon. (2003). Crossing the Aegean: an Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey. Berghahn Books. p. 85. ISBN 1-57181-562-7.

- ↑ Sofos, Spyros A.; Özkirimli, Umut (2008). Tormented by History: Nationalism in Greece and Turkey. C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. pp. 116–117. ISBN 1-85065-899-4.

- ↑ Hershlag, Zvi Yehuda (1997). Introduction to the Modern Economic History of the Middle East. Brill Academic Pub. p. 177. ISBN 90-04-06061-8.

- ↑ Yosef Kats (1998). Partner to Partition: the Jewish Agency's Partition Plan in the Mandate Era. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 0-7146-4846-9.

- ↑ Koliopoulos, John S.; Veremis, Thanos M. (2010). Modern Greece a history since 1821. Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 94. ISBN 9781444314830.

- ↑ Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact on Greece ([2. impr.]. ed.). London: Hurst. p. 68. ISBN 9781850657026. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

At the time of the Lausanne Conference, there were still about 200,000 Greeks remaining in Anatolia ; the Moslem population of Greece, not having been subjected to the turmoil of the Asia Minor campaign, was naturally almost intact. These were the people who, properly speaking, had to be exchanged.

- ↑ Vryonis, Speros (2005). The Mechanism of Catastrophe: The Turkish Pogrom of September 6–7, 1955, and the Destruction of the Greek Community of Istanbul. New York: Greekworks.com, Inc. ISBN 0-974-76603-8.

- ↑ Tsouloufis, Angelos (1989). "The exchange of Greek and Turkish populations and the financial estimation of abandoned properties on either side". Enosi Smyrnaion. 1 (100).

- 1 2 3 4 Lekka, Anastasia (Winter 2007). "Legislative Provisions of the Ottoman/Turkish Governments Regarding Minorities and Their Properties". Mediterranean Quarterly. 18 (1): 135–154. doi:10.1215/10474552-2006-038. ISSN 1047-4552.

- ↑ Metin Herer, “Turkey: The Political System Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow,” in Contemporary Turkey: Society, Economy, External Policy, ed. Thanos Veremis and Thanos Dokos (Athens: Papazisi/ELIAMEP, 2002), 17 – 9.

- ↑ Yildirim, Onur (2013). Diplomacy and Displacement: Reconsidering the Turco-Greek Exchange of Populations, 1922–1934. Taylor & Francis. p. 317. ISBN 1136600094.

- ↑ According to the Human Rights Watch the Greek population in Turkey is estimated at 2,500 in 2006. "From 'Denying Human Rights and Ethnic Identity' series of Human Rights Watch" Archived July 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Human Rights Watch, 2 July 2006. Archived July 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ US Department of State – Religious Freedom, Greece http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2006/71383.htm

- ↑ Clark, Bruce (2006). Twice A Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey. Granta. ISBN 1-86207-752-5.

External links

Media related to Population exchange between Greece and Turkey at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Population exchange between Greece and Turkey at Wikimedia Commons Works related to Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations at Wikisource

Works related to Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations at Wikisource- The Exchange of Populations: Greece and Turkey